Madness as a policy

Photographer, director and photo book author Antoine D’Agata (1961) feels profoundly about the ever more topical dilemma between technicality and spontaneity, manipulation and experience in photography. A member of the well-known Magnum Photos agency who came to Latvia to take part in the Riga Photomonth 2014 photography festival, he sees photography as a platform of personal, political and aesthetic confrontation, in which he has no right or wish to be a protected onlooker and through which he captures institutional and existential violence – prostitutes, drug addicts and migrants.

You’re only 52 but said in an interview that you’re finding it harder to work.

You can see that well yourself (smiles).

You look good.

My body has become weak from the workload, chemicals and stress. And I keep overburdening myself. I just returned from a month long trip along France’s highways, where I shared very personal and intimate experiences with other people. The same drugs and excess are everywhere. The body takes part in it all, but it hurts.

Wouldn’t it be easier to stop using drugs?

To me, drugs are about wanting as much as possible from life. It’s not about wellbeing, women or significance – it’s about exceeding limits, about understanding, about experimenting to the max.

People who have gotten carried away with alcohol and then stopped drinking say they are dizzied by the sudden sense of clarity. Perhaps you’d feel the same way giving up drugs.

My experience comes largely from other people. Meeting these people isn’t easy. I need to find these people and convince them to talk to me, and these are very intimate meetings. Lately, I’ve been working with a girl who’s had incestuous relations with her father. To get close to these people, to lose your mind and allow for these odd and miraculous meetings to occur, you need drugs, alcohol or anything else that lets you connect and forget about limits and morals. I don’t recommend others do it, but it works for me. Using drugs as a means of finding my way to other people has long been my “strategy” – a strange word in this context.

I’m interested in people who are mentally, physically and socially “off the rails”. To get close to these people, you have to trade your common sense and do what these people expect from you. These people trust me and share their reasons for being, their experiences, names and characters. However, they also expect everything in return. You can’t stay safe, asking others to reveal themselves…

But imagine what would happen if you found yourself in a room with one of these people and didn’t use drugs. Wouldn’t you speak to the person?

Of course, I’d talk. But I couldn’t be the friend, the lover, the photographer at the same time… You know, I ask a lot from these contacts. I want everything. I want for those meetings to be complete. I’m neither a journalist, nor a writer, psychologist or painter. I am them all at once. There is a price to pay to get to that level of madness and unconsciousness.

I’m just trying to understand whether you’re trying to find an excuse for your addiction.

(Coughs) No!… Of course, I’m addicted – addicted to excess, to intense sensuality.

A stereotypical Frenchman?

No (laughs), if that were the case, I’d spend more time in France. Of course, drugs have become my lifestyle, a part of my body. After messing around with amphetamines and experimenting with that level of sensuality, you want to take your own life. To get back to life and just feel normal, I have to use morphine or heroin. That’s how you start fooling around and juggling with chemicals and, of course, get pulled into the vicious circle. When I say this method works for me, it means I know how to use these excessive means to reach my goal and continue exploring.

But do you remember everything that happens?

Yes. Hash is the only drug I don’t like because it takes me somewhere but I forget everything. So I don’t use it. I have control over all other drugs.

Seeing heroin users in the streets doesn’t make it seem like a particularly social drug.

Doctors help me deal with the mad lows, and I use the morphine they legally prescribe, as well as heroin to avoid losing my mind. After a crack and crystal meth cycle, the mind no longer follows and it gets really hard.

Do you use mainly amphetamines and crack on your social expeditions?

And cocaine. This is a very detailed interview (laughs).

I just want to understand how these drugs help you.

I have to emphasise that drugs are never the intention.

If your body is addicted then, in a way, drugs are your intention.

Well, I don’t have a home but if I did, I wouldn’t go home after work and relax by getting high. I only use drugs when I need to meet certain people and understand certain things.

So, you’re a social drug user?

It’s never social. It’s always with the aim of getting somewhere.

You don’t use drugs when you’re alone?

I use morphine when I’m alone. I do it every day to stay sane. It’s like medicine.

You don’t drink alcohol?

Very little, only when needed for socialising. I used to use alcohol for many years. I had hepatitis C and my liver is like a large sponge. But I’ve gotten rid of the hepatitis, by using interferon for a year. At that time I couldn’t do anything, I was depressed. Then I seriously cut down on the alcohol. It takes more from me than it gives. I also stopped smoking because nicotine took too much from me and didn’t give anything back. But I haven’t stopped using drugs, that’s a question of strategy.

Does your lifestyle have anything to do with having grown up in Marseille?

Yes, of course, because I grew up in the 1970s when Marseille was getting over the French Connection years (ed. – reference to an American thriller of the same name about Marseille’s drug mafia) when good cheap heroin was everywhere. Even kids from good backgrounds used it. Many people used heroin.

Did you inject it or smoke it?

Yes, I injected it. I started doing it when I was 17. It was the lifestyle in Marseille – a very poor city without any prospects. So, heroin was one of the things kids could do. The city had major unemployment and economic issues, you could only get odd jobs. There were powerful social protests in Marseille and I grew up on the streets with anarchists and a sort of situationist movement. From the very beginning, politics and life on the street went hand in hand for me. And so it remains.

Afterwards, I moved to Bristol where I became a heroin dealer in the squats. I started to travel a lot. I went to Nicaragua and El Salvador where war was raging, and I received drug shipments, got high and reveled with the prostitutes. I wanted to be a part of life on the streets, and Marseille where lifestyle and politics were one was a decisive factor in this decision. Politics not through ideas and the mind but through the lifestyle.

Who were your parents?

Sicilian immigrants.

So you’re Italian?

Sicilian. That would be the same as comparing Latvia to Russia. You shouldn’t confuse them (laughs). My mother comes from a family of Sicilian fishermen. Most of my uncles were fishermen in Marseille but my dad was a butcher and so were his ancestors. My brother is still a butcher. When I was 17, my first job was as a butcher at an abattoir.

Wasn’t it horrible?

Leaving school, it was a good way to enter life. Like a slap in the face. Your day starts with stacks of dead flesh.

Do you eat meat?

Yes, I’m a big meat eater.

So, you didn’t know what to do, if you don’t count enjoying life?

Actually, it wasn’t about enjoying life. Of course, when you watch someone take drugs, the whole thing seems different to what it means for the user. My drug use was largely dictated by my political conscience.

Were you a leftist and an anarchist?

Very extremely so. I was sympathetic to leftist terrorist organisations. It was the late 1970s. Our heroes were Jacques Mesrine – a big French gangster, a police murderer who ended up killed by the police in the streets, German terrorist Andreas Baader and Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols. Different influences, you could say. Those were different times, very different from today.

Do traces of an anti-elitist instinct remain within you?

I don’t try to solve and change anything but, yes, I do choose people, territories and society in which I want to spend my life. Yes, I live in the mountains, yes, I live with drug addicts, prostitutes and criminals. Not because of a political strategy but because these people have nothing, they belong nowhere, they don’t even have the chance to exist, so they have to find other ways of existing and feeling. And this is the question that interests me the most – how does one get as much as possible out of life when one has nothing. You have to create new emotional and social layers. It’s not about pleasure, it’s about a desperate attempt to exist.

Isn’t it a bit superficial to be fascinated by drug addicts and criminals? Other people who don’t live as radically and fit into society are equally unhappy.

Yes, but my criteria is comfort. Of course, people who lead normal lives get depressed, hurt and experience social isolation. I acknowledge their pain but it doesn’t interest me. I’m interested in people who have no safe place, nowhere to hide, nowhere to feel at home, and no way to forget themselves. They are people whose minds and bodies are exposed to life without any protection. Their confrontation with life can be through drugs, sex, illness – HIV, for example. And that’s my material. I’m not speaking about this material in an artistic sense. I only have one life and, of course, I want to gain as much as possible from it – I want to see and feel as much as possible. I want to be alive.

A more humble and outwardly normal life can also conceal existential drama. Is that not like a consumer mentality – live for today, catch the moment, indulge in your senses! Sort of like the ads.

(Laughs) I think that’s a strange way of looking at it. Of course, a person who goes to work every day, watches TV in the evenings and shops at the mall at weekends can have a profound existential experience, but at the end of the day it spawns from frustrations, from obsessing over security, from concealment and suppression. All of these things are contrary to the potential of life. And I know that the people I spend my time with didn’t choose their own lives. Among them are people who were raped as children, left in the streets and otherwise humiliated. For me it’s a choice, to meet these people, however, for them that life is fate.

Of course, if they could escape it, they’d choose the house and the mall. It’s natural. I’m not saying they’re heroes. They’re people who have been excluded from the world’s economy from day one. No one listens to them. They are where they are because they no longer have a choice. I’d even say many of these drug addicts and prostitutes try to save up and live a normal life but when it gets too unbearable, they break loose again. And then I meet them. I meet people who go against the logic of self-defense. Ones who are too insane, too ill, too addicted to whatever is doing them harm. Say prostitutes who sell themselves for drugs and get addicted to work that kills them. That’s when it gets interesting to me.

Does it never occur to you to help these people change their lives?

I have tried to do it but can’t in most cases. I’ve managed to get young girls out of that environment a few times. Occasionally, it has worked. For example, one of the prostitutes married a soldier and is now raising kids. I had to buy her out in Cambodia. But how many times can you do something like that? And who am I to judge these people? I’m not a clergyman and don’t work for an NGO whose job it is to save these people. I think that what I do in my situation makes more sense than trying to save these people.

What do you do?

I go my own way, I go as far as possible and avoid compromise.

In what way does this make sense?

Of course, in the end there isn’t much point to it (laughs). I’m not looking for answers, I’m not trying to create meaning for it. Refusing to give up, stop, and keep trying – now, there is a point to that.

To me, the point is not to succumb to the shivers that can overcome you, and not to build a home, find a nice girl to settle down with and have kids. Not giving up, not ceasing to look around you – that’s the point and it’s also harsh.

You sound like the last French existentialist.

Existentialism, situationism – of course, all those things made me, they are still a part of me but I am nothing. I’d like to be something because being nothing isn’t easy.

Aren’t you flirting with yourself? You’ve made a pretty comfortable life for yourself and have become something – you’re a Magnum photographer, travel the world, mingle with the intelligentsia. You descend to hell when you need to.

That’s your stance. I go to the Magnum offices when I need something. My belonging to Magnum is purely strategic, I use Magnum.

Don’t you need your belonging to Magnum to prove yourself?

No, I need it to give myself as much freedom as possible. Before turning to photography I was a builder and that job was killing me. I use photography, Magnum and my gallery only to take what I want, that is as much money as I need to keep living. I don’t build houses, don’t sell much. I don’t need anything other than enough money to go where I want to go. And I haven’t even reached the stage in which I can live off photography – I still teach.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve had 1200 students because teaching is part of my wandering around. Magnum is more of an ideological than an economic stance because I use it to fight for what I believe in, for what is and isn’t photography in my mind. I don’t earn a living at Magnum, I use my position at Magnum as a weapon in my personal fight for what art and photography should be, in my opinion.

What is art in your opinion?

Let’s talk about photography. In my mind, photography is a unique language. Other forms of art let you go to your studio, you have your vision and you create your piece of art. Photography gets used in a space and time in certain situations. You have to be part of them and you create your art at the same time as you find yourself in a specific situation. The photographer’s position is crucial.

For an entire century, photographers focused on watching – composition, lighting, visualisation. Photography doesn’t revolve around these things for me. Of course, it’s a part of photography but, essentially, photography is an answer to the role you play in the situation you are capturing. Because you are responsible for this situation.

That’s why, for the last 15 years I’ve tried to be a part of my photos and tried to depict my role and responsibility within photography. That’s why I wanted to become a character in my own photos. To me, photography is not visual art, it’s the language of situationism – everything revolves around the position and the situation. The visual part undoubtedly helps me say what I want, but my logic has always been to forge intimate relationships with the world of photography.

Do you go to conflict zones?

That revolves around the same idea. I previously mentioned the odd mix of social awareness and self-destructive instinct. Sometimes, I go to conflict zones because I’ve become too addicted. When I spent a year in Cambodia using drugs, I had to return to reality. Staying there had led me to feeling too comfortable, even though I didn’t do it to become a drug addict. I had to go to war to feel fear, to confront myself with the wish to escape, the pointless violence and corpses, and to wake up in the reality of life.

I went to Tripoli when it fell and spent a month there. Being there I wanted only to escape because I was incredibly scared. I went there without an appointment, I didn’t know how to get there. I’m not a war photographer but I went there because I felt I needed to. You should check out the last book – Antibodies or Anticorps in French.

I occasionally take photos of an economic nature – unemployment, migration. After publishing the book I mentioned I photographed migration – people trying to get from Africa to Europe. I even took photos of architecture – ways in which it depicts violence.

In my mind, there are two kinds of violence – the institutional or political, and economic kind that I don’t like but need to capture in photos so as to understand the world I live in, and the second kind, which is an answer to the first kind of violence. I belong to the second kind – it’s a part of me and my body. It’s street violence – the violence of excess and drugs. So, one is my violence and the other is one I fear and one that fascinates me. When I photograph war, the economy, migration and architecture, I do it remotely, with my mind. The photos are usually sharp, distanced, cold. I don’t try to be a part of them, I only confront the motives and fear them.

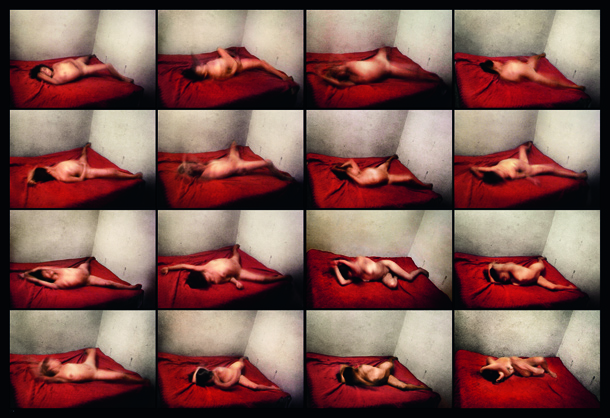

Then there’s the other kind of violence that scares most people but that I am a part of and want to be a part of as much as possible. I don’t want to think, I don’t want to photograph, I don’t want to compose, I don’t want to watch, I just want to be a part of it. It’s a completely different kind of photography. Over the last five years of living in the nocturnal world, I don’t even take the photos anymore. I give my camera to someone else and delve into that world.

Can you be seen in your own photos?

Yes, for the most part you can’t recognise me, but I’m the one using drugs and having sex in most photos. Usually, being in those situations, I don’t really care about the photos. Afterwards, of course, I thoroughly edit and arrange them, try to inject them with meaning because I want them to be coherent. I dispose of a lot of photos and keep the most effective ones. I want good photos, namely, photos that open up mental spaces. After many years of simultaneously taking photos and drugs in the name of forgetting myself, I no longer even want to hold a camera.

Do you trust anyone with your camera?

Yes, the people I meet. Last year, I made a film that will be released soon. Part of it was shown on French TV in December. Most of it was filmed on a tripod. It’s meetings with 12 girls in 12 different countries in which they talk about themselves. Since then I’ve used the tripod a lot in photography as well.

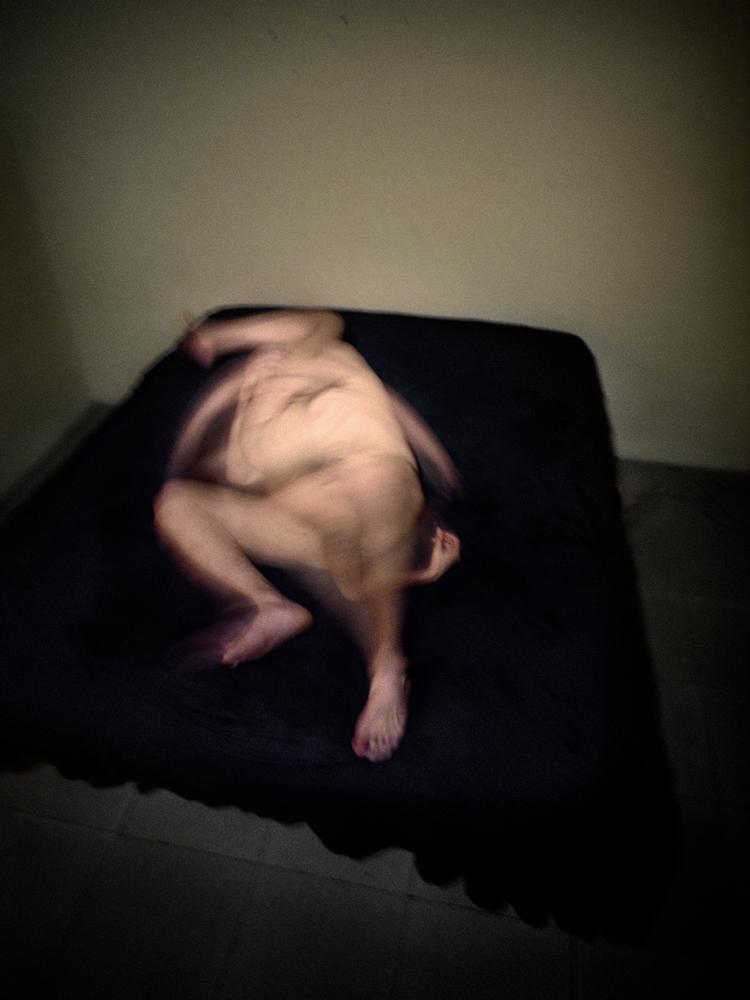

Are your photos blurry to ensure the subjects, you included, a comfort zone of anonymity?

No, blurriness is a method to me. I’ve always used unconsciousness to reveal new characters. I believe in coincidence, I don’t believe in control and the mind. I think photography should be used to depict reality rather than an idea. For many years, blurriness has let me reveal new layers of reality.

You speak of a comfort zone, but that’s exactly what I’m trying to steer clear of. Let’s say everything on the film is completely clear and sharp and touches upon the same themes as the blurry photographs, with the same intensity and relation to life and people. Blurriness is just one way of ensuring it.

Are you a technical photographer? Do you give a lot of thought to the technical quality?

No, I think about how to avoid it. To do that, of course, you have to know the techniques and how to control them. The same applies to lighting – I use as little lighting as possible. My work is as untechnical as possible. I use cameras with automatic settings and a motor. I don’t have control over situations because I’m too involved in them. But to do that, of course, you have to know your camera and techniques. So I can’t say I don’t care about technique – I care about it enough to avoid it.

Do you work with a digital camera?

Yes, for the last two, three years, because I’ve been doing a lot of filming lately and need a camera that can both film and take photos.

Do you know Anders Petersen?

Yes, his works influenced me a lot when I was younger.

He has almost the same approach as you – to get fully involved in the situation.

I’d say he’s different.

What’s the difference?

I think Anders is a wonderful photographer. He IS a photographer. His way is to look at the world and think of a way to look at the world. I’m not a photographer of that level and don’t know if I ever have been, because I think I have different objectives for using photography and my work is to the greatest extent … performance art (laughs)? I don’t know how to call it. My work is largely connected to my life and my actions – I’m more of an activist than a photographer.

You once said in an interview that you share the pain of the subjects in your photos. But you’re in a much more privileged position than they are.

Yes, of course. I’ll never feel what they feel. The biggest difference is that whatever I do and the price I pay for it, be it death, is my choice. I’m not in the same position as a 14-year-old kid who sucks dicks because that’s what life’s thrown his way.

You mentioned kids – there’s a blurry picture in which it looks like a young girl is performing oral sex.

She’s on her knees, she’s not a young girl. She’s 23 years old.

Is that you in the photo?

Yes, it’s me. There’s a certain violence in those pictures. There’s a photo with three women in a bed – some people have said they look like kids. And that’s why these photos were removed from my last exhibition in Paris, because these women looked like kids. There’s beauty in the photo with the three women who look like kids, a beauty that’s part of my world view. You can see violence in these seemingly tiny bodies, all bent over. This violence is part of a sexual act, part of social interaction in these social circles. I want to show this violence.

Quite a few of my photos show girls screaming with their mouths wide open, and you can see the pain. But the pain is never brought on by violence, the pain is brought on by pleasure and is mixed with pleasure. The pain comes from ecstasy, from orgasm. And this pain is important to me – the pain of pleasure. I have to depict this pain, this violence and confrontation that are a part of sex. The pain is always chosen, it’s never forced.

You ask from others to forget themselves but do your job at the same time. Aren’t you taking advantage?

Of course, I go there to do my job and people know that – I lay my cards on the table right away. I can’t say I don’t take advantage of these people because I leave with my photos. These people talk to me, they share their thoughts, they let themselves be photographed and they help me take photos. I pay the price I have to pay. It isn’t always money – people ask to prove respect in other ways, too. Sometimes, I pay money because I want to out of respect. You have to pay people who sell their bodies for money.

I give however much I can afford, irrespective of whether I gain something or not. But there are other ways of demanding respect. For example, if I’m asked to have sex without a condom, I do it. I’m sometimes asked – if you want to share me, then why do you need a condom? That’s the price you sometimes need to pay – to prove the person can trust you.

Do Georges Bataille’s ideas resonate with you?

Yes, very much so. His work resonates profoundly and beautifully. However, his work revolves around fiction and there’s a certain contradiction in that for me. Of course, for Bataille fiction is a way of dealing with his challenges whereas my challenge was to return to reality and see if I could find the same amount of intensity, beauty and insanity in my own experiences, rather than my fantasy world. I love Bataille but, at the same time, he leaves me full of suspicion and I fear him because I don’t want to get lost in a fantasy world, I want to remain in reality. Reality can give me as much as his words have given me. But yes, to this day his words continue to show me the way.

Do you like Michel Houellebecq?

I’ve never read his work. I’ve been told he has a more cynical disposition but perhaps not. But I’ll read something of his.

There’s a certain atmospheric similarity between your work and that of director Gaspard Noé.

Yes, I concede we could share a few common obsessions and interests. We are very different people. We have very different ways of working with things but sometimes we meet and have a drink together.

Considering your fellows are well known personalities in French culture, can we talk of a certain French intellectual disposition?

It may be easier to see from the sidelines. I’ve spent 15 years living outside of France and have never felt like a Frenchman – always a migrant. But, of course, I grew up there as a child and France is part of me. I’ve been most influenced by (Louis-Ferdinand – V.G.) Céline. I had his Journey to the End of the Night in my bag for 12 years.

Did you graduate from high school?

No, I didn’t finish it.

So, how did you get to study with Nan Goldin?

I spent my final year at high school working at an abattoir and completed my high school education later on, at night school. I then spent a month studying sociology at university but understood it wasn’t for me. Since I’d spent a year living in the streets, going to university was too radical for me. I already felt too old. I was Nan Goldin’s student 15 years later at ICP – International Center of Photography in New York. I was already 32 years old then and the studies were more like workshops with photographers and less like university. I then returned to France and worked as a builder by day and a barman by night.

How did you become a photographer for Magnum?

In 1999, I was asked to do an exhibition of my old photos and I organised a small show at a cafe. My works were noticed and they ended up at Christian Caujolle’s VU agency where I spent five years working as a photographer and wrote a few books.

In 2004, I was approached by Magnum and turned them down. When they later wrote to me a second time, I agreed because my relationship with Christian and his agency had become almost family-like and claustrophobic.

Magnum gives you commissions, right?

I’m not shooting anything for them. I’m fighting them. I don’t believe in anything that Magnum stands for today. But I do believe it’s worth fighting for good practice in photography.

What is your disagreement with Magnum?

Currently, Magnum deals in advertising and corporate work. Magnum has been conquered by money. But I adore Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa and the whole Magnum tradition!

Speaking of family – do you have one?

I have four daughters from three different women. I don’t live with any of them. It’s been eight years since I’ve had a home, I live in hotels. I don’t often meet the kids but try as often as I can and endeavour to cultivate close family ties between them.

They are close. For example, one of my daughters is currently spending two months with her half-sisters even though the mother refuses to see me. I always try to visit them when I’m in France and occasionally take them on holiday in winter.

Do your daughters know about your working process?

They know what’s inside me. With the exception of the very youngest one, who’s too small. They dont want to know more, and they avoid this side of me. They do not accept what I do, but I think they understand why I am doing it – that is, trying to find my way to be human – and that it is important to me. Of course, I have lost a lot of time I could have spent with them, a lot of common experiences, but they know that I’m doing my own thing, and they know that I’m trying to be a good person. We are very close to each other, and they usually poke some fun at me for what I do.

Have you ever wanted to protect the people you meet, to intervene in someone’s life?

No, never. With the exception of war, of course, in which everything becomes useless, and you just want to stop the world. In my “nocturnal work”, I only document my own journey. Of course, sometimes I do reportage work. For example, in Cambodia, I was travelling with NGOs, tracking pedophiles and shooting them as they approach children. But the people from the organizations stopped them, not me, I was just a witness. Being a witness is not my usual way of working – my usual way of working is to be an actor in own life. Yes, sometimes there is a context of existential violence in my work – AIDS patients, prostitutes, who have no choice. You cannot change anything, because it’s too late. I try to get as close to these people as possible. In this context, my most recent film, Atlas, is very important. All the girls talk about AIDS, about themselves and about me, our relationship, my desires, and sometimes they are angry at me and complain that I want everything. The only thing I can give these people is respect – to be close to them, listen to them, look at them, make love to them. No one wants to be close to some of these girls and make love to them, because they are too sick. If taking responsibility means seeing all people as equal and being with them, I take responsibility. But to change their lives? No, I cannot. I cannot even change my own life – I am addicted to drugs and I have made my choices. My current official girlfriend is a porn actress. Most of my girlfriends are prostitutes and go out every night, because I do not support them financially – relationships cannot be based on money. I’m not a jealous man, but when they walk the streets, I go crazy with jealousy. Sometimes we look at scenes from my girlfriend’s movies together. That’s what I call responsibility – to love someone, even if she has sucked the dicks of a hundred other men. My moral is – never get too comfortable, never protect yourself, never avoid pain – always confront the intensity and pain. I’m no great lover of life.

Your have the nonconformist attitude of a young rebel. Over time, most people surrender to the temptation of a more normal life. Don’t you ever become bored?

Yes, most people surrender, but not me. I can’t be nonconformist and surrender to a normal life at the same time. I am a very privileged person. I go into to people’s lives, they give me everything. How could I get bored? Creating a new life is not an option – life is absurd. Of course, I also do perfectly normal things – go fishing with my lover, go for a walk with her through the woods, or look at the cherry trees blossoming in spring. My photos show only one aspect – the carnal side of life. That is, I’m trying to reflect a certain essence of human existence, in which meaning arises from the flesh. In general, I experiment with different experiences. Sometimes people ask me why I only show the dark side, why I don’t show the good side of my relationships. This is because my goal is not to document my life, it is to let my own fear and anger be expressed and find a visual form. And that does not include eating breakfast with a nice girl. It involves a process in which human flesh and screams become something transformative.

So your work is based on fear?

Sure. But many believe that I take pleasure in my work and crave sex. I’m not more sexual than anyone else. I use sex because it is an area with a lot of options. It is an area that is open to fragility, and there’s a lot of fear, and I can confront my own fears. I chose this area because it is what I fear most. I’m afraid of sex, death, and intensity. When I the fear stops, I stop taking photos. For example, now I’m working with HIV positive girls, because I had to push the borders again. I don’t know what will happen tomorrow. I work with fear itself, surrendering to my own fear.

Were your children’s mothers prostitutes?

No, but two of them were drug addicts, who I photographed. But they are good mothers – I think I have an instinct for that.

So you are somewhat familiar with security.

I do not support misery, drug abuse or violence – it all saddens me. But I have to be a part of it. It’s a long story. You should ask your online magazine to order my latest book Antibodies – there are 30 pages of text in quite a good English translation, which explains my opinion much better than this conversation.

How do you find the characters in your photographs?

I usually know straight away. I look for the most extreme people. The ones who are beyond caring, beyond normality. When I enter a bar, it only takes me a second to see the people I’m interested in. Of course, not all of them want to talk to me.

In your artistic explorations, have you ever attracted the attention of the police, or on the contrary, criminals?

Yes, of course, many times. Sometimes I pose as a reporter to get into certain places. But people recognize me as an addict within seconds. There have been police raids that I have run away from and hid. I regularly have to hide from the police in a number of countries, because I’m associated with the wrong people and the wrong places. I have been in hospital several times, after being beaten up for my camera, or because someone didn’t like the way I talked. But I’m not really scared, because whatever happens to me, it will never get as bad as for the people I meet.

What is taboo to you?

Many things. For example, to perform a violent act on anyone who does not desire it. Violence may also be a part of sex, and in my opinion that is not harmful violence. But a single slap to anyone who does not want it is wrong. Pedophilia is also taboo. I do not give money to street children, because I think it just perpetuates the vicious circle of misery. I don’t use money as a form of payment, but I do give as much as I can to mothers and other people who really need it.

Do your parents know how you work?

The father is dead. My mother is 75 years old and regularly admonishes me not to sleep with just anyone. For a long time, it was very hard for them to accept what I do. Since the age of 17, we had a somewhat bitter relationship. Our relationship is a long story. As we all grew older, it became easier to accept each other. My mother now says that I have helped her understand something about life. Of course, we still disagree on many issues.

Your desire to look the truth in the eye and share the pain of others seems almost like an ascetic Christian viewpoint.

No, I am a strict atheist, but with a very strong religious past. Even at the age of 14, I wanted to become a priest. I went to a preparatory course for priests. I was very involved in religion.

How did you start to rebel against religion?

It happened when I read (Jean Paul) Sartre, (Albert) Camus and (Mikhail) Bakunin. At the same time, I couldn’t reconcile my teenage sexual urges with the moral standards of the Catholic Church. I was also very interested in the criticism of the extreme left, and so in six months I went from an apprentice priest to a punk.

Were you captivated by the ideas of communism?

In my teenage years, when I was reading Sartre’s Nausea, I realized it was not about communism, but about how you feel when you look at a glass of water, when you touch a wall, when you look at flesh. It is about life and the question of what life is. Life revolves around a godless world and unanswerable questions – not Stalinism and communism. Of course, the avoidance of comfort and the need to confront myself with life has roots in some long-ago influences. But I have seen to much shit, violence and pain to believe in any god. If god exists, he is a crazy bastard.