Interview with Joanna Piotrowska

Polish born, London based artists Joanna Piotrowska’s (1985) name has been around a lot since graduating the Royal College of Art, London, in 2013. Her photographic series Frowst – an uncomfortable family album of psychologically charged, staged images, bodies twisted together in sculptural poses – won MACK’s First Book Award last year. She was selected for The Catlin Guide 2014, which showcases Britain’s most talented new artists. Works from Frowst have been included in Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2013 and in the exhibition Jerwood Encounters: Family Politics, curated by Photoworks. Joanna is also among the three winners of the 2015 Jerwood/ Photoworks Awards. Her work has been exhibited in numerous shows in the UK, Poland, Spain, France, Italy, Latvia and Russia. Last fall she spent one month in Latvia in a residency in Kuldīga. Her portraits depicting alcoholics from a rehabilitation centre just outside the town were published in the winter issue of Dazed.

Could you tell me more about the work you did during the residency in Kuldīga?

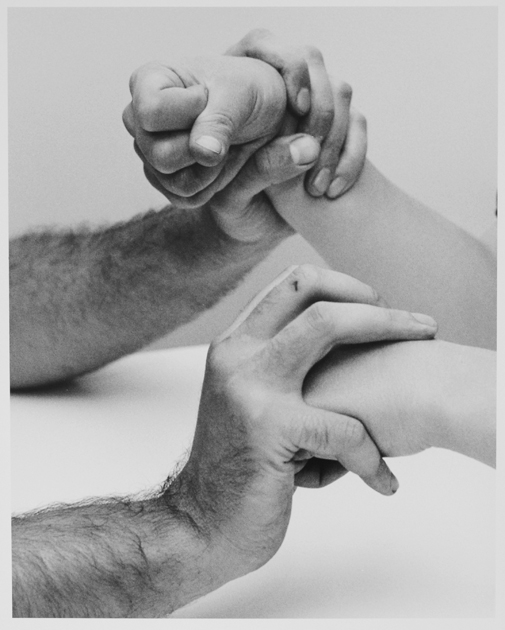

I wanted to try something new, and since I had been thinking for some time about using sound and moving image, I thought it might be a good opportunity to make a video. I invited my friend Nefeli Skarmea, who is a dancer and a curator, to collaborate. She came to Kuldīga for ten days. The original idea was to work with self-defence techniques, and we started with an old Polish manual for self defence from the 1970s, full of aesthetically interesting images of two men fighting. Some of the images in there are quite ambiguous, you can’t really recognise whether it’s people fighting or something else.

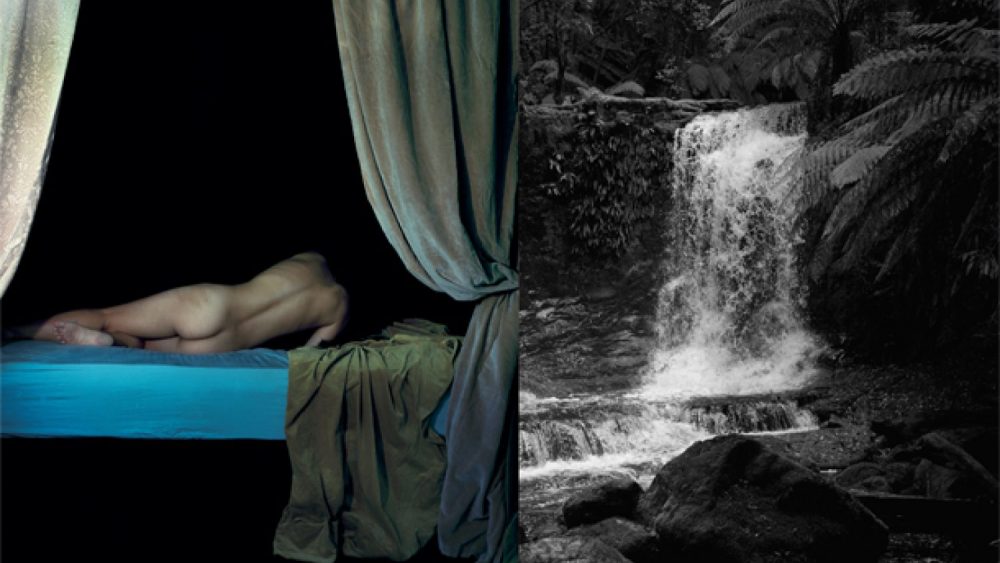

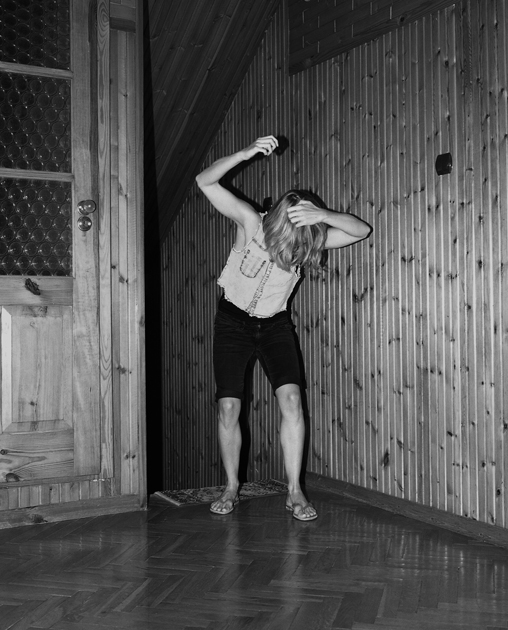

Nefeli has a lot of experience working with the body in performance and dance. Since working on Frowst I have been focused quite a lot on movements and gestures, and how the psychological state can be expressed through the body, so we thought we could combine our experience and knowledge to make a collaborative work. Similarly to my previous work, I wanted to touch upon domesticity, but using the body language taken from attack or defence movements. We chose some movements from the manual to create a short choreography, which Nefeli repeated for the camera. When I worked similarly on the s.w.a.l.k project (abbreviation from “sealed with a loving kiss” – E.G.), withdrawing one person from the image created a weird feeling of suspension. When the attacker is not captured, the purpose of the pose becomes unclear, and the tensed body is turned towards what we cannot see. We tried this with Nefeli, but after noticing that it was also interesting when she held the positions for a very long time, we decided to film it and also make some variations in posing – so there are also sexual positions. I was interested in this moment of exhaustion, the moment when you reach your own limits. Nefeli stayed in the positions for a long time, until her body started to shake and fall. In the final work the screen is divided in two, and on one side Nefeli is doing a sequence of various self-defence movements. She sits at the table repeating several arm and hand movements, and it looks a little bit like she is preparing for a conversation with someone. On the other part of the screen she is holding an uncomfortable position and the camera shows only her face. Observing her face, we follow all the little movements of her eyes and lip as she is trying to be still and to smile, but the tiredness becomes unbearable and she loses control and power of the expression of her face. After a few minutes she gives up.

You also worked with local people.

We were working with a group of girls from the Kuldīga local choir, doing different exercises. We tried this particular breathing exercise you do when giving birth. The video shows close-ups of the faces of girls from the choir, one after another. They are very young, approximately between 12 and 17 years old, and although all of them perform this one breathing exercise, each does it in her own way, which makes me think about their individuality. In the end there is one crop that shows all the girls together breathing simultaneously. This is the moment of the shift from individual to group, but also from private to the general role of women in society. We came up with this idea when thinking about the focus on boosting birth rate in Latvia. And then you have a system supporting young mothers, who can stay at home with their child for a whole year – it’s rare in Europe. I’m curious how such policy influences the very personal decision of having a child and creating a family.

And how about the fashion shoot you did for Dazed at the local rehabilitation centre?

That was a commission. I had never done a fashion shoot before and I’m not really interested in fashion photography, but I though Dazed could be an interesting platform for presenting something what would comment on consumerism and high fashion by showing what does not belong to the world of a wealthy European reader of lifestyle magazines.

Elīza, who was helping me communicate with locals, came up with the idea of going to the centre where alcoholics can live together with their families, and try to overcome the addiction to alcohol through reading the Bible. We talked with them and surprisingly they got quite excited about the idea – I thought it was worth trying. I was excited about the process, about being there, spending time with them and seeing their excitement, but it made me realise that activities like this probably need some previous experience and preparation, because it’s hard to predict their effect. A lot of questions arise from creating such situations, mainly about exploitation of the subject and how the viewer reads such a work.

I saw a project online where there was a fashion shoot…

…with Russian prostitutes?

Yes. I’m not sure how I feel about it.

Well, yes, that’s the thing. I guess when you make a work like this you can sense yourself if it is exploitative or not. If you want to involve somebody with whom you are sincere about the purpose, and if the purpose isn’t morally ambiguous, I guess it’s possible that it turns into a good, socially involved project. But it needs a certain aesthetic as well, and I’m not sure how those two should be combined.

You told me recently that you don’t really like photography.

Yes (laughs). It’s not really that I don’t like photography. I really like old photographs and anonymous, unprofessional photographs are an endless source of inspiration for me. I’m often seduced by a photograph that I see somewhere randomly – is it a newspaper, someone’s family album, charity shop or any photographic archive – there are plenty of them nowadays, digitalised and accessible online. Nein, Onkel by the Archive of Modern Conflict, which often publishes wonderfully edited collections in a book format, is among my favourites, as well as black and white images of blind children touching stuffed animals from the beginning of 20th century which my friend found somewhere online. I still remember some anonymous autochromes of a garden, which I saw many years ago at a little show at the Museum of the City of Krakow, and carte de visite are also often the objects of my admiration. It’s just rare that art photography takes my breath away. I prefer photography that isn’t done by photographers. However, there are many exceptions – I really like John Divola, Roger Ballen, Clare Strand, Anne Collier, I love all Gillian Wearing’s photography works – Signs is one of the best I have ever seen. I love the works of many artists whom I have met in person – Philipp Dorl, Ingo Mittlestaedt, Sarah Jones, Ryan Moule, Victoria Jenkins and others. I know that there are many photographers who enjoy seeing and exploring contemporary photography work, but I do not have any more interest in this particular medium than any other in the visual arts. I think it tends to happen that photographers are such great fans of the medium they use themselves. Some photographers tend to create their own environment, isolated from other arts. I think it would be more beneficial for all not to create these divisions.

Chuck Close said that photography is the easiest medium in which to be competent and the hardest medium in which to have a personal vision.

With a bit of help from other people – usually teachers at college, you can easily make something that looks OK. I think a lot of people pick photography because it’s very easy to create an aesthetically compelling image. There are many photographers whom it’s impossible to tell apart, because they are only fascinated by what something looks like rather than being interested in what something means.

Do you feel restricted by photography at the moment?

Maybe I feel a little bit restricted by what I used to find the most compelling in photography– its stillness and its silence. I was very happy to work with the choir in Kuldīga and I would love to combine images with sounds, objects or writing.

You also told me that you don’t want to work with colour anymore. It seems quite trendy to shoot in black and white at the moment.

It is, yes. I’m not surprised because I’m seduced by black and white as well. But I also think it is really hard to do something that suits black and white. At the end of the day, you can notice some projects that have no real reason for using black and white photography. People do it only because it’s aesthetically very nice. But I might go back to colour – it depends on the project. However, I am overwhelmed by the amount of colour photography, especially those deadpan images in mild colours. But I think it would be challenging to find an interesting idea for a project in colour.

So what’s the reason for shooting in black and white?

In the Frowst series, the forms become more visible and you don’t pay attention to the colour of carpet or wallpaper, to the interior. Although you can still recognise that it is a domestic space, you are much more focused on poses, gazes and forms; the body becomes subjected. Also, there is a strong relation in black and white photography to the documentary tradition. I see this project as a documentation of little domestic performances I did with families. Titling is also quite important – there are only roman numbers in accordance with the order of shootings, like when archiving objects or scenes.

It seems that research plays a big role in your work. 5128 is based on historical events. Frowst not only used old family photographs as a starting point, but is also influenced by Family Constellation therapy. In your newest project s.w.a.l.k. you are looking at self-defence positions. Is it important for you to have a starting point grounded in research?

Research and practice go in parallel, because the practice sets the direction for the research and the other way around.

You said that ideally you would like to live in between London and Poland. That you find London very inspiring, but you can’t make work there.

Being based in between London and somewhere in Poland would be ideal. All the shows I had so far happened in London or thanks to the fact that I live in London. So it’s important for me to be in touch with people from there. The art scene is also more diverse and thanks to that much more inspiring. But on the other hand, it is much easier to work in countries where life isn’t so hectic. To organize a shoot with a family in London is almost impossible, while in Poland it wasn’t such a problem. London is too big and too expensive to handle many organisational details.

Do you think it’s also partly because it might be easier to make new work when you separate your daily life and work? So you go somewhere specifically to make work, where you have no obligations or social life.

Oh, yes, that’s definitely helpful. I think that’s why residencies work so well, because you are suddenly cut off from your everyday life and there are no distractions.

What’s next for you?

I would definitely like to push the work I started to do in Kuldīga with Nefeli forward. And then I think I will focus on new work. I don’t know what it will be, but after doing the videos I already started to miss photography.