The Family of Man: The Photography Exhibition that Everybody Loves to Hate

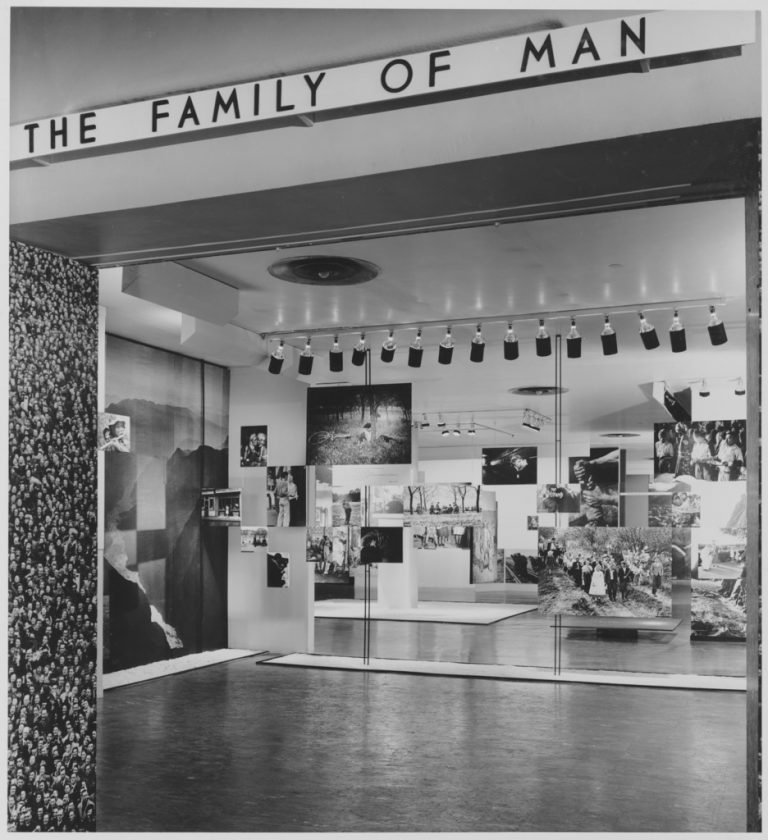

“The greatest photographic exhibition of all time – 503 pictures from 68 countries – created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art,” says the cover of the photobook accompanying the exhibition The Family of Man. 1)Edward Steichen, The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time: 503 Pictures from 68 Countries (New York Museum of Modern Art, 1955). The exhibition took place at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, from January 24 to May 8, 1955. It was highly popular – the press claimed that more than a quarter of a million people saw it in New York. But it gained its central role in the history of twentieth century photography largely because of its international exposure. The U.S. Information Agency popularized The Family of Man as an achievement of American culture by presenting ten different versions of the show in 91 cities in 38 countries between 1955 and 1962, seen by an estimated nine million people But, contrary to its popular reception, scholarly criticism of the exhibition was – and continues to be – scathing.

What was The Family of Man?

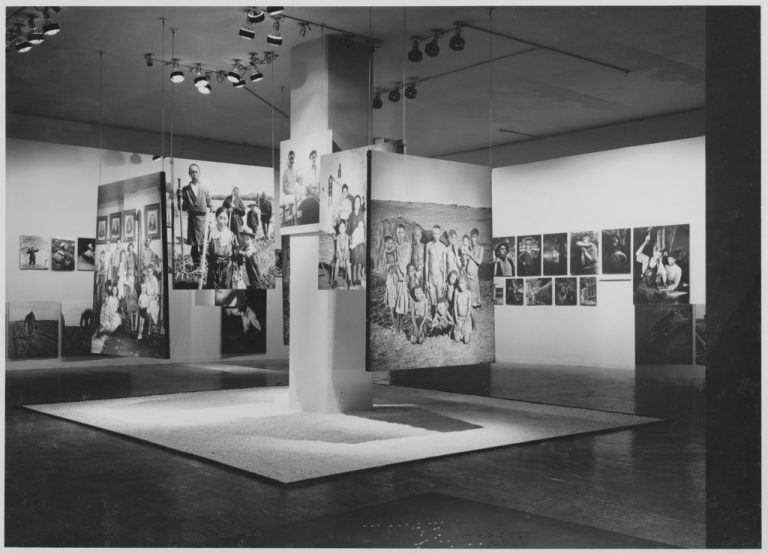

The images featured in the show were taken mostly from the Life magazine archive, a few also from other leading magazines of the time such as Vogue or Ladies Home Journal. Photography agencies such as Magnum, Black Star, and Rapho Guillumette were also a significant source of images. The exhibition was curated by Edward Steichen, assisted by Wayne Miller, and designed by architect Paul Rudolph. The images – mostly contemporary documentary photographs – were grouped in thirty-seven thematic sections that narrated a generalized story of human life. A pivotal point in the exhibition was a large, backlit color transparency in a darkened room with red walls depicting the explosion of a hydrogen bomb. It was followed by a huge photomural depicting the assembly hall of the United Nations, which was supposed to symbolize a better future than a nuclear war. The exhibition ended with a group of images showing happy children, displayed in a room with pink-colored walls. As naive, sentimental, or melodramatic as it might have been, the exhibition at MoMA adequately expressed the hopes and dreams of many.

But The Family of Man was much more than the sum of all the images it featured. It offered an unusual visual experience. Made-to-order enlargements of various sizes were arranged as if on a magazine page, contrasting large images with smaller ones. The spatial arrangement of the exhibition added a distinct architectural aspect. The different sizes of the prints provided a dynamic rhythm of distinct emphases and background. The unframed prints were mounted directly on panels, some of which were free-standing and removed from the wall, some others – hanging from the ceiling or arranged on a circular platform. These panels extended into the viewers’ space and created a visually interesting landscape that visitors were invited to explore. Their progress through the exhibition was limited to the route planned by the organizers because the panels were arranged in a maze-like way that guided visitors through the thematic sections from the entrance to the exit.

The scholarly reception of The Family of Man is greatly influenced by Roland Barthes who in 1957 criticized the exhibition for an essentialist depiction of human experiences such as birth, death, and work, and the removal of any historical specificity from this depiction. 2)Roland Barthes, “The Great Family of Man,” in Mythologies, transl. by Annette Lavers (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972), 100-102. Later, Allan Sekula viewed the exhibition as a populist ethnographic archive and “the epitome of American cold war liberalism” that “universalizes the bourgeois nuclear family” and therefore serves as an instrument of cultural colonialism. 3)Allan Sekula, “The Traffic in Photographs,” Art Journal 41, no. 1 (1981), 15-25. Christopher Phillips, on the other hand, criticized Steichen for silencing the voice of individual photographers by decontextualizing their photographs and imposing his own narrative. 4)Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (1982), 27-63.

Since the late 1990s, however, new and more nuanced readings of The Family of Man have emerged. Lili Corbus Bezner’s analysis of individual images included in the show reveals the heterogeneous visual content that was forced to fit into the framework of the populist surface and Steichen’s overarching narrative. 5)Lili Corbus Bezner, “Subtle Subterfuge: The Flawed Nobility of Edward Steichen’s Family of Man,” in Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 121–174. Ariella Azoulay has argued that the exhibition can be viewed a visual equivalent to the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. 6)Ariella Azoulay, “The Family of Man: A Visual Universal Declaration of Human Rights” in Thomas Keenan and Tirdad Zolghadr, eds., The Human Snapshot (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 19–48. New articles and book chapters are published on a regular basis. The approach that is the least exploited so far involves focusing our attention on individual images from the show and trying to figure out what they can tell us about the power relations in postwar photography.

Outsider Perspective

Although the prints in The Family of Man were not meant to be looked at as individual art works, they were still meant to be looked at. When audiences encountered the exhibition, not all viewers were pleased all the time. Some of the images turned out to be controversial and outraged some visitors. These cases reveal the chasm between the curator’s worldview and numerous other perspectives coming from cultures different than the U.S.

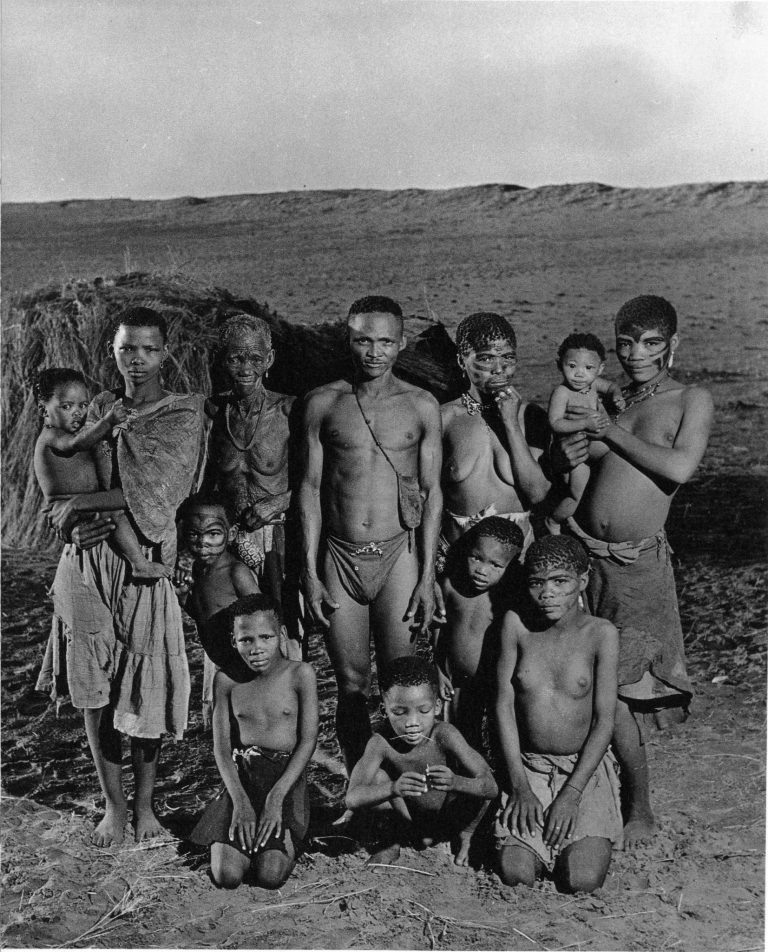

One instance of violent public outrage took place at the Moscow instalment of The Family of Man in 1959. Theophilus Neokonkwo from Nigeria slashed and tore down prints by Polish-born American Life photographer Nat Farbman (1907–1988), taken in Bechuanaland (then a U.K. protectorate, since 1966 the Republic of Botswana). 7)Louis Kaplan, American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 76. The sources do not specify exactly which prints were slashed by Theophilus Neokonkwo. The Family of Man featured five images by Nat Farbman from Bechuanaland. They appeared in different sections of the exhibition.

Reproduced in Edward Steichen, The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time: 503 Pictures from 68 Countries (New York Museum of Modern Art, 1955), 58.

Neokonkwo protested against the way in which the exhibition, according to his statement, depicted all non-Europeans, and especially Africans, “either half clothed or naked” and as “social inferiors” – as victims of illness, poverty, and despair, while white Americans and Europeans were represented mostly “in dignified cultural states – wealthy, healthy and wise.” 8)Theophilus Neokonkwo’s statement appeared in Afro-American (Washington, DC), August 22, 1959. Quoted from: Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 155. This action was an attempt to critique the Western photojournalists’ tendency to exoticize all non-Western cultures – they were outsiders who visited for a short time and with the task of bringing back reportages as shocking as possible. Neokonkwo’s protest was an attempt to point to the power inequality that permitted the global circulation of images made by outsiders such as Farbman and his Life colleagues, but never provided equal space for photographs made by the insiders of non-Western cultures.

One might ask – but were there any? Why don’t we know about them? Paraphrasing the title of the seminal article by second-wave feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, one might ask – Why have there been no famous non-Western photographers in the 1950s? 9)Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” ARTnews (January 1971), available at http://www.artnews.com/2015/05/30/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists/ There is no doubt that talented and skillful photographers lived and worked in many countries across the world. Among the reasons we do not know that much about their lives and work is that they never had such powerful employers as Life magazine and such mighty promoters as The Family of Man, whose world tour was backed by the U.S. government. The cultural clout, money, and professional development opportunities of a Life photojournalist who was carrying a U.S. passport in the 1950s could not be compared with the resources available to his fellow photographers from Bechuanaland, Nigeria, or many other countries.

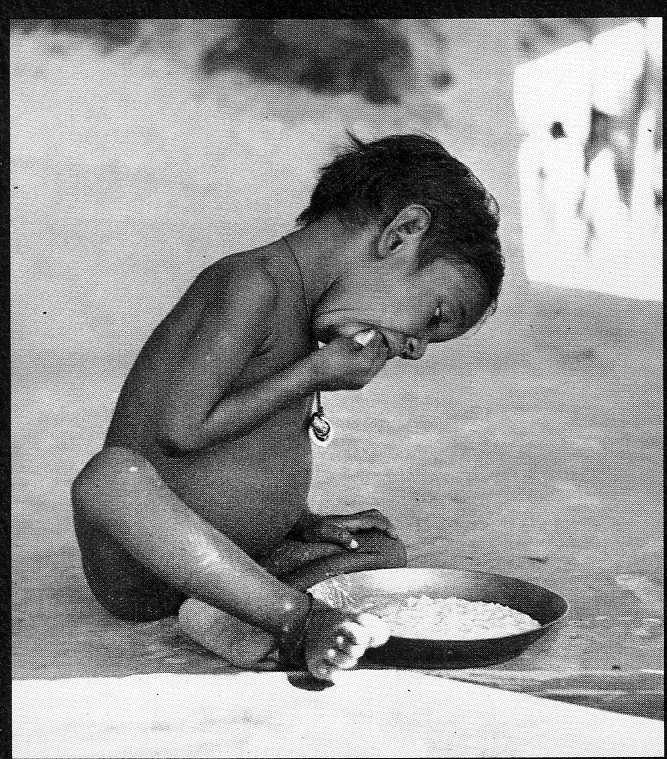

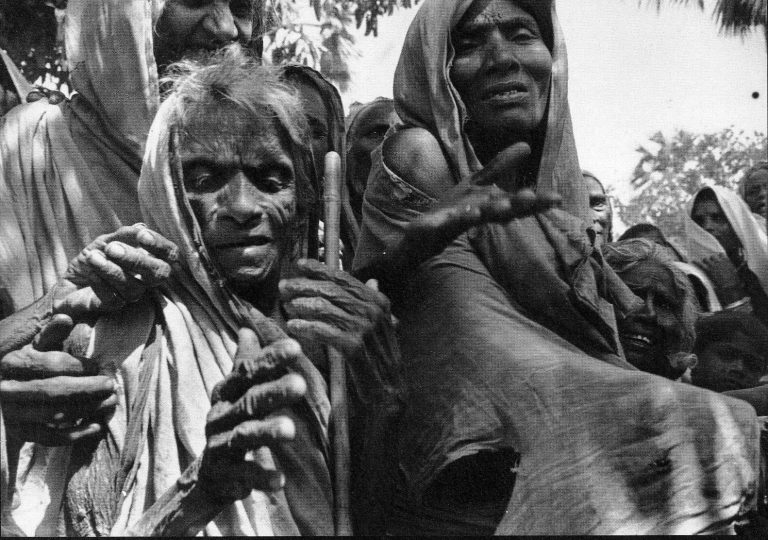

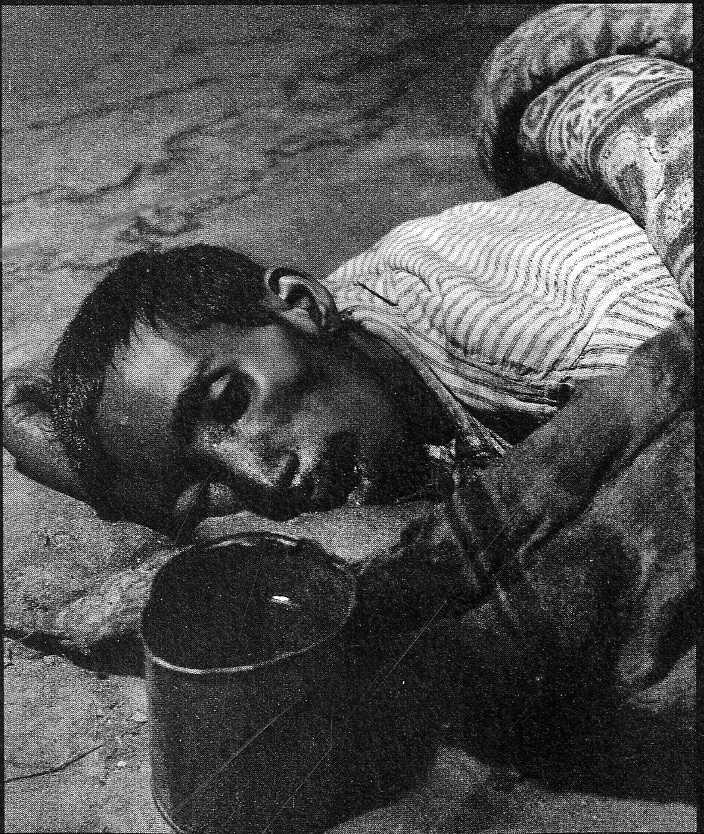

For example, in The Family of Man, thirteen images depict India. Out of these thirteen, seven images explicitly focus on the suffering, the starving, the insane, the sick, and the dying. These images belong to the sensationalist shock-journalism of the human crisis that the illustrated magazines proliferated. A naked baby whose stomach is bloated from malnutrition sits on the floor and eagerly eats rice in an image by American photographer William Vandivert (1912–1989) working for Life magazine. A group of elderly, starving, and desperately, dramatically grimacing women wrapped in rags are observed in close-up in an image by Magnum member, Swiss photographer Werner Bischof (1916–1954). An emaciated, apparently severely ill or dying man with an empty stare and open mouth is laying on the ground in an image by Russia-born American photographer Constantin Joffé (1910–1992) working for Vogue magazine.

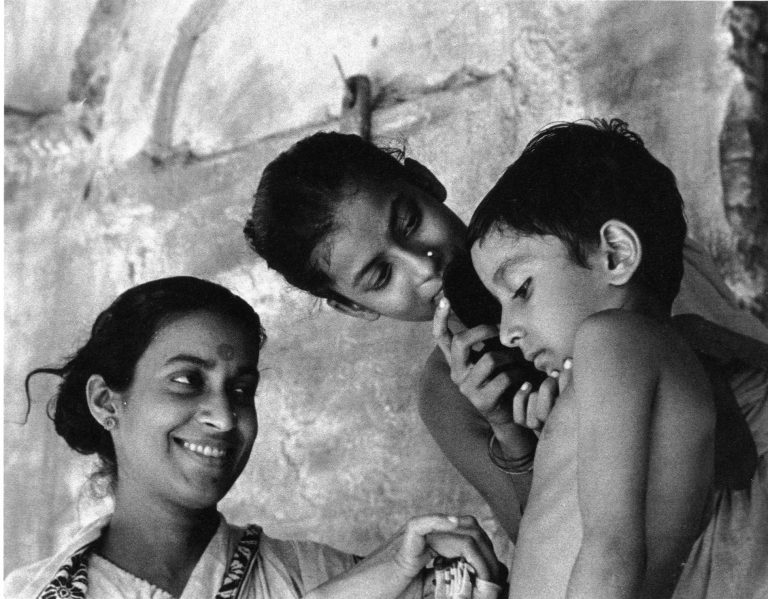

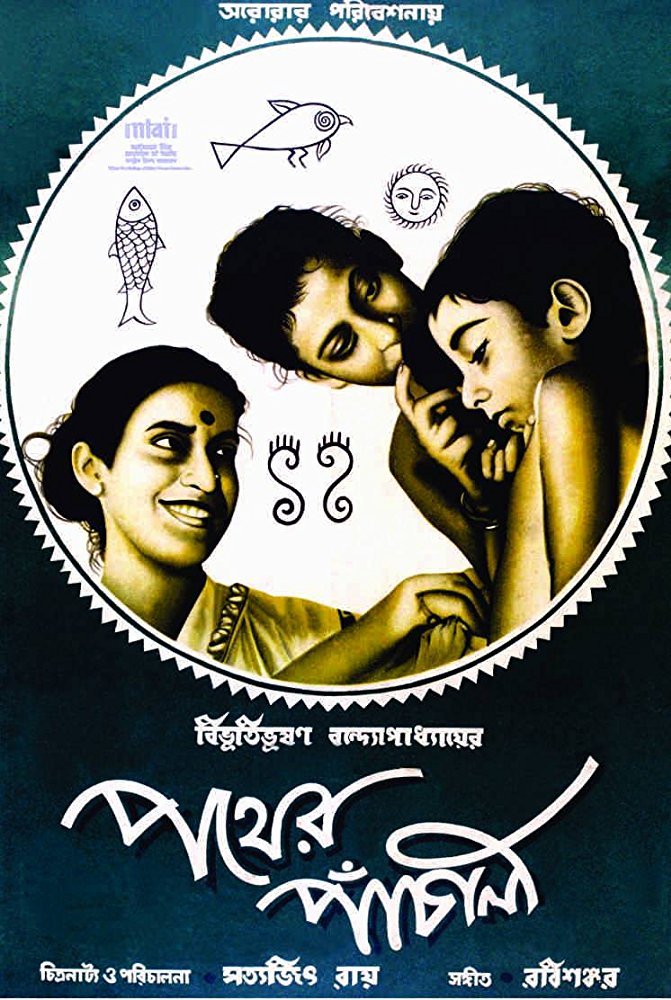

Out of the thirteen images depicting India in The Family of Man, only one was made by an Indian photographer – it is an image attributed to the film director Satyajit Ray (1921–1992) showing seemingly healthy and well-off children. Unlike the majority of images in the exhibition, however, this image is not a documentary reportage, but a film still. The still is from Ray’s first and internationally highly acclaimed film Pather Panchali (1955). Because Ray was not known to be a photographer, and a designated photographer’s name does not appear in the film’s crew list, it is reasonable to assume that the author of this photograph was the film’s cinematographer, Subrata Mitra (1931–2001). 10)“Pather Panchali,” International Movie Data Base, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0048473/fullcredits?ref_=ttfc_ql_1, accessed November 17, 2017. This image was also used in one version of the film’s promotional poster. The inclusion of an image by a local, non-Western photographer in The Family of Man was a rare exception. Out of 256 individually credited photographers whose work was used in the exhibition, only twelve (or 4.6%) represented non-Western cultures: eight from Japan, two from China, one from India, and one – from Pakistan. 11)This estimate is based on the image captions in the book: Edward Steichen, The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time: 503 Pictures from 68 Countries (New York Museum of Modern Art, 1955). But the fact that a still from an Indian film appeared in The Family of Man alongside predominantly documentary, photojournalistic work, is a telling sign of the exhibition organizers’ superficial approach to non-Western material. The attribution of this film still to the film’s director demonstrates that the process of making The Family of Man did not respect individual photographers and their work, especially if it was the work of non-Western photographers.

Insider Perspective

Around the time of the world tour of The Family of Man, however, there was at least one organized attempt to bring to light work made by a more inclusive transnational group of photographers. It was the FIAP Biennial – an international exhibition of creative photography of an unprecedented scope at the time. The biennial, established in 1950, was conceived as a world survey of contemporary photographic art, displaying an equal number of works from each participating country. By 1955, FIAP represented photographers from thirty-six countries throughout the world: eighteen countries in Western Europe, eight countries in Latin America, five in Eastern Europe, four in Asia, one in Africa, and Australia. 12)The FIAP Biennial was the idealistic project of the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l’art photographique, FIAP). This organization was founded in Switzerland in 1950 with an aim to unite the world’s national associations of photographers. FIAP continues to exist to the present day. This article, however, refers only to the work of FIAP during the 1950s and does not consider the later developments in the organization’s history and its changing role throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Even with the best intentions, the Western photographers at times reproduced the worst cultural stereotypes of the colonial era. Meanwhile, Indian photographers who participated in FIAP aimed at creating a more positive view of their country. They tried to communicate that their country was not only impoverished, suffering, tumultuous, bizarre, cruel, “exotic,” “surrealistic” or whatever other adjectives Western journalists ascribed to it, but also a place where regular, dignified everyday life went on and where many people lived peacefully according to their religious beliefs and cultural traditions. When these Indian photographers presented their work in international forums, they wanted to tell different stories about life in independent India than those non-Indian photographers who traveled the world and produced images of “exotic” locations for consumption in Western European and U.S. illustrated magazines.

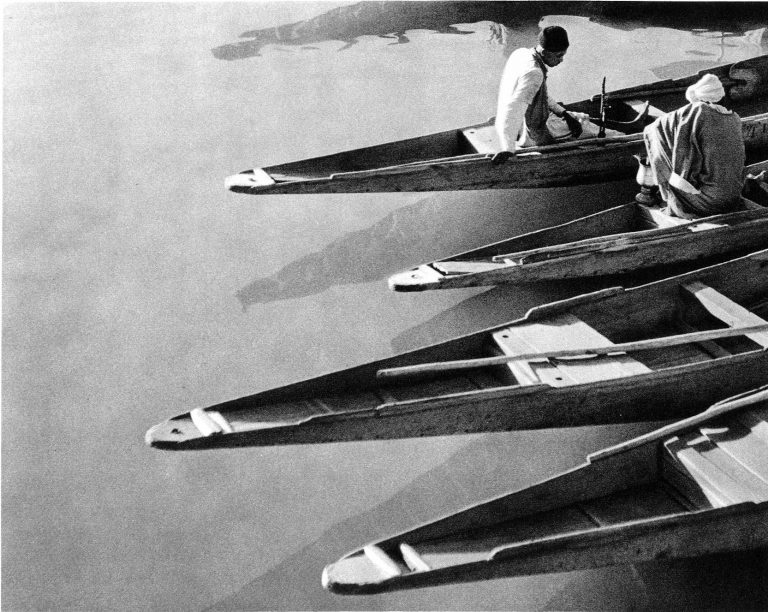

For example, in an image by Indian photographer K. L. Kothary, No Work, included in the 1958 FIAP Biennial, the frame includes the ends of four narrow boats, cutting them off on the left. The viewpoint is from above, and the frame is filled with an even surface of water. The horizon line or any other signifiers of the location of the scene are not visible. Two male figures occupy the two boats farthest away from the camera. One man has turned his back while the other is seen in profile. Their body language suggests that they may be engaged in a conversation with each other. The title suggests an awareness of the social circumstances they share. Yet the source of their unemployment is not specified – the viewers do not learn if the men have no work because the fishing season is over or has not started, or because of other, unknown reasons. Whether the two figures on their boats are fully employed or not, does not influence the perception of the image. Its main content is the rhythm of geometric shapes and an exploration of the flatness effect of the photographic image.

Another example is Music by Indian photographer Vidyavrata (1920–1999), included in the 1962 FIAP Biennial. Besides being a depiction of everyday life in a school, Music is a sophisticated study of photographic composition. From an elevated and quite distant viewpoint, the camera is looking down toward a row of ten children wearing white tank-top shirts and shorts. The children are aligned along a circle drawn on the floor. Inside the circle, there are nine empty chairs. Outside the circle, in the upper left corner of the frame, an adult oversees the proceeding of what likely is to be a game of musical chairs, a common gym activity in schools. The source of light is outside the frame, coming from the upper-left corner and positioned extremely low, suggesting either early morning or late evening light. The main visual feature of this image is the elongated shadows cast by the children that stretch diagonally to the lower-right corner. The dark shadows create a strong diagonal that intersects with the narrow white lines on the ground. Although children at play is one of the typical tropes of postwar humanist photography, here the author avoids superficial sentiment by keeping the children, the location, and circumstances of their play anonymous. Vidyavrata turns a potentially humanist subject matter into an exercise in modernist aesthetics. The compositional arrangement of bodies in space, distinct geometrical shapes and lines – not the children who are playing a game – become the main elements of the work.

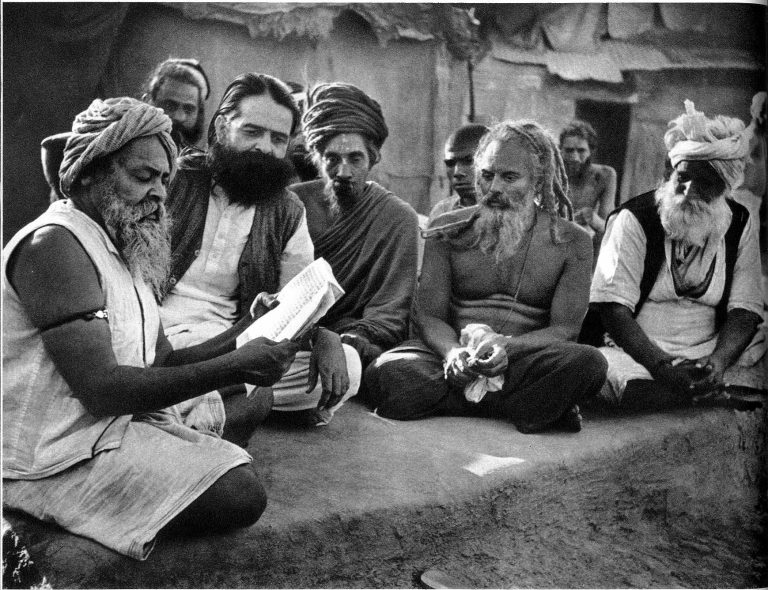

Another example is Listening to the Scriptures by Shreedam Bhatt (life dates unknown), a photographer from the Ahmedabad area. This image, featured in the 1958 FIAP Biennial, captures a group of bearded men sitting on the ground and attentively looking at another man on the left side of the frame who appears to be reading from a book. The group of men takes up most of the frame, and the photograph does not provide much detail to describe the location more specifically apart from a fragment of a low, makeshift rural building in the background. The men sit on top of a special platform in the center of a village – this kind of elevated seating was used for religious holidays, reading ordinances, and funerals. The situation may be part of a funeral ritual or a public reading of an ordinance. The image depicts the life of ordinary people as observed in their natural settings and in an un-posed manner. The photograph is taken at the eye level of the sitting men, thus positioning the viewer among them. This is a very intimate insight into the life of a small village deep in the countryside, which, likely, would not be so easily available for traveling Western photographers – and they would not be interested in capturing a scene of everyday life without any “exotic” practices going on and without anybody visibly sick, starving, or dying.

Through their choice of photographic form – thoughtful compositions, careful arrangement of figures, mastery of unusually positioned light sources and capturing of shadows – Indian photographers attempted to communicate some of their ideals about an independent India in a visual language that they hoped would be understood and appreciated by their peers across the world. Their images attempted to position normalcy and everydayness against Western exoticization and the reporters’ interest in finding chaos, poverty, famine, illness, and misery. Indian photographers responded to the negative cultural stereotypes nurtured by exhibitions such as The Family of Man. Their images attempted to communicate that India was more than starving babies and the dying poor. But, of course, their story is not the one that has so far been central to the history of photography.

The FIAP Biennial and The Family of Man shared a global ambition and aim to represent the world through photography. However, the ways in which both exhibitions envisioned such representation were quite different. The Family of Man demonstrated how the world looked like through the eyes of – mostly – U.S.-based professional photojournalists who traveled to all corners of the globe. The FIAP Biennials, meanwhile, demonstrated how the world looked like through the eyes of photographers who actually lived and worked in all corners of the world. The Family of Man offered a uniform outsider perspective of a vast range of cultures and nations, while the FIAP Biennials provided a vast range of insider perspectives coming from within these cultures. FIAP’s idealistic attempt to give voice to the world’s photographers eventually went unnoticed, largely because of lacking funding and support from the narrow elite of Western European and U.S. professionals.

Epilogue

The Family of Man has a unique place in the history of photography. Most other exhibitions that have made their mark in history are avant-garde, innovative explorations – such as, for example, Pressa (Cologne, 1928), Film und Foto (Stuttgart, 1929), New Documents (New York, 1967), or New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape (Rochester, 1975). Scholars constantly look back at these exhibitions, review and revise their interpretations, and always try to find new reasons for their importance. The Family of Man, however, was never an avant-garde or even particularly innovative exhibition. Its general message – that all people are similar in their joys, pain, and work – was not especially thought-provoking, unexpected, or radical. Its design was attractive, but by no means ground-breaking. Scholars constantly look back at it, but they are on a mission to find new faults and shortcomings. And it seems that The Family of Man keeps providing endless reasons to hate it, despite those few historians who have attempted to analyze the show in a more benevolent light. There is no other single exhibition in history of photography that has been able to irritate several generations of historians. And we are not done yet.

___

This article has been made possible by a support from the US Embassy in Latvia

| 1. | ↑ | Edward Steichen, The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time: 503 Pictures from 68 Countries (New York Museum of Modern Art, 1955). |

| 2. | ↑ | Roland Barthes, “The Great Family of Man,” in Mythologies, transl. by Annette Lavers (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972), 100-102. |

| 3. | ↑ | Allan Sekula, “The Traffic in Photographs,” Art Journal 41, no. 1 (1981), 15-25. |

| 4. | ↑ | Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (1982), 27-63. |

| 5. | ↑ | Lili Corbus Bezner, “Subtle Subterfuge: The Flawed Nobility of Edward Steichen’s Family of Man,” in Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 121–174. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ariella Azoulay, “The Family of Man: A Visual Universal Declaration of Human Rights” in Thomas Keenan and Tirdad Zolghadr, eds., The Human Snapshot (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 19–48. |

| 7. | ↑ | Louis Kaplan, American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 76. The sources do not specify exactly which prints were slashed by Theophilus Neokonkwo. The Family of Man featured five images by Nat Farbman from Bechuanaland. They appeared in different sections of the exhibition. |

| 8. | ↑ | Theophilus Neokonkwo’s statement appeared in Afro-American (Washington, DC), August 22, 1959. Quoted from: Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 155. |

| 9. | ↑ | Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” ARTnews (January 1971), available at http://www.artnews.com/2015/05/30/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists/ |

| 10. | ↑ | “Pather Panchali,” International Movie Data Base, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0048473/fullcredits?ref_=ttfc_ql_1, accessed November 17, 2017. |

| 11. | ↑ | This estimate is based on the image captions in the book: Edward Steichen, The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time: 503 Pictures from 68 Countries (New York Museum of Modern Art, 1955). |

| 12. | ↑ | The FIAP Biennial was the idealistic project of the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l’art photographique, FIAP). This organization was founded in Switzerland in 1950 with an aim to unite the world’s national associations of photographers. FIAP continues to exist to the present day. This article, however, refers only to the work of FIAP during the 1950s and does not consider the later developments in the organization’s history and its changing role throughout the second half of the twentieth century. |