Interview with Jan Grarup

During his 20 year career, Danish photojournalist Jan Grarup (1968) has reported from many of the world’s conflict zones, including the Gulf War, the siege of Sarajevo, the Rwandan genocide and Afghanistan. He resides in Copenhagen, but travels a lot, spending at least 100 days away from home each year. Increasingly, the photographer has turned to long-term personal projects – planned to be published next year, his book on Somalia will be the result of more than four years of work. Grarup’s photographs characteristically address human rights issues. He won his eighth World Press Photo award this year – first place in the Sports feature category – with a story on a female basketball team in Somalia, exposed to threats from local radical Islamist groups. The photographer started a fundraising campaign for the women’s cause, also adding his own prize money to the fund. This May, Grarup visited Riga as part of the World Press Photo 2013 education program, giving a public talk, as well as participating in a portfolio review and leading a 3-day masterclass for local and foreign photographers. Meeting him for the first time, it seems Grarup could also carry off a second career as a rock star. While here, the photographer was open in sharing his honest opinion, advice and stories about life and work in conflict areas.

What do you think are the characteristics of a successful photojournalist?

I think there are several – one of them is dedication. This job will not make you rich. It comes with a lot of consequences to do what I’m doing, and it’s difficult to have a normal life at the same time. Secondly, you need to have an honest and personal interest in the stories that you do in order to make them interesting to other people. For me, that’s the clear difference my work and what photographers who just follow assignments do. If they don’t have their heart in it to begin with and just do it to make money, they could just as well build a car or a chair. Whether a photographer is doing reportage, sport, or nature photography, you can always see the 10% extra if they have a personal interest in it. I always have a lot of stories that I want to do. I have a big blackboard at home, and whenever I see something in the newspaper I print it out and put it on the wall – usually I don’t know why yet, I just know that I want to look into it at some point. You have to keep an open mind. If you just walk around, read the newspaper, listen to the news, talk to people – ideas pop up. A common danger for photographers is going somewhere with a specific idea of a photograph they want to take already in their mind. If you walk around looking for that image, you might miss out on 10 other very important photographs on the way. You always have to be present where you are.

You have travelled and worked extensively in Africa, most recently Somalia. How did the project there start and why have you continued going back for four years already?

The Horn of Africa is very interesting in general, because it has the aspects of war, warlords and religion, the fight between fundamentalist Muslims and normal Muslims, Sharia law, as well as famine. Somalia has seen two decades of war, and it is strategically very important due to the Gulf of Aden. The people there are amazing. They deserve a much better life than being caught up between religion, famine and warlords, and that’s why I’m trying to document it. The story is very complex. It’s not something that you can do and understand in two weeks. On the contrary, the more you go, the more complicated it becomes. It’s like personal relationships – when you meet someone for the first time, you only see the surface, and slowly you scratch off the layers. Beneath the facade is something different and more complex – it takes time to get closer, and that’s why I keep going back. It’s not the longest project I’ve done in Africa – my Darfur project took 7 years. I like doing long-term projects, because it clarifies a lot of things for me and I think it makes my stories stronger.

In your lecture, you spoke about working with a lot of bodyguards in Somalia. How easy is it to work as a photojournalist there?

In Somalia, I work with a lot of security. It’s necessary, otherwise you would be killed straight away. In Syria, for example, you have a frontline with the Assad forces on one side and the Free Syrian Army on the other. When you go to the frontline, you can get shot or bombed – but at least you know where it is. In Somalia it’s very different. You don’t know who is a radical fundamentalist planning to kill you. The threat is constant and immanent – it’s invisible, but you know it’s there. Not just fundamentalists – there is also kidnapping, hijacking, piracy.

How do you deal with these feelings of threat and fear in the everyday, while you are working?

I don’t really care. Mostly I’m just annoyed that the security is there. It takes a hell of a long time to collect all the guards from the safe house in the morning. I don’t work with security everywhere. In many places I just work on my own, and I by far prefer that. I have a lot of experience by now, and I know when I feel threatened. It can potentially be very dangerous to feel the way I do – to think you have everything under your control. On the one hand, fear can be a motivating factor in terms of understanding something, but it can also stop you from doing what is necessary. If you are too frightened when you go into a war zone, you should really think about what you’re doing. Not much good photojournalism is produced by fear, since you are thinking more about your own security than the story. I don’t know why I feel like this. It’s not that I want to sound heroic or brave, but the fear has disappeared over the years.

What are your hopes and aims regarding a long-term project like the Somalia one?

Obviously, I am documenting a period of time in Somalia, which is important. Ten years from now, Somalia will look different – either for the better or for the worse, depending on who wins. I don’t walk around with the idea that I can change the world – none of us can. However, I can come to Riga and show my work and tell the story, and hopefully make someone think and reflect upon the situation in Somalia. Good photojournalism shouldn’t answer questions, it should raise questions. After showing the images yesterday, there were questions from the audience on the future of Somalia and the possibility of democracy there. Hopefully, people went home with ideas and questions, like – “What is the solution for a country like that? Why aren’t we doing more?” Latvia and the other Baltic countries are also interesting in the sense that democracy is still something you need to learn, after having a system imposed on you for many years. Democracy is actually a very fragile thing. This shows very clearly now in the Southern European countries – Greece, Spain, Italy. There is a lot of corruption and poverty. Greece could face a military coup at anytime, due to the instability of the country and the economical situation. Never take democracy for granted – it can disappear really fast.

Tell me about the series you won the World Press Photo award with this year – how did you meet the girls, and weren’t they afraid to be photographed?

They were very scared to begin with. I met them through the work I was doing in the country. The story came up while I was talking to someone, and it seemed unbelievable at first – woman playing basketball in Somalia. So we went to look for the girls and spoke with one of them, who explained the story. At first they did not want to be photographed, as they get threatened a lot and felt it would be dangerous. After talking about it among themselves, they agreed. I went back a couple of times to photograph them training, and take a few pictures at their homes. They explained why they were playing and their dreams and hopes for the future. Again, a lot of the good stories come to you if you are somewhere for a long time, and talk to a lot of people. You can’t research everything from back home.

Have they seen the photographs themselves?

They have seen the pictures and they like them, but they don’t know about the money collected for them, so it will be a big surprise when we get there. I really like the fact that this is a positive story coming out of Somalia for once. Showing this side became an aim when I met them, and it will be an important part of the Somalia book. The girls themselves don’t realise they are fighting for so much more than just basketball – gender equality, female rights, democracy, the freedom to choose. Of course, that’s why they are threatened. It’s not very Sharia for women to play sports. They didn’t do this to show they could do what they want – they did it simply because they wanted to play basketball. It becomes a natural form of protest.

This year, the World Press Photo exhibition visited Riga for the first time in 20 years. Do you think it is important for people to see these images?

Absolutely. I think World Press Photo has the unique possibility of showing people the state of the world. It focuses on the big media events of the last year, and of course, this is Syria and the Arab Spring, the drug war in Mexico. But it’s also about daily life stories and women playing basketball in Somalia. It’s important to actually look at someone else’s life, outside your little box called Latvia.

What do you think about the scandals that traditionally follow every World Press Photo contest? This year, for example, regarding the work of Paul Hansen and Paolo Pellegrin. Is it important to raise these issues and encourage debate?

I always think that debate within photojournalism is interesting. What I don’t like about this year’s discussion is that it might be politically motivated. It seems that the Jewish lobby are trying to disqualify the winning picture. I think that everybody now agrees that this picture is not fake, and these kids were actually killed in an Israeli air strike. Why is this questioned to begin with? Is it due to genuine suspicion of a forgery? I’m quite sure it’s politically motivated – to remove interest in the actual content of the picture. Of course, whenever a theme is controversial, there will be a side that doesn’t like the image.

It’s quite a different story with Paolo’s picture. When a subject of the picture claims that he is not represented truthfully, it becomes dangerous. Photojournalism has to be as true as it can possibly get. Of course, the objective photograph does not exist. Everything depends on the eyes and mind that see. But the people you photograph should always be able to recognize themselves, good or bad. If you start to question that – if people start becoming only actors in our pictures – the discussion enters an important and dangerous territory.

I have never claimed that my work is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. I have always said that this is a fragment of the truth as I see it. If I go to Somalia and take 10,000 pictures and publish 150 of them, I have already selected what you should see. If I take a picture of a child in front of me crying from starvation, you don’t see the ten kids behind me smiling and laughing at a white man taking pictures. It’s my choice to photograph what I see as important – I could also turn around and take a different picture and say that everything is good in Somalia, the kids are happy. However, the photographer should never become part of the story. The kids in the photograph should not be crying or laughing because of me. You have to be really careful about your role as a photographer.

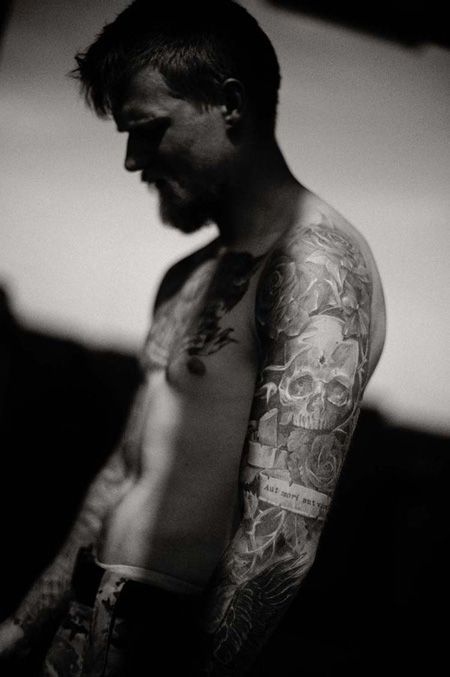

Tell me about your ongoing story about the Danish troops in Afghanistan. Why are their tattoos significant?

Denmark has had a presence in Afghanistan for 10 years and lost 42 soldiers there. In many ways we are fighting a war difficult to win. The effect on the Afghan people has been covered extensively around the world, including by me. I’m also interested in the young men who go to fight a war and come home with scars on their body, mind and soul. The tattoos and stories behind them are fascinating because they reflect what they have been going through. Many of them are violent, but they are also about brotherhood and honour, about losing friends or days when they almost lost their own lives. There is also a religious aspect, with a lot of Vikings and Nordic mythology, and tattoos of crusaders going to the Holy Lands. Them against us. Of course, this is extremely provocative toward the Muslims living in the country, and raises the question of why are we there – is it to convert them or to solve a problem with terrorism? It’s a personal investigation, and I think it will also interest a lot of people in Denmark.

You also have a lot of tattoos – is your interest connected to this?

I do tattoos for other reasons but all of them have a meaning to me – it could be a mood I’m in or a situation that I want to remember 10 years from now. I can look at my body and know why I had each one made.

How have your 20 years of experience of working in conflict zones around the world changed you as a person and your outlook on life?

It has changed me dramatically, because my interests are spread out all over the world. I feel enriched by knowing and having met people in so many places – not everybody has this possibility. It has definitely changed my way of looking at other people, both for the good and for the bad. There’s no straight answer, because I’ve seen more evil in the world than just about anyone, but I’ve also met so much love and empathy and caring for each other. Even though the world is a large place, many of the issues we are dealing with – whether in Riga, Denmark or Angola – are in many ways the same, only on different levels. People should remember that we are not that different.