Stabbed in the Eye with Artificial Intelligence

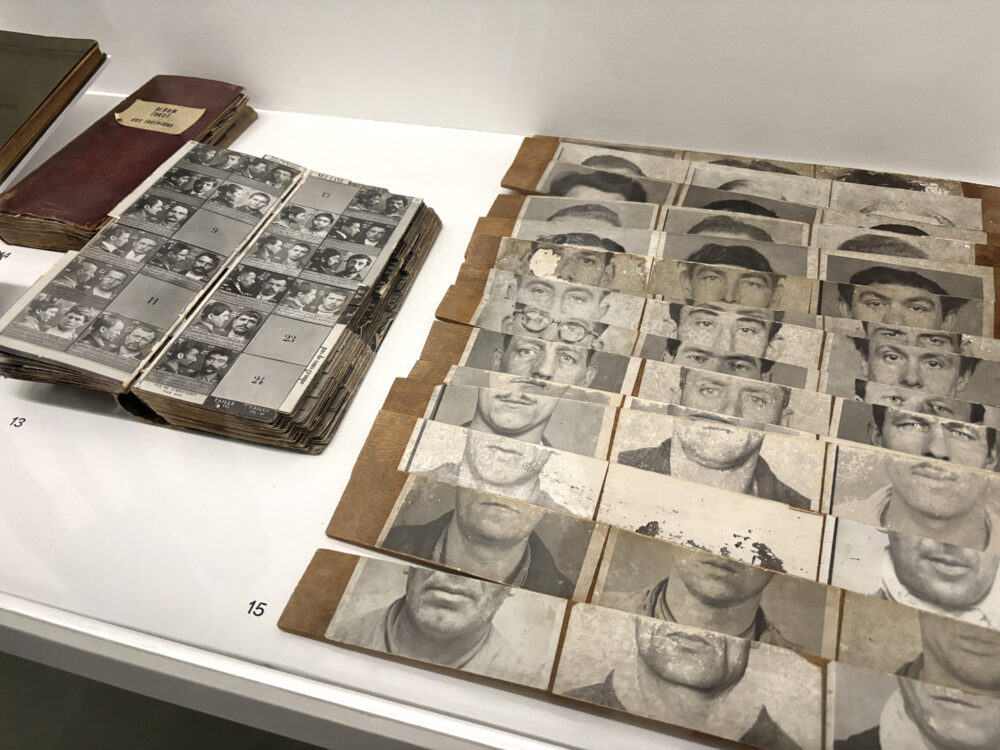

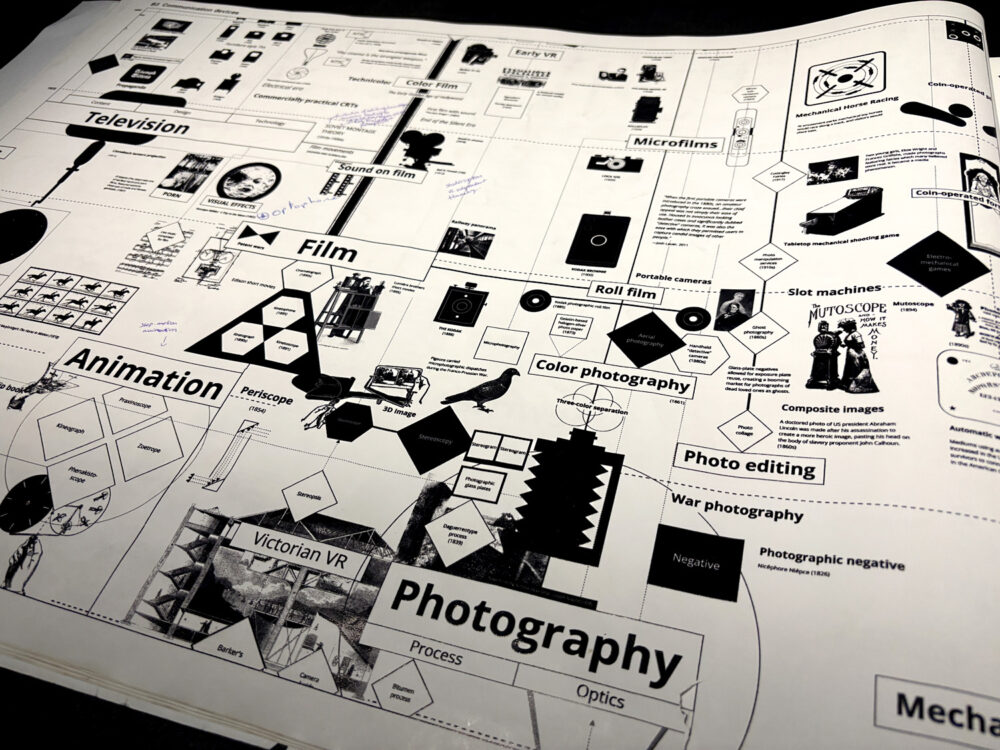

At the Jeu de Paume art centre in Paris, until 21 September, the exhibition The World Through AI (Le Monde Selon l’IA) is on view, where 30 artists reflect on how artificial intelligence (AI) is changing visual culture, control, society, and our relationship with images. The exhibition is truly vast and impressive, spread across several sections in the art centre’s many halls, and it aims to provide a comprehensive perspective, ranging from history to contemporary challenges. These thematic blocks—such as generative AI and latent space, AI cartography, collective intelligence, photorealism, words and images—are occasionally supplemented by display cases, or “time capsules” as the curators call them, showcasing prehistoric technologies (various devices, diagrams, books, etc.) that influenced the development of AI. The exhibition design resembles that of a museum show with an academic approach to an ancient phenomenon—kind of looking back and structuring facts rather than an artistic experiment with new technologies.

Jeu de Paume is usually a venue for major photography exhibitions, and at first glance one might assume this show focuses on photographs generated by AI tools—so-called “promptography”—but it does not. There are no works here that merely project the author’s imagination or aesthetic pursuits. More than that, this is not strictly a photography exhibition, even though photography is closely tied to AI and visible in every room. Rather than celebrating AI as a new creative tool, the exhibition critically examines its infrastructure. Although divided into numerous thematic sections, two central issues run throughout: ecology and power.

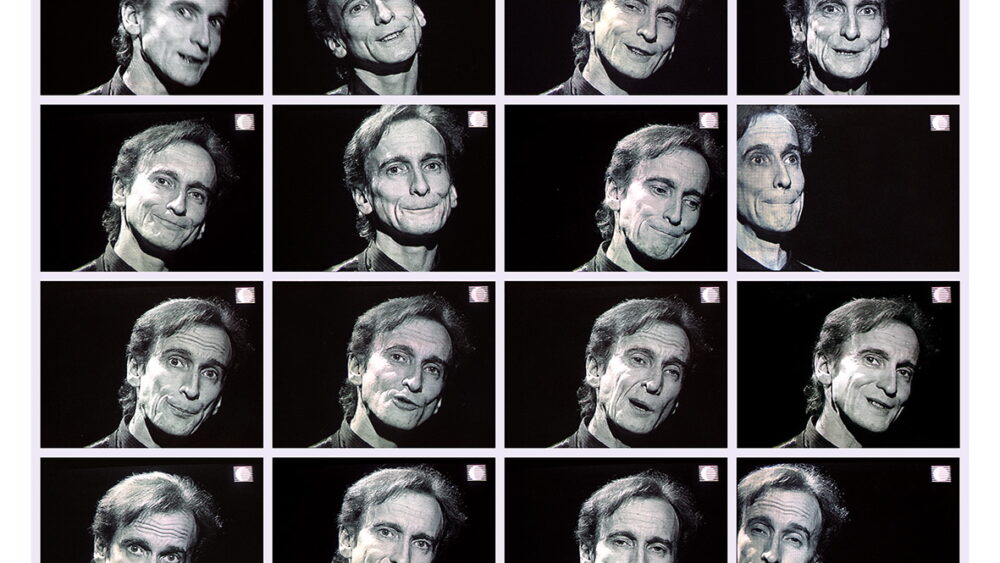

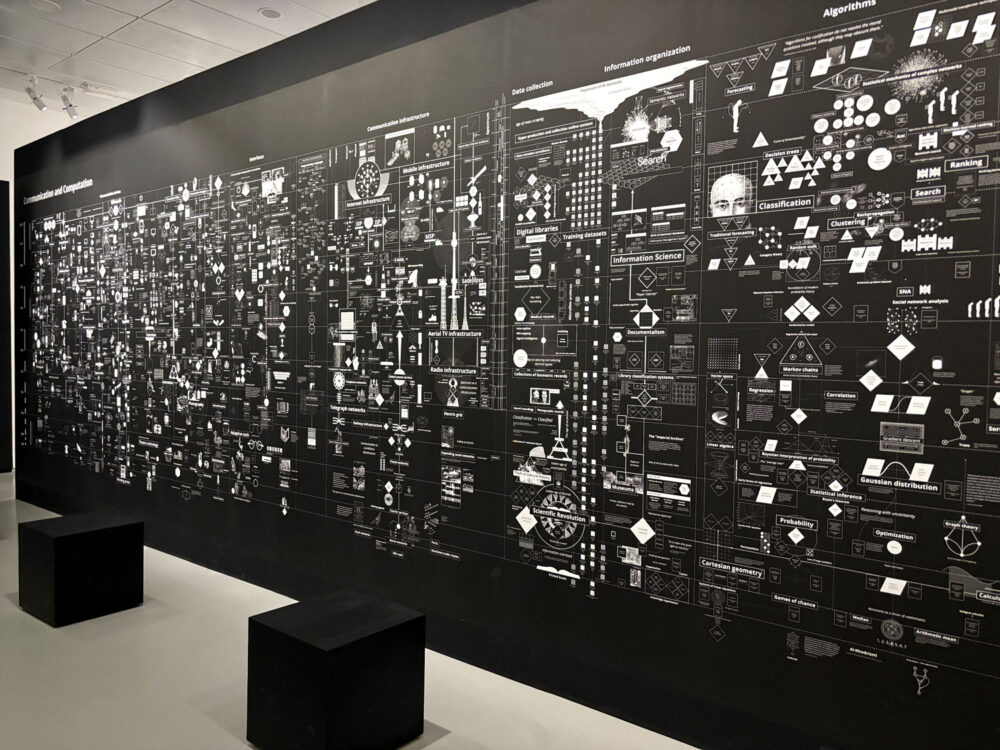

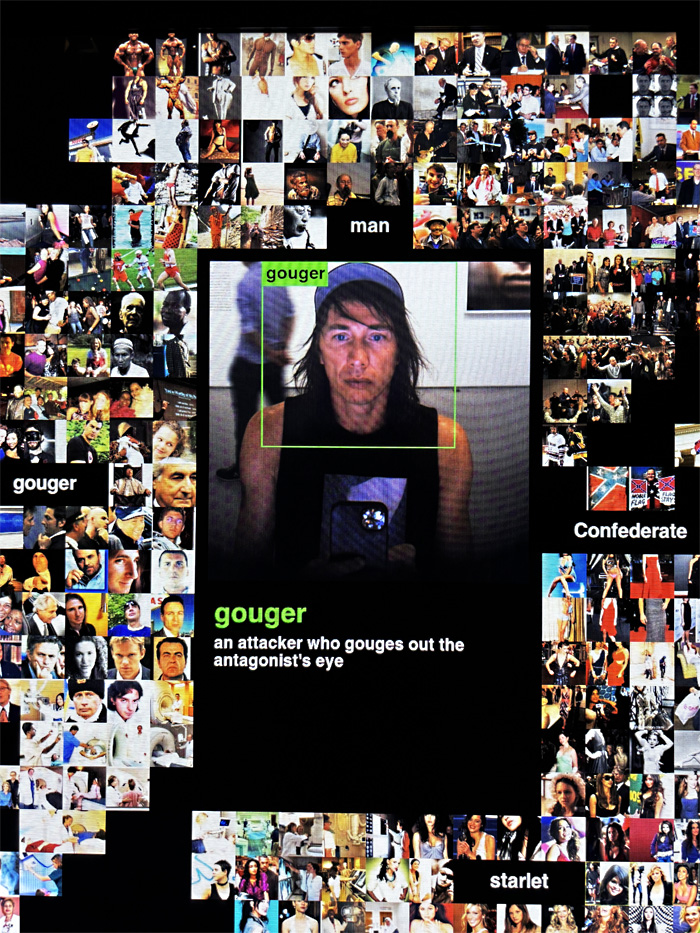

On power—few people still harbour illusions that AI is not expanding its control over us all. Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s monumental diagrammatic work Calculating Empires compares the operations of contemporary technologies with the traditions of colonialism, militarisation, and classification. Where empires once held the power to draw maps and classify human physiognomies, today it is done through algorithms and data infrastructures. There are many other works highlighting how AI tools are stereotypical, sexist, and racist. My own project Latvia via AI in 2023 also reflected how narrow and stereotypical AI’s perception of Latvia is—mainly portraying it either as a post-Soviet shithole or a country where people in national costumes burst into folk songs in every life situation. In Kino Raksti, Alise Zariņa’s interview with curator Antonio Somani also repeatedly circles back to AI stereotypes. One of the exhibition’s two interactive works lets visitors experience misclassification first-hand: Trevor Paglen’s Faces of ImageNet, where a “hidden” camera analyses a visitor’s face and assigns categories. Zariņa was labelled a prostitute, while I was identified as a “gouger”—an attacker who gouges out the antagonist’s eye. I recall once reading that in the US people have even been wrongfully sentenced to death because AI misidentified them as criminals. This exhibition reminds us that photographic images are instruments of power—used to classify, monitor, discipline, and convict. In essence, AI helps sustain existing social hierarchies or create new ones.

Greek libertarian Marxist economist Yanis Varoufakis warns that AI heralds the rise of new types of empires, which he terms “cloud capitalism” and “neo-feudalism”. Whereas past empires relied on shipping routes, colonies, and military power, today’s centres of power are digital platforms and data infrastructures that control access to markets, information, and human experience. These are no longer states and territories, but corporations and their ecosystems in the data cloud, which not only collect and monetise our data but also create new dependencies, turning us into digital serfs living under the laws of platforms.

The biggest surprise in the exhibition comes from works dealing with ecology. People once assumed that AI was an immaterial tool, some kind of cloud of algorithms, but this exhibition emphasises the opposite: data storage and processing take place in energy-hungry data centres, consuming vast amounts of water and electricity, increasingly pushing major tech companies towards nuclear power. This is most evident in the work of Polish artist Agnieszka Kurant, who often uses visual metaphors (such as stones). It is understandable—AI is still relatively new, and its ecological footprint is not yet phenomenal, but it is clear that it is only a matter of time before we start saying that not only smartphone production or car driving damages the planet’s biosphere, but AI as well. The more tightly our daily lives intertwine with AI, the more helpless we shall be without it—and the harder it will be to disconnect from the intelligence in favour of fresh air.

Finally, what about photography in the context of this exhibition? Photography is present, but mainly as an instrument of power—beginning with physiognomy, criminology, anthropometry, and extending to biometric data and algorithms. In the AI context, photography is no longer merely the creation of an image, but a tool to model reality, structure data, and define the future. And, of course, the ecological footprint of AI, and of images it generates will become increasingly relevant. Fourteen years ago, Erik Kessels created 24hrs in Photos, addressing the overproduction of photography: a room filled with a massive heap of 350,000 photos, the number uploaded to Flickr in a single day. It is said that today around 95 million photographs are uploaded to Instagram daily. In March, statistics showed that AI tools were generating 35 million images each day. The question is—where will all this end up, and how will it be used against us? For this visual abundance that we create and consume simultaneously becomes a training ground for algorithms, a mechanism of classification and control applied to ourselves. If AI is commonly seen in two ways—as either civilisational progress or regress—then this exhibition encourages us instead to open our own eyes, so as not to become uncritical consumers, slaves, and idiots.