Interview with Hans van der Meer

Dutch photographer Hans van der Meer (1955) offers his reminiscences on Hungary where he spent several years photographing the local life. He tells about his interest in football and how the professional football has essentially damaged the perception of both the game and the image and explains why he is interested in immortalizing his own country and themes that otherwise are left without any notice.

Hans van der Meer has received the World Press Photo award, has published nearly a dozen of books and gives lectures on photography on a regular basis. He has also been one of the project leaders at the ISSP documentary photography project Middle Town: Picturing the Unspectacular.

How did your interest in photography start?

I’m 57 years old, it goes way back (laughs). I didn’t finish my secondary school. I was about 16 or 17 and completed a technical school instead. I bought my first camera, a Zenit. Over the next 6 years I had different jobs but in 1976 I started to work in a photo store, selling cameras and so on. We also did product photography with a friend. The field work I did, I kept it for myself but I quite often went to the photography museum and library of Leiden, I started to get interested in photography that records things. The photographers at that time were influenced by French generation, like, Henri Cartier-Bresson and others.

Street photography was meaningful for me, but it took me years to take a decision, so in 1983 I started to work on projects. I started to attend a post-academic institution and in the second year I went to Hungary. I was already 29 but it was the first time when I really started to do a big project seriously. I had this at the back of my head for a long time, I had hesitation moments but then this coincidence of going to Hungary emerged. I had a short stay in Hungary in 1982, and I really liked Budapest, even with its light absorbing houses. I was fascinated and went to our Ministry of Culture to ask for support. It was still the period of the Iron Curtain. They had an agreement that every year a certain number of Hungarians could come to the Netherlands and vice versa. That year, already eight Hungarians had come to the Netherlands but only one Dutchman had gone to Hungary. The idea was that the number would be equal. So, I was welcomed to go. I went there with an intention to work on a longer project, to discover Hungarian photography scene of the time and also to visit, as I only knew Budapest. My guide there became my best friend. The people were friendly and helpful, I was driven around in a car. I had a young woman next to me who was interpreting, I was introduced to a lot of people and it was overall an amazing experience.

I had a flat in Budapest, I didn’t have much money but I had my Leica and my books. It was an interesting time – I had a whole city in front of me but the people were struggling. I had a romantic period. The series won the World Press Photo prize in 1987, in a daily life category but the local people were mostly shocked about the imagery of their lives I showed during the exhibition in 1986. They didn’t think that a foreigner would show anything else than nice pictures. I liked their Eastern kind of black humor in their images, a way of dealing with their situation. It’s not as much as the photographer thinks that he is photographing, it’s actually next to it or behind it where the story is. That’s what I used later in my other stories, too. I would give a place to the background. My pictures are a lot about the body language, the gestures and the movement. After the book was published, I was more considered a street photographer which I didn’t want to be. So, I started doing other projects, as the one about the factories.

These street views, the manual labor theme, amateur footballers, then the daily life… I see certain romantic features in the subject choice…

It could be! There is definitely something, if not romanticized then surely left open, for instance, the sense of humor. I try to get away from the events that are in the news. It’s more interesting for me to look at the matters where we, in a certain way, fail. Like in amateur football, it’s a very good example – people have a dream, they do it, but it in no way looks like a professional football situation. It’s very touching – to have a dream. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always function in reality. But playing literally means it – we’re pretending!

Football, I guess, is one of the games where the theater is particularly well executed.

Yes, you sometimes want to call 911 when you see the exaggerated reactions of the players! They can lie down as if were shut by a gun! I know by experience, when you have a really serious injury, you don’t move so much but they want to attract the attention. I’m too old to play but when the ball comes to you, you just can’t resist!

How much your fascination with football is about the game, how much is it about something else?

The funny thing is that I tried to photograph football even before I went to Hungry but I couldn’t find the solution for it. It was only in 1995 when I had my 6×9 camera and a newspaper invited me to do an article on football. Suddenly a lot of things came together – I had a chance to be generous, I could play my foreground-background game. In the 1980s, I made a book about archival football photographs. I learnt for the first time what space in the old football photos was left, so you wouldn’t only see the telephoto lens angle that doesn’t actually tell you anything about the game. Before the television, the football photographs were published to understand the game, nowadays it’s about particular persons and not about the information. It doesn’t make sense. It’s a result of the football industry, they want to create and sell heroes. Drama in football is not the close-up but the situation. The space is part of the fun. With the television, the photographers prefer a dramatic face expression to the moment of relations, these images can’t be taken seriously in terms of a story telling, it’s just an illustration next to the text. It almost seems that the photographers don’t believe in the power of photography! It’s a very poor level of communication because football and photography can be a very beautiful combination.

Which you are a proof of!

I had fun being an amateur player and also to talk about this game in a different way. This is what you can still see here, in the villages – you find a football ground, and sometimes there is not even a full team to play the game but they do. It’s a culture but what we usually see, is only the top of the pyramid – the professional part which actually comes from very long tradition of leagues and competitions. When I started my “European Fields” series, I was looking for the situations as far as possible away from the Champions League. A flat area is basically everything you need to play; a human being in the landscape – that’s what I was looking for. The funny thing is that the players don’t differ so much, the passion for football is what they share. They all change to kids when the ball comes near. So do I!

You have made most of the projects in your home country, whereas many photographers go for the stories abroad. How easy is it to photograph your own country?

I have done projects elsewhere but it’s definitely true that I like to talk about my country, my culture. The further you go away, the less you know about the place. I feel probably not very comfortable staying away for too long, unless it is a very particular project to work on, as I went to the US to photograph cowboys. I have been invited to photograph in other countries a lot, like football in South Africa or in South America but I didn’t want to do those projects. It’s so easy to start talking about poor and rich in Africa and the other thing – I wanted to leave that opportunity for African photographers to do it. Why should always Europeans or Americans go there? Let them show their country themselves! It’s not my cup of tea!

In Hungry I felt at home, I was married to a Hungarian woman. But I’m a late father, I have two little girls, so after 2006 I have worked a lot nearby. I can travel but I’m a person who wants to stay there to learn more about the place. I make money with documentary photography but I round it up with some editorial, commercial things, some teaching. It’s just enough to make a living, I’m not rich but I’m not poor either. I have to be more aware now since I have a family. I’m lucky to have been noticed by people because I principally don’t like promoting. Martin Parr came to my house not only to buy but also, as he said, to make me better known. My ambition is not to reach a very wide audience, my ambition is more to proceed with my style. As you said, I tend to feel more comfortable in some situations where I know what I talk about.

Have you made any revealing discoveries about your own country?

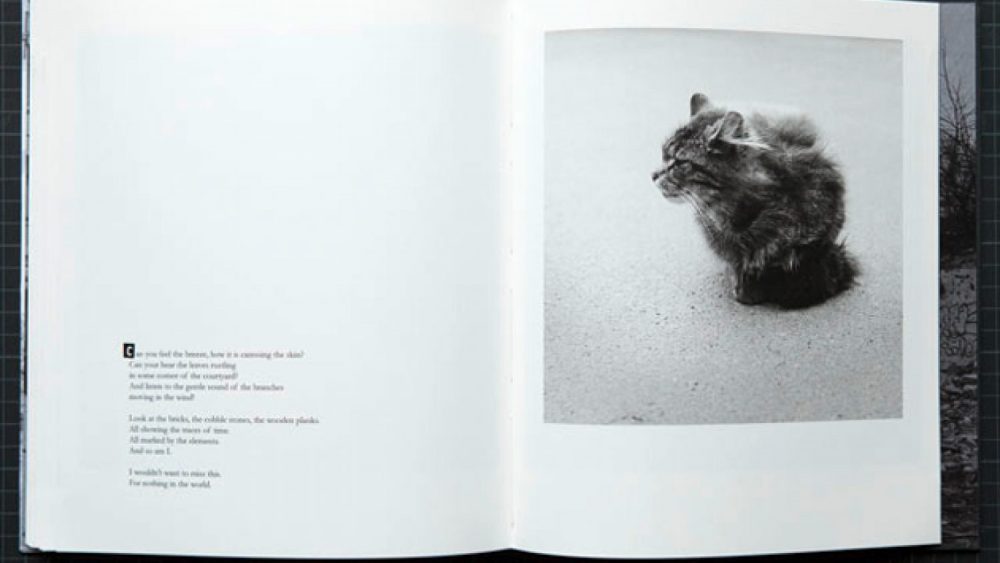

In imagery, not so much revealing discoveries in terms of important issues but for me, the style is the theme, not so much the subject; if a subject allows me to tell something in a certain style, for instance, the Amsterdam traffic panoramas. But there are a lot of things that you can’t cover in your style. It’s a problem when you’re asked to do an assignment; they say that they like your work but then the subject is something I can’t deal with so easily. There are also the cases when it’s the other way round. I made this children’s book about the sheep. I was asked to do it, to introduce the photography into children’s books which was common in the 1950s, 1960s but not later when the drawings, illustrations took the place. I was in the farm at that time and I was sure it should be something visual but didn’t have any particular idea. I took a couple of picture at the farm, it was winter and very cold. Then I started to photograph the sheep and it came out as a Counting sheep book. It’s a very different book but then, at the same time, it’s the same language, the dry observation of something visual. The solutions can be different, it must keep the same recognizable expression. Some people tend to think that the work becomes more personal when you put more emotions in it but it isn’t like that. Tolstoy said that art was fine if it reflected the diversity, the difference. And it’s also the pleasure of sharing things.

How do you really understand the notion “unmistakably Dutch” that you mention in The Netherlands – Off the Shelf?

You see what you see. It is again the style of photographing street sceneries, I wanted to talk about it in a theatrical way. You have an idea of a certain space. I walk around these places, I look for angles where I can possibly hit a couple of very Dutch elements, these kind of middle town places which are definitely in the Netherlands but you wouldn’t know where because they all look similar. The publishing house wanted me to make a book about the changes of the Netherlands but I wanted to make a book about the Netherlands of “why we do it what we do the way how we do it”. I also wanted to photograph the way as if you were looking at it for the very first time. By using mostly empty scenery I force people to look that way. It’s the same if you sit in the theater and let’s say, you sit somewhere at the rear and you look at the stage. The piece starts and they bring in a few typical elements, I do the same in my images – I need some Dutch elements there. Dutch cities, even if they are built in different time, have similar elements as parking spots, glass boxes, benches, so I play a game, the same I did with football, for instance. My context was also to add these catalogue elements in the front, so you immediately look at them in a different way. I was emphasizing the very Dutchness. It’s like your Latvian “eiroremonts” phenomenon. We also have our “eiroremonts” elements in Dutch culture. Here you come to the point where photography is so good in – this dry description.

Most of the photography is, as Martin Parr says, propaganda because somebody pays you to do the job. It’s very unlikely that somebody would order a photographer to go around the Netherlands and photograph a certain square on a certain rainy day – it’s a non-subject for them. The most of the photographs people see are a publicity, no matter if it’s fashion, real estate or a portrait, it has to fit in an idea. It means that there is a blank area which is not photographed. News photography, for instance, is a very limited imagery, very limited way of thinking. When I was photographing in the factory, I wanted everything to be as it was, no special cleaning or arranging but for some people it was a problem as they wanted to make everything more beautiful so that the pictures could be sellable. I pointed out an image of the grandfather who started the factory, it was on the wall as a souvenir from the past. It was made on one day with no other meaning than to show how it was. You don’t have to be nervous about selling all the time. People are not used to look at the reality, it is always distorted, it’s always done for a certain meaning, certain proposal. It’s the same with Facebook. The pictures you have there have nothing to do with how you are but how you want the other people to look at you. This is the time we are living.

Is there something you would call “unmistakably Dutch photography”?

Every now and then you’re invited to be a part of a group exhibition. I was participating in a traveling exhibition about the Dutch landscape photography and suddenly we fall into one group, more or less influenced by each other. Of course, you’re a part of a culture, of people around you, especially, when it comes to Dutch architecture or landscape. It’s more of the mentality how you want to express yourself. But it has nothing to do with photography, it’s more of the type of person, of what you appreciate. Photography is, of course, important for me but most of the things that are done with photography don’t even interest me. I’m not a photography admirer. It’s more about life. Some work really touches you and then you think why. There is a lot to say about it. It’s inevitable that you always show more than you think you show, you always tell more about yourself. I think that the visible world represents the invisible world and it’s very stupid to think that you only show the visible part. Photography is a very limited expressive way of telling somebody many factual things. By editing, you can start playing with what we are going to see; what you talk about is not so much what you literally show but what it represents what you show. You have to be aware of that. It shows very different things. That has always been a nice element of photography, it’s a very specific invention. Life is like a film, it’s always moving, it doesn’t stop or freeze. Yet, a picture is frozen, it’s a strange connotation of something that is already a history. But you always end up with a couple of beautiful possibilities, the sooner you understand these limitations, the better it is. There are still different ways of talking about life. Also in photography. There is no recipe; you have to find it out.