Interview with Anouk Kruithof

Anouk Kruithof (1981) is a Dutch artist living and working in Mexico City, New York and Amsterdam. Her works take the form of photographs, sculptures, artist-books, installations, texts, printed take-away ephemera, video and performance. She has exhibited internationally at such institutions as MoMA, New York, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Sprengel Museum, Hannover, and Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow. Kruithof is also the director of the Anamorphosis Prize which is still open to all self-published photobooks and photo-based artist books published between 1 September 2015 and 1 September 2016.

From 6 to 14 August, Kruithof visited Latvia where she presented her work and was one of the masters at this year’s International Summer School of Photography (ISSP), hosting the workshop Photography as a Starting Point.

It seems that throughout your career you’ve been pushing the potential of photography’s medium. You are moving quite far away from what we understand as the traditional photography. Can you explain where your interest comes from?

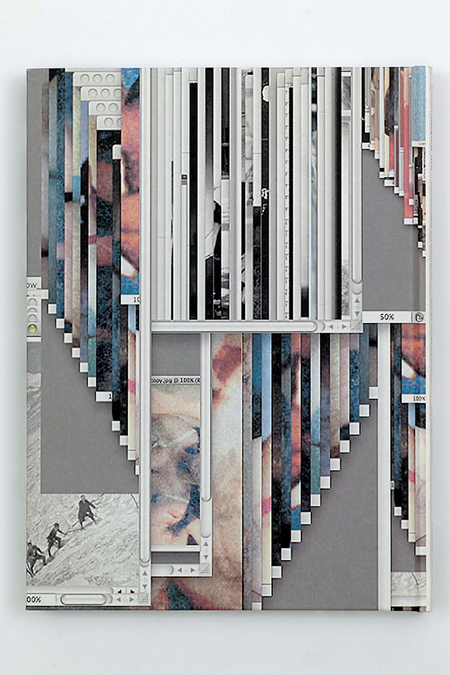

I have never presented photography in a straight way like a photo series. This medium has always frustrated me. I got a bit stressed by limitations of photography because of the fact that it’s always a surface of something. And then this print, a rectangle on the wall. I questioned the media because I think you can do more than only tell linear stories with photography.

Yet, your project Daily Exhaustion with self-portraits is quite photographic.

Yes, it is. Also there is The Black Hole, Becoming Blue, Playing Borders, and The Daily Exhaustion that was a small project, which I made with a small digital camera. Then I made a little newspaper that was spread around for free. But mostly I work with three dimensional installations or books. I always reflect on actuality or something that catches my interest in where I live. I am moving and travelling a lot. It has already been nine years since I’m not living in the Netherlands. Living in Berlin and later in New York also inspired me for certain topics, which were addressed in my projects.

Which are the main topics you got from New York?

In New York I started to reflect on what was going on in this intense city, mostly with people’s mind. For example, the insanity of a very stress driven town. I got inspired and created a project Everything is a Wave. When I was in New York, I did a lot of interventions in the public domain about that subject. The pressure, success and power games became issues. I did a work called Push-up where I asked businessmen in their breaks to do as many pushups as they could on the street, then I photographed them. The businessmen were always accompanied by a bunch of bodyguards, who came and sent us away because the stoop where these men did the pushups was a private property. If they broke their arm or something, they could sue the company. Those invisible borders are everywhere in New York, especially between the private and the public spaces. And that’s an interesting “space”.

How these borders in New York differ from what you have experienced living in Europe?

In my opinion, America is a fear-driven society. It’s extreme, because of its financial power. It’s even more visible in the financial industries or in the middle of the town where you have all the big corporations. You notice paranoia and surveyors that have control over people. You can see a lot of differences when comparing America to other parts of the world, because it’s a really powerful country, which comes with extremes, positive and negative.

Your latest works are more performative and abstract, but other series like #Evidence, Sweaty Sculptures, Unshielded Window are more sculptural. How did you arrive to this style and where did you get your inspiration?

I can be inspired by anything –interviews with people about the topics that interest me, reading, etc. I’m never uninspired. I’m way more often inspired by sculptors, architects and people who work with space and music, and dancers, and scientists. I usually think about the presentation and how photos work in the exhibition space, public space and how they encounter with audience. I also find it interesting to talk and think about. So if you start doing that, you’re going to work differently with photography.

What does the medium of photography mean to you?

For me it’s like a vehicle of a lot of possibilities and at the same time it’s a restrain. They both have a big contrast and I like to work with it because this contrast frustrates me. I like to print photos on other materials than paper. So the photos become flexible. And I like that the photo can be used as an enormous wallpaper, it can be a stamp, it can be a thousand page book and it can be used online. Photography is everywhere now and I like that it’s democratic. Almost everybody has access to it and it’s not a professional thing anymore. Thinking about photography is more important, because everybody can make photos. If someone is able to show his or her work in the museum, it does not necessarily mean that it’s good. It’s all about what an author thinks and wants to tell with the work. You can find interesting images made by students but you can also find them online made by an anonymous amateurs. Good photography is everywhere now.

As you are a co-creator, director and jury member of the new Anamorphosis Prize, how would you describe the subjects of the last year’s entries, what do they tell you about the situation in photobooks and photography today?

Last year we had the first edition and we received 336 books. The books came from all over the world with different ages [of applicants] and very different levels of quality. The question is hard to answer because the variety of 336 books is huge. Even the 20 shortlisted books are very different from each other.

Could you describe the way books are selected?

We have 3 experts. I’m a bookmaker and an artist. John Phelan is a collector and he also has a specialty in self-publishing, as he has thousands of books and he is very knowledgeable. Charlotte Cotton is also very knowledgeable in photography in general and is an acclaimed curator. So it was just us looking at these books and the rules we set up were essentially based only on our personal knowledge and experience.

You often work with mixed media, found objects, image archives and different kind of unconventional materials. For example, why did you chose to use selfie stick as a part of your project #Evidence?

The selfie stick is the most absurd new object that emphasizes self-representation. You don’t need to connect with the people anymore, but that’s also why it’s bizarre. I think it’s a questionable device. For example it’s absurd how many people used it in the 9/11 memorial in New York. People were constantly taking selfies with their selfie sticks and I think it’s really inappropriate in places like that. It’s like – hey look at me, how great I am in front of a historical monument with its tragic memory. This self-representing tool comes in handy for making the best selfies as well. And a good selfie apparently means a lot to people these days. A good selfie is more meaningful than socialization with a group of people or actually being somewhere for real, or understanding something.

Does technology respond to the age that we live in or does it define that age?

It defines the age, but it’s about the accessibility as well.

Maybe it is also about the fact that we’re becoming more isolated with all these technological things. Are we moving more quickly to a world in which we don’t need anyone?

Yes, of course. That’s also what I thought about. You don’t need to ask someone to take a picture anymore, you don’t need to be afraid that your phone could get stolen when you give it to someone. Technology slowly takes over and this digitalization is slowly changing humans.

You are also using and combining different kinds of social networks, especially Instagram. How do social platforms like Facebook and Instagram impact us? Do they help us to connect with each other or do they physically disconnect us?

I think it’s an old-fashioned idea. Children grow up with that and it’s really hard to judge from our perspective, because people who get older always say that it used to be better. But for them it might be actual. There is a lot of research showing that they feel even more connected by chatting the whole afternoon on their phones instead of playing ball games outside. I think it’s impossible for adults to judge what is better, because they didn’t have that when they were young. You can’t say if that’s good or bad for children. Probably it’s neither. It’s there and you just have to accept it. And deal with it in the way you think is the best.

You don’t see anything bad there?

Of course, I see that a normal physical contact and having children outside playing brings them in the nature and that’s still beneficial. I believe that if I had children myself I would also educate them and show that other things are possible, too. But I already know that if I had a kid, at six or seven he would want to do those things because now it’s just natural in our lives. That’s because everybody else has it. Maybe it’s bad that they get addicted to their cellphones, but, on the other hand, maybe there would be less child-rape because kids play less outside in the forests. I think it’s better to go with what’s going on and try to understand why they change, why it’s important for them and listen to this.

You are really productive. On your website I noticed that you have 2-5 different projects every year. How do you organize your practice?

I am a workaholic and I always work. In my life I am quite work-based but I really love it even if I’m always busy making my work from morning until evening.

Do you work mostly in the open studio, on location, behind your computer, on the streets – or how do you divide this?

That’s a difficult question because I have no home for 8 months already. I live everywhere in a lot of different places.

How is that possible?

For example, I am living here now. I am travelling a lot for work and my art. Or I go to lectures, to photograph or for an interview or I am somewhere else doing research. It’s really not one thing. If you are deeply in the process of making a book then you are busy with editing it with a designer, every single day by the computer, cutting photos and it’s only in the studio. But sometimes it’s not that way because I need to write. I can do a lot of different things at the same time. I have everything in my head and I never forget anything.

Could you describe how you manage your no-home lifestyle with your creative practice? Have there been any amusing incidents or difficulties?

The performance called Connection I did in the Tate was a bit too crazy. I was in Beijing printing my book Automagic that’s coming out soon, so every day I had to be in the factory and control the process. At the same time in breaks I was busy preparing the performance. That was intense while living in a super sexy IBIS hotel room. It wasn’t ideal but I could do it.

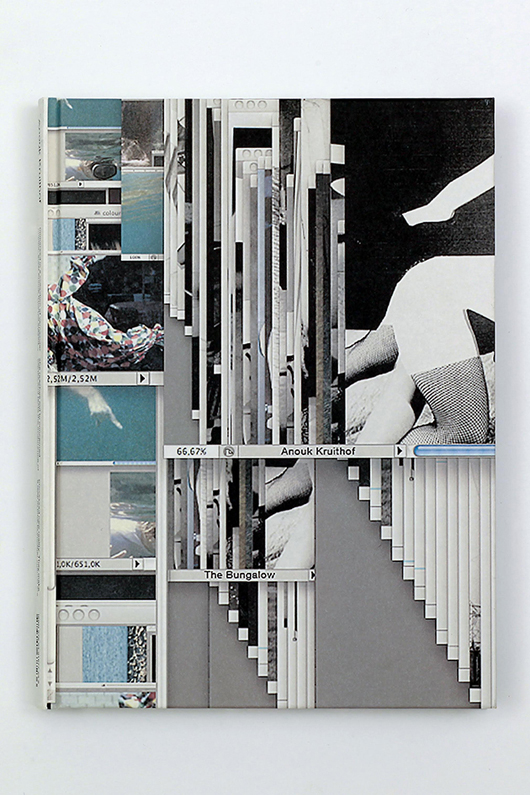

But when I was making the Bungalow book I locked myself up in a bungalow in a really small village called Ouddorp in the Netherlands close to the sea. I called my book after this bungalow obviously, but there was no direct connection to this space except for me being there with my selection out of Brad Feuerhelm’s vernacular photo archive and I was working with it and had no WIFI. There was nothing around me, no internet, no other people. I was completely alone. I was super concentrated for 5 weeks. People think I am really social but I am a Gemini, I am a loner, too, and have really 2 different sides.