Underexposed Photographers: Life Magazine and Photojournalists’ Social Status in the 1950s

“You see, a document has use, whereas art is really useless. Therefore art is never a document,” said American photographer Walker Evans (1903–1975). 1)Leslie Katz, An Interview with Walker Evans (1971), in Vicki Goldberg, ed., Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988: 359-369), 364-5. Emphasis in original. But is it always so? Although these concepts are unclear and contested even today, now we are used to seeing documentary images by photographers such as Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson or Robert Doisneau as fine art prints in art museums and galleries. But it is easy to overlook that most of these images, now well-known artworks, were initially made for the magazine page where the photographer’s name often went unnoticed. Things began to change in the 1950s, when photographers and especially photojournalists emerged as a global “creative class.” 2)The phrase “creative class” is used here as a way to describe people who share the conditions, tools, and skills of their creative work, but who do not form a close ideological allegiance such as a “group” does. The phrase “creative class” has been applied to contemporary cultural studies and popularized by Richard Florida since he published The Rise of the Creative Class in 2002. See the most recent and updated edition: Richard L. Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: Revisited (New York: Basic Books, 2012). Photojournalists believed that their work is creative and wanted to present their images as art. They desired to reach the elevated social status of artists. The US-based illustrated weekly magazine Life was instrumental in the process of photographers gaining recognition and global exposure. However, this process was neither smooth nor free of obstacles. This article aims to shed light on some of the obstacles that the photographers of the 1950s met in their way to reaching recognition as artists.

That a journalist can be an artist—or rather, more precisely, that an artist can be a journalist—was most visibly demonstrated by French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004). The 1950s was the time when illustrated magazines flourished across the world. The US-based Life and its counterparts in other countries—such as Il Mondo in Italy or Stern in West Germany—popularized the documentary image. Although Cartier-Bresson’s career as artist and photographer already took off in the 1930s, Life commissions solidified his global fame and the reputation of a generation’s leading photojournalist. For many photographers in the 1950s, Cartier-Bresson’s career and achievements served as an inspirational example. He proved that artist and photojournalist are not mutually exclusive professions and that documentary images can also be art. Yet hundreds and thousands of photographers who provided content for the illustrated press on a daily basis did not always feel appreciated for their creativity and skills. The day-to-day business of photojournalism was highly utilitarian and largely dictated by the newspaper’s or magazine’s editors. In the magazines of the 1950s, the editor was the star, not the photographer.

Typically, the only moment when the photographer was in control was pressing the shutter. Photographers were expected to supply “raw material”—negatives from a location, made according to the guidelines developed by the editors. The rest was done by others, including developing the film, making contact prints, selecting shots for enlargements, composing the narrative of the picture story, and making layouts for the page. Photographers did not have a say in how their work was organized and captioned on the published page. Wilson Hicks, picture editor of the Life magazine from 1937 to 1950, admitted that becoming a photojournalist was never a justifiable career goal. According to him, any photographer’s only career aspiration was to become an editor: “the photographic journalist of tomorrow should be a bachelor of arts, a master of photography, a doctor of journalism. Then, in tomorrow’s World of the Image, he could become an editor someday, whereas today he is prepared only to be a photographer.” 3)Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 111. Emphasis mine—A.T. Reflecting upon the social hierarchy from Life magazine’s perspective, Hicks clearly states that “The efforts of writer, photographer, reporter or researcher, assignment editor, art director, and others converge when the editor performs the crucial act of selecting the photographs for a picture story and determining … the point of view from which the story is to be presented.” 4)Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 48. See also a historical account of the daily work at the Life magazine editorial offices: Loudon Wainwright, The Great American Magazine: An inside History of Life (New York: Knopf, 1986). Even the superstars of photography of this time were subject to the same workflow. While describing Cartier-Bresson’s work for Magnum cooperative, art historian Peter Galassi observes, “Even photographers who strived to edit their own work into coherent stories (as Magnum members generally did) had virtually no control once the pictures were handed over to the magazine.” 5)Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), 48. Indeed, this streamlined workflow of the magazine industry often limited photographers’ creative autonomy and took away control and authority over their own work.

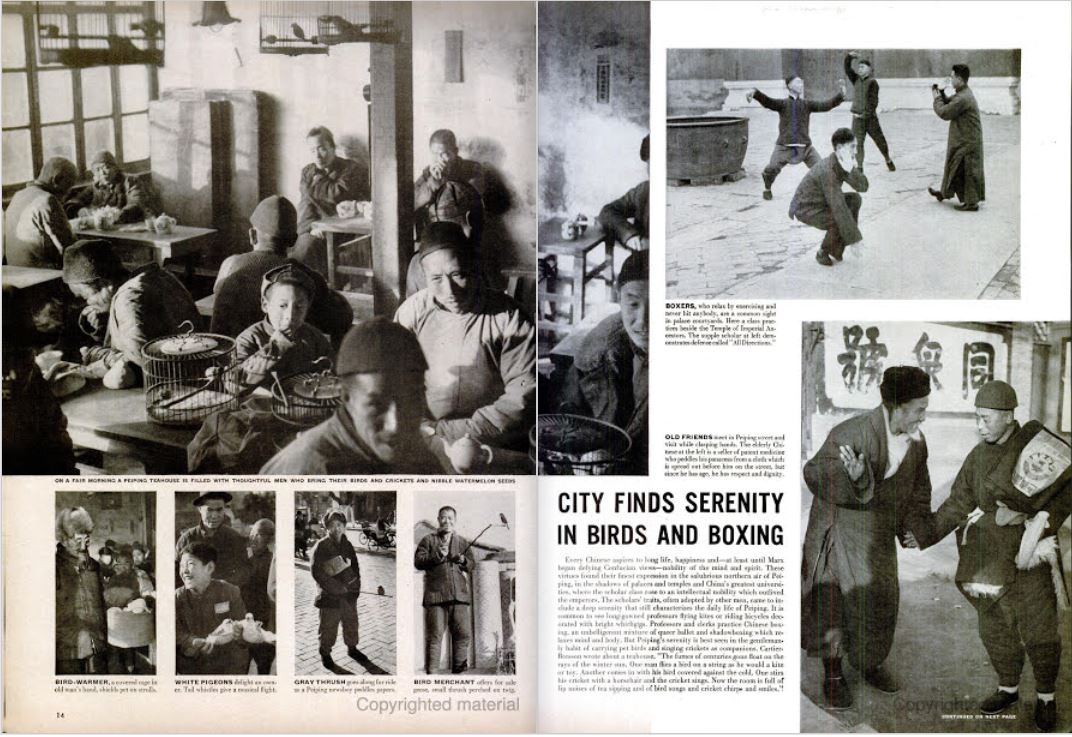

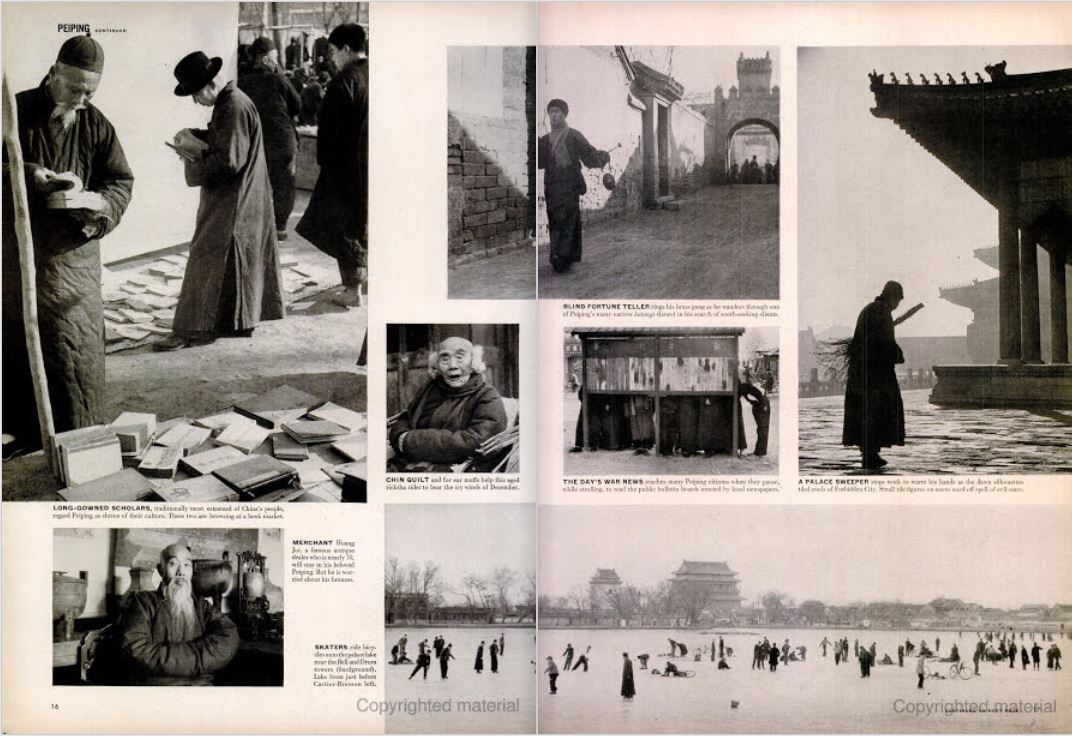

Galassi in general is critical of “the compromises and disappointments of group journalism and the picture-story format.” 6)Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), 57. Yet, despite its authoritarian approach to photographers’ work, Life was instrumental in providing them with opportunities to exercise their creativity and produce work that later gained art status. Art historian Nadya Bair discusses Cartier-Bresson’s Life assignment to immediately leave Burma, where he was at the time, for China in late November 1948. His task was to provide images for photo essays, closely following instructions by the magazine’s managing editor Ed Thompson. 7)Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2 (2016): 146–166. These instructions consisted of obvious cultural stereotypes, as the editor asked for images that would look like images that people had already seen. As Bair points out, Thompson’s telegram among other details requested “… finest scholars merchants opera lovers bankers bird fanciers … get faces of quiet old men whose hands are clasped around covered cups of jasmine tea.” 8)Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2(2016: 146–166), 151. The images that Cartier-Bresson produced largely corresponded to these requirements, as they appeared in the January 3, 1949 issue of Life (especially on pages 14–17). However, Bair also argues that the magazine editors’ instructions oftentimes provided a useful “roadmap” for the photographer to be in the right place at the right time, like at the Shanghai bank in December 1948. Part of a larger assignment from Life, Cartier-Bresson’s well-known photograph Shanghai, December 1948 is one of the images that were widely circulated and for many westerners became a canonical representation of the social tumult in China. 9)Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2 (2016: 146–166), 151. The image captures a crowd queueing in front of a bank to exchange paper money for gold in the midst of a deep economic crisis. 10)“With the gold rush, in December, thousands came out and waited in line for hours. The police, equipped with the remnants of the armies of the International Concession, made only a gesture toward maintaining order. Ten people were crushed to death.” Magnum Photos, Image Reference PAR170018 (HCB1948002W00295/15), available online at https://pro.magnumphotos.com/image/PAR170018.html The women and men are obviously in great physical and emotional distress, as the contorted, uncomfortable postures and worried facial expressions demonstrate. Although it is a documentary image, the scene has an eerie theatrical quality—the arms of the people desperately clinging to each other appear to be choreographed to create a forceful, violent human wave running horizontally throughout the whole frame. It has to be noted that while Life editors provided the photographer with the time and location of an event, they did not prescribe its visual treatment. The editors’ instructions, although they may sound limiting, gave Cartier-Bresson useful information about where and what was happening. As Bair has shown, always being in the right place at the right time was essential for the photographer to continuously produce the intense and varied images for which he became famous. The dissemination of these images in the pages of Life further cemented Cartier-Bresson’s reputation and introduced his work to broad audiences in the US as well as internationally.

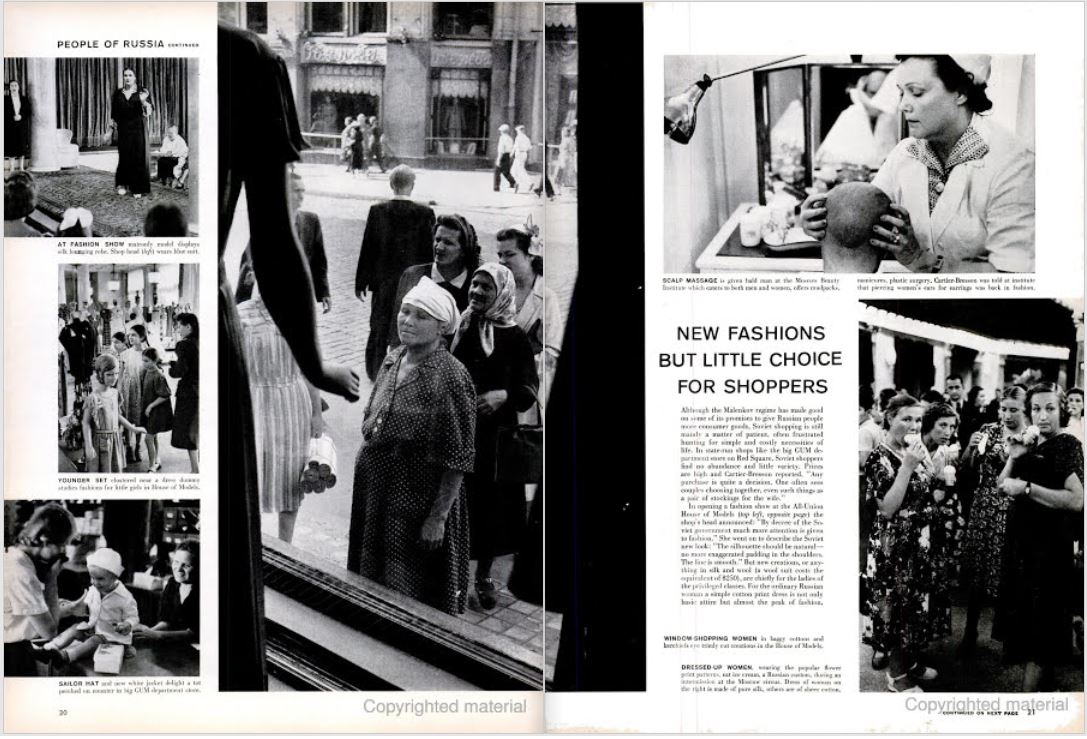

Cartier-Bresson, however, was one of the few exceptions. In the publishing industry’s hierarchy, the average photojournalist was still an unprivileged worker, a self-taught man at the bottom of the power pyramid. He was almost always a man, because photojournalism in the 1950s was a typically male profession, despite the few notable exceptions like the American photographer Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) or German-born French photographer Gisèle Freund (1908–2000). Women were most often employed by publishers in office jobs such as fact checkers and researchers. Hicks perfectly characterized the typical career path of a photojournalist: “Not all, but a good many photographers … have come up the hard way. College graduates among them are in the minority. … A favorite progression on newspapers and in newspicture [sic] services has been from motorcycle messenger to office boy to darkroom worker to photographer.” 11)Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 110. Only in a few exceptional cases did the photographer’s name make it to the cover of Life, such as Cartier-Bresson’s name on the cover of the January 17, 1955 issue featuring his reportage on everyday life in Russia. On average, photographers were unimportant, and their names most typically appeared inconspicuously in small print, if at all. Such a lowly perception of photojournalists’ professional status was by no means limited to the US. For example, the illustrated weekly Il Mondo, one of the leading magazines in postwar Italy, did not even credit the photographers during the 1950s. 12)Maria Antonella Pelizzari notes that “no photographers were acknowledged by name before 1959.” Maria Antonella Pelizzari, Photography and Italy (London: Reaktion, 2011), 122. Photographers were treated by the editorial staff as “artisans” and “like cobblers.” 13)Martina Caruso, Italian Humanist Photography from Fascism to the Cold War (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 130. A publication in such a magazine, nevertheless, was highly desired among photographers. The magazine was what readers appreciated, but they did not care that much for the photographers who had provided the visual content.

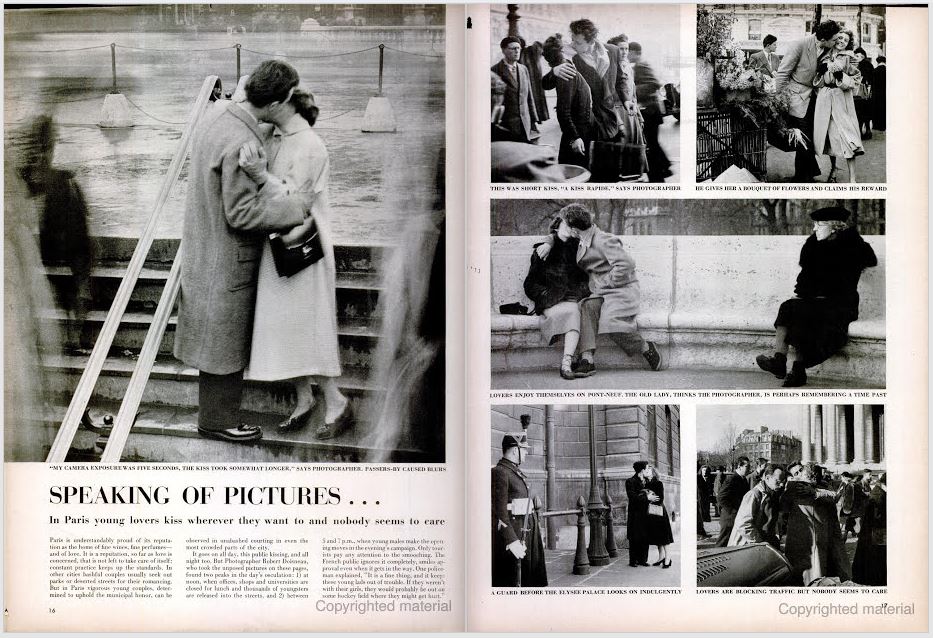

Even when the photographer was credited, one had to search for their name. Let us consider one of the iconic images of the 1950s, The Kiss by the Town Hall (I 1950) by French photographer Robert Doisneau (1912–1994). The image is part of a series on young lovers in the streets of Paris, commissioned by Life. The commission was based on American cultural stereotypes about Paris as a city of lovers. The photographer fulfilled the editors’ request by organizing a photoshoot with young actors in recognizable Parisian locations. 14)Peter Hamilton, “‘A poetry of the streets?’ Documenting Frenchness in an Era of Reconstruction: Humanist Photography 1935–1960,” in Norman Buford, ed., The Documentary Impulse in French Literature (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001), 177–219; Nina Lager Vestberg, Robert Doisneau and the Making of a Universal Cliché, History of Photography 35, no. 2 (2011): 157-165. The images that made the cut were the ones where the young couples were embracing and kissing in public spaces, ignored by the passers-by.

Today we are used to see images like Doisneau’s in museum and gallery exhibitions as artworks—as nicely printed enlargements, framed and protected by glass, neatly arranged on pristine white walls. But let us remember that these images were initially made for a photo essay in Life. On the magazine page, the photographer was not yet presented as a great artist. The first spread of Doisneau’s series on Parisian lovers in the June 12, 1950 issue of Life is a typical example. Approximately three quarters of the first page is taken up by the lead photograph, cropped to a square format and set to bleed on three sides of the page for maximum visual impact. The editors selected this image to attract attention: it focuses on a couple embracing and kissing while standing on the middle of staircase, while the surrounding busy traffic and passers-by are captured as a mere blur. The other most visible element on this page is the heading, “Speaking of Pictures…,” followed by an explanatory subhead, “In Paris young lovers kiss wherever they want to and nobody seems to care.” 15)Speaking of Pictures…, Life 28, no. 24 (June 12, 1950): 16-18. The opposite page contains five images, laid out with a minimum of white space between them to maximize their size. Each image is given its own, short caption. The image now known as The Kiss is captioned with the sentence: “This was a short kiss, ‘a kiss rapide,’ says photographer.” 16)Speaking of Pictures…, Life 28, no. 24 (June 12, 1950): 17. The “photographer” is also quoted in other captions, thus adding authenticity to the images. Robert Doisneau’s name, however, appears only once, in the middle column of the small-type body text on the first page of this photo essay.

Life was not directly concerned with changing the social status of photojournalists. But Life featured skillfully crafted and visually attractive photo essays, thus promoting the aesthetic appreciation of documentary image as such. By doing so, Life served as a catalyst for raising photographers’ self-awareness as creative individuals, artists even—something that was not yet taken for granted in the 1950s. But this was just the beginning of a long and laborious process. The general recognition of photography’s creative potential did not arrive overnight, just as the art world’s acceptance of the documentary image. Such acceptance was not possible before a significant shift in photographers’ and photojournalists’ social status that gradually took place during the 1960s and 1970s.

___

This article has been made possible by a support from the US Embassy in Latvia

| 1. | ↑ | Leslie Katz, An Interview with Walker Evans (1971), in Vicki Goldberg, ed., Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988: 359-369), 364-5. Emphasis in original. |

| 2. | ↑ | The phrase “creative class” is used here as a way to describe people who share the conditions, tools, and skills of their creative work, but who do not form a close ideological allegiance such as a “group” does. The phrase “creative class” has been applied to contemporary cultural studies and popularized by Richard Florida since he published The Rise of the Creative Class in 2002. See the most recent and updated edition: Richard L. Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: Revisited (New York: Basic Books, 2012). |

| 3. | ↑ | Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 111. Emphasis mine—A.T. |

| 4. | ↑ | Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 48. See also a historical account of the daily work at the Life magazine editorial offices: Loudon Wainwright, The Great American Magazine: An inside History of Life (New York: Knopf, 1986). |

| 5. | ↑ | Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), 48. |

| 6. | ↑ | Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), 57. |

| 7. | ↑ | Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2 (2016): 146–166. |

| 8. | ↑ | Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2(2016: 146–166), 151. |

| 9. | ↑ | Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century, History of Photography 40, no. 2 (2016: 146–166), 151. |

| 10. | ↑ | “With the gold rush, in December, thousands came out and waited in line for hours. The police, equipped with the remnants of the armies of the International Concession, made only a gesture toward maintaining order. Ten people were crushed to death.” Magnum Photos, Image Reference PAR170018 (HCB1948002W00295/15), available online at https://pro.magnumphotos.com/image/PAR170018.html |

| 11. | ↑ | Wilson Hicks, Words and Pictures: An Introduction to Photojournalism (New York: Harper, 1952), 110. |

| 12. | ↑ | Maria Antonella Pelizzari notes that “no photographers were acknowledged by name before 1959.” Maria Antonella Pelizzari, Photography and Italy (London: Reaktion, 2011), 122. |

| 13. | ↑ | Martina Caruso, Italian Humanist Photography from Fascism to the Cold War (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 130. |

| 14. | ↑ | Peter Hamilton, “‘A poetry of the streets?’ Documenting Frenchness in an Era of Reconstruction: Humanist Photography 1935–1960,” in Norman Buford, ed., The Documentary Impulse in French Literature (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001), 177–219; Nina Lager Vestberg, Robert Doisneau and the Making of a Universal Cliché, History of Photography 35, no. 2 (2011): 157-165. |

| 15. | ↑ | Speaking of Pictures…, Life 28, no. 24 (June 12, 1950): 16-18. |

| 16. | ↑ | Speaking of Pictures…, Life 28, no. 24 (June 12, 1950): 17. |