The Bosnian Identity

Sixteen years after the end of the conflict in ex-Yugoslavia ten thousand humans, who simply vanished into mid-air, are still missing. The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) has been working non-stop, ever since 1996, with the intent of identifying the missing persons who disappeared during the armed conflicts, thus contributing to the development of an appropriate commemoration of the victims. The discolored photos, identity cards, crumpled bank notes are all fragments of humanity buried in time. Every year hundreds of human remains are identified and on July 11th, the anniversary of the fall of Srebrenica, all those bodies are given back to their relatives. Following the ethnic-cleansing operations of the Serbs, in the Srpska Republic now live about 1.4 million inhabitants, of whom about one million are Serbian Nationalists. The Bosnian refugees have never gone back to their homes, many for the fear of finding themselves living next-door to the slaughterers of their loved-ones, others for the lack of a true process of peace: in fact, justice has not been carried out in the most part of the atrocities committed during the war in ex-Yugoslavia.

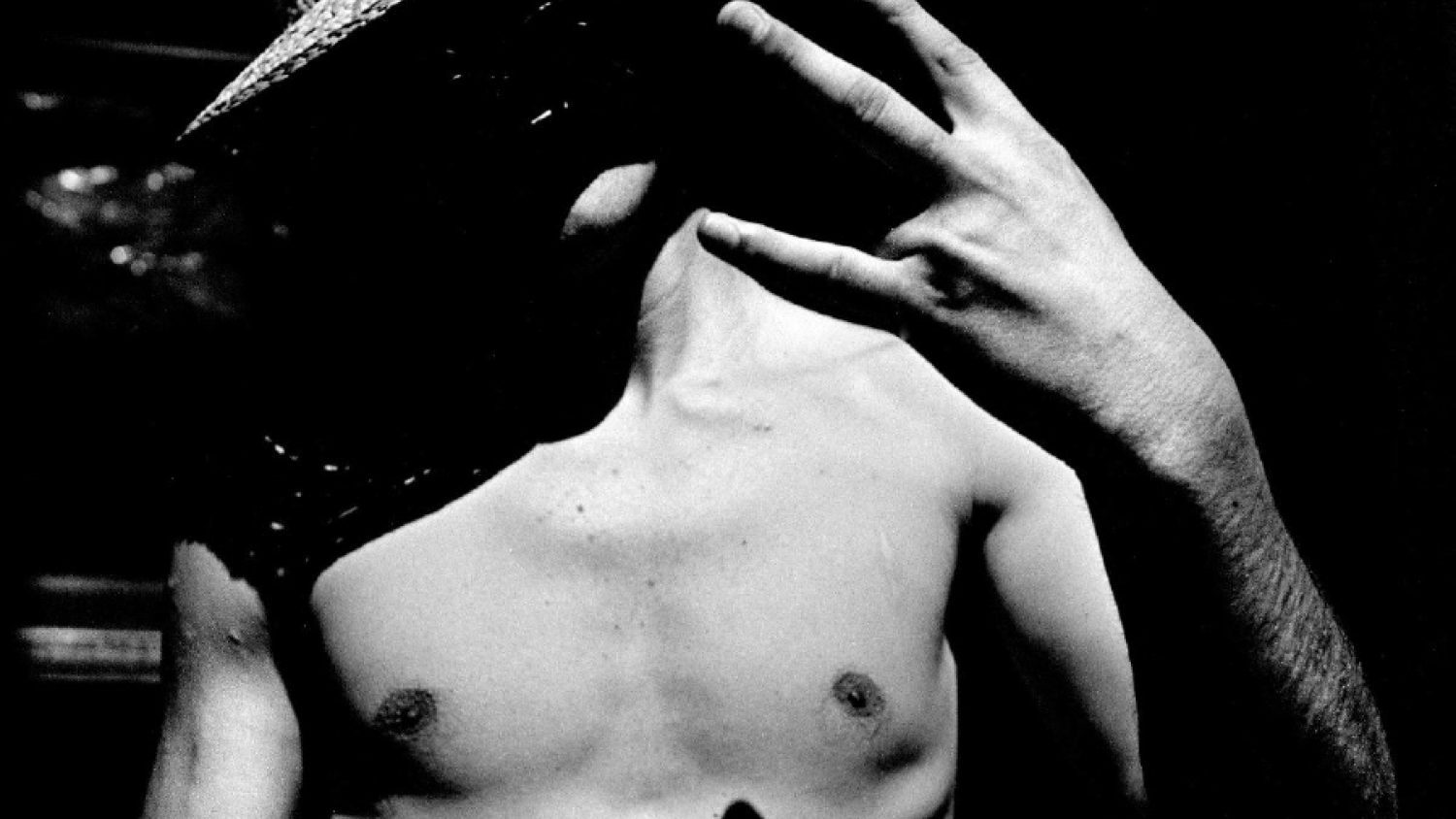

It hasn’t been easy growing up in Bosnia. Children there have had to grow up quickly. They have had to struggle to survive. A lots of youths see their future rather black yet some have decided to stay: Nihad, Tarik, Sucur and the other “members of the gang” who live on the streets in Sarajevo. The rules of street-life have taught them that they can only rely on themselves. Many of them have been, more or less willingly, influenced by the “myth” of those who took advantage of the war and of the mirage of easy gain, where the law of the physically powerful seemed to be the only law feasible. Many of them have witnessed their friends die in peace, not in war. Others have lost parents and family members. Consequently, there is always a hint of sadness in their eyes. And those melancholic smiles mark the time of their childhood, never really lived to the full.

At the end of the war the Bosnians have had to deal also with other consequences: more than one hundred thousand mines infested the territory during the years of conflict and it will take another ten years to clear all the areas at risk. Adis was thirteen when an anti-personnel mine nearly killed him. He was going to play football with a friend. After various operations, the loss of his left eye and right arm, he has pulled through. Only four years previously he had lost his father and grandfather, both killed during the siege. Fifteen years later, Adis is a married man. “For the first time in my life – he says – I am happy”. Without stealing images, mine was more than anything else a co-division of memories and visions, of moments truly experienced and others only imagined. Then, one fragment at a time, I started putting together the puzzle of the Bosnian identity which had been violated by the longest siege in modern history, focusing on the lives of the young Muslims, Orthodox and Catholics, among dreams of release for the future, emulations of western models and pressure towards nationalism. This is life in Bosnia now, in the black and white of frozen emotions, a transition still present between past and future. Where dreams run next to nightmares, hate next to love and, in the inverse rules of history runs a newly found desire to serge ahead, incarnated in the new generations. Where a kiss rekindles hope, amid the obscure meanderings and backdrops of the mind.

Matteo Bastianelli (1985) is an Italian photographer, filmmaker and journalist living between Rome and Sarajevo.