Simon Menner

Simon Menner (1978) is a German photographer, who is interested in the image capacity to manipulate with the perception of audiences. Whether they are snipers in ambush photographed by himself or images found in the channels of Islamic fundamentalists, his works share an interest in the significance of images in military conflicts and the impact left on public awareness. Menner has studied at the Berlin Art Institute. He has participated in numerous shows all over the globe. His photo series The Last Image Before the Blast will be offered to audiences in the Riga Photomonth exhibition Eating Pineapples on the Moon, which will run from 15 May to 16 June at the Museum of Occupation of Latvia.

Do you remember what triggered your interest in the images of conflict, perception and surveillance?

The single work always comes from a common general interest and that remains quite steady. There might be a spark though, that triggers my urge to look at something quite specific. Often, that is just a single sentence I read somewhere. For my work on the Stasi it was like that. I had read a lot on surveillance and in one text there was a short note that the Stasi utilized Polaroid cameras to hide their tracks, when searching private apartments. My reaction was “I would love to see them”. And thus a three to four year research project was started.

In general, I am very interested in the ways our perception is being utilized against our interests. Fear has become a key weapon. If a suicide bomber blows himself up, on the subway in London, my mother, in a small town in southern Germany, is afraid. That is strange and fascinating, especially since she has never been in London, nor, to my knowledge, has she ever been on a subway. Why is that?

On a fundamental level, the sniper, hiding in the forest, the suicide attacker with his hidden explosives, and the agent that uses disguises to spy on regular citizens, are strangely connected. All of them claim to pose an invisible threat. All of them try to pose as something far more potent than they actually are. A suicide attacker might kill people, sharing the train with him, yet normally my mother should be far beyond his reach. While the mechanisms are extremely simple, they work, and my mother is scared.

What was the process like when working on The Last Image Before the Blast?

I tend to collect a lot of material, before realizing what the actual interesting part might be. At first, I found it strange, that these videos of terror attacks end up on the Internet. Sure, in a time, when everything is uploaded, that makes sense, yet it felt strange to me. After a while, my urge to collect more was driven by noticing that something fundamental was changing. The first videos I found were all either taken by surveillance cameras or by regular bystanders who just happened to film, when the blast took place. After a while, more and more videos were released, where the camera was part of the attack. People already knew that an attack was going to happen, and the camera was pointing in the right direction. This has to be understood as a fundamental shift. The videos of these attacks were not accidental anymore, but many of these attacks were performed to create images.

It was not the explosion or violence that interested me the most, but the apparent tranquillity just before. This is why I chose the last frame before and not after the event. The viewer is left clueless on where the attack might take place, or what might be exploding.

Has your work ever been censored?

It feels strange, but yes. Shortly after I started working intensively with material, sourced from different Islamist groups, I wanted to print a small booklet with some first results of my research. The printer refused to print it. Which is strange, because even though I am working with material, that is absolutely brutal and inhumane, I am not revealing any of the violence in my projects. Some people are shocked by the works I am showing, but that has nothing to do with me showing blood and violence, it is more the absence that becomes shocking. The void, where we know the violence must exist. When talking to some of the people at the printing company, they could not point to something that could be used as an excuse for their decision, apparently it was more of a gut feeling than anything else. Even though I did not print the booklet in the end, it convinced me, that I am on the right track and that my approach is working.

I am trying hard not to fall into the trap of self-censorship. In Germany at least, everything I am doing is legal. I am allowed to look at Islamist propaganda – even if it depicts violence – and I am even allowed to collect it. I might be considered distasteful, but that is it. Sharing the raw material would be another story. I think that it is crucially important that researchers and artist can have access to this kind of material to make sense of it. To dissect it. To educate others. This is why, for none of my projects, I ever hide my tracks online. I am deliberately not using any anonymization tools. If law enforcement feels the need to look into my activities? So be it. Self-censorship is extremely dangerous to society and an open discourse. So, lets avoid it as long as we can.

What was your experience like when shooting in Latvia?

The only project, I was working on in Latvia, was for a series in which I photographed snipers of the Latvian Armed Forces. That experience was amazing though. The people I was in touch with were all extremely helpful and enthusiastic.

What are you working on at the moment?

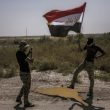

While the stuff I am working on at the moment comes, in part, from my research on terror propaganda, it is somewhat different. Starting from an observation that the civil war in Syria and Iraq has a lot of visual parallels to ancient wars, I am trying to show that warfare today should be understood as a visual continuation of much older conflicts. On satellite images of Syria, many towns and cities can be found that surrounded themselves with city walls. Not from stone or bricks but made of sand. Tall building have replaced the watchtowers of the middle ages. Checkpoints are the city gates of today. And grain silos or power plants are fought over like ancient keeps. It is striking to see these structures right next to archaeological sites that are thousands of years old, but that appear so similar.

But the parallels I am trying to draw go beyond architecture. The gestures and pathos in many of the propaganda videos, released today, seem to find their inspiration in the claims made during the time of the crusades. And not just on the Islamist side, everyone seems to join in. It all becomes this unchanged medieval struggle,] that tries to find its visual valve in social media platforms of the 21st century.

Might sound vague, but that is what I am currently working on.