Igor Samolet

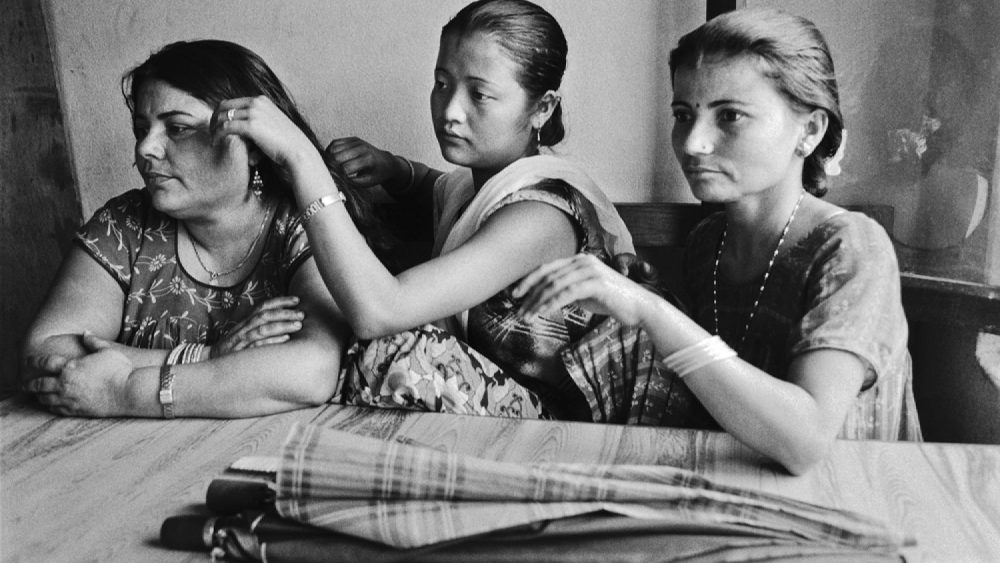

Igor Samolet (1984) is a photographer from Russia, whose work is focused on the mundane and extreme aspects in relationships. In 2013 he published his first book be happy! which was awarded with a silver medal at German Photobook Award 2014. Martin Parr has included this book in the anthology of the world’s photobooks. The Calvert Journal mentions Samolet among the 25 photographers, who have changed the opinion about Russia. He has actively published his works and participates in the exhibitions both in Russia and abroad. Samolet is one of the seven artists, whose works are displayed in the exhibition Territories at the Riga Photomonth 2016, which will be opened on 12 May at the Latvian Railway History Museum. Samolet will also present a public lecture at 3pm on 15 May.

Your project be happy! is very revealing and intimate, not everyone would be ready for something like that. Where did you meet the protagonists and how complicated was it to make them trust you?

In summer, when I returned to the city, where I had been studying for a long time, I saw them on the street. I approached them and asked whether I could make a film about them. The answer was affirmative. However, later I changed my mind about the film and decided to work only in photography. This project was a reflexion on my turbulent, yet undocumented youth. Therefore I did not look for some special methods. Socializing was similar to my friends. All the time we were on the move, we ran and jumped – it was fun.

How did they react upon seeing the images and getting to know about the huge popularity of the collection?

They have grown up now and look at the past with a smile. Now they have a decent and happy family life.

What do you think about the lifestyle you are showing in your images?

When I took the images, I was not aiming at social criticism or showing attitude towards the surroundings, I was simply on the move. However, going through the selection process, I realised that for me it is more important to show the feelings that are most important to young people: the first love, friendship, sex. They are the cause for all activities. At the same time, when taking photographs, I tried to catch the everyday life on the background, and that is what creates the impression of chaos. The activities, to my mind, are completely in tune with the age of my protagonists. I know it all very well.

This project has managed to attract a lot of attention in a short period of time starting from the popularity and acknowledgment in Europe and ending with an opposite reaction in your homeland Russia. For example, The Calvert Journal published an article mentioning 10 exhibitions that had caused huge resonance in Russia. It is said that in the Bogorodskoja gallery in Moscow your exhibition was closed on the very opening day due to the sexual imagery. What is your attitude towards that? Have you had similar incidents?

In Russia, similarly to any other country, there is a place for the good and the bad, and I have included it in my work. Of course, we want the grass greener and the light brighter, but unfortunately it is not always the case in real life. I prefer to solve the problems openly, not to avoid them, but in Russia it is common to avoid them. The exhibition at the Bogorodskoja gallery was closed due to the censorship. Yes, there is sexual imagery, but it is part of history. It is complicated to tell a story about young people without addressing the issue of sexual identity. Nowadays everything that is exhibited in Russia is directly or indirectly subjected to the censorship. Activists can come and smash everything they don’t like.

I have a couple of works, where I reveal extremes or address especially sensitive questions, and not always such works can be displayed. I take it as a fact.

What is your current project?

I am trying to finish the photobook Steam, which is about a young man, who is looking for happiness and finds it in sex. It is a story about the stuffy Moscow, loneliness and money. In the epilogue I refer to Dostoyevsky’s words: “Pass by us and forgive us our happiness.”