Interview with Elina Heikka

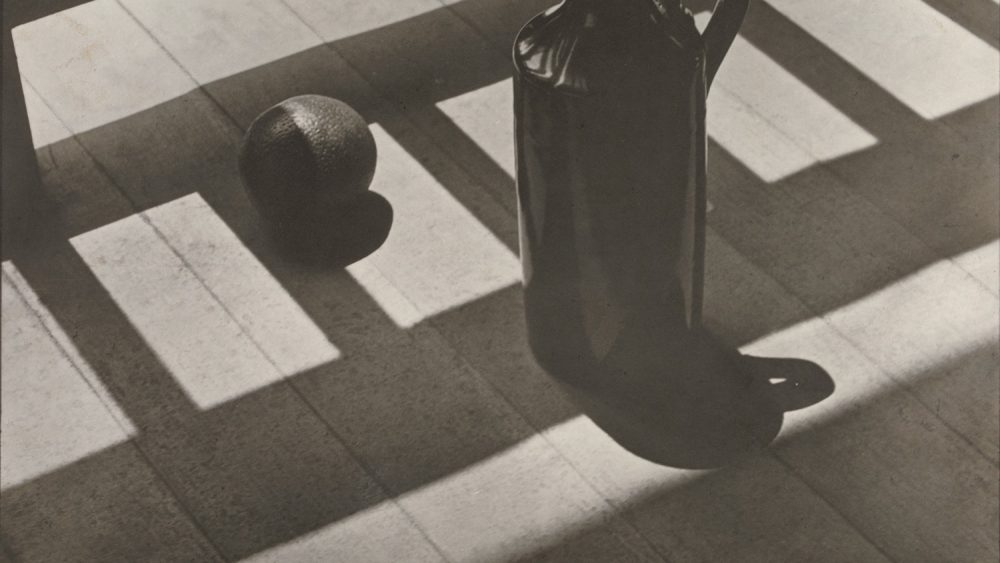

Elina Heikka has been the director of the Finnish Museum of Photography for eight years. The Museum was founded in 1969 and for nearly 25 years it has been home for the cultural centre Cable Factory. It is a renovated complex of an industrial building hosting two more museums and several galleries. The Museum’s collections include about 3.7 million pictures spanning the various user cultures in photography. Currently visitors of the Museum can see the show Darkroom that looks both at the history of photography and the current revival of darkrooms and traditional techniques. Works by more than 60 photographers, spanning from the 19th century to 2015, demonstrate the versatility of the techniques and the changing ideals of photographic printing.

How did you come to work at the museum?

I studied art history and I was specializing in photography. I was writing my Master’s thesis in photography at the time. I have also a background in amateur photography, since as I was a member of the camera club at the university. And then I worked in a photography magazine as an editor in chief, Valokuvaus, which stands for “photography” in Finnish. After that I started here at the Museum as a researcher, but around 2000 I moved to the National Gallery and worked there for seven years. I returned back when I was elected to be the Director of the Photography Museum.

When you look back how the Museum has changed and developed since you came?

I think not only the Museum has changed but also photography. I have to emphasize that our Museum is not only about photographic art but also photographic culture, which means that we are also interested in everything what’s happening in photography. And there are so many things going on in photography since the connection between photography and internet was established. The photographic world from 2007 and 2015 has changed completely. In 2007 photography was not that essential part of social media as it is today and I think that it opens great opportunities for our Museum, because the general interest in photography is more than ever before. As a Museum we try to understand what’s going on in photography and also use social media to deliver our message and follow our mission.

The other thing is that the Museum is more international now than before if you look at our exhibition programme. We have a few more people working at the Museum. For example, a while ago we didn’t have anybody working for communications and marketing, but now we do. Also, we have been publishing quite a lot during my time here. We don’t publish monographs of the photographers but at least once a year we make one research-based exhibition and on that occasion we always try to publish a book. Our latest publication is about survey of the Finnish photographic art of the 20th century.

As a museum how do you deal with that significant amount of images around us that increases every day?

In terms of digitalization it started in the 1990s, when all museum collections started to digitalize their collections. But we are still questioning how to collect digital photographs. We don’t have any precise answers yet, but, for example, we have a research project called Collecting the Digital with partners from the National Museum in Sweden and Arhus City Archive from Denmark. Within the project we try to find out what’s happening globally and how the museums are reacting, do we have strategies and if there are any models for us to follow how to work on with the policy of our own. I have to say that in terms of digital-born data we are just in the beginning. All people use cameras and we want to be active partner in the discussion with our society on what to do with these images. Every second week someone from newspapers ask our opinion on these matters. We also had very important exhibition #Snapshot, which was about everyday photography and we were discussing what’s happening at the moment, when we live in this shoot and share culture.

Can you tell me a bit more about your collection – how does that process happen, how do you engage with photographers and institutions, do you buy works or get them donated?

There are different ways in terms of collecting. If somebody wants to donate photographs we have a group at the museum that discusses these donation options once a month. We try to understand if that is something we need for our collection, is it there a new narrative, is it an artist of high quality. On the other hand we are purchasing contemporary photographic art, not much, maybe 10 pieces annually. And then sometimes we approach photographers if we feel that we don’t have enough work at the collection. The biggest problem is contemporary art – it’s so expensive and big, but we have very limited possibilities. Luckily since the 1990s there have been very many art museums in Finland that started to buy photography. But if you go back to the 1970s and the 1980s, our Museum is the only one where you can find works from these periods. And I feel that this work somehow is a very essential and valuable part of our collection that you would not find in other museums in Finland.

In our collection we have prints and also large negative archives. Many photographic museums in Europe don’t deal with the negatives because you have so much more problems – there is always thousands of them, it’s hard to catalogue them exposure by exposure, and nobody has time to look at them all and find something interesting. In terms of the photographic art market, it’s not the negatives, but the prints that you must have from a photographer. For instance, the Moderna Museet in Sweden only works with prints, so does Brandts in Denmark. From the archival point of view, it’s also much easier that way.

Since you are buying contemporary photography, would you be able to comment on the photography market in Finland and what role the Museum of Photography plays there?

We are very small, we don’t have that much money, but I have to say the photographic market in Finland in general is very limited. Museums are buying photographic art, but I wouldn’t know the total annual value. By all means, it’s not very big. Those Finnish photographers, who make their living from photography, are selling abroad. You can’t be a photographic artist in Finland who earns money from selling work in Finland. The biggest market of photographic art is the USA, but it seems that a very few Finnish photographers have been able to go to that market. The customers are mainly in Europe, which is a bit problematic, because there has been a recession since 2008.

What’s going on in the Finnish photography at the moment?

You must know the Helsinki School of Photography. We don’t have an actual school with that name, it’s called the Aalto University, but the Helsinki School of Photography is a marketing brand for Finnish photography that has been very successful since 2004.

It is special that already since the late 1960s and early 1970s, we have had a very strong photography scene. The Museum was founded in 1969, photography-related education at the university started in the early 1970s, photographers started to get grants in late 1960s, the first photography gallery and a magazine was founded in the 1970s. We had the entire infrastructure but we lacked marketing. Then it was around the 2000s when the Helsinki School concept was created. It was a good timing – we had a history, traditions, many good photographers, very promising young photographers and the photographic market in Europe was boiling in the late 1990s.

At the moment the Helsinki School has been here and there, art fairs and exhibitions and the number of photographers whose work has been represented somewhere in books and fairs is growing.

Why is there a certain style that applies to almost all work done by the Helsinki School photographers? For instance, most of the work is very romantic, nature related.

Maybe it’s even easier to say what they don’t have. They don’t have very documentary photography and there is no politics.

Maybe there is but it is underrepresented?

It has to do with the main figures in the Finnish photography in the 1980s, who were teachers at the Helsinki School, like Pentti Sammallahti, with his classical black and white romantic attitude, Ulla Jokisalo, with a kind of feminist phantasy, and Timo Kelaranta, who brought abstraction in the Finnish photography. A Finnish-born American photographer Arno Rafael Minkkinen has also been influential. In the 1980s photographers got rid of the social documentary of the 1970s, so there was an outburst of this romantic feeling.

But the generation of the 1980s didn’t sell anything in Finland. In the 1990s very many photographers were working with installations but it was very typical for the 1990s, and not just for photography, but in general. Of course, you can’t really put installations on the wall. With the marketing campaign organised by the Helsinki School, photography somehow returned to the wall. And if you think of the art market, it’s easier to sell something, which is not documentary or political.

Could you also tell us about your exhibition policy?

Actually our chief curator Anna-Kaisa Rastenberge is very much responsible for our exhibitions policy, I just sign the papers. What we have done until now is a series of retrospective exhibitions by mid-career Finnish photographers, especially of the generation born in the 1950s. It’s done and recently we have had more thematic exhibitions focused on some phenomena of photographic culture, for instance, we have had exhibitions on Polaroids, Surrealist postcards of the early 20th century, snapshots, and now we have an exhibition on darkroom. Also, we have had an exhibition on photo books, on photography from our civil war. Now we would like to start the series of what we call “modern classics”. We are starting with an exhibition by Alec Soth next autumn that we have co-produced with London. We are also having a project that will result in an exhibition on political photography. In January we are having an exhibition on the subject of “homeland” and you can guess that it will deal with the asylum seekers. And once a year we also have an open-call for our project space, which we have been running for 5-6 years and which attracts emerging, but not exclusively, artists.

What’s your vision for future?

To reach better visibility and get bigger audience, we should invest much more in communications and marketing, as well as fundraising. If you go to web sites of big photographic institutions, such as Fotografiska, The Photographer’s Gallery, Foam or Jau De Paum, you see that they have about 10 people working on these things, but we have only one.

And we would like to be in the city centre. We are doing very good work and we are an advanced museum, but we need to increase the number of visitors and become more popular among Helsinki citizens and tourists.