Awakening the community. Interview with Vincen Beeckman

Not only does the urban landscape of Brussels constantly come face to face with the interventions of photographer Vincen Beeckman, so does its art scene. While working at Recyclart Art Centre, developing personal and joint projects with the O.S.T. collective and collaborating with such established art spaces as Bozar and Wiels, Vincen brings photography into community projects trying to realize a seemingly utopian, yet genuine idea of bonding the local community. His peculiar self–portraits and the residents of cities near and far captured in photo booths draw attention to the significance and power of the ‘right’ moment in photography that lets you capture both your self-reflection and accidental encounters with strangers.

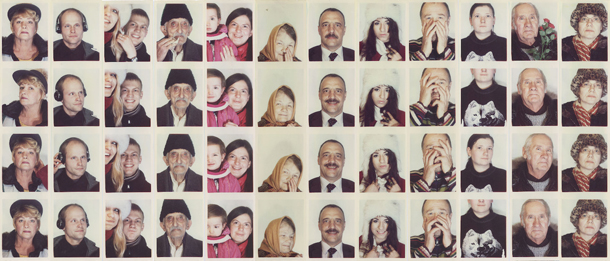

The portraits of Riga residents created during Vincen’s photo booth workshops last year are still on display at the Riga Self/Portraits exhibition at the Tobacco Factory venue until July 27.

In your work photography fuses with community projects. How did this interplay start?

It was after I joined BlowUp photo collective and, instead of doing only black and white photojournalism, we turned to capturing the everyday life of simple people. Back then, just before the year 2000, there weren’t so many photo collectives in Belgium, but it become as huge as self–publishing now.

Then the newborn Recyclart association came up with the idea of documenting the area, in which 60 years ago the urban landscape was disrupted by the dismantling of the North–South junction through Brussels. As train traffic stopped in the city centre, many stations were left abandoned, and one of them – Bruxelles–Chapelle – became the home of Recyclart Art Centre.

They invited us to collaborate and, one day I discovered a leaflet in the copy machine with a proposal for someone who could take care of the area, doing community kind of work. They chose me and I started reflecting the community through photography.

Tell us a bit more about Recyclart and your role in it. What do you hope to change in society through these interventions?

Recyclart is located in a popular area called Les Marolles, and it has a unique identity functioning as a multidisciplinary arts centre that hosts concerts, exhibitions, lectures and artist residencies, as well as a training centre for wood and metalwork, and catering.

I’m the curator of photography and community projects which I bring to life in the public space, connecting people, most of whom neither communicate nor collaborate with each other. TV is destroying their social bonds; they are always at home, not out and about. Photography is a way of initiating a collective lifestyle and connecting people through artistic and social endeavours. I want to enrich people’s artistic awareness and create a lasting result. I experiment with the community, see what works and how I can help.

Which of your projects has had a lasting impact on yourself?

In our recent project Dreams of the old people we make the last big wish of old nursing home residents come true. We’ve been working there for eight years with different photography and video projects. There is this very nice 85–year–old lady called Madame Martin with a memory disorder, so she really wanted to publish her memories in a book for her friends. She has written 32 pages about her philosophy of life and Catholic beliefs, and we discovered her room was full of hundreds of little bits of paper covered in notes of things she mustn’t forget. We decided to publish it, mixed her philosophical and religious views on life with the words of ‘forgetfulness’, and made her portraits in a 300-page-long book.

Do you think your way of using photography in community projects changes how people perceive photography?

Yes, I believe so. You can put on a large exhibition by a famous artist that will gather a great audience, but another idea is to go outside and see what happens – get the community involved by making pictures, and create an exhibition for them.

I did an amateur photo project for Bozar, the biggest Belgian art centre and it drew in twice as many visitors as an exhibition by a renowned artist. We created the exhibition just the same way we would have if the amateurs were serious artists, used the same premises and technical support that the professionals have, and they were so proud of seeing their work in that light!

In a way it revitalizes thinking, initiates involvement, creates communication and understanding among people and builds confidence in personal features. I want these people who don’t consider themselves creative or don’t usually attend artistic gatherings, to see themselves as being able of creating something special. When the media was interviewing one of the artists, they found out that he’s actually a local butcher. And that changes the perception – photography needs to be brought down to the people’s level so that everyone can express themselves through it.

Together with the O.S.T. collective you also made a newspaper for prisoners in Poznan.

Time spent in prison is tough, but this way they could escape it, even if only in their thoughts. They answered philosophical questions, made drawings, collages, named the nicest places in Poznan, where they would like to go, and then we went there to take pictures for them and made their portraits.

In the end, the newspaper was distributed in the streets and at an art centre, and through that they could express something nice and feel like they really achieved something. It changes the public opinion – the prisoner is perceived as an ordinary person, and even if only 10 people discover themselves doing something positive and exchange it with others, it becomes invaluable.

A notable part of your work is portraits of yourself and others. Do you feel that they speak more powerfully to the audience than any other genre of photography?

The best thing about making a portrait is the mutual exchange. I love taking a picture and sending it to the person. It’s the attitude and the connection with humans; the stories about people are more personal. I prefer to meet them on the spot, get to know them and what they’re doing. You cannot speak with the landscape in that way. To tell its story you need to do research, find out what happened there before, the transformations the landscape went through. You can see it, but you won’t know why it has formed like that. With a person you can learn his story directly from him.

You’ve worked on several photo booth projects, two of them in Riga. How did you come up with the idea?

I woke up one morning and it was in my head. Some time ago I took my photo in a booth and noticed that they had switched from the analogue ones that printed four fixed pictures in a row to the digital, which allows you to select the pictures. I was upset by that. So, I thought it could be interesting to capture the people of our area, because in a way it’s a self–portrait. With the help of the wood and metal workers at Recyclart’s training centre, we built the photo booth, but we didn’t have the automatic picture making technology, so I was sitting inside the machine, speaking with people through a microphone and taking pictures. In a funny way it turned out as a confessional just like one, where the priest hears out the sinners.

In Riga, we did the photo booth project just in time before they changed the analogue booths to the digital ones. I like the idea that sometimes people participate in a project for only two minutes, but instantly become a part of a bigger artistic process and the community.

Why do you find the analogue technique more valuable?

I’m caught by its philosophy, that the camera captures the moment you’re in and you cannot change it to make a more beautiful one. Sometimes, people go out too quickly and it’s all white, and it makes the set of pictures interesting and special. And the light in the analogue one is unbelievably good. Everybody looks nice, and I was really lucky that it all came together beautifully.

Most of the people in these photos stand out with something, it seems they hold some story. Have you identified any particular characteristics that would describe the communities in Riga?

Yes, the ones who accept are open minded. If I see someone who would look nice and make a powerful image, I try to push a bit more to persuade him. You can see particular characteristics at a certain place and time of day. It seems to me that people are rather similar in a way, for example, old ladies when the weather is bad.

These people have so many stories, they’re not so fancy and are rather living on the edge, but are nice in their modesty. There was this old man around 60 with red flowers whowas waiting for a woman for a blind date, so the photo also captured his memory of the date. We don’t know what happened in the end, maybe they are still together. It’s this uniqueness, you cannot reproduce that!

Your way of making self–portraits is unusual as well – it appears as an unintentional constatation of ironic and absurd situations. What’s the secret of making it special?

I just look at the situations I’m in. Sometimes they’re funny – the car breaks down, and I have all this baggage and a stupid hat. And I start to play with that. I follow some rules that I have set to do it as a series – the portrait has to be a vertical, full body picture taken from a distance, still and simply straight without angles, and I always have a neutral attitude.

I try to make a portrait every time I travel and all of them are taken by different people. The clothes disappear and I’m getting older – it’s like a personal little story.

The secret to making a good self–portrait can be applied to any other thing you do as well – follow your idea and let it grow, change it along the way, make mistakes. Make the portrait spontaneously, without planning and benefit from the situation and place that you’re in. Don’t believe other people too much if they say it’s bad – do it only for yourself and feel good about it, and then you’ll find someone who shares the same thoughts.