Interview with Bénédicte Kurzen

Bénédicte Kurzen (1980) is a French freelance photographer working for Noor photo agency. She holds a Master’s degree with Excellence in Contemporary History from the Sorbonne, Paris. She studied Semiology for one year, and wrote her thesis about the Myth of the War Photographer. In 2003, she moved to Israel and took up photography, covering hard news in the Gaza Strip, later working in Iraq, and Lebanon. Encouraged by Stanley Greene to contribute to a Violence Against Women project, Bénédicte changed from news to documentary photography, covering the situation of widows in the Gaza Strip, which was screened in Visa pour l’Image, 2005. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harpers, TIME, The New York Times, Newsweek, Paris Match and Stern among others.

The photographer arrived in Latvia to contribute to project Sea Change, where she photographed youth in Daugavpils. When, after several unsuccessful attempts to meet, we finally met, she came with a tulip in her hand and smiling charmingly. Having a cup of coffee, we discussed cultural differences, advantages and difficulties of a woman in a photojournalist’s work, as well as the stereotypes and prejudices of the profession.

Your previous work has been mostly created in conflict zones in the Middle East and Africa. What did bring you to Latvia?

I’m participating in Sea Change project- a documentary about young Europeans. We are several photographers who are each working in a different country. It’s been a very long process of dismantling because it’s the first time I am working in Europe after 10 years. It was very puzzling. At the first week I didn’t know what I was looking at, nor what I was looking for, but I thought that I should probably do something about the Russian speaking people. The more I was talking to people, the more I understood that it didn’t mean anything. People don’t really care about the division, so why should I? The more I talked to the youth, the more I felt that what mattered was to create a story about the search of the happiness. I found a group of young people in Daugavpils. They are amazing, creative people who work to survive but also have a very rich life outside their jobs. I’m very surprised because in Western Europe we always seek a job that makes us happy and then after work maybe go see an exhibition or a movie. They actually do things – making art, playing music, spending time together in readings, I found it very significant. The youth who are staying in Daugavpils, because lots of them have left, they are in quest of happiness. We had a very simple together being, they didn’t mind me taking the photographs, we went everywhere together and it happened naturally. Now, at the end of my first trip, I don’t think I will keep a lot of the images, because while searching the subject, I’ve been using all kinds of cameras and supports. Also, I’m trying to narrow down the photographic language. Now I have to decide what I really want to show, what I felt when I met young people in Latvia, so I will come back soon. I also had a conversation with one of the project managers the other day and she told me a thought about Latvian reality that interested me – people, who can change Latvia economically, have left the country, but people, who have stayed, are dreamers, artists who love to live here. I think my story will somehow be about this statement – the tension between these two groups of people. I want to understand this micro-drama.

How is it to do something so different?

I’ve been going through lot of changes, starting fresh in Europe. I thought that maybe this project, instead of being very journalistic, could take an angle of a diary how I met all these people – who advised me to meet someone and how it lead to another person – the tree is growing. It’s awkward but at the beginning I didn’t know what I was looking at – there are scenes that you can also find, for example, in a bar in Paris – people with a cool haircut are sitting in cool places, having a coffee but then it’s not the same – people are functioning differently, they are not the same people. It’s very strange to find (and I’m not sure if I have found it) the distance from what I was looking at. Being in Europe is like being in a bubble but there is also a micro bubble in it, so I had an idea of the bigger bubble but I didn’t know what the micro bubble meant.

How did you make the decision to become a photographer?

By pure chance! First important element was the fact that I was a left wing activist. I started to take photos of anti-globalization protests in different places in Europe. Then I got involved in Pro-Palestinian group, so I travelled to the West Bank and Jerusalem to document what was happening there. I wanted to stay two more months there to work on two series – one about unrecognized Bedouin villages and another about the soldiers who were completely psychologically crashed after their military service. The first was a complete failure because I didn’t have any access. And then I fell in love with an Israeli guy which makes you realize that there are also good people on the other side of the fence. Randomly I met a photographer on the streets of Jerusalem whom I had met a year earlier in Perpignan. As I answered what I was doing there, he offered me to collaborate. Then I covered the hard news in the Gaza Strip. I knew in a way that I wanted to become a photographer but I had absolutely no idea how. Things just played for me!

Your thesis was Myth of the War Photographer. What did you discover – what is the myth and what is the truth?

To make it short : war photographers are perceived as modern heroes. I wanted to understand how we build the whole idea of war photographers being heroes and what are the elements of this image that they project. At that time I got really upset with the fact that the war photographer was positioning himself as an ultimate witness. It’s only partly true. It’s brutal and that’s just the way it is. It’s hard to go there and not to feel voyeuristic. It’s part of why we make all the excuses for us being there. Just to be there should be enough! We shouldn’t have to justify ourselves. But we do. And that’s the part I don’t agree with. Also, I think we give too much room for pathos. Don’t tell me that it was terrible, show me the pictures. Pathos is a vicious movement.

I recently read quite an incredible statement that photographer is not a feminine profession. You’re a conflict and war photographer. From your perspective, what are the misconceptions and the reality of a woman photographer?

I was at the ISSP School and one tutor said that the words are more masculine and the images are more feminine because they are more emotional (laughs). You never know what the truth is but it puzzles me. If I go a little bit back in the history, the reality of things is that our profession has followed the evolution of the society, like being a soldier or a policeman. Now we benefit from this change but we forget that the first pictures in the concentration camps were taken by Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White was first war photographer, Gerda Taro was taking pictures of the Spanish Civil war, Catherine Leroy spent years in Vietnam and Françoise de Mulder in Lebanon and there are many others. The only thing I notice as a problem of being a woman and covering all these issues is the fact that at some point, if you really want children, there is a problem. For men, it’s clearly not an issue. From talking to women photographers I know that you have to make a choice. Some of them don’t feel that it’s a choice because they don’t want children. But it bugs me at the moment. It’s the only issue I see. On the contrary, if you’re in the war zone, I don’t think and I don’t see any difference between a female and a male photographer, I believe only in individual sensitivity. I don’t see any justification for a special woman photographer prize, for example. It might have been an encouragement 20 years ago to stimulate woman to do this job but not now, it doesn’t make any sense to be rewarded because you’re a woman.

Isn’t it still a very masculine world?

I don’t really know. Lot of tough war photographers I know are woman. Stephanie Sinclair built her career on that, Véronique de Viguerie picks all the toughest topics on the planet, I’m not sure if it’s a men’s world. The only difficulty is that it is physically challenging and women are more vulnerable. Lara Logan, a CBS reporter was sexually assaulted while covering the celebrations in Tahrir Square following Hosni Mubarak’s resignation. And editors are more concerned if we have all the safety gear with us etc. But I don’t think that there would be the same reaction for a man. Again, I have never experienced that because I’m a freelancer but some friends in Paris who work for newspapers told me that the editors don’t want to send them to a place because it’s too dangerous.

Have you ever felt differently in the field because you’re a woman?

I think it’s actually a great advantage. It has served me because people are less inclined to be scared by a woman in a way. In Africa it really plays for us. Sometimes people don’t take us seriously enough but in other cases it’s an asset.

Are there emotionally low points?

It’s a journey. I’ve been on an amazing journey for 10 years. It’s like a circle, maybe I have the same questions as 10 years ago but I formulate them differently. Importantly, we should never stop questioning what we do and how we do it. If you stop, you’re dead. It’s an issue if an editor wants you to remain in your comfort zone. I want to explore different things, like in Latvia, there is a universe of possibilities. Every story can be told in a different way. I used to be very angry, not giving any care for problems of Europeans, as flu, instead of Africans who lost their children, for instance. But with the years I’ve changed because every worry is a worry of a different degree, depending where you come from and where you live. It’s nobody’s fault but it is like it is. You have to be more flexible. I don’t understand when somebody tells me that my images are “too much to take”; if you don’t relate to the subject, it’s fine but don’t get emotionally involved! Just open your heart and be curious! Not to be interested is one thing but positioning yourself voluntarily on the emotional level, I cannot accept that. Why should anyone be interested in what I feel? First of all, it’s intimate and secondly, how does it relate to the story? What do you think I can feel in front of a dead body? I think the reaction would be the same for everyone. I don’t want anyone to ask me how I felt as a human being but as a photographer. Yes, you have to be angry to be passionate. Photography saved my life – if I don’t care about photography, I don’t care about anything.

Do you have to be politically active?

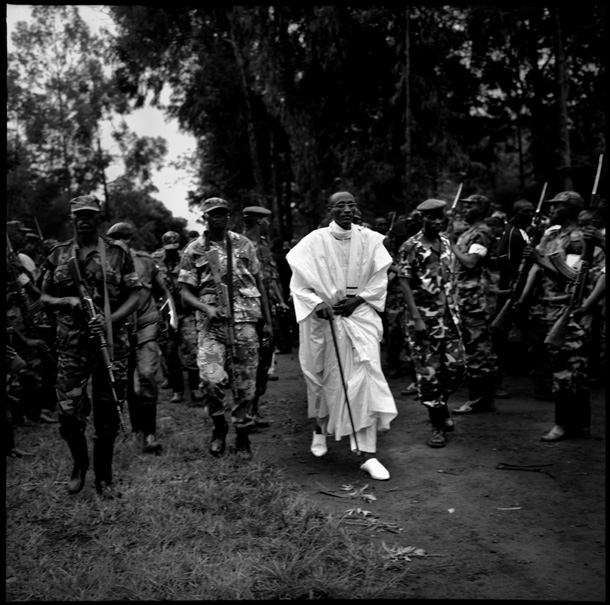

It’s a very difficult question. When you cover a conflict it’s very hard not to take a side. The core of what I do is definitely moved by empathy. If you see so much misery, people dying and suffering, if you’re a human being, unless terribly cynical, your heart goes to them. Conflict always has two sides. Still, the photographers feel the need to show the distress, I think. The whole point of my agency – NOOR – is to put the light on the issues that are not covered. On the other hand, almost the evil side of the things is also interesting because you need to understand it as well. In Congo, it was in a way more interesting to take the pictures of the general Nkunda who was involved in terrible crimes to understand how crazy he was than to join other photographers and take more pictures of the refugees. So yes, to be politically involved comes from the empathy, you develop it with people. Nevertheless, we have to be very careful with emotions because they are shortcutting the thinking. It’s easy to take a picture of a victim but how can you know that the person a week ago wasn’t the killer? It’s not always easy to tell who the victim and who the perpetrator is. A maximum of information is always needed, you cannot be one sided.

Can photography raise the awareness of the issues?

It can but I’m not sure we should highjack with emotions. My aim is to be able to provide a maximum of information, so people can decide for themselves. Once the pictures are out there, they don’t really belong to you anymore. When you take and show a picture, it’s a fact of faith. You need to have a belief from the beginning until the end that you’ve done the right thing and without expecting anything in exchange.

How do you deal with the search of the subject matter when so many photographers are covering the same?

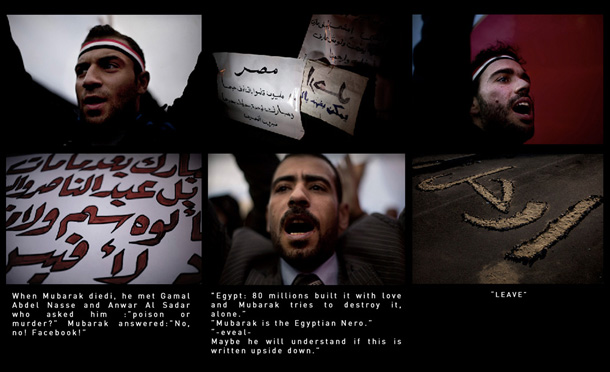

It’s a very big question. When it’s easy to cover, everybody is there! The young people go to get an experience, it’s fine and healthy. The real question I ask myself even a few hours before I jump on the plane is – what am I going to do there? It was a pressing problem in Egypt, for instance. It felt like a photo festival. I wanted to find how the revolution translates differently. Every square centimetre of the Tahrir Square was covered with words. The work I chose to show was a little victory on emergency, on myself, and an homage to the Egyptians who stood.

Who are your mentors and influences in photography?

Good people always meet and exchange a lot. I have a very good feeling of belonging to a family. Stanely Greene gave me the first opportunities. Patrick Chauvel, Kadir van Lohuizen, Jerome Delay – it goes on and on. The experience I have so far, I also like to share it. I remember working in Gaza with Bruno Stevens, it creates bonds.

What are your dreams?

I’m not an ambitious person. I just want to fill my life with joy and love. Love for the people I photograph and for my family.

At the end of the day, what is the biggest reward?

I don’t expect anything, I’m not sitting and waiting for praise but I received an email a few days ago, which sums up what a reward could be. This person wrote that my work moved him and he wanted to share his emotions with me. He said that my images interrogate and lighten. He thanked me for giving those images for others to see. I couldn’t ask for more, it’s beautiful! I’m also happy when my niece asks me what is happening in Nigeria or if my nephew asks me information from one of my stories to use it in his paper in school. It makes me happy if people are curious about what I do. It doesn’t give a meaning to what I do, it’s meaningful just to be there.