The subjective documentality of Egons Spuris

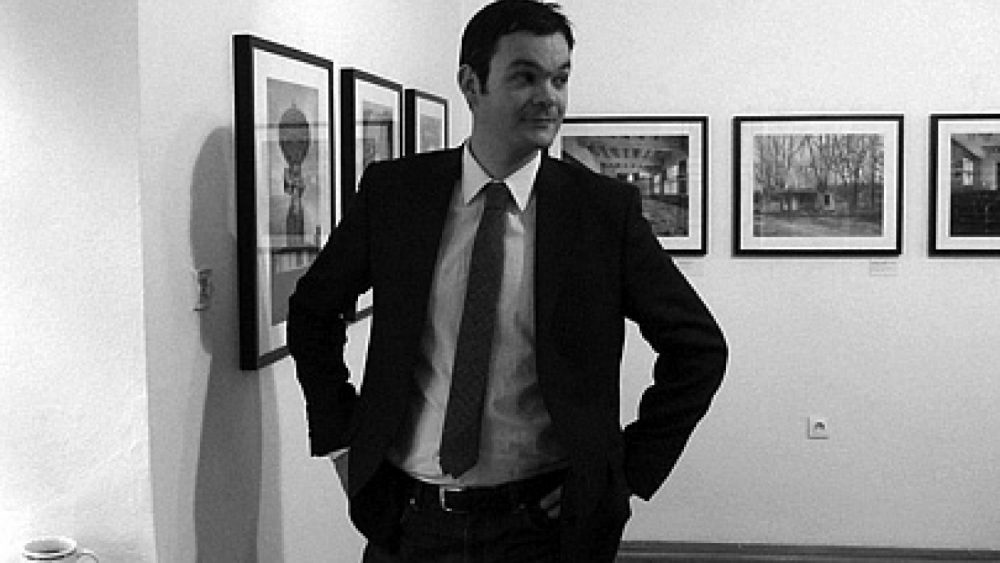

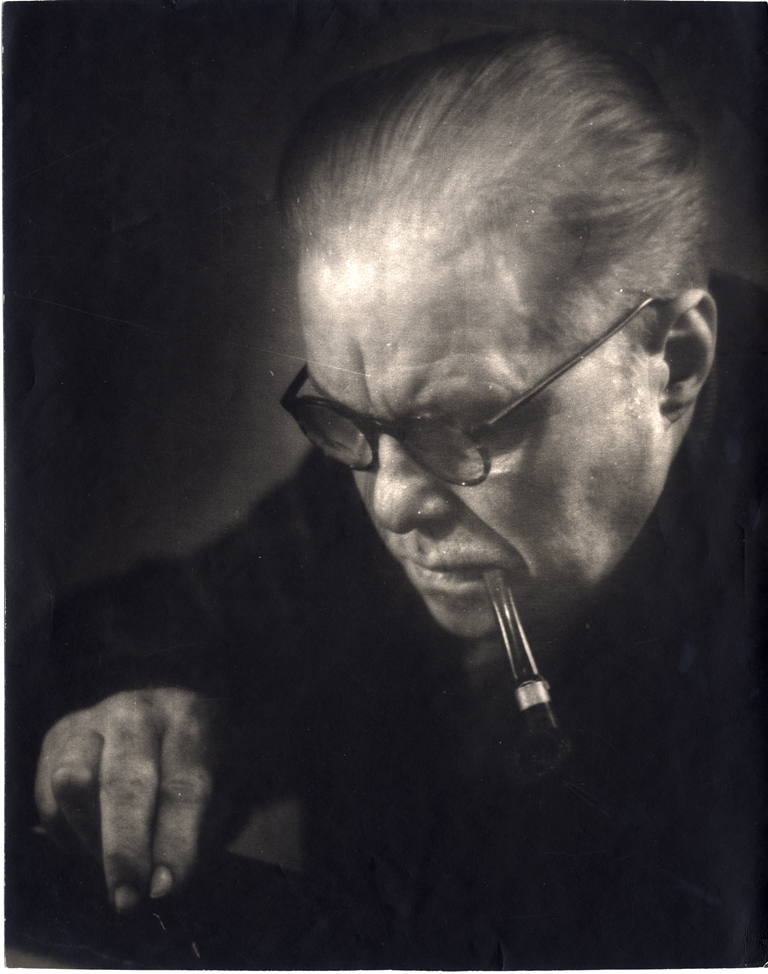

Egons Spuris (1931 – 1990) to my generation is a legend. He is a photographer we did not know because we were too young, but whose artistic contribution, as well as meaningfulness of his oeuvre can be read in his photographs and heard from his contemporaries. Yet, any photographer from the middle-aged and older generation and anybody related to photography bears some memories, opinion or experience in connection with Spuris, his work and teaching approach. The photographer’s son Egīls Spuris summarizes his father’s personality in his photographs: “His greys are warm, but the tonality of black is very vivid. As any part of this environment where a loving human soul grows and lives. And that’s exactly how my father was.”

During the photographer’s lifetime his photographs were exhibited in more than 350 shows in 48 countries. However, today nearly ten years have passed since the last exhibition of Egons Spuris has been organised and a photo album published in Latvia. Both an exhibition and an album were the formats were photographs with Riga’s portrayal were exhibited also by Spuris’ spouse and also a photographer Inta Ruka.

This spring will bring three exciting news in relation to Spuris in the photography world of Riga. There will come out a monograph issued by the publishing house Neputns and compiled by Spuris’ life-long colleague, student and friend Andrejs Grants. There are also two shows being held revealing the photographer’s oeuvre in around 400 photographs: A Place Perfect for Looking at the exhibition hall Arsenal at the Latvian National Museum of Art and Bremen at the Goethe Institute.

Egons Spuris turned to photography at the end of the 1950-ies. In 1962 the photographer graduated from the Riga Institute of Polytechnics with a diploma in radio engineering. On the same year photo club Riga was founded and Egons Spuris became one of the first members. However, starting from 1975, Spuris put all his efforts in the development of photo club Ogre, eventually becoming its Art Director. Before Spuris took over the management of photo club Ogre, he passed the knowledge of his profession to his son Egīls. He remembers that his father simply gave him a piece of equipment – an exponometer – telling this and that about the buttons. He knew the basics, because when living and growing together with his father it was impossible not to learn at least part of it. Later, when looking what came out of these first steps, father told what the mistakes were and how to avoid them. He was not very keen to praise, but by saying “good”, Egīls really knew that it was meant that way. “He let me move on my own, and later followed the same methodological approach when working with his students in Ogre photo club. He did not object against a different kind of thinking and spoke of the mistakes as something that could be corrected. After his critics no one was overwhelmed by the feeling of a loser. On the contrary – it was clear in which direction to go and what to do,” remembers Egīls.

Spuris’ successor and the current head of the club Vitauts Mihalovskis admits that the changes in the club can be explained with Spuris’ understanding that the genre of salon photography popular at the time formed only a tiny part of photography. He was also one of the few who supported the creative work of the alternative movement Fotogrupa A, where among others Andrejs Grants, Valts Kleins and Gvido Kajons were active members. “When Andrejs Grants, Inta Ruka and Mārtiņš Zelmenis joined photo club Ogre, it generally affected the visual language of other members of the club, too. We also had an opportunity to receive more accurate information on photography. Meetings with the muscovite Alexander Slusarev, who always visited Ogre club when coming to Riga, were inspirational, too” tells Mihalovskis. Club members often visited other photographers and they were visited by photographers, art theoreticians, historians and other people from creative circles. “It certainly affected the club’s choice to follow the documentary photography or, in Egons’ words speaking, the creative document,” adds Mihalovskis. Club member Ēriks Drubiņš wrote at the time: “These changes can be spotted in the fifth review exhibition of the club, when our works differed from others with a compact, purposeful artistic handwriting. It was laconism, simplicity and easiness combined with a drive to plasticity, directness of thought and clarity.”

Mihalovskis also admits that it was not an easy task to take over the club after Spuris. The encouragement came from the contemporaries Andrejs Grants and Inta Ruka, because Mihalovskis was a colleague who “grew up” among them. There were also difficulties due to the period of the National Awakening, many members took part in different type of activities. Mihalovskis tries to keep alive the traditions founded by Egons Spuris: “Mostly I want the club to be a place where the young photographers could study and exchange experience on photography. We have thematic shows, personal reviews, meetings with creative people on our schedule. One of the traditions that was introduced by Egons Spuris was the discussions and evaluations of works by other colleagues. Constructive critics is really necessary and valuable.” The fact that Egons Spuris could criticise weaker work so that the author would not take it personally and would get a stimulus to work on, is also approved by photographer Māra Brašmane, who claims Spuris was the biggest authority among the young photographers.

The methodological style and creative success of Egons Spuris were undeniably related to his personal traits. Vitauts Mihalovskis emphasizes his feeling of tact: “It seems, he often struggled to find the right words and action not to offend the author, however, he was consistent in his beliefs. He strongly stood on his feet against all kinds of unfair manipulations that happened in Latvian photography at the time. Egons Spuris was helpful and friendly with anyone whose intentions were honest and open. It seems, it was even difficult to be next to people who were the opposite,” a similar opinion is expressed by son Egīls, saying that tactfulness was one of the main traits of his father’s personality: “He was a man of senses, with a deep inner world. By feeling himself, he felt others,” adds Egīls Spuris. Curator Irēna Bužinska collaborated with Egons Spuris, when he worked at the Latvian National Museum of Art making photo reproductions of the artworks. The curator remembers him as the most polite and sensitive photographer she has ever met; he always took into account the needs of other people he worked with.

Irēna Bužinska admits that the first intention to organize an exhibition was already in 2009, when the non-material heritage of Egons Spuris – a series of photographs titled “Riga in Proletarian suburbs at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century” – was included in the cultural canon of Latvia. Spuris is the only photographer in this canon. Bužinska adds that this fact touched Spuris’ spouse Inta Ruka, and she donated part of the photographs to the Art Museum. Bužinska claims that the contribution served as an impulse for compiling more extensive photo collection and for adding photography to the Museum’s collection.

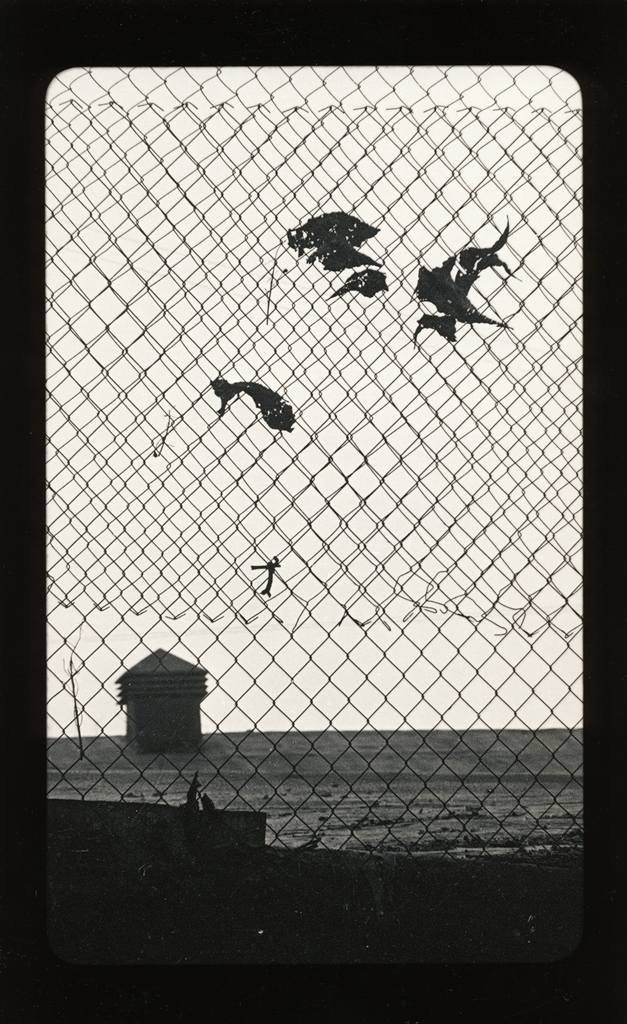

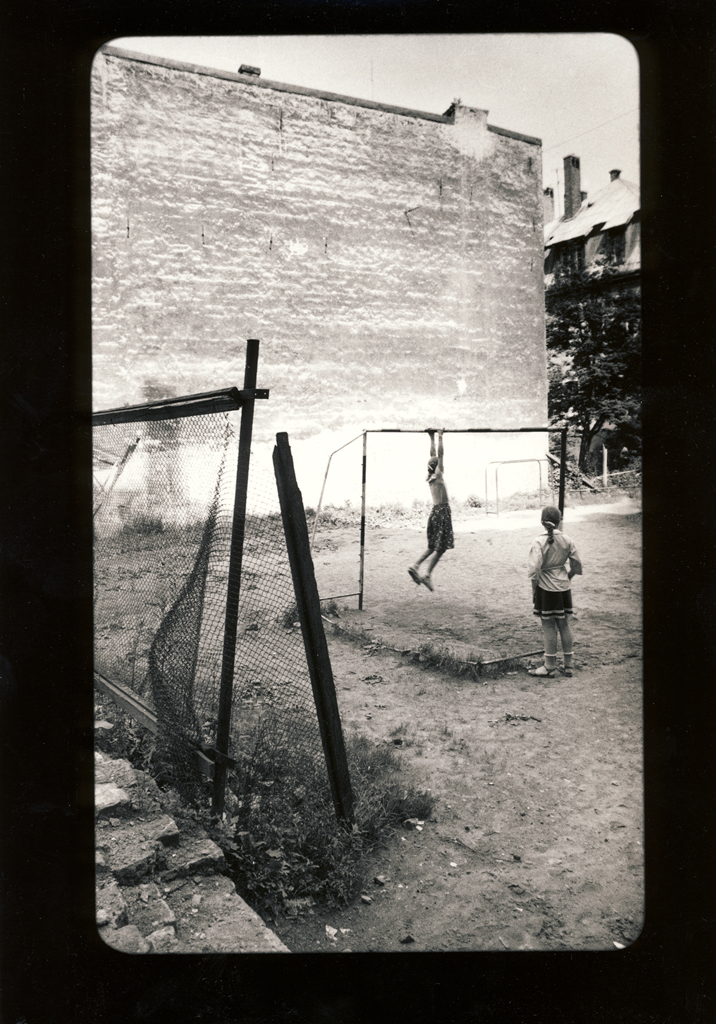

The exhibition at Arsenal is arranged so that the donated collection could be presented, as well as the less known part of the photographer’s oeuvre – not only the most essential and popular works. It was not easy to make such a selection. When organising any exhibition, the curator asks what it is that must be shown from the artist. Traditionally these are the best, the most popular works. In this way Spuris made his selections, and expressed the opinion that if anything was remembered from his art, it would be the photographs from the Proletarian suburb (now called Vidzemes suburb) of Riga. “I think, there were more dimensions to Spuris’ art, therefore a greater scope of works are included in the exhibition, although not everyone finds this choice agreeable. Spuris in his suburban series would not be the same, if he had not taken photographs in the 1960-ies, although critics define them as salon photographs,” explains the curator. She decided to present the creative scope of Egons Spuris, when an artist is looking for a means to express himself, as well as is experimenting with various techniques till eventually he reaches the benchmark which today is known as a canon or a brand. “Such a brand is demonstrated by Andrejs Grants in his newly compiled book. It serves as a foundation for the ideal and polished view. Yet, I am bored by such shows, because I want to learn something new. This exhibition will reveal the less popular aspects of his works, too,” adds Bužinska, noting that organising exhibitions is a creative process, too.

Furthermore, the Goethe Institute will exhibit Spuris’ works in a satellite show Bremen. These photographs were made in 1981, when Spuris, “a photographer with a totally unstained reputation”, visited Riga’s commonwealth city. In his short visit, the photographer managed to produce his own view of the city, “without touristic places, popular objects, but which is nevertheless emotional, vivid and nostalgic Bremen and it will be interesting to compare it with Riga,” tells the curator, who was interested in Spuris’ quest for the image of Bremen.

In order to understand the growth of the photographer and evaluation of his own work, contact sheets will also be exhibited in the exhibitions. Son Egīls remembers the creative process when both went out to take photographs. Egons was deep in his world of feelings and associations, Egīls, in his turn, was looking for interesting moments and angles. “We did not speak about it, but it seems, he already saw the result when only taking a picture. It was a bit adjusted in the copying process. Later it was interesting to compare what was the result of, for instance, a backyard in his interpretation and mine,” adds Egīls. Father was keen to give films and photo paper to the son. He could also choose any camera from the available ones. Father also helped to select the works to exhibit in shows. During university Egīls was not active in photography, but now, after a break of thirty years, Egīls takes photographs again. “He would have liked it!” comments Egīls.

I asked Irēna Bužinska how she came up with the idea for the title of the exhibition A Place Perfect for Looking and what it really means. She explains: “The place is Riga; it is a place where he was born and where he took photographs. It is a place where Spuris learnt to look in his childhood and later had personal and philosophical contemplations on this aesthetically not very pleasing environment, on what he felt and saw here, which at the same time is also a symbol of Riga. Spuris did it in a vigorous and fresh way.” Egīls Spuris also explains the characteristic traits of his father’s works: “Any of his photos can be copied as a passionless documentary photograph, where the author is only looking and documenting a fact. In fact, he has not got such works at all. What is it that he shows in his works? Not the external world, but what he feels inside. And there is a lot to that! If we speak about the suburban cycle, it is the environment where he was born, where he grew up and where he spent all his life. And he experienced this environment in all possible ways! There is a saying that “real men” do not expose their world to others. I doubt that he would speak of it loudly, but his works reveal it all.”

To conclude with, the publishing house Neputns is about to issue a monograph on Egons Spuris and his oeuvre. Andrejs Grants, a photographer and a contemporary of Egons Spuris, compiled the book saying that a serious monograph of Egons Spuris has not been published so far. Yet, he is one of the most prominent Latvian photographers, who took decisions not typical for his time and who developed a photo tradition leaving certain values for his followers, too. The authors of the texts in the book are Eduards Kļaviņš and Pamela Brown, and they put Spuris’ works in the context of that time, culture and photography in the world. “My intention was to produce the image part relatively unrelated to the textual part. I wanted to show, what Egons started with, how he took photographs accordingly to the context of his time, how gradually it took the shape of minimalism and how he started to photograph the suburbs. A certain kind of contribution to the aesthetics of the time was the least I wanted to achieve. For me, it was more important to demonstrate what strong photography is. The readers will be able to notice these changes – how the subjects of his works, aesthetics of shots, perspectives, tonality and contrast change in Egons’ works, starting with his first works and ending with the suburban cycle, totally covering nearly 15 years of work,” comments Andrejs Grants on the principles of selection. He admits that the main thing that Spuris has taught is the possibility to look in a different direction. “Egons was a very talented man, and it created some kind of centrifugal force around him which affected the others, too. In groups you often had to comply with the rules set by the state of affairs, yet he was strong enough not to do it and at the same time a creative personality, who inspired and with whom it was easy to communicate,” Grants explains the attraction that made many photographers head to Ogre. Andrejs Grants also adds that Egons Spuris can be characterised in one word “perfectionist”, because that’s exactly what his attitude for work was. In a way, Spuris can be compared to Salinger’s character, who polished his shoes when going to be broadcasted on television, though he was fully aware that only his torso would be seen by the spectators.