Deep Springs

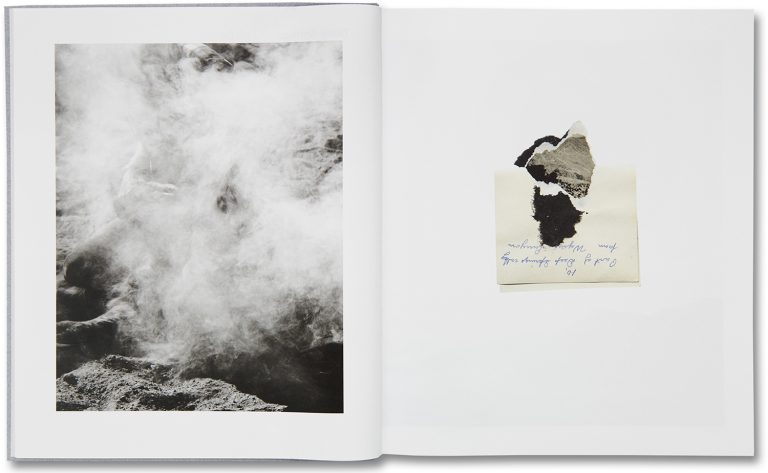

“The greenest grass is in the deepest mud” – this evocative phrase written on the back of a photograph captures a feeling that is present throughout Sam Contis’s book Deep Springs (MACK, 2017). Deep Springs is the name of a valley in California which is also the home of an innovative educational institution. Founded in 1917, Deep Springs College combines a rigorous academic programme with farm and ranch work. The school is located in the desert and is isolated from the rest of the world – the nearest gas station is an hour’s drive. The student body consists of 26 young men, who during their time there have to learn how to maintain their small community in a ruthless environment – the desert of the American West. Contis spent four years in the valley, photographing these young men and their lives.

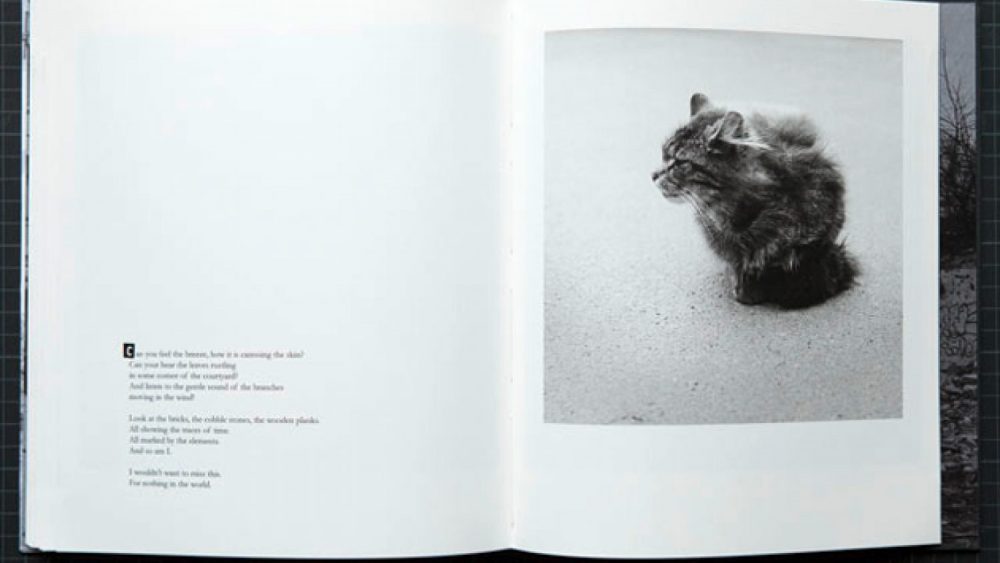

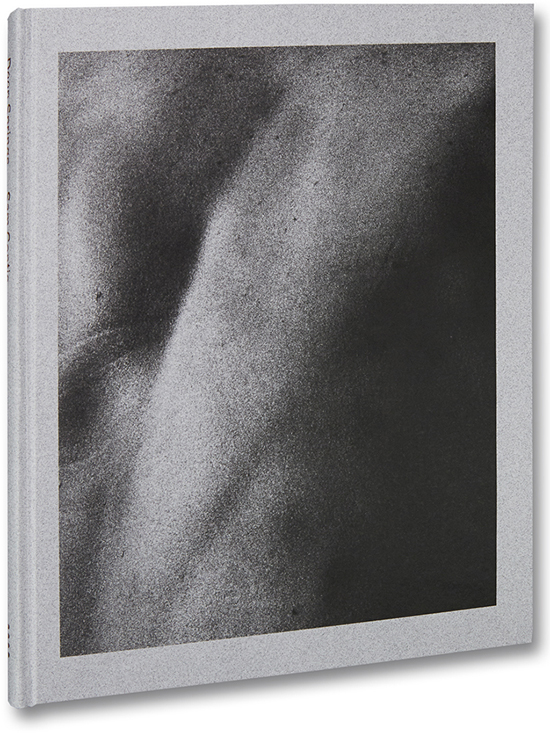

The cover of Contis’s book is a grainy close-up photograph of what seems to be the birth-marked back of a man, the skin sinking down between his bones. The image is almost abstract. Most likely what we see is the back of a human body, but it is also reminiscent of a sandy desert landscape with hills and valleys. The contrast between the bodies and the dry terrain surrounding them is ever-present in Deep Springs. The bodies are thriving and sentient while the land around them is dry and unforgiving, nothing grows there unless you really force it to. Technology is evolving at an unprecedented pace, and soon a connection with reality as a tangible entity might become optional, but the young men of Deep Springs are still shaped by their environment as much as they are the ones shaping it.

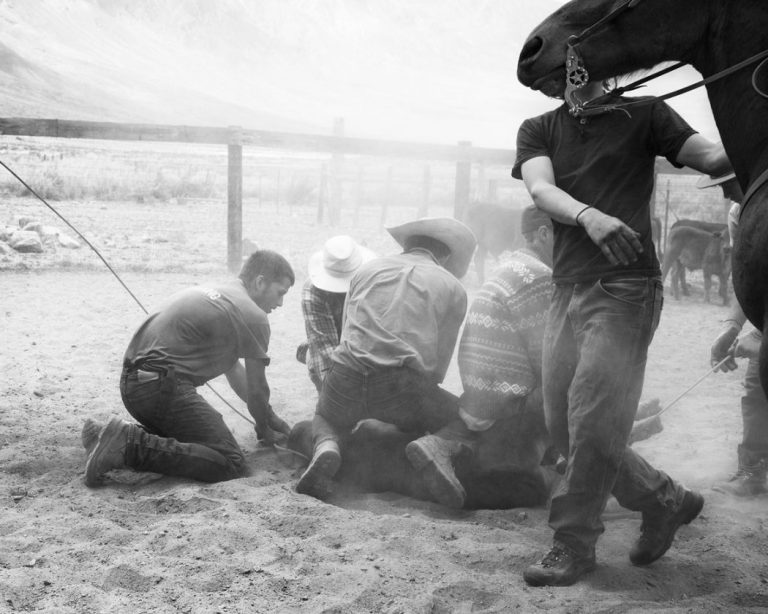

In several interviews Contis points out that the project goes beyond the geographical location where it was shot. While it is a story set in this specific place, it raises questions about masculinity, identity and its representation. For the artist, Deep Springs has become a field of investigation to re-evaluate ideas regarding the American West and the myth of the cowboy, the ways in which this has been represented in popular culture and what it means today.

The cowboy is a symbol of a certain traditional understanding of masculinity. He is handsome and capable; he rides a horse, and lives in the dry desert landscape, isolated from the rest of society – this demands a certain emotional and physical self-sufficiency. In the 1980s Richard Prince re-photographed Marlboro cigarette ads. The cowboys in these images were so epic that they even coined the term Marlboro Man – the company didn’t even have to directly mention cigarettes on their advertisements anymore, everyone knew what they represented. Prince says he was inspired to make this work when he realised that he never sees cowboys in real life, but in magazines they appear all of the time. These were the cowboys that he began to photograph. After cutting out the text from the images, Prince exhibited the cropped photographs. The work made him famous – it commented on both the appropriation of imagery in art as well as the stereotypical notion of the cowboy. The cowboy as a symbol of the American West, romanticised by advertisers and popular culture, is a mythological image that exists in the collective subconsciousness, but is seldom seen in real life.

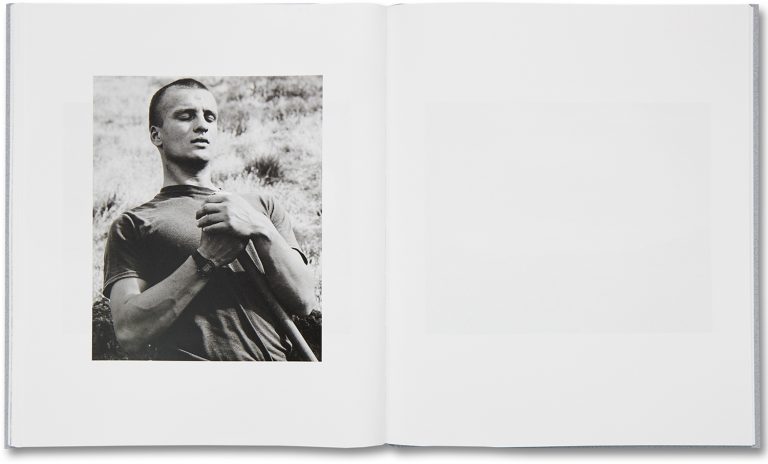

Contis is also interested in the cowboy as a cliché of what it means to be a man. Even though the subjects of her photographs often wear cowboy hats, and we see them performing typical cowboy tasks such as riding horses through a desert valley or rounding up cattle in clouds of dust, they’re not epic Marlboro Men. The work is a physical and emotional close-up of the young men in Deep Springs. We often see them doing non-monumental, everyday things, such as reading a book or taking a nap. In many instances their bodies are covered with flies which is likely to happen when it’s scorching hot outside and the work is strenuous. Every now and then there is an image of their hands. Their hands can do many things – control the horses and cattle, gently hold a small branch with a caterpillar crawling on it, cut through the fat of a dead animal, get dirty with motor oil from working with an engine, hold a piece of fabric with animal blood on it, cut plants in the garden with blue scissors. In an interview Contis mentions having shown the book to a graduate of the school who was there in the same time she was making the work: “He was looking through it and could immediately recognise all the hands, necks, backs, and shoulders that appear—he could immediately say who they belonged to. He said he had never been so intimate with other people’s bodies before his time in the valley.”

At its core, the myth of the cowboy is about being untouchable and self-sufficient to an extreme. The young men of Deep Springs are not that. They are not immune to pain as the epic Marlboro Men, but it is exactly their vulnerability that is attractive. “There is room for many different versions of masculinity here, which are not defined by gender stereotypes,” Contis says in another interview, speaking about the environment at Deep Springs. In a recent article in The Atlantic, Sarah Rich, whose son decided to go to school wearing a dress, points out that stereotypes that “boyish” girls are badass while “girlish” boys are embarrassing, are still very much present, and that they are telling kids that society values and rewards masculinity, but not femininity. Among many things, Deep Springs serves a re-evaluation of those ideas. In the book there is a photograph with one of the students lying in the grass wearing a denim dress. Another image is a close up of someone’s neck – we see the young man’s Adam’s apple, sparse facial hair on his chin and long, dark hair on the side. Some of the young men in the photographs have a certain femininity to them, but it’s definitely not a signal of weakness. Quite the opposite – Deep Springs questions the myth of the cowboy as a epitome of masculinity by capturing the daily life of these young men who have real life cowboy tasks. The work reveals the myth more for what it is – a symbol of isolation in a deeply emotional sense, while also proving that there is something very open about the way these young men live in this very remote environment. So, even though we don’t get to see the other side of the photograph, the words written on it hold true – sometimes the greenest grass is in the deepest mud.