Interview with Jason Fulford

How do you know when a thing exists? Jason Fulford’s (1973) practice engages in questions that don’t have definite answers. Like playing a game, there’s space for both rules and creativity, and the two things are constantly intertwining. There’s a question that’s put forward and space for each viewer to fill with what they bring to the work.

This August Jason was in Latvia to run the workshop Visual Language: How Pictures Speak To Each Other at the International Summer School of Photography. His show Clayton’s Ascent is up now at the ISSP Gallery in Riga, closing on September 19th. Jason was a 2014 Guggenheim fellow and is the co-founder of the publishing house J&L Books. His work has been featured in several books and monographs, that include Raising Frogs for $$$ (2006), The Mushroom Collector (2010), Hotel Oracle (2013), Clayton’s Ascent (2018) and The Medium is a Mess (2018).

You once said that you make puzzles but they don’t have definitive solutions and they function more like invitations. Can you speak a bit about the way you see your process and work?

I guess this relates to the individual image and sequences. For whatever reason, I want things to last a long time. There are some things I love that don’t last. I’ll do crossword puzzles, I’ll finish them and throw them away. There’s no need to look at them again. Food is like that too, even though I eat slow – a lot slower than my wife. But when I make work or I’m looking at artwork, I don’t want it to be like a crossword puzzle. I don’t want it to be, like, “Ok, I get it, I don’t need to see it again.” It helps if there’s something that is left open and you, the receiver, fill it in a little differently each time. So, if I’m working on a combination of pictures, and it makes me think of the same thing every time I look at it, I’ll break it up.

It makes me think about the concept of language games. In his later works, Ludwig Wittgenstein criticises the Augustinian idea about how meaning in language comes into being. Augustine has an example of a child who learns meanings of things at the moment when someone points to something and says, for example, that’s a box. Wittgenstein asks how the kid knew that the other person was pointing to the box and not the material it was made out of or simply the shape of the object, etc.

He criticises the idea of fixed meaning and draws a connection between the way languages and games work. While you can’t define the universal concept of a game, you can understand what makes it a game by playing it. Your work also finds a balance between something that is movable and changing, and something more structured.

I have about ten answers to that. First of all, about games. I love this line from End Zone by Don DeLillo. It’s a book about an American college football coach and nuclear war. At some point he’s talking to the team, he’s getting them excited for the game, and he says: “It’s only a game, but it’s the only game.” That’s basically my philosophy of life – don’t take it that seriously, but take it seriously because this is where we are.

Oh, and then – “that’s a box.” These last couple of years I’ve also been reading a lot from David Bohm. He was a physicist in the US, he died in the early 90ies. Some of his research was later used for the atomic bomb, but after WWII he started to apply his ideas from physics into philosophy. He talks a lot about how fragmentation with language is artificial but it’s necessary for communication and organising thoughts. He just reminds us that it’s important to understand that it’s artificial even though we’re still going to use it. So, that is a box but it’s also a tree, those are also atoms, it could be a hat or a form, or a metaphor – all sorts of things. I think about that a lot. But it’s one of those things that you can’t think of purely or else you can’t function as a person. That’s an interesting thing about ideals vs actual circumstances. They’re never in sync. But they keep playing off each other somehow.

I like this idea – I think you’ve referred to it elsewhere – about working in-between emotion and logic.

I love that about people – that we came up with the idea of logic, but it’s impossible for us to live purely by it. I think the experience of a situation if it has a mix of emotion and logic is richer because your brain is working on multiple levels simultaneously. Also, within one human being, you can be very logical, but you can also be very emotional. Those are opposites but they both exist in a person. I love that it can happen. You can apply that to all sorts of other situations in the world where conflicting things exist simultaneously, and it’s not a problem.

I think that’s one of the most interesting things about being human, that both A and non-A can exist within us at the same time.

I don’t want to be too heavy on references, but I have to mention Kierkegaard here. Either/Or is one of my favourite books. It’s about a poet and a judge who write letters to each other, and a third person, the editor, who found these letters and is showing them to us. But really all three of these people are the same person, conceptually. At least, that’s how I read the book. I think a lot of Kierkegaard’s work, which is more fun than what I was told it would be, is about that. It’s multiple personalities, but it’s not a disorder.

Now especially with the internet and having such vast access to information and ideas it’s hard to imagine having just one idea or all of it being just about one thing. We constantly experience this multitude where some of the ideas we embrace go against each other.

We’re probably not meant to have this much information. We don’t function that well with it. That really might be what takes us down.

This is probably a coincidence but you shoot on a 6×6 which is also the Instagram format. What do you think about the future in terms of visual literacy?

It’s hard for me to answer that, I’m not an anthropologist or a scientist, and I don’t have any data. I can only really speak for myself. I appreciate a point of view, which is different from an algorithm. I’m interested in the way that a person experiences the world, and when I look at work, I want that to be communicated to me, and that’s what I take away from it. Photography is just the medium for that, just like words are for the writer.

In the beginning you said you don’t want your work to be an easily solvable puzzle. We seem to think that we’re very deep and nobody can understand us, but then algorithms can easily figure out what we want in order to sell us stuff, influence our politics and the way we think. Do you think we’ll reach the point where algorithms will be able to replace creativity?

I got an e-mail from somebody this year who said they got my Raising Frogs for $$$ book, and that it’s great. I thought, oh, what a nice e-mail. And then it went on to say that the person lives in San Francisco and works for a start-up that is using artificial intelligence to do image editing. I wrote back: “Wow, you work for the devil.” And that was the end of our communication.

Yeah, that’s horrible. There’s a great movie called Desk Set from the late 1950ies with Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. It’s a situation like that where Katharine Hepburn works in a picture research library in a corporation, and Spencer Tracy is an outsider who has been brought in to computerise the library. All of these conflicts that this question brings up, exist in that film. It has a happy ending. Let’s hope this one also does.

In a lecture about your work, you kept on referencing back to what you were reading at the time you were making something. How do you think fiction influences your practice?

I love reading fiction. Unfortunately most of my favourite authors are dead. I want to find more living authors that resonate, but it’s hard, I don’t know why. I haven’t found the right ones yet. I guess I love it as a pleasure but then it also goes into your mind as another memory in a way. It becomes part of an experience like a story that somebody told you or you experienced yourself. Great writers, like, Flannery O’Connor, Mikhail Bulgakov, Viktor Pelevin, Joseph Conrad, and others, they’re really talented in having a unique vision of the world and articulating it.

You know how you probably have other photo friends, and sometimes you are out in the world and you see the world the way they do—like one of their pictures, so you take a picture and give it to them. I think the same thing happens with authors – you’re in a situation and you feel as if you’re in that person’s world. Or maybe because you’re reading their book, you’re in that mindset and you see the world that way. That’s great. I really love people and I like sharing these things. I don’t mean to sound silly about it but it’s a serious pleasure.

When reading you’re the one creating the picture and, maybe, that’s why it makes such a strong experience.

Yes. Another example – Alain Robbe-Grillet, a French writer from the 60ies who I love. He was part of a movement called ‘the new novel.’ These writers were trying to put the Balzac-style novel away and start something fresh, just to keep the form evolving. They weren’t saying that ‘the new novel’ was the way it should stay, they just wanted to try something else.

They wrote in a kind of objective way. Robbe-Grillet describes things almost as if he was a camera. You read his descriptions of space that are from a specific perspective without commentary—just description. The effect of it is that you become the character or you melt into the character. And then, when there’s repetition throughout the book, that changes a little bit, you can’t tell if your own memory is flawed or if it’s the character’s memory that is flawed. It’s a great experience of you melding with the book. On the surface the writing seems very cold and photographic, two dimensional, but in reality it becomes an experience and it’s different from the experience of another type of fiction. He’s been an influence on me too.

You have a publishing house – J&L Books. What’s exciting for you when you work on your own books or publish other people’s projects?

So many things. First of all, I love making things. My mom told me that when I was a kid, I folded my clothes really neatly and put them in the dresser as soon as I could stand up, which is weird. I love packaging things into the most efficient type of container or form in a way that you can then unpack into something more complicated. That’s something I love in bookmaking. And this relates to something you said earlier about structure and movement.

One of the things I love about books is that the relationships you determine are fixed and they stay that way, and somebody will find it a 100 years from now and it will still be fixed like that. I love books for that reason as opposed to another medium like an exhibition or a website. Here’s the thing – I can’t say anything as rules, because I immediately find exceptions. Like now, I’m thinking of a book called Iris Garden, that Little Brown Mushroom published a couple of years ago with William Gedney’s photographs and text by John Cage. The whole book comes apart and you never put it together the way you found it, so it’s always changing and that’s part of the concept for that content. But then, I guess, you could think of that box being the structure and those relationships are fixed in a movable way. I love those kind of challenges with a book.

Also, when you work with another artist as an editor, you need to understand how they see things so you can make suggestions that are not you projecting something onto the work but from their point of view. I love that process, and I only work with artists I love, because I work for J&L as a volunteer.

Do you think your education in graphic design plays a part in the process?

It’s hard to separate it out. For example, when I’m doing the workshop here, I try to take complicated ideas that are intuitive for me, and separate them into games, exercises or lessons that illustrate one of those ideas. So there’s something artificial about it. A lot of these exercises I don’t do myself, but I do a version of them in my head, so I’m trying to teach that way of thinking. When I work on a book – content, editing, sequencing and design are all simultaneously going on. I’ve also worked as a welder, carpenter and moldmaker. For me graphic design is just something in the tool-belt. It’s a cheesy way to say it, but that’s how I think about it.

You’re in Latvia now. Have you been taking any pictures here? What do you find interesting in the landscape?

I’m interested in seeing this part of the world, but when I started reading about Latvia I started to wonder if I’m going to the right place. It seems like it might be woods everywhere and I don’t know what am I going to do in the woods. I’ve been working pretty hard since I got here, but I had one free day in Riga so far. I woke up in the morning and walked all day. That was great. But I only shot two rolls of film, 12 pictures each, so I don’t know if this is my place for pictures but we’ll see. Hopefully I’ll have some more time to wander.

You have a show in Riga at the ISSP Gallery. Can you talk a bit more what it is about?

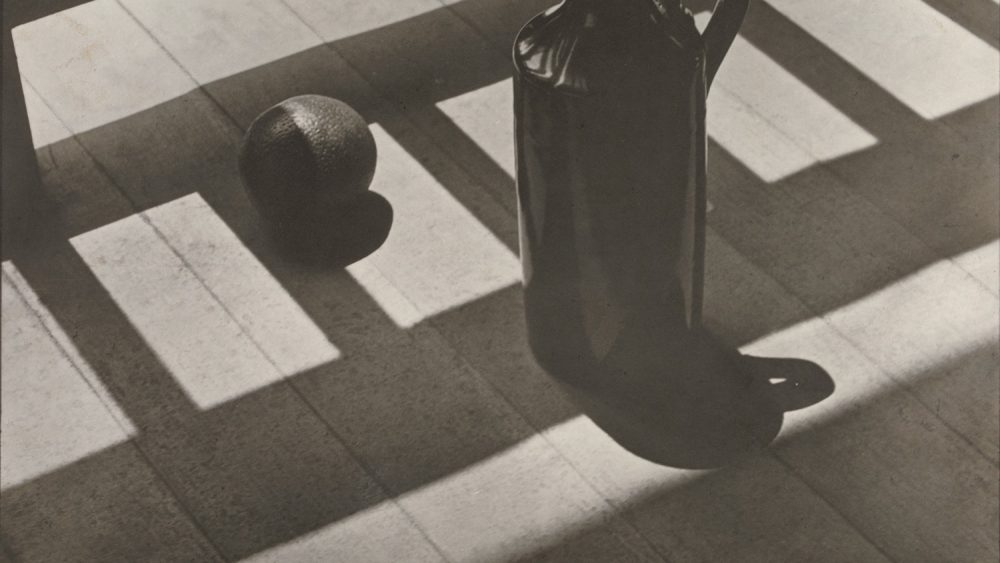

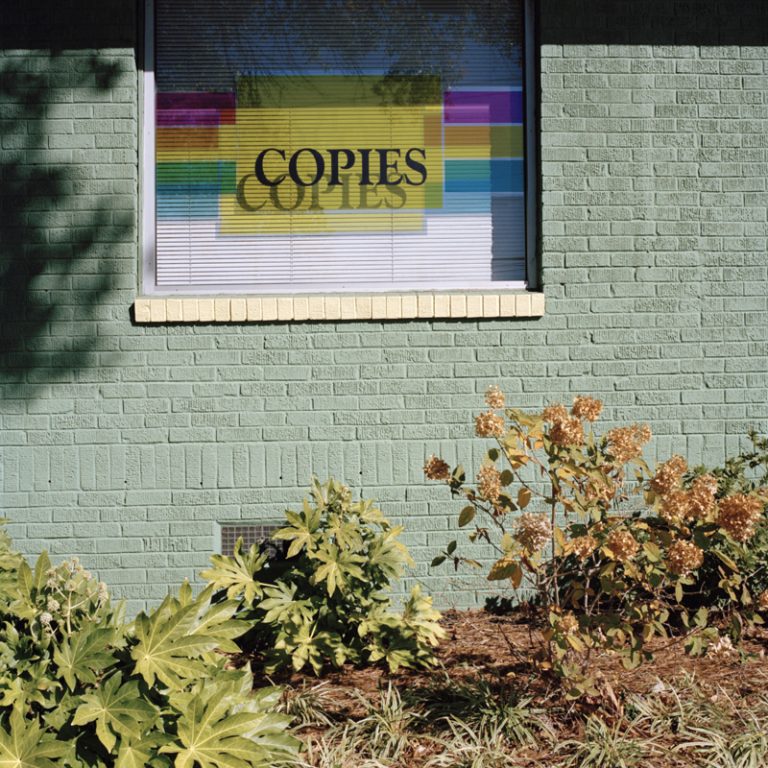

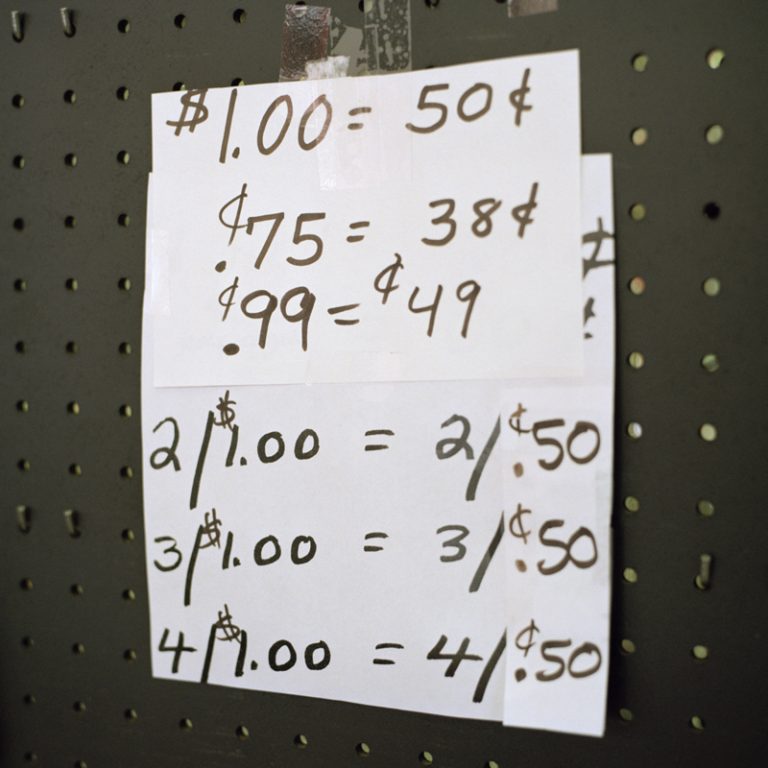

The work comes from a recent book called Clayton’s Ascent. It was published by TBW Books, and it’s part of a series of four books by four artists – Vivian Sassen, Guido Guidi, Gregory Halpern and me. The books have some connections because we all talked about them as we put these edits together, but really they stand alone as separate ideas. When TBW asked if I wanted to make a book, I’d been looking through some old work that I’d shot in the end of the 1990ies and beginning of the 2000s in the United States, and I guess something having to do with 2016-17 made these pictures from almost 20 years earlier rise to the surface. The meanings change as time goes on.

What I found were pictures that were kind of dark content wise but colour wise they were saturated. And that combination was interesting to me in a way I couldn’t really put my finger on. I guess it ends up relating to things that I love and criticise about the country where I live. I have mixed feelings about things and some of the things that I might be critical about, I also kind of love in a weird way. So, for me, if I tell you that much and you go see the show and read the book, it will colour it in a certain way.

The show only has six images from the book, plus some sculptures and a video. We’ll also have the book in the exhibition, so you can see the whole context.

The way you work is that you build a continuous archive that you also look back at. How does that work for you? Isn’t it sometimes hard when your visual language changes with time? Maybe, you get better at certain things but lose other things?

The square actually helps me with that. That’s one of the reasons why I haven’t shifted from it, because they fit together so easily from years apart. The visual language – I think of it more in terms of combinations rather than single images. So, there are always possibilities for that language to evolve.

When I first started making work that I considered good, I had some ambition to get it out there and make things quickly. After I got that out of my system and got some things out in the world, I slowed down a little bit. I started to think about the fact that I don’t want to retire, I want to keep making work until I die. This is another kind of cheesy metaphor, but it’s true – I had an experience looking at a tree trunk and its rings. I was talking to a carpenter about wood. The trees that grow slower, their rings are tighter. Like, maybe it only grows an eight of an inch in diameter every year or so. There’s a lot of tiny rings. A fast growing tree grows one inch diameter every year or more. So, cheap wood is wood that grows fast, but it also breaks easier. Or you put a screw into it and it cracks, but an older one will actually break a screw. You have to drill a hole first and then drill a screw into it.

I started thinking about the rest of my life more like the slow-growth tree. Something like a steady backbeat is this accumulation of pictures. Always looking, observing and saving, and when it feels like the right time to say something with those pictures, then use them as vocabulary to express that. I mentioned The Crack-Up, the F. Scott Fitzgerald book, it was another moment, reading his notebooks, when I understood that as a sustainable method of working. Writers basically have life experience that is their archive that they use. I think when Ernest Hemingway killed himself, it was because he was losing his memory. If you read his last book, Across The River and into The Trees, it’s terrible. It’s super cheesy. I think it’s because he had no real memories to apply to it, so he was inventing them. Actual experience for a certain type of person, like me, is always more interesting than something I’m going to come up with from scratch.

___

This article has been made possible by a support from the US Embassy in Latvia