Details through the senses. Interview with Sanna Kannisto

Sanna Kannisto (1974) is a Finnish photographer. Her passion combines art and science; she takes the knowledge from scientists but uses the freedom of an artist to approach her subjects – birds, plants and landscapes. Lately, she has been interested in the bird gaze and human encounter with it, making the bird portrait a collaborative act. Her photographs are made in a portable field studio, a stage for the bird to perform. Kannisto holds MA in Photography from the University of Art and Design in Helsinki; she has an extensive exhibition experience. Kannisto is the Finnish Art Society’s William Thuring Prize laureate of 2017 and has received a 5-year working grant by the Arts Council of Finland. Kannisto’s works can be found in numerous major museum collections, including the Centre Pompidou, Paris, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, Statoil Art Collection, Norway and Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki. Her latest monograph Observing Eye was published in 2020 by Hatje Cantz.

Are you a full time artist?

Yes, I have now a five year working grant from the Arts Council of Finland.

Have you noticed a change in terms of expectations of the artist or the artist’s profession throughout your career?

I’m now a mid-career artist. When I was still a young artist, there were so many exhibitions and curators wanted to find me. And now this period is gone. Now it’s more of the surviving mode. On the other hand, I am also more established and people already know me. And they have some expectations, as how my work should look like. In contemporary art, it’s strange how quickly you need to have something new.

Everybody always wants you to have something new, even if it was similar to what you have already done. It has become similar to consumer culture nowadays. For example, my exhibition at the Finnish Museum of Photography; we worked together with the curators for about two years to make it happen.

I have made big production works. But now I don’t have any place where the exhibition could go. Or, I have worked so long with the book. I have photographed for about five years, and then the book is in the process and the exhibition is opening at the same time. But then, a couple of months later, people ask what I am doing now. You also have to keep working when you have finished something. For example, I have to keep making Instagram posts of the book to promote, because otherwise it would all be forgotten and wasted. When I had my book done with Aperture, I also had an exhibition in their gallery. Then they were trying to promote it to different places, to have a touring exhibition. I had so much demand to have the exhibition elsewhere, I produced some of the images in four copies, framed and mounted. So you understand that all my money went into the production and some of them are sitting in the storage. I also had a pressure from Aperture since the exhibition was in their storage for maybe one and a half year, so I decided to take it back to Europe. It went to France, to Berlin, and then back to Helsinki. But, of course, then the Houston Museum of Natural Science showed interest in the exhibition. Since it was already shipped back, the conversation ended. They thought it was too expensive to ship it back and forth. What would have happened if I waited longer? They get a big audience in that kind of place. Science museums are even more popular than any art museums.

You started working in Finland and in Europe later, after years in rainforests of Peru, French Guiana, Brazil and Costa Rica. Why did you choose to work with exotic flora and fauna before exploring the native environment?

I was deeply fascinated with the incredible biodiversity of rainforests. I was also fascinated how science explains the world to us. I read that the Turku University had this Amazon project, so for the first two times I traveled with the researchers from this programme. It was also part of wanting to make an expedition with scientists. It is great when you are younger, and you have good energy and when you are kind of naïve, and you don’t know where you are going and how hard it is. Then you start to realize how difficult the work is, and what kind of challenges you face. But when you are younger, you just want to go there.

What were the challenges?

I think it’s very difficult to represent and portray the diversity of the rainforest. Science is facing the same kind of challenges when the environment is so rich. I had so many different approaches to the subject.

Do you have a favorite place where you liked to work most? Why?

I guess it was in Central America, in Costa Rica. It was eventually so easy to go there on my own and to get into the research stations. I could get the artist’s working permit also to collect the species and work together with the scientists. I met some nice people, such as the scientific directors of the stations and they really liked the way I worked. They were really encouraging me.

Can you say you have adopted something from the scientists, working along their lines? Do you also think they learned something from you?

I’ve been following how different researchers do their work. I definitely borrowed some working methods. I imitate what scientists do. But I also wonder all the time what the balance between art and science is, what we can learn when we are doing scientific research, and how it looks when you are an artist, or when you are a common person. You can feel something or you can use your sensory perceptions as well. And this is something that is maybe more pronounced when you are an artist, when you think about your vision, about what you hear, what you can smell, and how you feel. The whole experience is different because science is mostly about measuring and repetition, it has to be objective, and I can be very subjective. I don’t know if they learned anything from me but in Finland, when I was photographing birds in a similar small field studio, the scientists were amazed how quickly the birds were adapting to this space and situation. One researcher has done an experiment with a certain bird species to see how quickly they adapt by measuring the stress hormones from the blood. Most of the birds I photograph, I have them for about 20 minutes. It’s a rather short time, but they are actively studying the studio surrounding, they are curious and some, of course, get the stress reaction. In that case, I release them immediately but most of the time, they adapt quite quickly. They are curious, and they observe me. The title of my book is Observing Eye; it’s about the observing gaze. We think that it’s us, humans, who observe the animals but it goes both ways, especially if there is only one bird, they observe me. If there are more birds then they just observe the other birds, I’m not relevant anymore.

How did it start? Were you always interested in art and science?

It’s wonderful how photography can show things to people and how we can collect things with photography. I’m a visual person. Sometimes, when I look at scientists’ work, it seems so mathematical, so filled with Excel tables. I’m terrified because I feel that it’s something I don’t understand. Science is so specialized these days; they are really limited to one path. In some scientific groups, there are people who go to the field and there are people who only stay in the office and work with the data. It’s very different than what it used to be back in the old days. I feel more like a Renaissance person who can look at everything that’s interesting.

The environment of your childhood and later formative years – was it more art or more nature?

I guess it was more nature. I don’t belong to a cultural background family but just a normal, working class family. We didn’t go to museums. When I was a child, we only went to a summer cottage, picked berries in the forest and went fishing. We had all this great outdoors life. The forest has been a friendly place, where you feel good. Many people in Latin America are amazed [about this fact], they are afraid of the forest because they have no access to the forest necessarily. If they live in cities, it’s a much more distant place to them than to us.

Your photographs are somewhere in between documentary and staged, it’s art and science, portraiture and cataloging. The work is so filigree, minimalistic, it often reminds of a drawing. Have you defined what they are?

I think it’s all that but the basic quality is documentary, I guess. Photography is a tool that shows in a detailed way. I have worked with large format cameras to have all the details and I want to make a big enlargement, large scale works. I want to study the human ways of seeing and working with nature more than I want to claim to make any research on nature. It’s more about how we see, how we portray and how we can represent nature.

After more than 20 years in the field, have you noticed any change how we, humans, observe the nature?

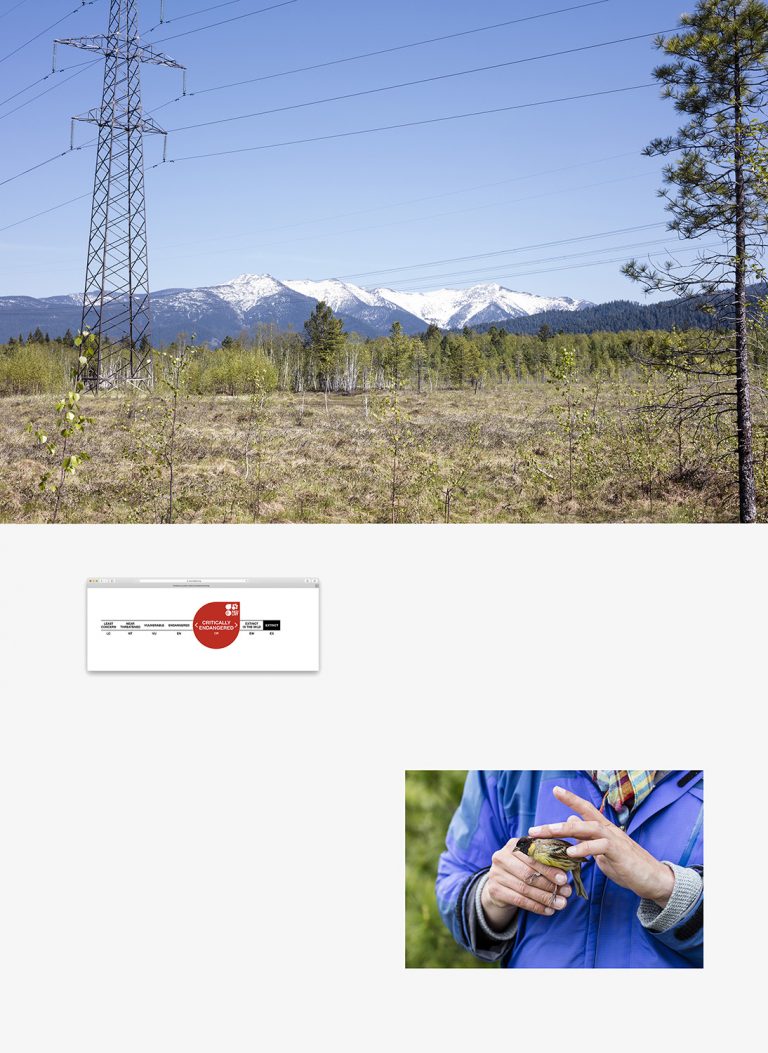

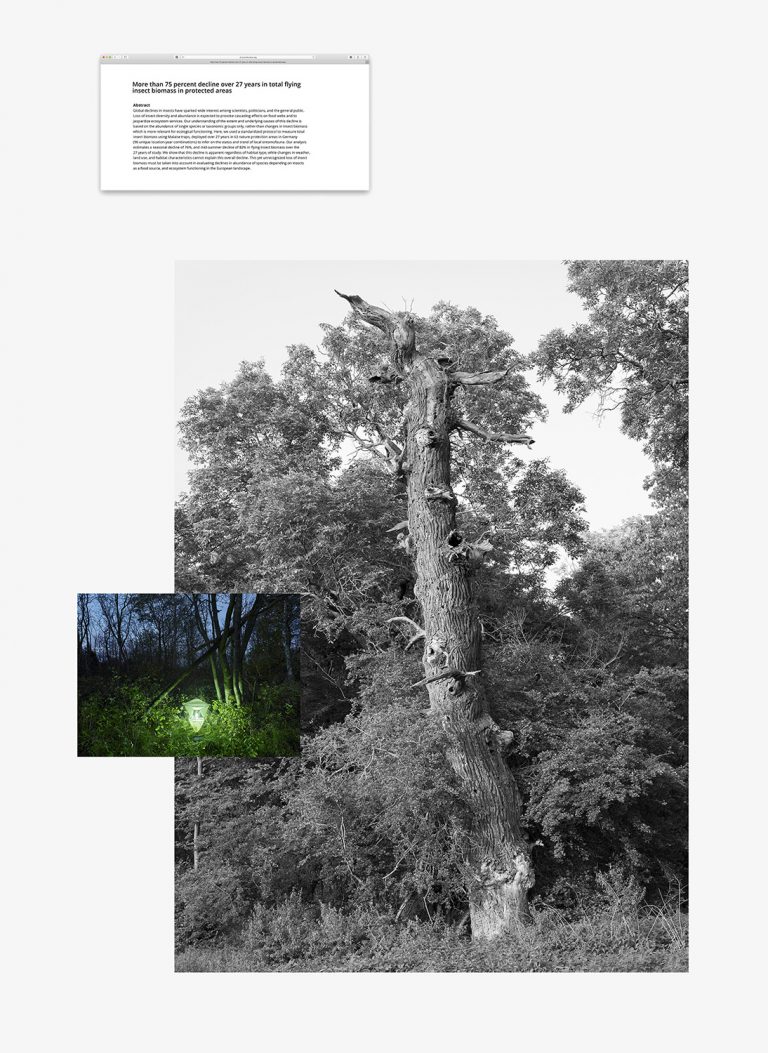

Yes, of course, it’s more political how we talk about nature, for example. We try to value it more. Sometimes we put a price to it. Think about all the endangered species, for instance. People try to convince each other how certain environments are important. In Finland, for example, it’s more relevant now to think about how important the peatlands and the swamps are since we have destroyed almost more than a half of those environments. We have tried to dry them to have more forest growth so we could make forestry. We talk so much about Brazilian rainforests and how they destroy them but we do it also in Finland. We have destroyed all the old growth forests. There is 1 % left in the south and Finland. It’s the same in Europe. I think we should look in the mirror.

Your latest collage work comments on ecological crisis claiming that is more visible than previously. Have these years in the field added to your activism?

My work shows so much the beauty and enjoyment of the birds. They are obviously so elegant and so beautiful, but I feel a certain responsibility for it. When I read about what’s happening to insects, for example, how the amount of insects has decreased dramatically, I want to also shake the viewer to see the other side. There is also this kind of movement in art now that you have to talk about the climate change or something similar. I don’t feel obliged to do that. I’m so happy to see artworks that don’t deal with these issues, because I don’t think it’s the basic meaning of art to educate people. The meaning of art is to stay within the society, to be up to date but you have to find your own personal way, you cannot just glue it on top of your page. However, I think you have to be really subtle with it by finding a way that is good for you, if you want to talk about these problems, but it’s not what art should do.

How much do people form their view on nature through illustration rather than experience?

A lot, you see this when people come to rainforest. For example, they have seen nature documentaries and they have so many expectations when they arrive to the place to see the animals like it was in the documentary. It’s also important that we don’t only show the very best parts of nature to people because in reality it’s not like that.

Why did you choose birds as the main subject of your art?

When I switched from the rainforest to work more nearby, I was thinking of the possible species I could photograph. I have done some mushrooms, butterflies and moths but in Finland we have two snake species and maybe two frog species. In the rainforest, there are like 300 snake and 300 frog species, but birds are a diverse group. There are almost 500 species in Finland. I had photographed some birds already in the tropics. They are also a quite good size for my field studio.

Do you recognize birds by their songs?

I do now, better than before. I recognize different species as well.

The birds often look like studio portraits, and they are definitely very aesthetic. Is that a reference to something unnatural you want to talk about through your art? Or just the opposite, to show the natural beauty we wouldn’t see otherwise, at least, so easily?

There is a reference to portraiture, the way humans are portrayed. And because there is certain interesting aspects about portraiture, if you’re a photographer, what kind of relationship you build with a model. If you get their trust, than you can get some openness in there. And also, if you take a portrait of someone, and you make it two meters wide, it has to be an important person. In this way, I want to highlight the smaller birds or the small species. I want to put them on a stage for everybody to see them.

How collaborative are the birds?

It’s really a mystery. I don’t know, what they are, what they are thinking but it’s also the thing that is very interesting to me. I can see certainly when the bird is curious, observing, flying around and sometimes even looking at the materials of the studio. If I have to move something, my hand comes in from the side, something they are puzzled about. And then there is the way we look at each other. Sometimes I feel that the bird is really concentrated to look at me, but I can’t tell what’s really on their mind.

Can you talk about your process? How do you get ready for the fieldwork? What is the post-production process like?

I work together with scientists and volunteers who do the ringing. Birds are captured with the mist nets. I have picked beforehand a collection of different tree branches that I could use and when I get a bird, and I don’t necessarily know which bird is coming, then I have to just select from what I have. When I have the bird in the studio, I first look how the bird is behaving, moving, I just stay calm and observe. Then, if the bird is okay and moving, I put on the flashes, I have about 8 to 10 small flashlights. The studio is outside, so the bird can hear the sound of other birds or the sound of wind, or the sound of the leaves moving in the wind. Sometimes they hear another bird or a group of birds comes to wait for the bird who is in the studio and they vocalize. After I have photographed the bird, I might photograph again the branch or some other branches of the same tree, so I can change it in the post-production if I want that. I now photograph more branch variations than before, because I have learned that I always need some more pictures. I feel completely free to do that because it’s not a documentary. In nature photography, I have just learned, there are a lot of rules that you cannot do but it’s not the case in art. I can use everything that the photographic medium can offer to my benefit of the artwork.

Your hand holding a bird in the picture, some landscape and still life images, your portrait in the field, props from photo shoots shown in the exhibitions – I love these details in the work that you place among the images of birds or other specimen. They add to the project, making it even more encyclopedic. Are you looking to portray the subject as wide as possible?

It was in the Sense of Wonder exhibition at the Finnish Museum of Photography last year that we decided that we want to show the stands of the labs, and the branches. There has been some demand to show documentary about how I work. I understand it; the process is interesting to me as well. Sometimes the process can be even more interesting than the result. It’s nice to think how I can show that.

In 2019 you added bird videos to Observing Eye. They are interesting to watch – even if they are with the same props and with the same backgrounds, the movement and sound change so much. Can you comment on the reasons for choosing to make video works?

It’s exactly what you said. It’s about showing the situation. Sometimes, after seeing my work, people say that they really liked my drawings. That kind of drawing would be a repetition of natural history drawing. That’s why it was important to show the movement and live birds, and you can also see that the birds are doing well. They are moving and vocalizing with others.

You showed this movement through photography in the book Fieldwork that you made with Aperture. There are pages of birds, mimicking the flying movement.

Yes, the hummingbirds. It’s really interesting how movement is stopped – that’s something you cannot see at all with your eye. And also how the bird movement is challenging the picture that it’s almost always out of the frame.

How did you choose the length of the videos? When I was watching them, I was wondering if the length is corresponding to the time that the birds spend in your studio but then you said that they can be in there for 20 minutes.

No, the birds are often outside of the frame, they can be at the bottom of the studio or flying in the net that connects the studio and the camera. If I showed the whole 15 or 20 minutes, then the bird would be in the right spot for only about four minutes, the rest of the time we wouldn’t see the bird at all.

So what are you working on now? And is there any subject that you would like to work on that you haven’t yet?

I’m starting something new but I haven’t really got there yet, so I don’t talk about it. I will also still continue working with the birds, trying to go into a new direction as well. It’s always hard to decide when it is a good moment to start something new.

Has the pandemic anyhow changed your work?

With the pandemic, I have missed all the chances to show my work at foreign art fairs. The book publisher also was not in the book fairs. I think I even cannot know exactly what I have missed but I certainly understand that there are missed opportunities. Even this autumn, if there are art fairs or the next year if everything begins normally, then, in a way, my book is already old. So many more new books have come out in the market in the meanwhile.

What’s the favorite part in your artistic process?

I enjoy working in the field. Then I, of course, enjoy when I get things ready. But, for example, the computer work is not that nice. However, it’s good that there are so many different tasks.

Where do you find your inspiration?

It’s from art to science. It can be any scientific information or a study or other artist’s work or, even the history of photography, or the still lives and the cabinets of curiosities.

What is the most beautiful surprise that nature has offered to you through your work?

It’s all the small details. I always look at the things from a close distance rather than the whole landscape, the details are the most intriguing. But it’s also the mode that you can turn on when you are working in the field. Even if there are some hectic parts in the work, it’s still relaxed and nice to work in the nature. When I lived in the rainforest, I was always there for two or three months. It was nice when it became everyday life. On the first year, you can think that you are a traveler for the first two weeks. When it becomes like a normal everyday, then it’s something I really enjoy.