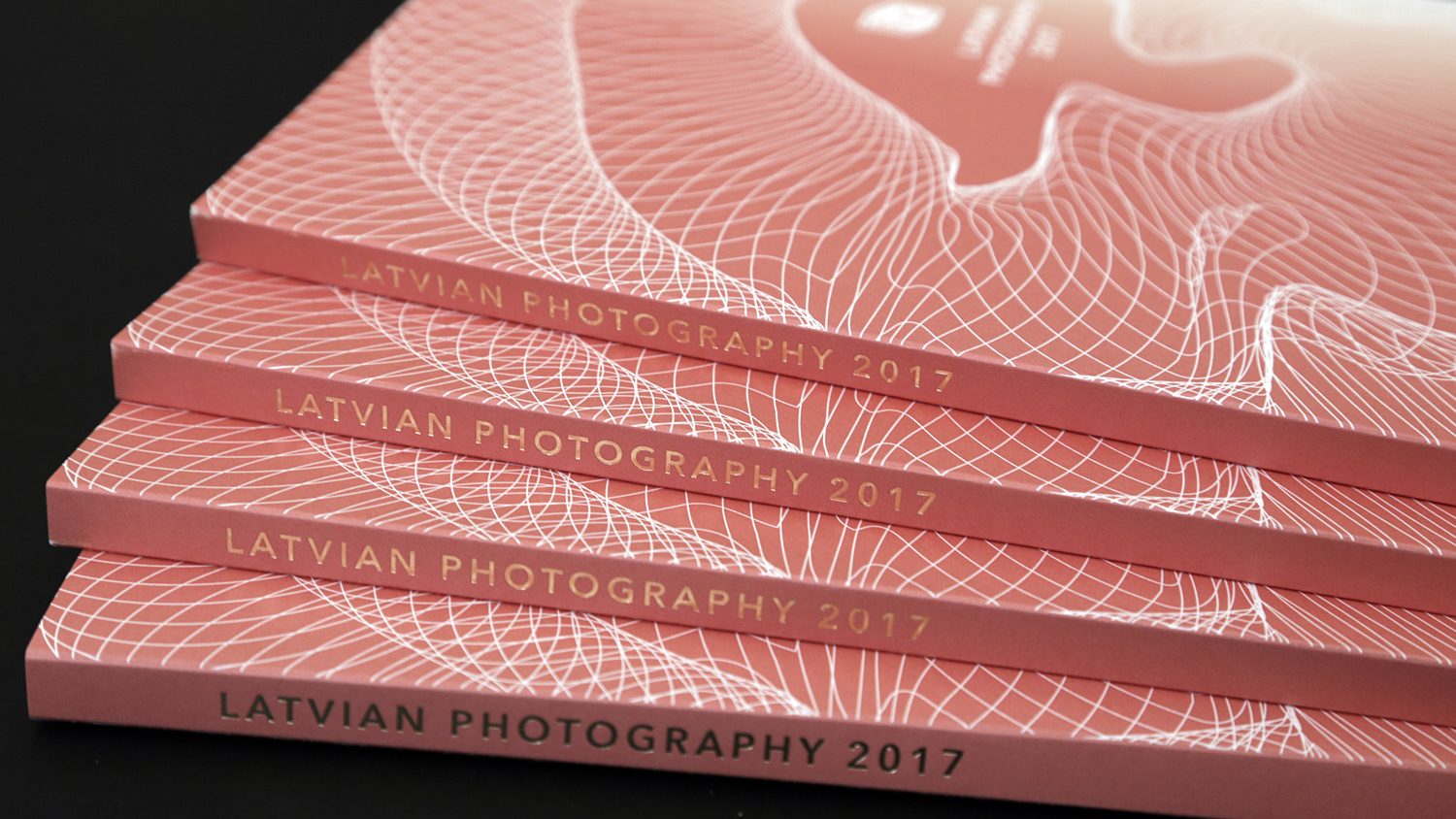

Seeking a Community. Discussion with the authors of Latvian Photography 2017

This year’s publication Latvian Photography 2017 offers photo series by five young photographers – Evita Goze, Reinis Hofmanis, Luīze Nežberte, Kārlis Bergs and Ieva Raudsepa, which focus on different communities and subcultures – from today’s adolescents all the way to costume party participants. The publication will be launched today, 8 May 6pm, at NicePlace Telpa in Riga and is the first event of this year’s Riga Photomonth festival. The editor-in-chief of FK Magazine Arnis Balčus sat down with all the authors of the yearbook.

Arnis Balčus: Although the series are dissimilar, the unifying aspect in your projects is the collective identity and community connection, which you represent in your photos. What is your relationship to these people, phenomena, community or identity? To what extent are you involved yourselves?

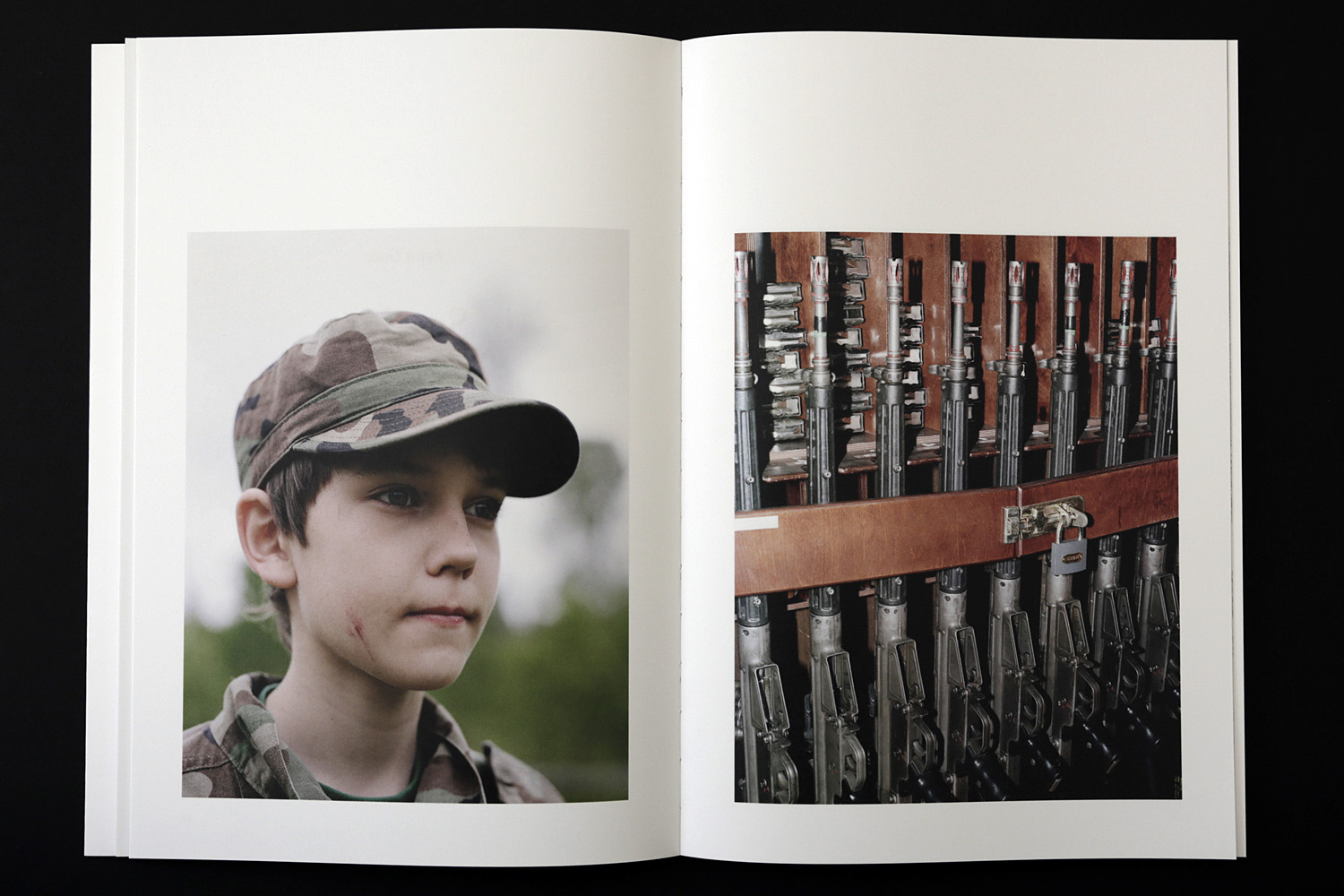

Evita Goze: The involvement has been almost anthropological. I have been taking pictures of the Youth Guard for a year and a half already. I participated in trainings, went trekking, played paintball, I slept in a tent in winter at -15° C, and learned to shoot. Yet I am not trying to document the Youth Guard as an organization; I see it as military training for kids and youth. I am trying to highlight aspects that I am most interested in, – the understanding of masculinity, training methods, the age between childhood and adulthood, vulnerability, the presence of weapons, how they try to imitate soldiers. The first time I went trekking with Youth Guards was in Pļaviņas, where my parents live. I discovered that I truly like this process. It gave me an opportunity to try something I would otherwise never try. Of course, I am an observer from the sidelines, and not part of the group. I think they perceive me as such, as well – as a person, whom the instructor has permitted to take photos. I like that photography is a medium, which allows you to become, if even just for a while, a part of some other group.

Reinis Hofmanis: My theme in Heroes is a continuation of the LARP series, which I began six years ago. The essence of cosplay lies in the fact that each participant creates his own costume and stages a theatre performance according to his character. Depending on how accurate he is, the participant then receives recognition or an award. The inspiration for the characters came from pop-culture – anime, comics, animation films, video games as well as films. In such events one can see references to all areas imaginable and combinations of the most incompatible characters.

I am not so interested in the perfection and flawless execution of the outfit, but more so in the human aspect, which shows the amount of hard work invested, perhaps, something has not been fully worked out or hasn’t been finished. The human body is also an curious factor, which can sometimes become an obstacle, for example, you either can be Batman or you cannot.

I set my heroes in an event, against a neutral wall, thus removing any excess and setting the focus on details. Oftentimes, I deliberately leave some characteristic feature of the environment in the background, thus adding a current- time reference point to the fantasy world character.

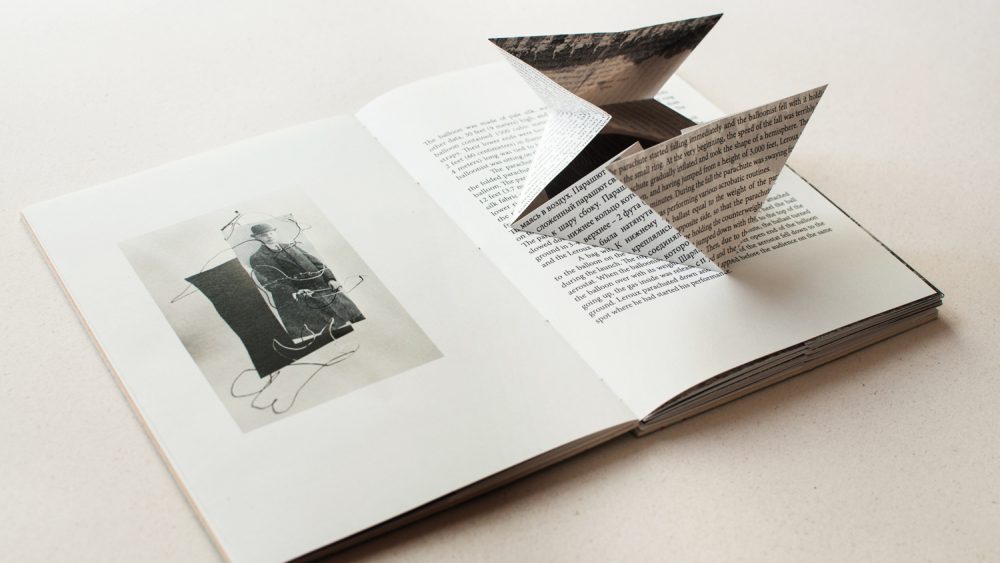

Ieva Raudsepa: By working on the project Do Your Best, which deals with national identity and patriotism, I am trying to understand what the love for my homeland means to me. Historically nationalism has been very romanticised, although, in actual fact, it is quite an irrational phenomenon, particularly now, if we think about Latvia in the current geopolitical situation – what is it that makes us protect this tiny and not very affluent territory somewhere in northern Europe? I photograph my peers, the first generation born in the renewed, independent Latvia, and, being inspired from archive photographs, in my images I try to play with over-aestheticized and romantic notions of national belonging. I study archive footage, so that I could then reproduce similar lighting, postures or compositions. I am also interested in youthfulness as a phenomenon. In the old images, we see young people, who are now old, – but at the same time, they represent the idea of youthfulness. I also try to write and I collect excerpts of conversations with the photographed individuals. In this project, I am working with both image and text.

Luīze Nežberte: I, on the other hand, am one of my own subjects. I mostly feel like a spy. I often go to certain places and events, thinking that there will be an opportunity to eternalise something valuable. I am not always interested in the event itself. I document what takes place around me, attempting to understand what it means to be an adolescent.

Kārlis Bergs: What do you think, does your presence affect these events?

Luīze: My presence doesn’t affect the events until the instant I take out my camera. Everyone considers me one of them, a part of it all. I am not very different from the others. My closest friends know that I take pictures. At times, they sense that I am about to take a picture, and then, something does change. Sometimes I do it to distance myself from the day-to-day. I am an adolescent after all; I study at high school and encounter all the situations associated with my age. Photography is a way to comprehend it.

Kārlis: I also keep a distance. When I was shooting for this project, I wasn’t in the stands, screaming for some team. I was mostly interested in observing the spectacle from the side-lines – seeing why the people are doing what they’re doing. I tried to document not the superficial emotions, but the inner world, being as far away from it all as one can be and, at the same time, thinking, what does it mean to be a sports fan. I chose a subjective point of view and documented how people go to games, to lose themselves. When a team scores a goal, euphoria takes over, as if nothing else exists anymore. I use various symbols, which are in the stadium, for example, light, and people’s faces in the state of trance, as well as the weird English weather conditions.

Arnis: But why football, if this distance is rather far-off?

Kārlis: I just started exploring this theme and realized it really doesn’t matter whether it is football or any other kind of sport, where people cheer on, what leads them to this state. I have done rock- climbing, where I also felt as if that instant is all that exists – it’s a phenomenal feeling.

Arnis: Why do you think identity is such a significant matter in Latvian photography? Particularly the collective identity?

Evita: That’s a shrewd question, seeing as the moment you take a portrait, you can start talking about identity. It depends on how the work is interpreted. In my series, it’s not the first and most significant aspect that I contemplate. The work, of course, can be treated in different ways, but, personally, I am more interested in ideas about masculinity – how they come about in, say, a military education setting. The series is not about an individual personality or identity.

Ieva: If you looked at the Latvian culture in general, clearly, the question of what we really are is very relevant. We are in a place, where a struggle occurs between eastern and western influences. We are trying to find a place of belonging. That is reflected in our daily life, in culture, and oftentimes in photography as well. For example, a good example can be found in Ivars Grāvlējs’ exhibition on the history of Latvian photography. It’s supposedly a joke, but his idea was spot-on, discussing the notion that, in many areas, there is no unified history that is specific to us, nor collectively we are all familiar with the notion “we are proud of this”. The question about who we really are, what is our culture and our place in the world, is relevant all the time.

Reinis: It seems to me that identity is often formed in communities and subcultures. Cosplay is also an element, around which identity is sometimes shaped. Many cosplay participants assert that they are shy and introvert people, and by using cosplay as a tool, they find new means of expression.

Ieva: Speaking of communities, it is interesting how the community shapes you and how you shape the community. It’s a constant interaction. Obviously, there are very powerful environments where people circulate, and it affects their personality and behaviour.

Reinis: Yet, they choose the environment, based on their interests and motivations. That is why various subcultures emerge.

Ieva: However, there are communities, which you do not choose, or ones you are born into, for example, a country. You also do not choose whether you are a woman or a man.

Reinis: That’s probably not a community, that’s a society.

Evita: You cannot call it a community, but you could refer to it or define it as an identity.

Arnis: Typically, through our behaviour, style or appearance we confirm our affiliation to a group. We also introduce adjustments in ourselves just to belong to a subculture. The question then arises – what communities do we belong to ourselves.

Evita: People can realise their fantasies, which they probably wouldn’t dare to do in their daily lives. Speaking of Reinis’ project and identity, an aspect emerges concerning the opportunity to distance oneself from daily reality and to live in an imagined perspective, which holds characteristics that one might want to see in oneself. And there are probably many reasons for this.

Reinis: The most frequent reasons are to run away from daily life and office work. These are clichés. The reasons can, actually, be wide-ranging.

Evita: Have you asked them why they might be interested in this?

Reinis: I have spoken a lot with outdoor role players, and they have a wide range of professions. So I did not find a single reason for their choice of a hobby. Though there is one common aspect – many play computer games. The next step is the desire to get into character and become heroes.

Arnis: Speaking of photographer communities, a question arises; can we speak of a unified community? As photographers, we are individuals, and maybe the community is not the unifying element. However, there are students of Andrejs Grants and ISSP students, for whom photography is bonding. Do we also represent a community?

Evita: If we are talking about photography, then it is clear that organizations like ISSP, or maybe Grants’ school create groups of people.

Kārlis: I tend to see the community as a common way of thinking. There are people who focus on sunsets, and others – on photography as art. That’s the biggest difference.

Ieva: I think that a community emerges from common understanding of what is meaningful and what isn’t. We share a similar interest in current events or in particular artists.

Reinis: I do not think you can discuss a community here, as photographers are individualists. Rather, the idea of community could partly stem from the synergy of photographers influencing each other. But I think that the idea of photographers together – it really does not work. I have worked with other photographers, and nothing meaningful comes out of it. Of course, it is a good undertaking, but there is no satisfactory end result, photographically.

Ieva: Many also go to photo festivals, where they can network and socialise.

Arnis: I think that different communities overlap. There is, after all, a connection between all of us. To a large degree, we are interested in similar photography, and we practise it.

Evita: In my opinion, a feeling of community is necessary. Of course, you don’t need someone to stand beside you as you shoot your photographs. But there are so many media, festivals that are outright devoted to photography. It seems that, in comparison to other types of art, photography has a lot more events specific to this medium. Often artists consult each other. When they begin editing their work or building a book, for instance. A support group forms, which can sometimes also become a problem. As, for example, those that mostly consume photography and buy photo books are other kinds of photographers or specialists associated with this medium.

Ieva: Yes, I agree – we lack dialogue between contemporary art and photography. Often these fields are quite separate. For example, there were more than a hundred artists in the main exhibition of the last Venice Biennale, but very few photographers: Walker Evans, Andreas Gursky and maybe someone else. I think the problem is that the photography community is quite closed.

You can read the full discussion in the Latvian Photography 2017, out now and available in most bookshops in Latvia, as well as our online shop.