10 minutes with Erik Kessels

Dutch artist Erik Kessels is an art director, curator, publisher, and collector with a passion for found photography. When he runs across a bizarre photo album in the flea market, he takes it with him to republish in a book or to store in his own archive. He admits: “For me publishing is the hobby that got out of hand.” His office in Amsterdam, located inside of an old church, is the home for the KesselsKramer ad-agency and KesselsKramer Publishing house, best known for its long running series of Useful Photography magazine and the book series In Almost Every Picture. Now in its fourteenth edition, Erik Kessels’s series returns to a favourite theme: imperfect images, damaged by accident or design. Kessels is the artist, who pushes the boundaries in the field of photography, exploring the medium of photography in many ways. One of his best-known works is the installation Photography in Abundance for which he filled-up the room with 1 million printed images to illustrate the number of daily uploads to Flickr.

I asked Erik Kessels some questions regarding his fascination with found photography, the publishing and his upcoming project.

What does fascinate you in “found photography”?

I am interested in the authenticity of things. I often visit flea markets and at some point, I started to find a lot of photo albums. I became interested in how amateurs have produced very important photo series. I am interested in the imperfections you see in these images, which make them authentic. Family albums in flea markets are slowly disappearing. 10 years ago you could find quite a lot of them in markets but it is quite rare to find that nowadays. When you find those images, you could just leave them there, but I find it interesting to take them out of their original content and then put them into a new context and tell the story about it by creating a mystery around it.

The book In Almost Every Picture, for example, is a way to express these series of photos, to make a pictorial novel out of it. With the hope that people start to look at these images again. I point them out and make the sequence, a new story. I think it is important to dislocate the images.

Can you tell about your latest photograph or photo album you have found?

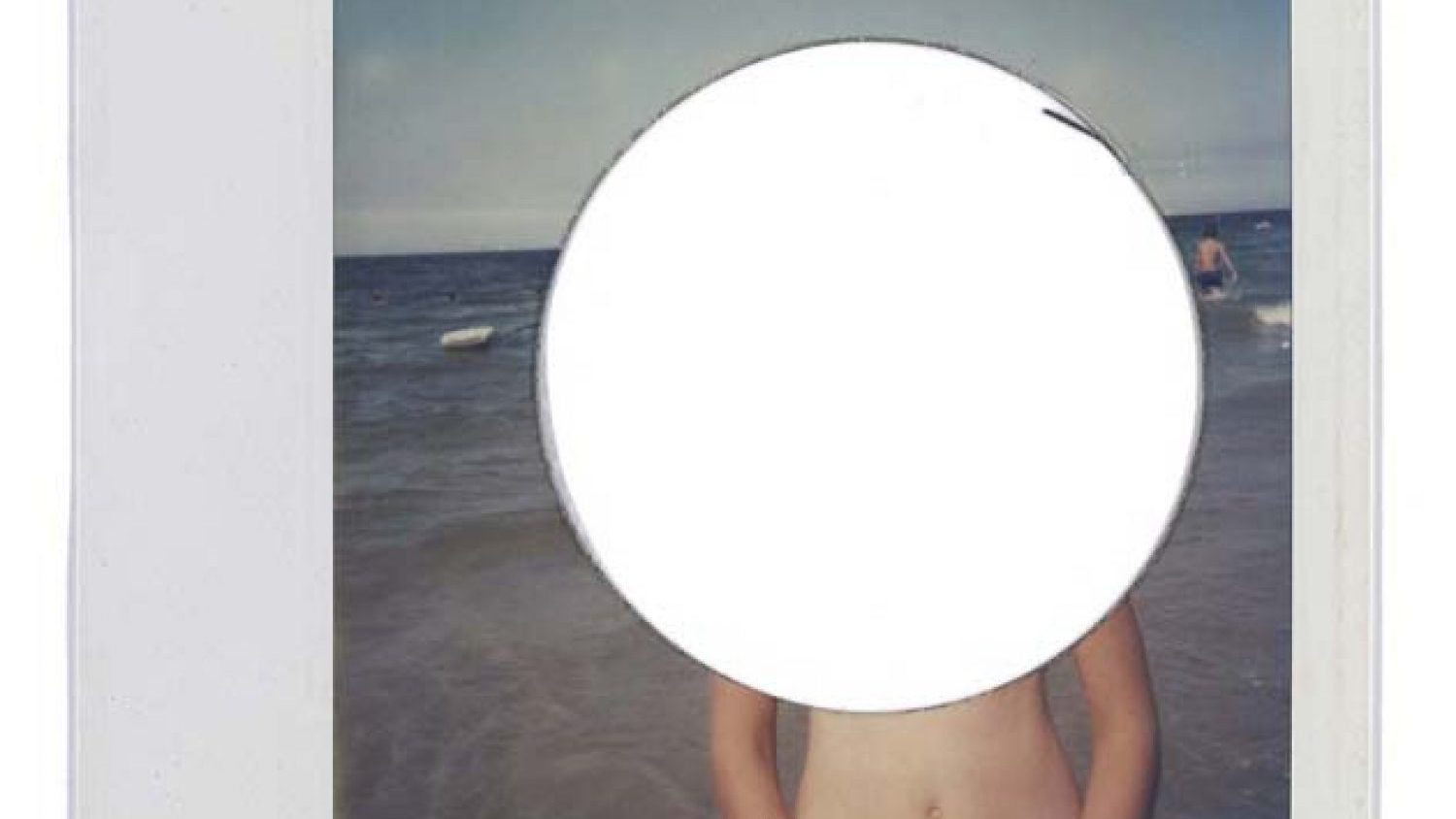

The latest, and very interesting one, is the one I made a book about. I found about 100 of Polaroids, all taken at a beach. It is quite bizarre that all the Polaroids have a white hole in the middle. This is also something what interests me. More than just a single image, it’s a sequence or series of images with a certain idea, story or even a hidden story behind it. In this case it was quite intriguing as all of them were taken at a beach. In the end I found out that these all were taken in the eighties. Taken by a photographer at the beach who clipped holes in the Polaroids to make a button out of it. He sold the buttons to the people in the beach. So the rest of the Polaroids were just a waste. That makes it quite intriguing. In the book I put them in a way together that the hole is always at the same spot. This is a way how you edit it and put it together, these are all choices you make to re-appropriate these images.

In this case you worked more as a book designer than a story creator?

In this case, yes. For other projects it’s more about what kind of a narrative you create, what kind of editing you do.

For instance, there is a book I did with photographs from the people who photographed their black dog. At the end of the book, you can see that they become frustrated so that they start to overexpose the images, you see that the background is totally bleached out and finally you see a little bit of the dog. That’s an image that was maybe taken by coincidence, but I bring it as the story, which tells that they get so frustrated that they start to overexpose the image. So I don’t manipulate the images literally, I don’t photoshop them, but with the help of editing I may manipulate the story.

As the creation of the book is just the first step, what are your further steps to deliver your work to the audiences?

We have a distributor and most of the books are distributed with a certain circulation. That is something you have to build up. The edition for my books and the magazine Useful Photography is 500 copies. To make the book is one thing, but the hard work starts when you have finished the book and after it is printed you have to start to promote it and ensure the publicity. You need to make sure that people hear about it. For self-published artists that might be the painful part, which starts after making the book. There are a lot of channels now like art book fairs, photography fairs, small book markets, you can get involved. At the art fairs there are often curators, collectors, a lot of interesting people which can have a more extensive knowledge of what you do and what kind of book you have made. On the other hand, that is not the main market product and there might be just a small niche of people who are actually interested in this kind of work.

How do you see the future of book publishing in the field of photography?

It is an interesting moment in time, a lot of people are complaining that the amount of books is just decreasing and that there is no future in printed works. But on the other hand, you see a lot of young people publishing and also self-publishing, creating almost a trend for it.

Maybe that has something to do with the fact that people really like to touch books, feel the paper, enjoy the design of it. For a lot of photographers and artists it is also a way to express themselves. The textile feeling of the book is also very important. For instance, now you can see that there is a lot of vinyl in shops again. Who could have ever thought that this would be en vogue again?

Books and vinyls and similar things, they feel more authentic and real. At the moment, and maybe also in the future, the wish for the “real” will increase.

What’s your next project?

I am now going to do a project in Italy and I’m going to the festival in Emilia this May. I am doing a new project there about my father. The project is called Unfinished Father.

Last year, my father suffered a stroke and has since been barely able to speak or move. Prior to this, he was extremely active. His projects included restoring examples of that Italian icon: the Fiat 500 (or Topolino.) Before his stroke, he’d completed four such restorations and was working on a fifth, the half-finished carapace of which remains at his home.

My plan is to transport this last Topolino to Reggio Emilia and show it alongside the images my father made to document his restoration. For me, this work is about a man who — like his vehicle — will never be complete, but remain unfinished. While films and stories teach us that endings are neat (and often happy), the truth is that everything ends abruptly, more or less half-done. No matter how carefully we plan and how precisely we execute those plans, there is no guarantee that they will reach our hoped for conclusion.

Also I’m creating a supplement to it, a small book which also will be unfinished and where the viewer has the chance to finish it by himself. In this special case, the project was first and then the book came later.

What would be your advice for artists to get their work noticed?

My advice would be – recycle your own work! Often, even though your work has been seen, there are still many people who haven’t seen it yet. You should not be afraid to show your work for a long time. Recycle your own work, keep showing it and continue to communicate with your work.