Stories that deserve to be heard. Interview with Claudia Heinermann

Claudia Heinermann (1967) is a photographer from Germany. She graduated from the Enschede Academy of Fine Arts in the Netherlands in 1991 but later became increasingly interested in documentary photography and furthered her studies at the Fotoacademie Amsterdam from 2004 to 2006. Since then, Heinermann has been working on long-term documentary research projects, mostly focusing on various historical and political issues of the 20th century. Her 2015 book, Wolfskinder: A Post-War Story, was widely acclaimed and awarded.

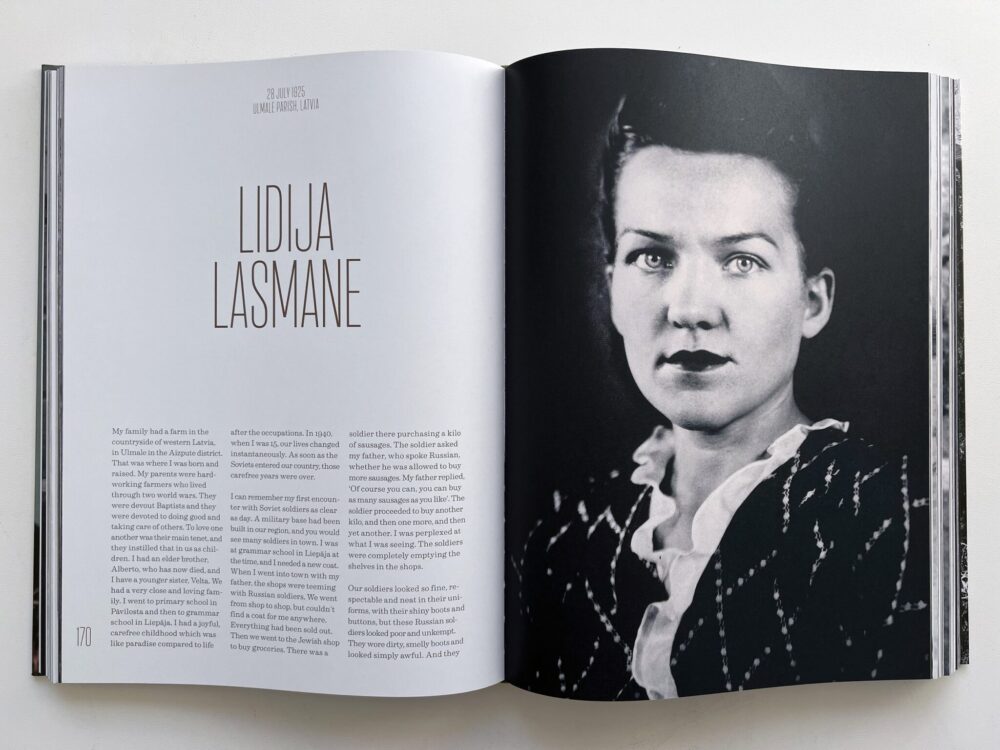

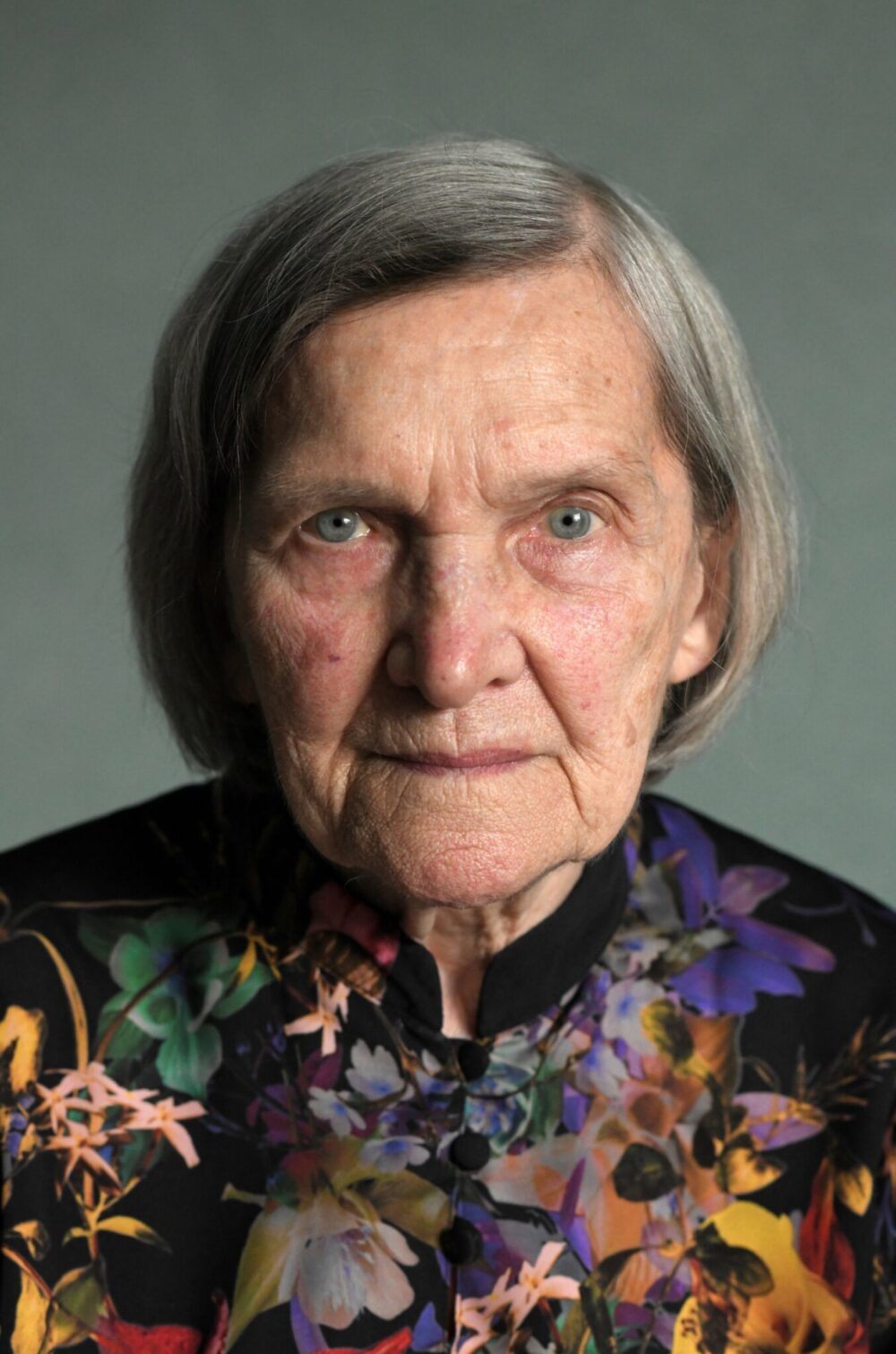

Since 2016, Heinermann has been working on a massive project on the deportations to Siberia, focusing on all three Baltic States. Siberian Exiles is a trilogy of photobooks. The second part, Freedom Fighters, was recently presented in the Baltic States, and a meeting with the author took place on 27 March at the National Library of Latvia. This part includes stories about eight Latvian freedom fighters: Ernests Rudzrogs, Biruta Rodoviča, Hilda Miezīte, Imants Grāvītis, Jānis Zemantis, Lidija Lasmane, Marta Vuškāne, and Mihalīna Supe.

The book Siberian Exiles – Freedom Fighters was created over many years. What was this time like? What was the process of creating the book?

Siberian Exiles – Freedom Fighters is the second part of a trilogy. When I started my research for Siberian Exiles in 2016, I read books on the topic and visited museums and archives in all three countries. I was overwhelmed by the horrors I learned about and by the scale of the deportations that tore so many families apart and that have left deep wounds and scars in society to this day. Honestly, I felt ashamed that I and most others in the West knew so little about your history. That motivated me to start this project because I think your history should be a part of our collective memory as well.

In the beginning, I had the idea to make one book. But there were so many stories that deserve to be heard that I decided to make a trilogy, which is structured chronologically. Part 1 is about the first mass deportation in 1941, the second part is about the resistance against the Soviet occupiers, and the third part is about the second mass deportation in 1949 and the start of the Cold War.

I tried to get in touch with eyewitnesses and interviewed and portrayed them. Most of them I visited many times because they had so much to tell. Every time we saw each other, the trust grew. As a result, the conversations became deeper, and it became easier to talk about very vulnerable or painful memories. Based on their stories, I traveled to Siberia and Kazakhstan in search of traces of their history. These trips were incredibly impressive. The elderly local population remembers the deportees, and they themselves also have terrible stories to tell about the oppression under Stalin. In addition, it was impressive to be in such an extreme climate. This brings you closer to the subject.

While I was working on this project, I asked myself what is important to tell a Western audience about your history? For me personally, it was important to explain to my audience that the Baltic states were independent countries with their own culture, language, and identity. That the Baltic states were occupied against their own will and that they were eager to defend their freedom. And that brought me to the Freedom Fighters.

What I also want to mention is that the interviews with the Freedom Fighters became more intense after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Old wounds were reopened, fear, anger, and fighting spirit resurfaced. It was repeatedly pointed out to me in the conversations that history is now repeating itself. Past and present seemed to merge. Therefore, the book is dedicated to all freedom fighters, then and now. I want to express my deep respect to everyone who fought and fights for independence, freedom, and democracy.

The entire trilogy is designed by Dutch photobook designer Sybren Kuiper.

In your creative work, you deal with a variety of difficult historical and political themes, including very tragic human fates. How did your interest in these topics come about, and why is it important for you to talk about them?

The question of where interests come from is always difficult to answer. But there are two reasons in my personal life that might be the source. I was born in Germany and moved to the Netherlands when I was 18. My parents died young when I was a child, leaving me in emotional survival mode for some years. Luckily, I found my way to become a happy adult and fulfilled life with my own family. My own life experiences make it easier for me to access heavy topics. I understand that language and can empathize well. The fact that I was born in Germany has influenced my view of history. It made me feel responsible to learn from history, to understand what happened in the past so that we can better deal with the present. I am extremely interested in how we deal with our past, as individuals but also as a society. I am eager to contribute, preventing us from making the same mistakes over and over again. I think the combination of these two personal ingredients makes me interested in history and personal stories. History is not one thing but consists of all separate personal stories. We learn to understand history by hearing and empathizing with these personal stories.

My personal short statement: “No one has ever been convicted of the crimes against humanity the Soviets committed. In Putin’s Russia, Stalin’s past is again being brushed under the carpet. That is why it is so important to me to preserve the stories which were hidden from us behind the Iron Curtain. They need to be heard to contribute to a correct historiography.”

How do you regain your emotional balance after working with such difficult stories?

I can deal with that quite well. I usually feel very privileged to be able to have such compelling and relevant conversations with eyewitnesses. These people are usually strong personalities, true survivors who are also very inspiring. Sometimes the stories are very intense, and tears flow from the eyewitnesses, from me, or from the translator; that’s all fine. When an interview is over, we come back to the present, we drink coffee together, eat something, and we laugh and chat with each other; that is also important. As an interviewer, it is relevant to understand that you do not have to carry the tragic life stories on your own shoulders. You listen, you feel and empathize, and you have the responsibility to pass on their life stories in a respectful and sensitive manner. In addition, as a photographer, you have the task of finding a way to tell these types of stories in a visually exciting and interesting way. After all, you do not want to frighten your audience by the weight of the subject but rather arouse interest and invite them to look deeper. It is important to preserve their stories for future generations.

What are your impressions of Latvia and its people?

I really love Latvia, but also Estonia and Lithuania. What strikes me most is that there is a fairly strong solidarity because of the past. People are proud of their country, of their independence that they fought for and that unites them. People are proud of their culture. For example, the Song and Dance Festival. You see girls with green-dyed hair in traditional costumes, which I find impressive. In our country, traditional costumes are old-fashioned, and young people would never show themselves in them. But in Latvia, it is a part of identity, and that moves me. I also find the vast forests and nature incredibly beautiful. Latvia is simply a beautiful country.

Last year, Latvian photographer Georgijs Avetisjans published his book Motherland: Far Beyond the Polar Circle, which is also about the Siberian exiles. Are you familiar with it? If so, what are your impressions of it?

I absolutely love Georgij’s book and also supported his crowdfunding campaign last year. It is particularly beautiful that it is a personal search for his grandmother’s story. It is a tribute to her but also to all others who were deported to Siberia. It is an honest book that was made with a lot of care and love. I really like the shape of the book, with all documents, small letters, and KGB files printed in original format, and I really like Georgij’s photography.

What inspires you?

Nature inspires me the most. It may sound a bit out of context, but in nature, I recharge, and all my senses are energized. Nature is the most positive and healthy source where my mind can unfold, and ideas develop. I also find strong women from history or art and culture very inspiring. And of course, all these hidden stories in history are inspiring and challenge me to dive into them. Life in itself is inspiring; there is too much to mention…

Siberian Exiles – Freedom Fighters has been a monumental work. What are your future creative plans?

I have an ongoing project on genocide in Bosnia that I would like to continue working on. However, I also have plans for a new project that I want to pursue in the coming years. This project focuses on the green zone along the former Iron Curtain and the history of the border that traverses 24 countries and covers a total of 12,500 km. In June, I will commence the project in the Baltic states.