Murray Ballard

British photographer Murray Ballard (1983) has been working on the project The Prospect of Immortality for six years (2006-2012). The project has been named after Robert Ettinger’s book published on 1962, which laid the foundations for the idea on cryonics – freezing human or animal bodies after their death with the hope that someday highly advanced future technologies will enable resuscitation. Work on the project started in Great Britain, where Ballard was born, but later the research on the international community of cryonicists, which, as it turns out, exists in reality, not only in science fiction, led Ballard to the USA and Russia, too. Currently there are around 200 patients preserved at low temperatures around the world, with several thousand subscribed to this procedure after death.

How did you become interested in cryonics?

I was doing a project at University about photography and its relationship with time, preservation and death. I drew up a list of subjects to explore: taxidermy, embalming, Egyptian mummies, seed banks etc. As an afterthought I jotted down – cryogenic preservation – not really knowing what it was. During the project I happened to come across an article in The Guardian newspaper with the headline Freezer Failure Ends Couples Hopes of Life after Death. It told the story of a French couple who had been frozen underneath their Chateau in the Loire Valley with the hope of being brought back to life in the future. Unfortunately the experiment came to an end when the freezer broke-down. The article outlined the concept of cryonics and got me researching the subject online. Needless to say my curiosity got the better of me and it developed from there.

Did you find it difficult to access people and places you have pictured in The Prospect of Immortality?

Some were certainly trickier than others. I’ve been working on the project for a long time so I’ve built relationships with people. I started off locally, photographing the cryonics community in the UK, and then, with the UK cryonicists vouching for me, I approached the facilities in the USA and Russia. Like most subjects, which require access, it’s a process of meeting people and explaining what you want to do before they have the confidence to let you in.

Cryonics obviously is a subject people have a lot of prejudice and stereotypes about. Did you find it destructive when working on this project? I mean, in a way that you would feel pressurised to depict something more than those stereotypes?

I don’t feel under pressure to depict cryonics in a certain way. I started the project with no real knowledge of the subject, I thought it was an idea that existed only in science fiction. Like many people, I also thought Walt Disney had been frozen, but it turns out that’s an urban myth.

Throughout the project my assumptions were challenged and I want my project to be representative of that. At the end of the day my project is quite simple, I’m trying to communicate my experience through photographs.

Have you started to work on any new projects?

I’m currently finishing up a commission about the UK’s renewable energy industry. It’s for an organisation called FotoDocument and the basic premise is to look at how the UK government is going to meet the European Renewable Energy Targets set out in 2009, which requires the UK to source 15% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020. I’ve been photographing: offshore wind farms, solar arrays, hydro-power stations, tidal turbines and wave energy converters. It’s been really interesting to see how this new industry is rapidly expanding.

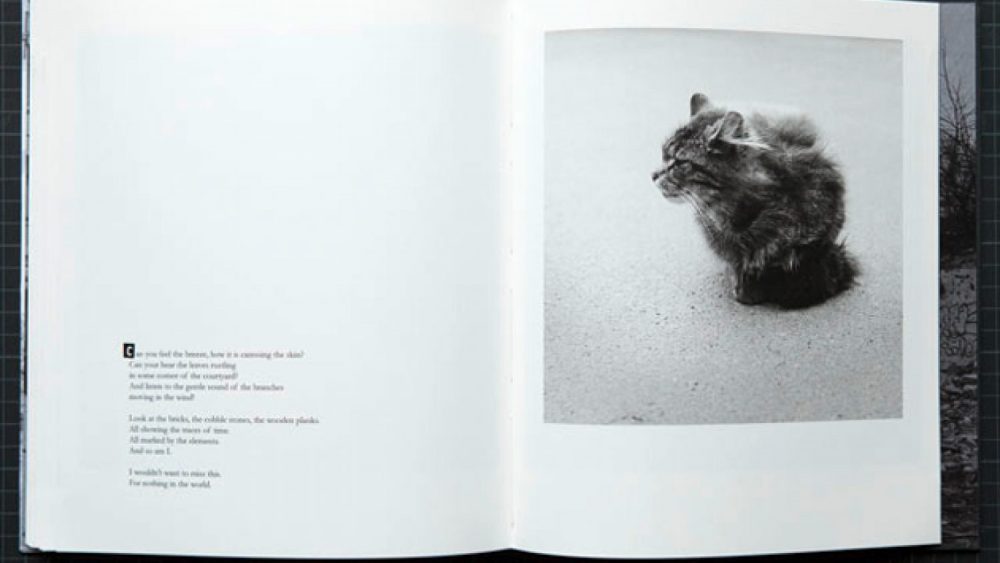

I’ve also made tentative steps with a new personal project. In a way it follows up on The Prospect of Immortality, but it’s very different, much closer to home and more about the everyday cycle of life. I’m desperate to get going with it, but it’s hard to find the time whilst working on The Prospect of Immortality book. I’m currently working on it with Stuart Smith, on the design, and with Anne McNeill as editor. I’m hoping to bring the book out this autumn, but time is ticking-by and it might slip to next spring. As Stuart keeps telling me, the project’s taken me five years to shoot so it’s not worth rushing the book out for the sake of a self-imposed deadline.

You work as an assistant for Magnum photographer Mark Power. Does it influence your personal work and do you find it easy to combine working on personal projects and being an assistant?

I’m very lucky to work as Mark’s assistant. I normally do two or three days a week. Most of the work I do for him is in post-production, film scanning and printing. It’s fairly flexible, which means I can usually fit in my own work without any problems.

There is no doubt Mark’s influenced my approach to photography. I used to be afraid of acknowledging his influence, but I’m not so worried about that now. Everybody has influences, it’s about how you use them and make them your own that counts.