Journey into the unknown. Interview with Georgs Avetisjans

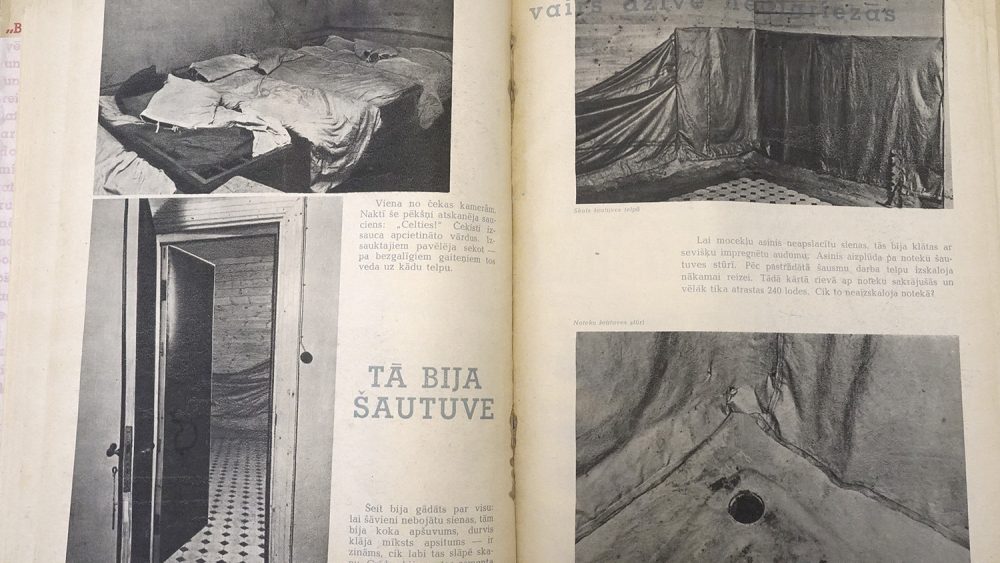

Through August 2nd, the Railway Museum will host an exhibition by Georgs Avetisjans (1985) titled Motherland: Far Beyond the Polar Circle. The opening will also mark the launch of his book with the same title. This body of work is deeply rooted in Georgs’ heritage. On June 14, 1941, his grandmother was deported to Igarka, where she spent 15 years, and it is also the birthplace of Georgs’ mother. After extensively studying the available materials in the archives and preparing himself physically and mentally for this endeavor, Georgs embarked on an unknown journey to the northern regions of Siberia. There, he discovered warm-hearted people and encountered the breathtaking beauty of nature, which stood in stark contrast to the horrifying events of the past.

Georgs Avetisjans is a photographer and bookmaker who obtained a master’s degree in photography from the University of Brighton in the United Kingdom in 2016. He also studied under Andrejs Grants and participated in several ISSP summer schools, the Docking Station art residency in Amsterdam, and other international programs. Georgs is a member of the European photography platform Parallel. He has received multiple awards, served on various expert commissions, delivered guest lectures, and his work has been published in international media. The series Motherland: Far Beyond the Polar Circle has been exhibited in group shows in Switzerland, Luxembourg, Italy, Sweden, Lithuania, Poland, and Portugal. He founded the publishing house Milda Books, in which his previous book Homeland was released in 2018.

How long were you preparing physically and emotionally to start the project Motherland. Far Beyond the Polar Circle?

The idea was born quite some time ago, but I seriously began considering it in 2017-2018. That’s when I started planning and creating a concept and a plan for how to proceed. The planning involved communicating with people connected to the Arctic polar circle, learning what to expect, how to connect with the people in that region, and how to prepare for the climatic conditions since I traveled there in winter. Everything was new and unknown. I knew one person, a former colleague from Yakutsk, who also shared valuable information with me. In 2019, I started researching and gathering materials at the Occupation Museum and the National Archives. That was the practical part, but the moral and emotional preparation involved reading literature and delving into history, which was quite intense, especially when the war in Ukraine had already started. It was disconcerting to see history repeating itself. I recently read about it as ancient history, but now I see it happening in the present. Currently, I feel a sense of satisfaction because I see how the entire process has come together and culminated in the book and exhibition.

Did you obtain any information from your family?

I had very minimal information from my family. When I started working on the project, my mother was still alive. Unfortunately, she passed away in 2020, but she did share some things with me, although not much. Some of the information I discovered in the archives was also new to my mother. For example, I thought that my grandfather was exiled from Smolensk, but it turned out he was actually deported from Johvi, Estonia. How he ended up there, no one could explain. My uncle is still alive, and he believes that after Smolensk, grandfather moved to Vladimir, where he studied and worked, and due to his work, he was sent to Estonia. He was exiled because someone didn’t like something about him. During that time, there were repressions against the Russian people as well, not just the Baltic people.

Did you encounter any problems during your research and while making photographs?

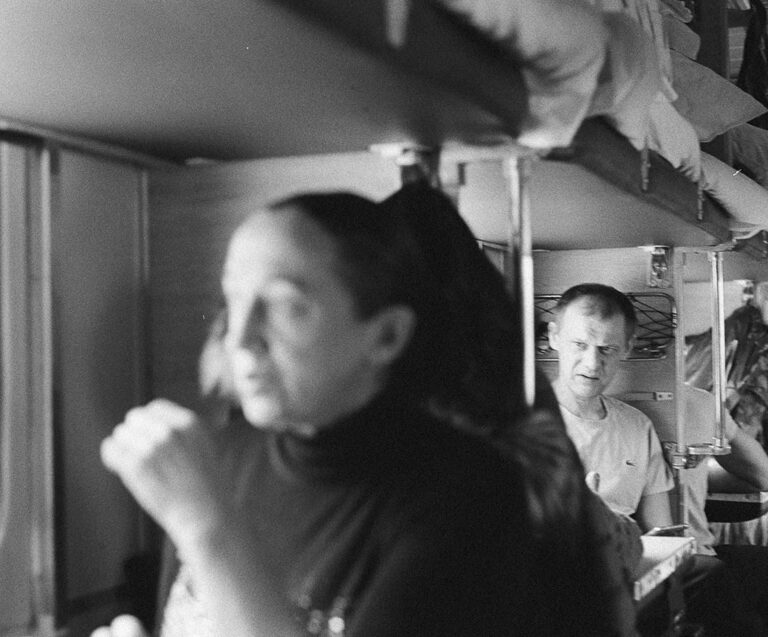

In terms of photography, I faced technical issues because I chose to work with a Soviet-era Salut camera. It was a deliberate, conceptual decision. One of the problems was that the shutter would get stuck, and I couldn’t rely on the mechanics, so I had to manually advance the frames. Another issue arose due to the climatic conditions, as condensation would form when transitioning from -30 degrees Celsius outdoors to indoor environments. It made it impossible to take photos for an hour or an hour and a half, but during that time, I had the opportunity to establish a connection with the people I was photographing. I also had other cameras, like an Olympus, which I carried on my chest to capture candid moments. The Salut camera was mounted on a tripod, and the frame was staged. The book and exhibition also include images taken with a smartphone, documenting the process. If the Salut camera is visible in any of the frames, it’s documentation captured with the phone. I didn’t even realize at the time that it could be included in the book, but when putting it all together, the documentation of the process organically fit in. The research process never truly ends and adds a different presence through the camera. In the video works, you can hear my voice off-screen. The book is designed in a way that when viewing all the materials, the viewer becomes a researcher as well. However, speaking of challenges, not everyone agreed to be photographed, so I had to find ways to establish a connection and gain their consent. Overall, these may seem like minor issues because before the trip, I anticipated encountering more problems.

Was it also easy to find archival materials? Are they all from Latvia?

In Latvia, even accessing the archives was not easy because I needed to prove my relationship with my grandmother. On-site, it was only possible to take photos with a phone to later review them at home. Scanning was done by archive staff using a special scanner, but it came at a high cost. I selectively chose what to scan. Overall, I’m very pleased that such materials are preserved in the archives. In Igarka, I was fortunate to establish a personal connection with the archivist working there. She allowed me to scan until late evening, even though her work ended at five o’clock. She also urged me not to mention it to anyone, as I had to go through a lengthy bureaucratic process to access the archives. In the department of vital records, there was a law enforcement officer, and I had to prepare many documents to obtain the information I was interested in.

Was it already clear during the process that the book will be the primary result?

Yes, because this book is part of a trilogy. When I started the project, I thought about the form it would take, using similar elements that would connect it to the other works in the trilogy. But I didn’t know it would be in a box, or that I would use archive materials. All of that unfolded during the process, as it is a journey where answers emerge. When I was asked about this project in Igarka, I said that primarily it would be an exhibition, as the project was running at the same time to my participation in the PARALLEL residency, where the curator and I were creating an exhibition. But even then, I already understood that the project would be bigger because I’m interested not only in history but also in the present, the community, and dreams of the future. Taking into account the current context, in the book, in collaboration with translators and editors, we have also included footnotes to help Western readers understand that much has already happened. The influence of propaganda in Russia is so strong that ordinary citizens cannot bear the responsibility. Only some individuals of our generation, mainly in Moscow, approach things critically. The residents of Igarka depend on television. I grasped many answers after returning because I gained a greater understanding of what is happening in Russia.

Motherland closes the trilogy in the research process about your family. Nevertheless, is there a following project?

Actually, this is the second part of the trilogy being published, with the third part still in the development stage. Initially, the second part, The Crane that Flew over the Fatherland, is about Armenia, the Caucasus, but it is more complex due to its vast territory. The project focuses more on the diaspora and the deep, intricate and rich history of the Armenian people. Therefore, I lean towards making this, the final part of the trilogy, more poetic. It would explore the diaspora in Latvia, Georgia, and Armenia, hence the crane symbol that flies, and other symbols. While the first parts of the trilogy balance between the poetic and the documentary, here the emphasis will be more on the poetic aspect. I have a substantial amount of material, but there is still a process to go through before the publication. In 2017, I created a dummy of the book, but there is still work to be done before the actual book is completed. Kaltene and Igarka have borders, it makes it easier to work. Art is about simplifying materials through an interesting method, bringing complex content to a comprehensive format. For example, in this book, there is correspondence with an aunt who lives in America, providing her perspective and interpretation of history through a Western lens, through stories from my mother and grandmother about their experiences in refugee camps in Germany. It is a personal communication that is used in the book, offering a different approach to understanding history.

Who are the people in your photographs?

These are the native inhabitants of Igarka who have remained there since the times of deportations, as well as those who have arrived in the recent past. It was very interesting for me to listen to these different perspectives. What fascinated me the most was that the Russians who arrived in the recent past perceive Igarka and its surroundings as a romantic place, as if Siberia is like Paris in Europe. The only difference is that when we usually are disappointed in Paris but they don’t get disappointed in Siberia, they are fascinated by it. There is a dual nature to it because as the author, I am aware of the dark pages of history, and I try to reflect both the historical aspect and also acknowledge that nature is not to blame for the decisions people made within the regime. If you disregard that, you can also see the romance. For example, taking a night walk in the moonlight at -30 degrees Celsius, with the snow crystal clear, and the vast Yenisei River opening up before you. If there’s a chance to get back to a warm room and get a good night’s sleep afterwards, you can perceive this place differently. But if you realize that people were simply discarded without food, surviving on herbs, and not knowing what the next day will bring, it’s something completely different. When a young man tells me that he’s happy that I came to explore my roots, to experience their romance, I have to respond that not only was that not my goal, but I never even thought it could be interpreted in that way.

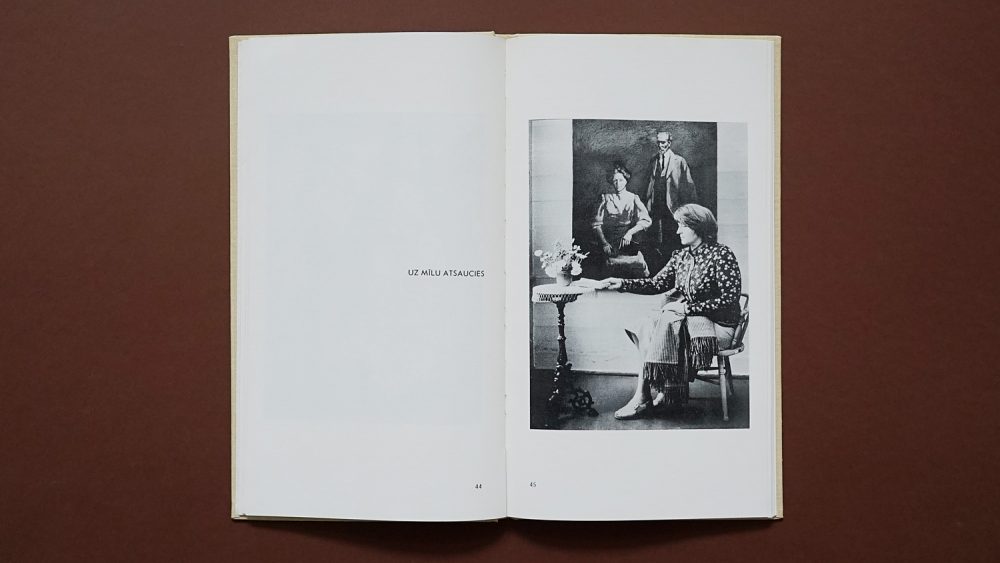

Does anyone still peak Latvian in Igarka?

No but I was able to meet people who have Latvian roots. People who are aware of their identity can say simple things like “labdien” (good day) and “paldies” (thank you). There are people who share that, and it will be readable in the book. There is one woman whom I photographed in Riga, and we had a fantastic interview. She moved to Latvia in 1993, and she understands and speaks Latvian, but our interview was conducted in Russian because she could express her thoughts more precisely in that language. Interestingly, in the background of her photograph in her Riga apartment, there is a painting with a view of Igarka, the Yenisei River, and she is holding a toy as a symbol of lost childhood, as well as wearing a cross around her neck. Regardless of what life she has had, Igarka is still a part of her life. The book also includes a poem by Anatolijs Taureņs and a hyperlink to his reading. This poem is relatively provincial, but it carries a sense of strength and self-assurance. In it, one can feel both Taureņs’ roots and the place where he lives, that this place is accepted as home.

Have you taken interest why the Latvians who stayed there never returned to Latvia?

Some felt that Latvia didn’t want them, that Latvia had betrayed them. Others knew that their homes in Latvia had been completely destroyed, and regardless of whatever else, there was stability in Igarka. Even my grandmother, after meeting my grandfather, who was of Russian descent, wasn’t entirely convinced that someone would be waiting for her in Latvia after 15 years, or if she would have to start everything from scratch again. However, the pull was stronger, and she made the decision to embark on the long journey once again, this time to her homeland. Interestingly, after Stalin’s death, Igarka and the northern regions of Siberia developed, and life there was quite prosperous, so many people decided to stay there.

Did you find the place where your mom was born?

I found that street, Proletarskaya 39, but there’s nothing there, just an empty street. It’s the old part of Igarka where very few buildings remain. Most of them were destroyed by a fire, and many houses collapsed because of the perpetual frost; they simply became uninhabitable. Today, life is concentrated in two microdistricts, in concrete high-rise buildings where it’s warm. I was fortunate to find a photograph of my family house in the Igarka archives.

What is the role of photography in this project that combines archival materials, interviews and video?

The photograph depicts modern-day Igarka, the present time. The rest serves as supplementary material that adds to the narrative of the present. Overall, this is an interdisciplinary project. The exhibition at the Railway Museum serves as an expansion of the book, providing a different experience through video works, interiors, and space. In terms of time, working with the archives and text took more time than the photography itself. The selection process was also time-consuming and complex. Thanks to the Kickstarter campaign, I started writing a diary, and during the process, Kārlis Bergs, who is part of Milda Books with me, suggested that I use it. Therefore, this diary will be available as an additional publication accompanying the book.

Who had the idea to make the exhibition at the Railway Museum? Is it symbolic?

While working on the project, my primary focus was on creating content, thinking more about the book and less about the exhibition. In 2019, when I set off on my journey, Nora Austriņa, who was the curator at the Railway Museum at that time, invited me to exhibit. The museum was interested, but Nora left her job. I enjoyed collaborating with Katrīna Jaunupe from “Mākslai vajag telpu” (Art Needs Space) when we worked on “Atstatuvums” (Separation/Closeness), and I mentioned to her if she would be interested in curating my exhibition at the Railway Museum, which, in my opinion, perfectly aligns with my project.

How emotional was the long journey to Siberia? What interesting stories did you hear along the way?

Of course, it was emotionally intense. I deliberately reread Valija Kampiņa’s diary. She was deported together with my grandmother, traveled in the same train carriage, and upon reaching Siberia, they lived in the same house. I made notes of the places where my grandmother was mentioned. In a way, this diary is also a part of my grandmother’s experience, and during my journey, I had deeply emotional feelings. While traveling, you inevitably reflect, but you also want to be present in the here and now, in our time. At each station, I tried to get to know people, photograph them. I was like a possessed person documenting everything because I didn’t know what would be useful to me from all of it. The greatest contemplation and concerns, even fears, arose when the moment approached to board the plane in Krasnoyarsk, crossing another bridge. It was about -14 degrees, the Yenisei River wasn’t frozen because of the hydroelectric power station and the enormous crystalline moisture. The wind blew in my face, and you could feel the crystals hitting your skin, creating a sensation of your face burning, a bone-chilling tremor. I couldn’t understand how I would survive in the north, but in reality, temperatures of -30 to -35 degrees didn’t feel as cold as -14 with the humidity. And, of course, the unknown factor of going somewhere where no one familiar is, not knowing what awaits me there. I traveled with the thought that I might not even return. No one had gone there in winter. Dzintra Geka goes with a whole team for a short time in the summer, but I went in winter, to an unknown place, to unknown people, for an extended period. I didn’t know what or if I would bring anything back. When I was already on the train back to Latvia, I was very happy.

Did you find what you were looking for?

I think I found answers, largely through archives in Latvia. One of the documents I hadn’t thought of using was the medical record of my grandmother’s first husband, where everything is described dramatically. But in the context of the war in Ukraine, this document seems significant. During the process, I realized that it had been even more difficult than I had imagined. Simply incomprehensible. How many people there were who survived. Those who were deported faced a harsh fate, but it cannot be compared to those who were convicted and sent to labor camps, where they were tortured and ultimately shot. Those who were already extremely weakened and vulnerable, starving and sick, were simply sent to another camp – a camp for the weak. It shocked me completely. Utterly cruel. I tried to find a balance between the pages of the past and the present.

What surprised you during this long process?

I was surprised by how responsive and warm-hearted the people living in the northern part of Siberia are. My mother’s twin brother, my uncle Pēteris, said, “Why would you go to Igarka? Only convicts live there!” I had imagined that I would be visiting criminals, but the people turned out to be kind and welcoming. When I mentioned that I had come to find my grandmother’s house, where my mother was born, they became even more compassionate and treated me almost like a family member. The initial impressions people have about a place can be misleading, so to speak. The first impression of something doesn’t allow for any judgment.