The Myth of Straight Photography: Sharp Focus as a Universal Language

“The camera reporter makes a major contribution toward greater understanding among the people of all nations. Pictorial reportage is the most universal of all languages. It is an indispensable tool of freedom in these days when so many people are oppressed and personal freedom is restricted in many parts of the world”—so said US President Eisenhower in 1956. 1) Quoted in: Arthur Rothstein, “Communication,” Image 6, no. 3 (1957), 67. “Photography… promot[es] international understanding. But photography is not only a medium: it is also an art. … many artists, who have mastered to perfection the mechanics of their art, are now using photography to express their personal message and thoughts,” so argued Luther H. Evans, the director of UNESCO, in 1956. 2)Luther H. Evans, untitled introduction, Photokina 1956 (Cologne: Photokina, 1956), 27. “Although it is always interesting to get the photographer’s point of view, I believe that pictures actually require little explanation. The photographic image speaks directly to the mind and transcends the barriers of language and nationality,” claimed American photographer and journalist Arthur Rothstein in 1957 (1915–1985). 3)Arthur Rothstein, “Communication,” Image 6, no. 3 (1957), 67. That photography is a language, and a universal one at that, was a popular metaphor in the 1950s. Such a language, as photographers and politicians claimed, could finally unite all the people of the world, because it transcends languages, cultures, religions, political positions, and any other differences. Although today such a belief in the power of photography can seem naïve, in the decade following the end of the Second World War it expressed a hope for a better—peaceful—future. But not just any kind of photography was believed to be a universal language. When Eisenhower, Evans, Rothstein, and many others in the 1950s were talking about photography as a universal language, they arguably had “straight,” documentary photography on their mind. This term is in popular use even now. But exactly what kind of photography is “straight,” and why it was supposed to be so universal?

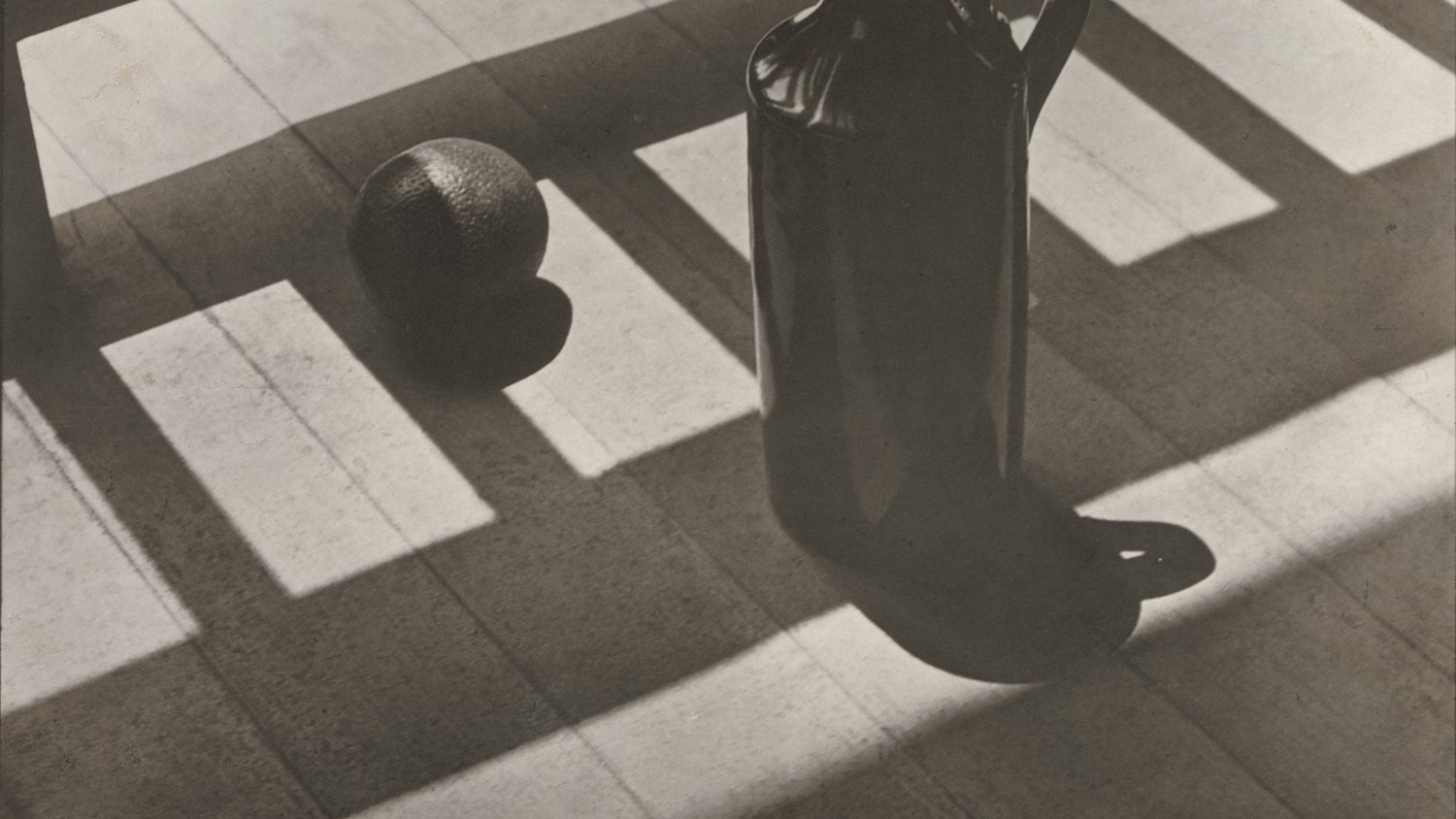

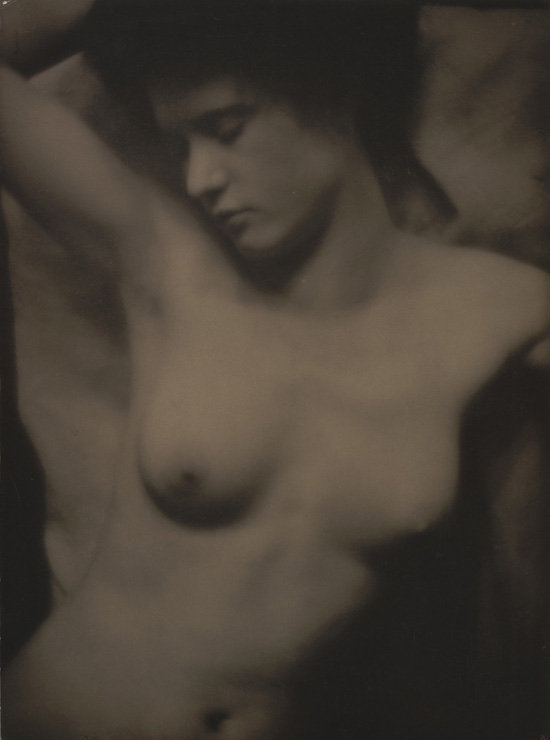

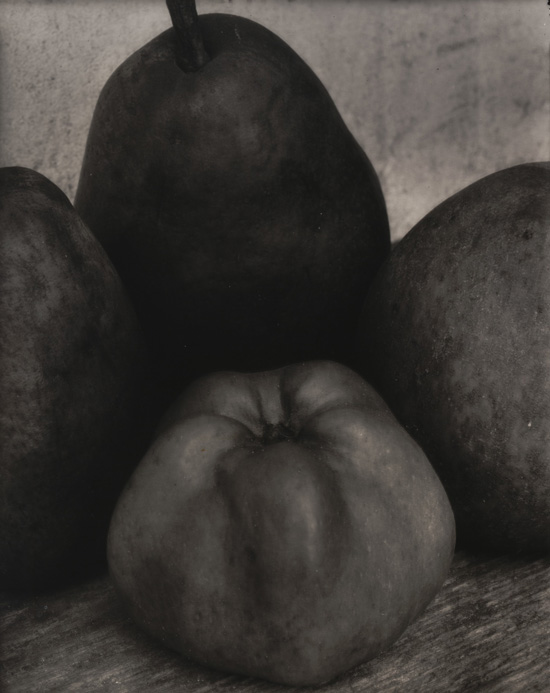

The vague idea of “straight” photography initially emerged as an antonym to pictorial photography, or more precisely, to the Pictorialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Pictorialist photography at that time was typically understood as soft-focus images, handmade prints on textured papers, and romantic or symbolic subjects. The pictorialists’ preferred softness of focus allowed their opponents to criticize their work as “soft”—meaning, by implication, effeminate, unmanly, and queer. As an embodiment of the opposite—and positive—characteristics, they championed sharp focus images, glossy and detailed prints, and prosaic, everyday subjects in industrial or rural settings. The sharpness of the focus here, by implication, conveyed such characteristics as masculinity, manliness, and straightness. This was a clash of two major paradigms in photographic aesthetics, which, for the lack of better terms and deeper theoretical understanding, were discussed in gendered metaphors. The soft focus was associated with femininity and thus—unsurprisingly, despised; while the sharp focus was associated with masculinity, and thus—celebrated. Soon it was taken for granted that a sharp focus, deep depth-of-field image is the only—and the natural—way to do photography. The word “straight” as such does not clarify anything in relation to photography, but it has become a vessel for all kinds of qualities and ideologies. “Straight” has been used as an expression of masculinity, heteronormativity, and patriarchy, the term manifested a desire for clarity, detail, objectivity, it signaled a preference for materialism over fantasy, romanticism or spiritualism, a preference for industrial production over craft, or a preference for deep depth-of-field over the flatness effect of an image. By itself, sharp focus, however, is neither good nor bad, and it does not signify a better—more artistic or creative—approach to photography than soft focus. The artificial and gendered antinomy of soft and sharp focus is anecdotal, but it points to significant differences between two major paradigms of photography that emerged in the 1910s.

The iconic figure instrumental to this gendered clash of focuses was American photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946). Apart from making some of the most well-known American pictorialist works such as Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893), he was also one of the leaders of the late nineteenth-century pictorialist milieu, founder of the Photo-Secession group (1902–1917) and editor of its magazine Camera Work (1903–1917). But Stieglitz grew to renounce Pictorialism with the same zeal as he had promoted it. All major histories of photography will tell you that Pictorialism as a historical art movement ended around 1917, with the publishing of the final issue of Camera Work which Stieglitz dedicated entirely to works by Paul Strand (1890–1976), an American photographer often considered to be a pioneer of “straight” photography. Strand’s image White Fence (1916) is one of the most often reproduced examples. Stieglitz’s photograph relies on atmospheric effects to create a romanticized impression of a snowy day in the streets of a great, wealthy city. Strand’s image, meanwhile, brings to our attention a close-up of crackled paint on a wooden fence in an unremarkable, unrecognizable rural setting.

Among the most influential champions of the idea that this “modern,” sharp-focus photography is to replace “outdated,” soft-focus Pictorialism, was Beaumont Newhall (1908–1993), American art historian and curator, who in 1937 wrote a seminal history of photography, The History of Photography From 1839 To the Present Day. The book grew out of the exhibition Photography 1839–1937 that he had curated at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1937. Newhall’s book continues to be in circulation even today. All major American and Western European histories of photography that have appeared since then are largely based on Newhall’s argument. 4)For an Euro-centric example, see, for example, Michel Frizot, ed., A New History of Photography (Köln: Könemann, 1999), for a US-centric example, see Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History. 3rd edition (Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011). His book is critical of Pictorialism for its alleged imitation of painting (which itself is a sweeping and generalizing claim, because Pictorialism was not a homogeneous movement). Newhall largely follows Stieglitz who described Strand’s works in Camera Work as “brutally direct, pure, and devoid of trickery.” 5)Alfred Stieglitz quoted in Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 150. This is the kind of terminology on which Newhall sets up the antinomy between Pictorialism and “straight” photography which has shaped most of the historical writing on twentieth-century photography.

Today, we can admit that this historical narrative is extremely narrow and limiting. Newhall was writing an art history of photography based on the work of a few “great masters” in the US and Western Europe. His history overemphasizes the role of French photographer Eugène Atget (1857–1927) as the founding father of “straight” photography. Atget’s work, however, would have remained virtually unknown if the American photographer Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) would not have purchased his archive and brought it to the US. From Atget, Newhall builds a genealogy of American photographers who pursued “maximum detail, definition, and brilliance”—this is how he described the “straight” work of another former pictorialist, Edward Steichen (1879–1973). 6)Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 156. Among Newhall’s heroes—“straight” photographers—are Paul Strand, Edward Weston (1886–1958), and Ansel Adams (1902–1984). In a seminal article about the historiography of photography, Douglas Nickel has noted: “Newhall saw his delineation of history leading directly to what he considered the best work being done by his modernist peers. Their aesthetic idea was monolithic: sharp focus, a full range of tones, clarity of detail, no darkroom trickery.” 7)Douglas Nickel, “The History of Photography: The State of Research,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 3 (2001: 548–558), 552. But why must we hate “darkroom trickery”? Who said that sharp focus is intrinsically better than soft focus? What is wrong with heightened contrast, flatness effect, blurred motion, and so many other, non-straight elements of photographic aesthetics? Why should we assume that “straight,” documentary photography is the universal language?

It was even more reasonable to ask such questions in the 1950s and early 1960s, when equally popular was the idea that abstract art, and especially painting, is also a universal language. It was another way to express a longing for peace and understanding—abstract art does not depict anything, thus its perception does not require any knowledge of a particular culture, and it can be understood by anyone, anywhere, anytime. This was another idea of a visual language that would transcend cultures, languages, religions, and political beliefs. Yet abstraction in postwar photography has not been widely recognized as a universal language. Its existence has been acknowledged, but it has never been praised as highly as abstraction in painting. It has remained largely in the shadow of “straight” photography. Thus, for example, two exhibitions in the Museum of Modern Art, New York showcased abstract, non-representational photography in the 1950s and early 1960s: Abstraction in Photography (1951) and The Sense of Abstraction (1960). They acknowledged that abstraction is a modern and creative aspect of photographic art. But non-representational, non-straight photography has only recently begun to gain more visibility and scholarly attention. 8)See, for example, Lyle Rexer, The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2013); Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 (Amsterdam: Focal Press, 2014); Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (München: Prestel Verlag, 2016). Nevertheless, scholarship on postwar photographic abstraction comes with its own reservations. In postwar painting, abstraction was glorified as the epitome of an artist’s creativity and experimental and avant-garde aspirations. But here, in the context of photography, abstraction is always accompanied by a certain skepticism and even fear. As a result, more scholarly attention has been given to documentary, narrative work than to experimental, often non-representational work. Two examples are Brazilian Concrete photography and the Subjektive Fotografie that originated in West Germany of the 1950s. Both artistic movements and their achievements are still marginal and undertheorized.

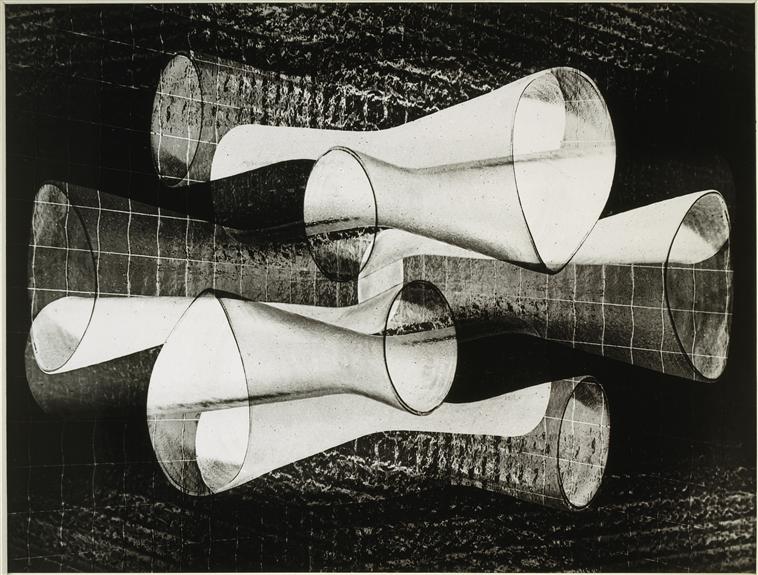

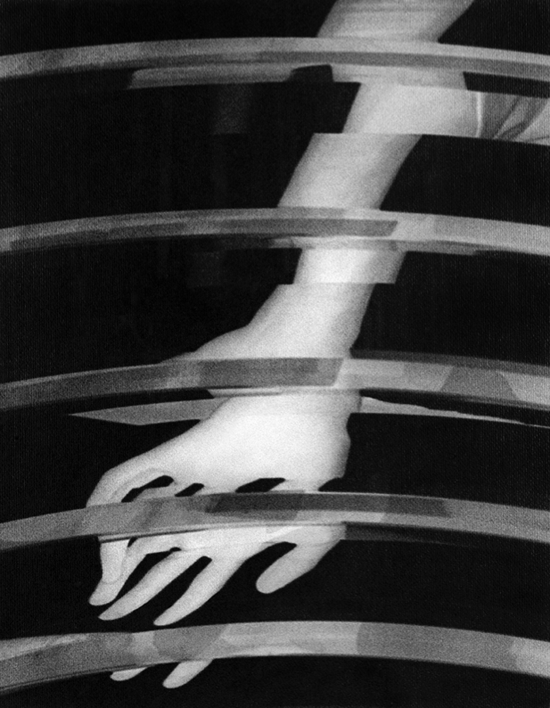

Envisioned by Otto Steinert (1915–1978) as a revival of the Weimar Republic avant-garde photography of the 1920s, Subjektive Fotografie explored means of photographic expression such as blurred motion, multiple exposure, dark tonality, and high contrast, at times aiming at abstraction and achieving purely geometric effects. Steinert and his followers, united in the group fotoform between 1949 and 1958, were concerned with finding novel—and by that they often meant non-straight—ways of depicting everyday reality. The resulting images were supposed to express the author’s subjective experience. Most of Subjektive work is figurative, but definitely non-straight thanks to the use of a variety of photographic effects and techniques such as optical distortion, reverse print in negative, multiple exposure, and unusual angles. But by the end of the 1950s this movement was marginalized by viewers and oppressed by the community of fellow photographers in West Germany. Nobody can understand Subjektive Fotografie without reading the authors’ comments—that was the popular response. Meanwhile, “straight” photography seemed so much easier to understand without an explanatory caption, mainly for the simple reason that viewers were able to recognize what was depicted.

While experimenting with non-representational photography, Rio de Janeiro-based photographer José Oiticica Filho (1906–1964) was completely unconcerned with the documentary function of photography. Instead of camera work, he was interested only in darkroom work. Against Henri Cartier-Bresson’s popular concept of the decisive moment, Oiticica Filho put his own concept of fundamental time by which he implied the long process of darkroom work. 9)Paulo Herkenhoff, “A trajetória: da fotografia acadêmica ao projeto construtivo,” in José Oiticica Filho: A ruptura da fotografia nos anos 50 (Rio de Janeiro: Funarte, 1983), 15. “Free yourselves from the camera and try to dominate it with your brain,” wrote Oiticica Filho in 1955. 10)José Oiticica Filho, untitled, in ABAF Journal, December 1955, quoted in: Andreas Valentin, “Light and Form: Brazilian and German Photography in the 1950s,” Konsthistorisk Tidskrift/Journal of Art History 85, no. 2 (2016: 159-180), 164. Among his techniques was a multi-step process of his own invention: he made a drawing or painting, photographed it, enlarged the negative, made a positive print on a transparency, then superimposed it onto the original drawing, photographed it again, and so on. For him, the sophistication of the abstract aesthetic form was more important than the informational value of the photographic image.

Photographers like Oiticica Filho or Steinert challenged and questioned the perception of photography as such. They wanted to use the photographic process for creating images that do not function only as a record of the visible reality. Their images aimed to be reflections of their makers’ inner world, not depictions of the outside world. But postwar non-representational photography did not meet popular expectations of what the function of photography should be. By rejecting representation, it challenged and negated the primary and most obvious purpose of photography. As mainstream understanding goes since the 1950s, photography’s sole aim is to create “straight,” realistic, documentary depictions of the visible world. This function of photography has been internalized by historians, theorists, and museum curators worldwide, and their preferences have marginalized all other kinds of non-straight photographic practices—including Brazilian Concrete photography and West German Subjektive Fotografie. What initially started as a debate among a few passionate photographers about their preference for soft or sharp focus, eventually turned out to shape much of twentieth-century photography.

___

This article has been made possible by a support from the US Embassy in Latvia

| 1. | ↑ | Quoted in: Arthur Rothstein, “Communication,” Image 6, no. 3 (1957), 67. |

| 2. | ↑ | Luther H. Evans, untitled introduction, Photokina 1956 (Cologne: Photokina, 1956), 27. |

| 3. | ↑ | Arthur Rothstein, “Communication,” Image 6, no. 3 (1957), 67. |

| 4. | ↑ | For an Euro-centric example, see, for example, Michel Frizot, ed., A New History of Photography (Köln: Könemann, 1999), for a US-centric example, see Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History. 3rd edition (Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011). |

| 5. | ↑ | Alfred Stieglitz quoted in Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 150. |

| 6. | ↑ | Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 156. |

| 7. | ↑ | Douglas Nickel, “The History of Photography: The State of Research,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 3 (2001: 548–558), 552. |

| 8. | ↑ | See, for example, Lyle Rexer, The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2013); Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 (Amsterdam: Focal Press, 2014); Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (München: Prestel Verlag, 2016). |

| 9. | ↑ | Paulo Herkenhoff, “A trajetória: da fotografia acadêmica ao projeto construtivo,” in José Oiticica Filho: A ruptura da fotografia nos anos 50 (Rio de Janeiro: Funarte, 1983), 15. |

| 10. | ↑ | José Oiticica Filho, untitled, in ABAF Journal, December 1955, quoted in: Andreas Valentin, “Light and Form: Brazilian and German Photography in the 1950s,” Konsthistorisk Tidskrift/Journal of Art History 85, no. 2 (2016: 159-180), 164. |