Interview with Yan Morvan

Yan Morvan (1954), often called a pioneer of French photojournalism, was one of the masters at this year’s International Summer School of Photography, leading the workshop Storytelling: the Art and Politics of Photojournalism.

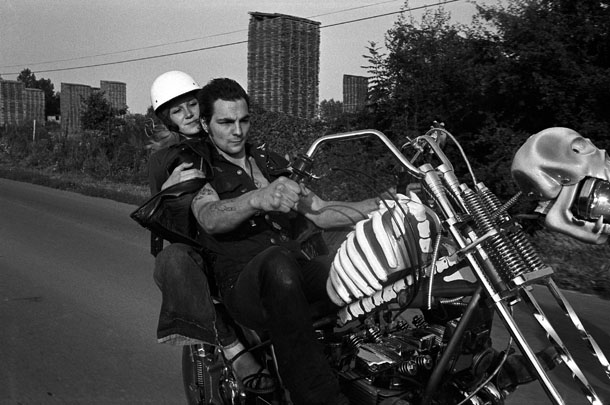

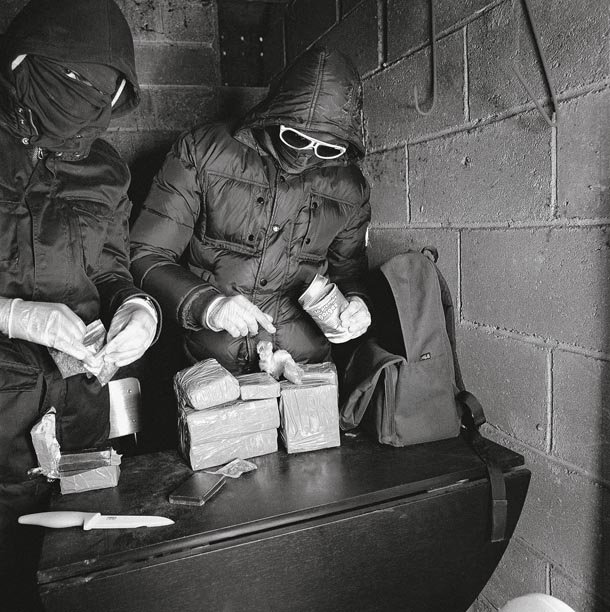

After studying science at university, Morvan turned to photography at the age of 20. Since then he has published numerous books – Bikers, Liban, Gang and Mondosex. His last book – Gangs Story (2012) – was the result of 20 years of work documenting the gangs of Parisian suburbs. In July the book was banned by French court. His subjects have been outlaws, Hell’s Angels, skinheads and prostitutes. Morvan has worked for French publications like Fotolib, Paris Match, Le Figaro Magazine.

In the 1980s, being a staff member of Sipa Press and correspondent for Newsweek, he covered the world’s major war conflicts – Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Philippines, Rwanda, Kosovo and the fall of the Berlin Wall. He has been kidnapped by a serial killer and sentenced to death twice.

As you didn’t study photography, maybe you could talk about how you started out as a photographer.

There were no schools for photography at the time. You had to learn on the field. Are we talking about schools now?

No, we are talking about how you started to photograph, your work.

I don’t work so much. I’m at the bar right now, I was resting in Kuldīga, lying on the grass (laughs). For almost 49 years, I have been making photographs almost every day, telling stories about people. That makes me different from other photographers. I make work like Henri Cartier Bresson, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Eugene Smith. At the time when I started, it was not the practice to talk about yourself. Now photography has become some kind of psychotherapy, people want to talk about their own existence. It started with Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin – the business of photography. It’s difficult to stick pictures of war and dead bodies in your living room. Photography schools were created to fill the new business market and to make pictures for bourgeoisie living rooms.

Where do you want your pictures to be then?

My pictures can’t be stuck on the wall! What do you want to drink? White wine? Two glasses of white wine please! My pictures started with Gangs in 1975. The last picture I did was in Libya where I got arrested. It happened one month ago. I have done a lot of stories in between. During these 40 years I never stopped. I’m always telling the same story – about violence and the fact that power comes from strength.

You said that other photographers are telling stories about themselves, but you are telling stories about other people. But don’t you think that if you have been telling one story all your life, it says a lot about yourself?

Yes, yes, I’m not judging. I never judge anybody. There are different ways. In my time, in the 70s, photographers were also making pictures for consumption. It was not better before. Now people are thinking: who am I, what am I doing on this earth? Of course, when you are 16 years old, you can ask these questions, but, if you still go on even when you’re 50 or 60 years old… You have to move on somewhere from being 16, you know. But let’s talk about the business of photography! Because now it’s becoming a real business. All my students in Kuldīga were asking: “We want to make photographs! But what can we do to make money from it?” That’s the big problem. The market is not so mature. When you go to the Louvre you see paintings, but you don’t see photographs. I don’t know what will happen in the future. I heard people are saying that photojournalism is dying.

So what do you think about it?

It’s okay. The first journalism story was created 40 thousand years ago – drawings on the cave walls. It was a magazine on the rocks, they didn’t have paper. Now we have videos. But the still image is different from the moving image – it’s the same as reading a book and watching a TV story. The future of photography belongs to the upper class people, unfortunately – they will buy magazines and papers. Lower classes will use screens.

Do you think that printed magazines will always exist?

Of course! For the upper class. They are buying magazines for their coffee tables.

When you started forty years ago, there was a lot of money going into photojournalism.

During the 80s there was a lot of money. Someone called that time the golden years of photojournalism. I made money because I spent almost seven years in war. Not many people can make it, so I was paid well. Even now you can make money with photography. Gursky sold his picture for four million dollars. Money goes where the market is. But now there is no money for photojournalism, that’s for sure. Why? There are 150 TV channels, news on the internet are free. Why would you buy a magazine? Even me, I don’t buy magazines, I use the internet. That kills the market. Before you were selling your story for 5000 euros, now the same story costs only 1500 euros. Everything is changing. Maybe tomorrow people will finish with author-portraits and make pictures on the moon.

Well, there are some projects about Mars already.

Yes, I saw a portfolio about Mars in Le Monde. Anyway, I have changed myself. Now I’m making 8×10 inch large format photographs. Have you seen them?

Unfortunately not. You don’t have much work online.

No, I don’t. I really don’t like it. People who want to get in touch with me have to make an effort.

You can afford that in your position, while young photographers have to use every platform to make themselves visible.

It’s different. I have to be a little bit snobbish because it’s part of the game. It’s the same as with women. If she shows everything, nobody is interested. Battlefields, the story I’ve been doing for 10 years already, I have no rights to show. I have a contract with Vera Hoffman (philanthropist, a Swiss publisher – E.G.) from the Hoffman family, they pay for it, they don’t want me to show anything. They will publish the book next year in September. But I haven’t finished the job yet. I have 120 battlefields, I need 60 more. I have to finish in March.

It’s going to be a busy year for you.

It already has been, I haven’t stopped. I have covered Europe, the Pacific Islands, Libya, Israel, America, Vietnam, Japan. I still have to go to North Africa, Egypt, Tunisia, Afghanistan, Syria, Turkey, maybe China. I will try, it’s not easy. But we have to remember the history. You have to know the past to act in the present for the future. I got involved in photography because of my interest in history, not so much because of photography itself. It’s only a tool.

Is there going to be any text in your book?

The publisher would like Umberto Eco to write the text. I have to meet him to see if he is okay to do it. Wait, I’ll show you Battlefields if you haven’t seen it.

How did you choose the places to photograph for Battlefields?

I’m reading all the time. If you saw my place in Paris, there are thousands of books. This is journalism, and Battlefields is my response to the crisis in photojournalism. And at the same time it’s fine art, all mixed together. It tells the story of humanity, the same as my Gangs project. It’s a tribute to the people who died for their country. And the way I work is the same as I work for a news story. It’s a passion. I would love to return to the Pacific Islands, but it costs so much! To New Guinea where Yamamoto was killed, he was the Napoleon of the Japanese (Isoruku Yamamoto, a Japanese Marshal Admiral and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II – E.G.). The plane is still in the jungle, to get there you need three days. I would like to do it, but it would cost around 5000 euros, just for one picture. Two weeks ago I was telling Vera that I have to go to Mexico to make the Camerone story. It’s a very famous battle in the history of the French Foreign Legion. 64 French against several thousand Mexicans. I said: “Vera, if we don’t have Camerone, we cannot make the book”. Vera said “Okay”, she is a passionate woman. I’m living the photographer’s dream.

Do you enjoy this much slower way of taking photographs?

I’m a little fed up with aggressive people. I was in Libya to make a picture and I was arrested four times. The Taliban came to pick me up at my hotel at 12 in the afternoon. I have been sentenced to death two times, I have been kidnapped, tortured. For 40 years I have been making this bloody stuff. Shoot me or not, just don’t talk, I have my picture to make, please leave me alone (laughs). I feel good with an 8×10 inch camera. It’s much crazier than working on a front line.

You think it’s crazier?

Yes (laughs), it’s funny. You know, I was arrested by the North Vietnamese on the border with Laos. They said my camera is a device to connect with American satellites. I answered: “It’s just a wooden camera, a very ancient one”. They kept me in the secret base for four hours.

So they believed you in the end that you are not a spy?

Yes, but they were not happy. There were 20 people involved. They have to find something to punish you for. In the end they said: “We don’t want to see you close to the border anymore”. But it’s okay. I’m from Brittany. People from Brittany are sailors, they go to sea. No matter what happens, they have to bring back the fish. I have to bring back the picture.

It’s probably a really stereotypical idea about photojournalists, but do you feel like you need danger and adrenaline to live a more interesting life, to feel alive?

No, I’m not crazy. I don’t know, it’s strange. I’m not very brave, not very courageous, but the first time I went to war, I was not scared. I don’t like my war photos, it’s something from the past. I earned a lot of money with war photos, but when I spent nine months in Lebanon and almost got killed three or four times, I was not thinking about the money I was making. When your life is in danger, you don’t think about your bank account. The money you win at war is the same as money you win in gambling, you lose it all the time: buying cars, paying for restaurants for my friends, everything. It’s not that I’m not proud. I did it, my war pictures are okay. I never, only one or two times, took a picture of a dead body. I’m suspicious of taking picture of the dead, I want to respect them. When I was working with James Nachtwey, he was spending two hours around a dead man. I couldn’t take one picture. I was thinking, if I photograph dead bodies, the spirit of death will pick on me. In war you start being superstitious. I had my lucky charm, a toy, a little dog, always with me in my bag. If I didn’t have it, I didn’t go. Once I lost the toy and I was completely scared. You live in fear all the time. When I went back to Paris, people would say: “You are a real star!” But what does it matter if tomorrow I might be dead.

Why did you go back then?

The agency wanted to make money. I was a good moneymaker. But luck is like money in the bank, one day it is going to run out. At the beginning it’s all nice light, blue and red, “bam bam”, like a movie. The more you do, the more scared you are. You know that the death is very close. Bullets go past your head. The next time can be the last time.

Don’t you think it changes with age as well, especially when you have a family and kids?

No, no, the problem is experience. I’m still 20 years old in my head. The French photographers who died, I knew them. Ochlik was one of my students. They think they are bulletproof. But they are not, how can you explain? Men want to go to war, to prove themselves, to prove they are adults. I did the same. Not for the same reasons. Now there is a new generation of war photographers. They started with Tunisia, then Egypt, Libya, Syria. In 1982 there was a massacre in Syria, 20 thousand people got killed. I would never go to Syria. It’s not the same as Tunisia or Egypt. I tell them: “Don’t go to Syria, they kill journalists!” And they say: “Oh, we went to Libya already”. Libya is a workshop (laughs). 150 photographers taking pictures of a man shooting at the rock.

Do war photographers usually work in groups?

Yes, but I never do that, I always go alone. For many reasons.

Is it safer to be alone?

Yes, for me it is. I think so. When there is three or four of you, one decides something stupid and there are problems. When you are alone, you make your own decisions. I’m very careful and I’m still alive. I make mistakes, but they are my own. I don’t want a stupid guy with no experience putting me in trouble. The best pictures I have made in war are not from the middle of a battle. You don’t see anything there, only smoke, you cannot make any photos. For a good picture you need to have a good distance. People with no experience want to be in the middle of the battle.

I met a war photographer in Italy who told me that war photographers in groups become like packs, too bold and unafraid.

Exactly! When I’m alone I’m scared all the time. It’s better to be scared all the time and take good pictures than to be thrown in a jail with a friend to joke around with, but without any photos. In war times they didn’t like me, the other photographers.

Because you went everywhere by yourself?

Yes, and I still do. When I go to the gangs, I’m alone. When I’m going to the battlefields, I’m alone. Something happens, never mind, but I don’t want to involve anybody else in my shit. It’s not because of getting exclusive stories, it’s a way to be safe. When I was working with the gangs, I was kidnapped and tortured. It was stupid. After I escaped, I stopped making photographs for two years. When you are at war, you are abroad, but they were at my place, waiting for me every morning. “If you don’t do this and this, we’ll rape your wife and children, we’ll put some acid on them.” They could do it. One was a serial killer.

How did you escape?

Once I had a two-hour chance. I said to my wife: “Pack everything and we’ll go!” We spent two, three months abroad and when we came back they were still waiting for me. But my wife told them: “I don’t want to hear about him anymore, he left, I don’t know where he is.” They were a little bit disappointed, but I was lucky – after some time they got arrested.

You have been lucky a lot of times.

Yes, but someday the luck will run out. Maybe tomorrow. I don’t know what will happen.