Photographing the unfinished. Interview with Andrew Miksys

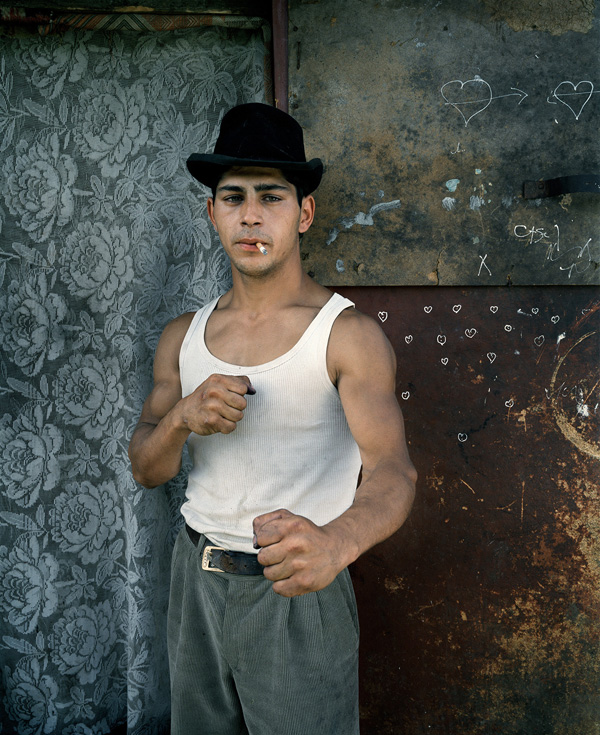

Originally from Seattle, Andrew Miksys is an artist living in Lithuania. He has published several photo books, such as Disko (2013), Tulips (2016) and most recently Bingo (2021). We meet on Zoom a couple of days before Miksys’ exhibition BAXT is about to open at the MO Museum in Vilnius. “Baxt” is a Romani word that means ‘luck, fate, destiny’. The exhibition engages with the Lithuanian Roma community – a minority with very little voice and often the subject of hateful stereotypes. Miksys’ photographs go beyond the prejudice and capture a more intimate reality of the Roma people in Lithuania. The exhibition BAXT at the MO Museum in Vilnius runs until 14 August.

Your exhibition BAXT is opening at the MO Museum in Vilnius this week. Tell me a bit more about the project and the show.

It’s a project about the Roma in Lithuania. I’ve been working on it for 20 years. I came to Lithuania on a Fulbright grant in 1998 to photograph. I didn’t really know much about Lithuania and I just walked around. I was in Šnipišķes, which is a very old neighborhood in Vilnius, and I met some Roma people – that’s how the project started. In 2007 I made a book of the project, but then I just kept photographing and it kept growing. I planned to do a second edition of the book, but the pandemic started. Hopefully by the end of this year I will be finished with it.

There are a lot of pictures from Vilnius, but there are also many small towns and villages in Lithuania where the Roma live. I actually live in Vilnius and also in Žagarė, which is right on the border with Latvia. Many Roma families live there.

During the 20 years you’ve been working on the project, have the conditions for Roma changed in Lithuania?

I think it’s kind of similar to everybody else in a lot of ways. There are a lot of things that happened. Many people left. They went to the UK for work. Most of the people I know that went to the UK have done pretty well. There were always these questions about stereotypes and prejudices against Roma people here, but in the UK I think they felt a little bit freer.

There’s all of this effort for more integration in Lithuania, which can be good and bad. People want to hold onto their traditions, but then what happens when those very, very old traditions conflict with the contemporary world? Some things have gotten better and some things have gotten a little bit worse.

As I understand BAXT was supposed to be shown in an exhibition a few years ago, but the show was cancelled last minute. Now it’s being shown in MO – a museum that opened a couple of years ago in Vilnius. Can you talk a bit about what happened?

In 2018 I was working with the National Library of Lithuania to show this exhibition. It came down to writing a publicity text about the exhibition. They asked me to write it, so I did. I thought it was quite good. One thing I talked about was that the Roma and the Jewish Lithuanians were persecuted by the Nazis and that some local people helped the Nazis kill Jews and Roma because of their ethnicity – no other crime, just their ethnic background, their race. The Roma had been fighting for many years to have the Roma Holocaust day made official in Lithuania (it’s on 2 August). At that point, it was not yet certified as an official day. Jewish Lithuanians have had that official day for 30 years.

So I wrote just two sentences about that in the text and the Library didn’t like it. They sent me the text back, had highlighted those parts and asked me to take them out. I said I wouldn’t, but I also said that I don’t care, don’t use the text – write it yourselves. They cancelled my exhibition. I really thought it was censorship and I talked about it in public, on Facebook. Then I sued the Library in court because after I had talked about it on Facebook, they published my text online without my permission. It went all the way to the Supreme Court, which rejected my case.

The basic lesson for me was that Lithuanian institutions still have problems dealing with issues that are difficult in Lithuanian history. The Library didn’t know how to deal with the history and the issues of minority groups, like the Roma, so they cancelled the exhibition. My partners were the Roma community and they could have called them and said, we have this problem with Andrew’s text, let’s work on it, let’s fix it, but they didn’t. I think it really showed that they lack the sensibility to deal with an exhibition of this kind of subject.

But the MO Museum, where I am having a show now, has been extremely good. They had worked with the Roma community for the last seven months; they went and filmed people from the community talking about their experiences and the history. I think it’s a really great opportunity for me and my photography, but the idea is to use my exhibition as a way to talk about the Roma community today and what is going on. For me that’s the exciting part – to have other events related to the Roma community.

A lot of your photography deals with political subjects. How do you see the relationship between art and politics?

What’s interesting in Lithuania, is that history is unfinished. Latvia, Lithuania – they’re young countries. In a way, of course, they’ve been around forever, but they’re still figuring out their history. As a photographer it makes for an interesting place to photograph. For me it was just exciting and interesting at first. I didn’t realize that the things I was photographing touched on these political elements or things in Lithuanian history that are sensitive. I didn’t set out to do a political project. They were interesting subjects. You can’t work on something for twenty years if it’s not personally interesting.

The political things that came out as I was working on this project or on my other projects, wasn’t the intention, but in a lot of ways I am very happy about it. I do projects to have discussions. The photo world is very small and sometimes the discussions aren’t that interesting, but when your projects go outside of that world a little bit, it’s very interesting. I think it can be important in Lithuania especially because it’s kind of uncomfortable. There are still very negative views about the Roma and Jewish people in the media.

If we’re on the subject of politics – I wanted to speak about your project Tulips. It’s work that you made in Belarus before the 2020 election happened. It was also shown here at the Riga Photomonth in 2016 and you made it into a book. How you think about these images now in the context of what is currently going on in Belarus?

Watching what is happening in Belarus is a real tragedy. I have very close friends [there]. I showed that project also in Minsk at the Y Gallery of Contemporary Art in 2017. The Lithuanian Embassy helped me transport my photographs to Minsk with a diplomatic car and show them there on Victory Day. It was a private contemporary art center and the guy, who owned it, has been in a KGB prison for over a year and a half now. You have to really think what it means for Belarusians to make art, to make photography – it’s life and death at this point. That is so scary. I feel quite helpless because I was hoping my book would help explain Belarus, but then it just reached the fulfilment of how horrible Lukashenko can be.

Twice now I’ve had a great opportunity to photograph Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. I photographed her for The New Yorker a couple of months ago and last year for Bloomberg. She’s just an amazing person. She keeps working every day. She’s great to talk to. Her husband is in a KGB dungeon prison. Every day she has to think about that. I know Latvians and Lithuanians understand the situation, but the thing to do is to explain to other people in other countries in Europe and the US how serious it is. It’s a European country that is living in a horrible authoritarian state. It’s hard to watch. The border is only about 35 km from Vilnius and it’s just a different world.

Regional politics are getting more and more tense at the moment.

I think that the stories that are told in this part of Europe are very important to photograph. People elsewhere don’t realize how democracy can disappear. Wars can happen. My mom is Ukrainian. Democracy – you take it for granted, but it can disappear. I’m American and we are also now fighting similar issues in politics where democracy is threatened. We have to remind ourselves and everybody how important it is to fight for it.

And Lithuania, of course, got its independence, joined the EU and NATO, and it seems like everything is great. But when my exhibition was cancelled at the National Library, it was kind of a reminder that sometimes institutions go off the rails. The leadership can start censoring artists. This was at a library where you’re supposed to have discussions. The politics of what happened to my exhibition were kind of scary. I started to think, what’s next? Look at Poland, which is our neighbour, and they’re firing directors of museums and libraries and installing people who do what the government wants them to do. It’s more serious here than people think it is.

Yes, we’ve seen a rise of populist right-wing politics in the last few years in Eastern and Western Europe and in the US.

In Poland the right-wing government started by going after the Holocaust, saying you can’t talk about the Holocaust – you can’t say Poles helped the Nazis kill Jews. That was a law they passed. When you start to see minority groups being vilified or history being changed, I think that’s when it gets a little bit scary. When my exhibition was cancelled and the Library said, don’t talk about the Holocaust, I started to get very nervous that this kind of politics is coming here as well. It’s not quite like that yet and my friends would say that it’s no big deal, it’s just Lithuania, but when you see the real consequences in Poland, Hungary, Belarus, it made me think more about those things.

On a lighter subject, I wanted to ask you about your books. You’ve self-published all of your books with your publishing house ARÖK. Why do you think it’s important to make books at a time where most things happen on a screen? And why self-publish?

I self-published my first book in 2007 and that was the moment when things were starting to change a little bit. As a younger photographer I really wanted to do a book. I went around to publishers and they liked what I showed, but they never wanted to publish it. I decided that I would do it myself. It’s kind of cool that in Lithuania there’s good printing for good prices, so I was kind of lucky I was living here and I wanted to make a book.

The photo and art world has changed a lot since I made that book, but there are these “gatekeepers”: the publishers, the galleries, the museums. And I got to a point where I thought that if these people don’t want to show my work, I’ll just do it myself. The reason I want to make books is because it’s a great way to show people the way you want them to see your work. It’s like making a movie – you edit the book, you sequence the photos, you choose the paper, the cover material; I get a bit obsessive. I make puffy books with plastic logos and stuff. That becomes the really cool part – you can make this object that you can send around the world and somebody can hold and sit with it quietly, and see your work. That’s why I like that experience. Of course, it’s one thing on the computer, but sitting down and feeling the paper, the cover material, all those things, I think it’s important. It’s the end point of my projects. That’s what I want. I make a project so that I could make a book that I can show people, and I can show my work in a way that I want it to be seen.

The book format also fits photography projects well, better than some other media.

Yes, and – we’ll see what happens after the pandemic – but the great thing about photography is that there is this whole world of photobooks and book fairs. I was invited to the New York Art Book Fair. I went and had a table. People from all around the world come to those events, buy your books and have discussions. It’s really cool.

And self-publishing in photography is actually a good branding thing to do. I know from my friends who are writers that if you self-publish your book it means that you’re not a very good writer or that you haven’t been accepted by the literary world. In photography, I’d say, it’s cooler to self-publish. Especially at a book fair. You have your table and everything is laid out the way you want it to be. You’re presenting yourself.

I also wanted to ask you about your collaborations with the fashion designer Gosha Rubchinskiy and the brand Vetements. They’re both pretty famous for making the post-Soviet aesthetic cool. There is a similar allure to photographs from your series Disko — tracksuits and an Eastern European working class look. What were the collaborations like?

The stylist and collaborator for both Gosha and Vetements was Lotta Volkova. She’s from Russia, but has lived in Paris for a long time. She bought my Disko book in Paris and then sent me an email wanting to do a project together. I had to ask my wife what is Vetements.

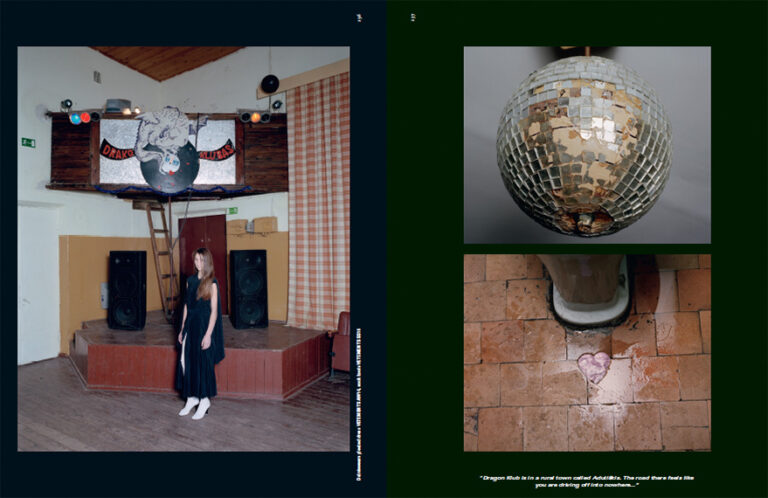

Lotta was very serious. I’ve done fashion shoots before with street casting, but in the end they’ve never really wanted to use real people. But Lotta was insistent, she said she wants to go with me to the discos, and we’re gonna ask the kids there. At that time, about five years ago, a lot of the discos had already closed. But there were two that were still working. So Lotta came to Vilnius and we went to these really remote discos in the middle of winter. She’s an artist. We found these kids there and it was the first time where I felt like it wasn’t like some job, but that it was a real collaboration. It was about making interesting pictures. That was quite cool. I didn’t feel like I was doing commercial thing.

With Gosha, it was for Dazed. I went to Moscow and I photographed his stuff. I had met him before. Both Gosha and Lotta said something about this too, but the “post-Soviet” thing, the terminology, I don’t like it. It connects everybody to this Soviet world. I know they use Soviet symbols [in their work], but it’s using them in a new way. I don’t know if it has worked totally, but at least they were trying to do something. I like that.

I guess Vetements, their thinking about fashion, has changed the rules of the game a bit.

For me that was quite cool. Because it was really an art thing. Lotta is not someone who is hired to do some styling. It’s her life. She’s gonna make it the way she thinks it should be. I really respected that and her background was originally in photography.

It’s nice when you get hired to do something and they actually want you to do it in a way that you think it should be done. I’ve done some fashion shoots before and it gets so watered down – it’s not really you and you wouldn’t put your name on it.

Gosha is pressing these buttons. There was an USSR Adidas shirt. Everybody here thought Gosha made it, but I don’t think he did. The Lithuanian foreign ministry got upset about the t-shirt. There was all of this controversy, but I don’t know… In the fashion world they’re obviously trying to be provocative, but I think for young people it’s also about ways of getting away from that history too.

Your show is opening in a couple of days. Besides this exhibition, what are you working on now?

I spend a lot of time in Žagarė. I’m photographing a little bit there and working on some projects. And with the exhibition at MO, the big thing is to make it into a book. Make a second edition [of BAXT] with all of this new material.

It’s been hard to photograph during the pandemic. My main thing is people and I don’t feel safe. I’m triple vaccinated and I always wear a mask, but I don’t feel comfortable going to somebody’s house and trying to photograph them right now.