The Lithuanian SSR Society of Art Photography

In the beginning of 2012, a huge amount of publications related to photography as a medium were published in Lithuania. To name a few: Lithuanian Photography: 1990-2010 by Agnė Narušytė, Nihil obstat: Lithuanian Photography during Soviet times by Margarita Matulytė and The Lithuanian SSR Society of Art Photography by Vytautas Michelkevičius. The latter will be the subject discussed in this review. It should be noted that the English version of the book has come out last month.

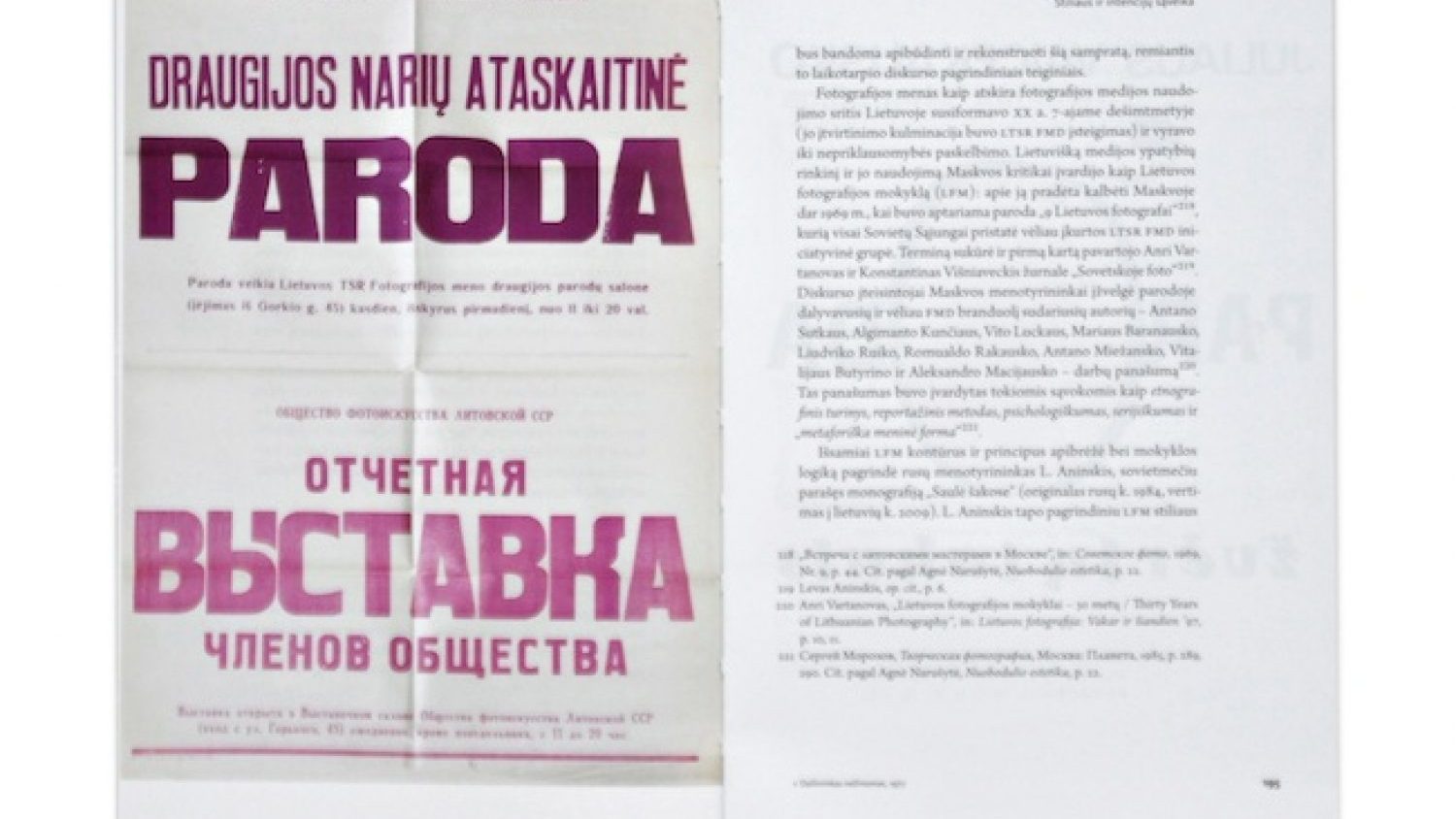

What makes it different from other books that have been released is the method used and mastered by Michelkevičius himself, but let’s talk about it later. The subject of the book is the Lithuanian Soviet Socialistic Republic’s Society of Photography Art, founded in 1969. At that time it was the only and most important organization coordinating the development of art photography in Lithuania, engaged in the production and distribution of photography. This society was the initiator and ‘dealer’ of nearly all sorts of photography-related matters. After the establishment of the Society of Lithuanian Photography, thematic, historic, personal, collective, retrospective, genre and other exhibitions were initiated and organized. Lithuanian photography exhibitions with photographs by Algimantas Kunčius, Aleksandras Macijauskas, Romualdas Rakauskas, Antanas Sutkus and others began to travel abroad.

One of the most important travelling shows was the exhibition of nine Lithuanian photographers organized in 1969 in Moscow by the Kaunas Photo Club. The exhibition was a great success. Photography theorists sought the ways to describe the specificity of Lithuanian photography (combination of a subtle artistic excellence and ideological reliability) and introduced the term ‘Lithuanian School of Photography’. It was the turning point in Lithuanian photography and that happened thanks to the SSR Society of Photography Art. Michelkevičius in his book attempts to describe how multifaceted and inclusive this organization was.

Perhaps, the very first experience when holding a new book in your hands, is about its cover and design. The book by Michelkevičius bends like a glossy magazine and covers with the fingertips of the first owner, of course, at first the one who sells the book leaves a few on it. You may ask, whether it is meaningful and necessary to talk about the cover and material of a book this much. In this case the answer is ‘yes’, because the design is very important. Because Michelkevičius is a media theorist, everything must contribute to the book, which, in fact, is a medium in itself sending out signals. The black folding book cover, where you can leave your signature in terms of fingerprints, and every page of the book that is made of a magazine-type paper, as well as the specific way illustrations have been added to the text is a result of careful planning. By the way, the book cover has one more important purpose – it is a time map and a theme atlas that you can take off the book and, for example, hang up on the wall as a poster. Therefore, acknowledgements should be given to the book artist Tomas Mrazauskas who did not step back, when the author wanted to see the book to look like a magazine, yet retain the quality of a book. We have to admit that the balance is recovered and discovered. Advice to a pedantic (literally) reader: this book-magazine is extremely sensitive (in a material way) to usage, so traces of usage and time engraves quite distinctly. On the other hand, you can leastwise see (and feel) that this book has been read many times.

A bunch of rich colourful illustrations in the book is always located on the left page and on the right page you can find the text. This kind of image and text installation has been inspired by Marshal McLuhan – the guru of media theories, who structures his books in a similar fashion. In fact, in McLuhans’ books the illustrations are located on the right page, because, according to the rules of reading psychology and mechanics, the reader usually reads the right side of the book first. McLuhan thought that the image was more important and more attractive in postmodern culture, so, in order to catch the reader’s attention, he placed the image on the right page and the text on the left. Michelkevičius is of the opinion that the text is more important than images, thus the image and text have swapped their places accordingly.

With regard to the content of the book, it should be noted that the book is based on a doctoral dissertation. However, it has been adapted to a common reader, for example, the part, which contains reflections about methodological nuances, has been shortened and streamlined. Furthermore, according to Michelkevičius, a reader interested only in photography and not theories can skip the first part and go straight to the second one. The research method is particularly important in this book. Keeping in mind photography as a medium, Michelkevičius discovers and provides a specific access to speak about photography as a media dispositif. He explains what a dispositif is and how we can talk about photography as a media dispositif.

In this case, according to Michelkevičius, when talking about a certain content (The SSR Society of Photography Art), it is important to define the concept of photography as a medium. He writes: “The medium of photography is defined as a complex of technology with an intention and a content with medium, surrounded by the social content, where the media production and spread is regulated by institution. One of the most important functions of photography – the knowledge transfer, which takes place, when the photographer interacts with a technology (photo camera programme) and the social content”. Yet, Michelkevičius emphasizes that, in order to apply this concept in the studies of photography, there is a lack of a holistic concept, which links all these elements. When discussing Lithuanian photography in 1960s-1980s, the dispositif becomes the holistic concept.

The concept of the dispositif, which first appeared in post-structural theories, is quite complicated. However, in this book (maybe because of the time period), after an accurate analysis and reasoning, it becomes very convenient. Knut Hickethier – a German media theorist, defined the dispositif as something that could help to talk about photography as a whole, taking different edges of photography as a medium all-in-one. In fact, the concept of the dispositif does not contradict to talking about the network and reticulation. In this case the concept of rhizome coined by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in the book A Thousand Plateaus (1980) must be mentioned. The image of rhizome, borrowed from botany, is a non-hierarchical and horizontal derivative, which can define, for example, the reticulation of the SSR Association of Photography Art. Here the dispositif becomes a method that defines a network whose measurements cannot be connected to one united structure.

As regards the fact that this book is also designed for the photographers, who are interested only in photography and not in theories, there is an option to jump straight to the second part, which contains chapters about the activity of the SSR Association of Photography Art. However, the principle of constructional methodology cannot be avoided, although it can be read without articulation and, in my point of view, this kind of reading experience is a natural example of the dispositif. Because the individual does not do everything at his own will, there is an arbiter (the dispositif). Michelkevičius says “[..] an individual did nothing at his own will, but there was an arbiter (in this case the dispositif) who ‘knew and predicted’ the way that everything had to be and just revolved the engine of photography. [..] from more global perspective without any certain persons, step by step, the associative network between two active characters – people and objects – appears. [..] while investigating the activities of the Association, I tried to find the basic principles of its work and there was no aim to describe any individual contributions”.

This book sets an all-embracing reticulate trap. And it is not important in what way it is read. Whether by studying and keeping in mind the methodological structure or just experiencing and reading the text complements (maps, illustrations) the book still exists. That is why I dare to call this book the dispositif.