Interview with Dirk Braeckman

In an interview for a Belgian weekly a couple of years back Dirk Braeckman (1958) described his work as a journey – he meets someone, spends some time with them, and then either takes a photograph or doesn’t. This receptivity towards the world is present in his images – they transmit the feeling that even though it often doesn’t make sense to conceptualize an experience, that doesn’t mean it’s not possible to say anything about it. “The job of the photographer, in my view, is not to catalogue indisputable fact but to try to be coherent about intuition and hope,” Robert Adams wrote in his classic Beauty in Photography.

Braeckman lives and works in Ghent, Belgium. During the last couple of years he has had solo shows in LE BAL (Paris), De Pont (Tillburg), De Appel (Amsterdam), among other places. He is a guest lecturer at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. Braeckman will represent Belgium in the upcoming 57th Venice Biennale, opening May 13.

Could you tell us a bit about the upcoming Venice Biennale exhibition?

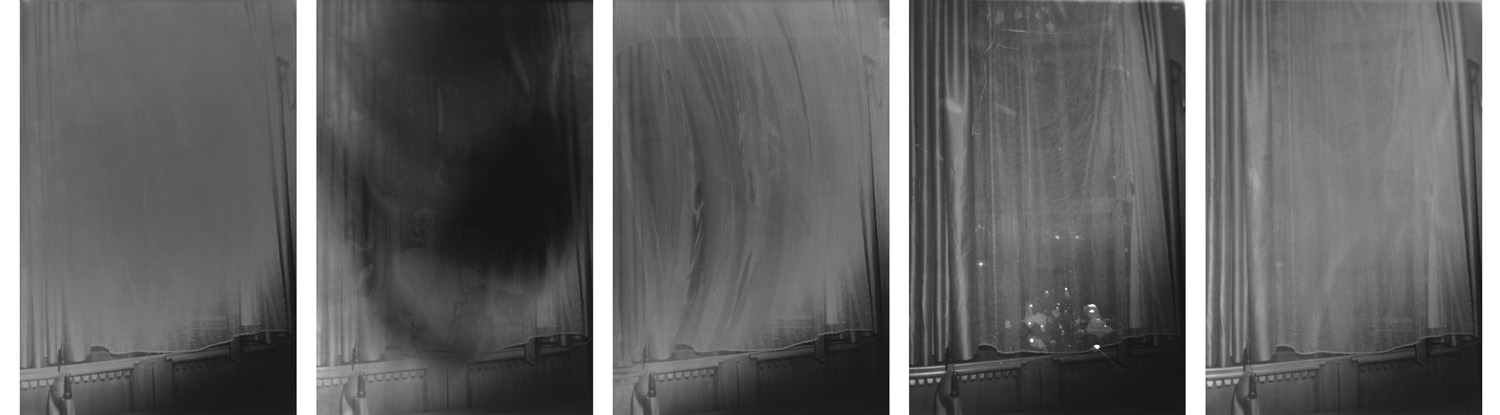

The exhibition in the Belgian pavilion will mainly consist of new monumental photographic pieces on baryta paper; unique prints I create in my dark room, a space that functions as an artist’s studio for me. My recent work is a response to the multitude and speed of images today. Slowness and resistance are core to both the creation process as well as the images themselves. It’s not about photographs that can be duplicated or recognized at a glance. It’s about powerful images that don’t reveal everything and allow their meaning to be shaped in dialogue with the viewer. Quiet moments brewing with action incite the viewer to speculate and create their own potential stories.

Usually we don’t see a lot of photographic work at the Biennale – do you feel there is still a divide between contemporary art and photography?

For me, there is a difference between artists using the medium of photography in their practice, on one side (Arnulf Rainer, Richard Prince, Jan Vercruysse, for instance), and photographers making artworks, on the other side (such as Jeff Wall, Wolfgang Tillmans, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff). These are two different angles. Some people say that in certain countries like Germany or the Netherlands photography is more ‘accepted’ as an artistic medium or even an autonomous discipline, whereas in Belgium it is still considered inferior to other artistic media. I have never thought in terms of countries or even the position of the medium, I just continued to do what I have been doing for 30 years now, making images.

You experiment a lot in the darkroom, working with images in a very physical way, and also doing such things as taking pictures of pictures. It would be easy to describe it as, say, an exploration of the medium – thinking about photography visually. Whilst speaking about your own work you often stress that it’s about the ‘experience’ of it. As your work visually is very impelling and feels very intuitive in the way it has been created, I wonder, whether your aim is to also give some sort of conceptual statement regarding the medium of photography, or is it about something else?

I am not at all a conceptual artist, although many interpret my work in this way. It is true that I question the medium of photography and still use it as my tool. Nevertheless, to me it is all about the image, not the idea.

Analogue processes are key to your working method. How do you feel about the future of analogue photography and darkroom printing?

I use analogue photography because that’s the medium that I learned at the academy and I’m trained in it, it became my way of working, my tool – more as a coincidence than anything else. My aim is to create interesting images. I have nothing against digital photography, sometimes when I want to have colour or go large-scale, I opt for digital. But I really enjoy the developing process, it encapsulates my whole artistic approach. I think analogue photography and darkroom printing will become more and more difficult as all the necessary materials are getting more expensive and rare. Perhaps they will stop producing them altogether due to the very low demand. Having said that, there is still noteworthy interest in the analogue technique. Nevertheless, I don’t feel I am dependent on supplies. I will find other resources or work on my own solutions if needed, such as making my own paper, if this proves necessary.

The visual consistency in your work is astonishing – how do you accomplish that?

To me it comes naturally; that’s the way I create images. Rather than pursuing different themes or numerous distinct series, I retain a consistent approach to narrative, aesthetics and visual motifs.

Nowadays we live in a world of images where each individual picture becomes less and less significant.

In a world of fast-paced image-making, yours is still quite slow. Do you think one image can become more meaningful than another? If yes, in what way?

I always perform a visual exercise to judge my work: I try to look into the future and wonder how I will look at a particular photograph in 15 – 20 years. The question is: will the image feel out-dated or will it still intrigue me? To me this is of the utmost importance, trying to find this kind of timelessness.

Besides this, I am also interested in the viewer and his own perception. I want my images to not be instantly recognizable, but rather invite people to invest time and effort in order to read and appreciate them. My work offers a different experience, another way of dealing with images. I don’t like to compare or define what’s more meaningful. I personally don’t hanker after instant gratification. Most of the time I visit places and don’t take a single photo for days. So in that sense I don’t follow Bresson’s idea of the “decisive moment”; I need to feel a place, engage with it and get to know its character before I decide to capture it. I take photos in a very spontaneous manner, nothing is pre-planned.

We don’t really see any men in your images, most of the characters are women. Is there a reason for that?

There are some men in my photos, even myself included sometimes. My subject matter derives from my immediate surroundings, so it’s not pre-calculated or planned. I suppose my eye is attracted to the female form as I connect it to a certain kind of atmosphere and aesthetic that appeals to me.

The titles of your works are very vague and abstract, consisting mainly of combinations of letters and numbers. What do they signify for you? Do you feel text goes against the visual meaning of your work?

Everyone is curious about the mysterious code of my titles. But it’s actually quite simple: I don’t want my titles to be descriptive or didactic; I don’t want them to reveal anything about the image or when and where it was taken. I simply give my pieces titles that contain a letter combination and the date that the print was developed. The letter combination is merely for archiving purposes. Thus, no information is given away. I want the viewer to experience my images with no preconceptions.

In contrast to many artists and photographers nowadays, you don’t work within this frame of ‘project-based’ thinking, you just continually develop your work. Artists are more and more pressured to rationalize and conceptualize what they do – how do you feel about this? Why do you avoid making ‘projects’?

I don’t avoid making projects per se. Often when I’m invited to work on a project, I accept the commission if it suits my point of view and ongoing body of work. I suppose it’s just a matter of preference; I continually develop and add to the artistic voice that I established for myself early on. What appeals to me as an artist hasn’t changed and I like the idea that you cannot tell which work belongs to which phase of my career (unless of course you’re extensively familiar with my trajectory).

What advice would you give to young artists nowadays?

Try to find your own signature and your own way of doing things, without comparing yourself with others too often.