The Fulcrum of the Perestroika Generation

Review of the solo exhibition of London-based Estonian artist Maria Kapajeva Dream Is Wonderful, Yet Unclear, open until 30 June in the Latvian Museum of Photography as part of Riga Photomonth 2019 programme.

The first thing that catches my eye is the transformation of space – even though the Museum of Photography has never truly cut the cord to our common past, its ambiance has indeed become more Sovietically saturated. Black-and-white images of factory equipment from the 1980s are hanging over the staircase quite unnoticed. They seem to be forgotten, abandoned artifacts from an earlier era or maybe something belonging to the default historical museum display. Banners glorifying peppy workforce and technocratism as well as cozy information board corners were so indispensable to Soviet Interior Design that we, who have lived in that system, have become trained not to pay any attention to their constant presence. No wonder that at first I overlooked these images – elements of the exhibition – noticing them only with my peripheral vision and unconsciously interpreting them as “Soviet leftovers”. I grew up during the period of denial of Soviet ideology, after all, and so learned to delete such “leftovers” from my perception – similarly to how our history teacher guided us to cross out any sentences pertaining to the Old Ideology in our textbooks at the beginning of every new school year. When I was a child, the only explanation to why there were still old black-and-white photos picturing Soviet slogans or builders of Communism on the wall, was – euroremont, the coveted Western-style remodeling, has not been done yet. It may surprise you, but ignoring is a rather simple act. Even an impressively tall building, such as our Monument of Freedom had once somehow become invisible to everyone – as if it had simply vanished. Most of the Soviet era photo archives will serve as evidence to that. However, when we decide to ignore an idea, something else may get lost or become overlooked – namely, the people themselves and the human values that remain behind the artifacts of any ideology.

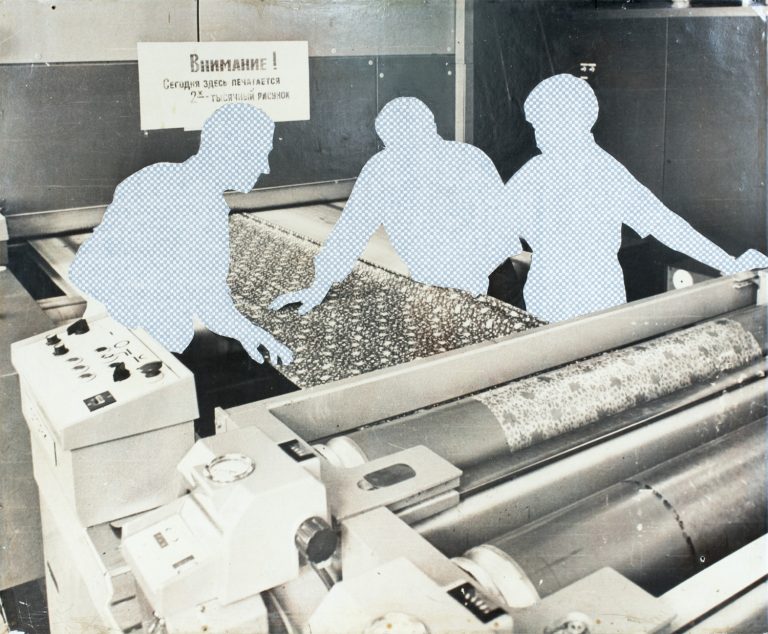

This seems to be one of the central ideas photographer Maria Kapajeva wants to highlight in her exhibition. Filling in the spaces left by cutting out human figures from posters with Photoshop checks and crisscrosses, she makes a unique pattern of every person’s emptiness. Kapajeva uses different patterns as symbols of serial production and proletarian society and the fulcrum of the story she wants to tell – of the once thriving Krenholm textile factory in the Estonian-Russian border city Narva. Almost all Narva women used to work in this factory, as did many of Narva men. In the 150 years of the factory’s existence, multi-generational textile workers’ families, even dynasties were came to be; seemingly immutable rites of work, values and traditions were established – only to perish together with the Soviet Union, leaving thousands of people without work and a reference point in life. By using testimonies and private photo collections of the former factory workers, the artist interweaves her personal story about her own family, childhood dreams and life ideals with the story of the community, a story of the disintegration of the old value system and the search for new identity. Decorative patterns are an effective common denominator that frames this complex theme in a precise conceptual narrative, and unexpectedly brings about a number of keywords shared by manufacturing industry and social organization theories: model, rapport, remnants, cutbacks, etc. Wordplay in the titles of individual artworks is clearly deliberate and of great importance to the artist.

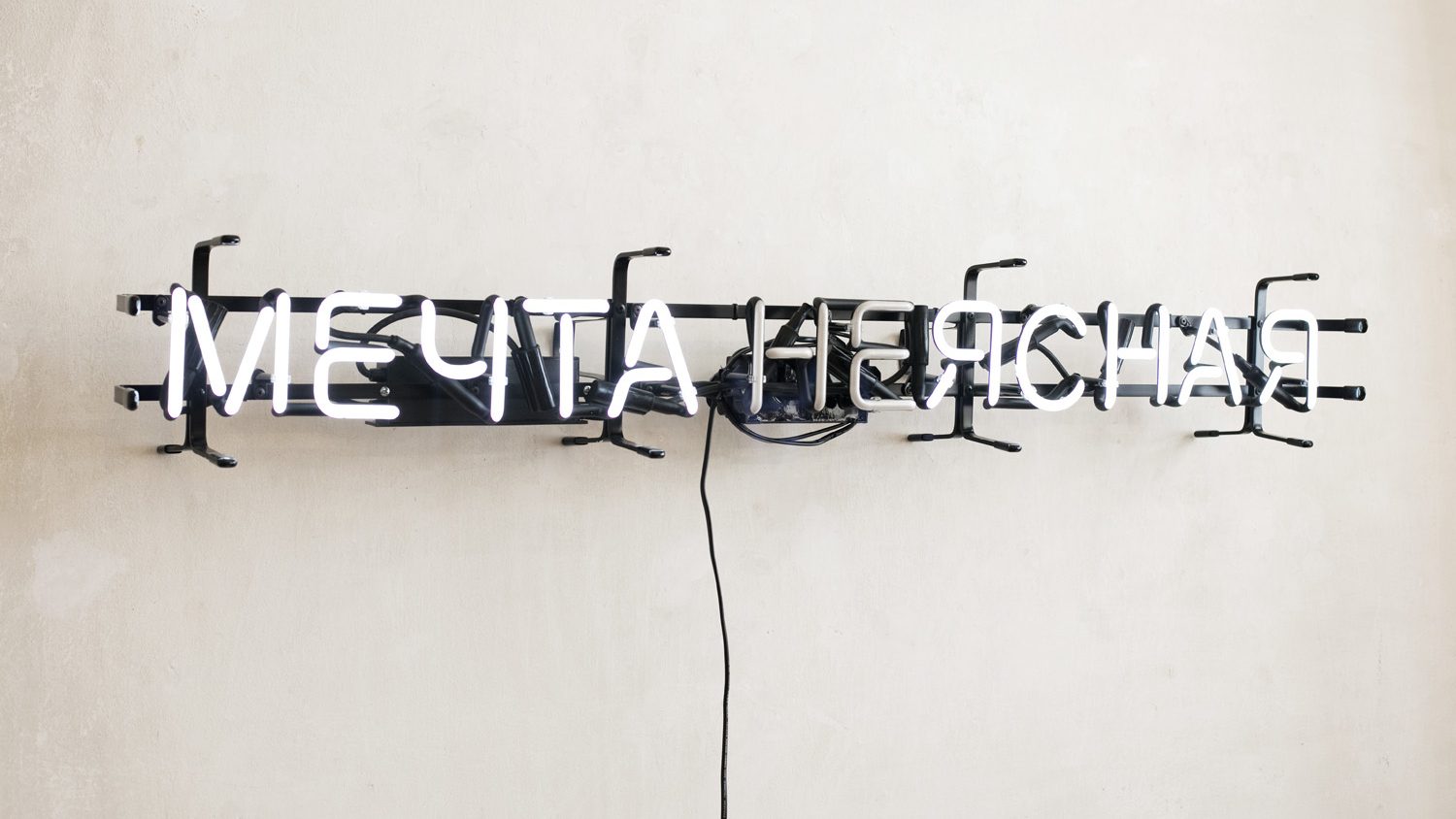

Like in the case with the photo collages displayed over the staircase (Cutbacks), Maria Kapajeva uses very direct metaphors through her exhibition. The person cut from the photograph, the prefix in the neon inscription “Dream is (Un)clear” flickering on and off (light sculpture Dream is (Un)clear), the pattern elements queuing in neat lines not dissimilar to the thousands of factory workers (the fabric has been marked with the stamp once used to indicate a defective product a number of times equal to the number of workers that were laid off – the work 12,000), the two screens next to each other showing, in parallel, two very different movies – The Bright Way (1940), an upbeat Soviet propaganda musical, the Cinderella story of a diligent textile mill worker, culminating in the lavishly decorated assembly hall of the factory – and the video shot by Maria Kapajeva herself: bewildering choreography of Estonian dancer Maarja Tõnisson in the abandoned factory spaces, as she attempts to mechanically imitate the shots from the film with the help of the director’s remarks, without any mental connection to the original film (video installation The Bright Way), and, after all, the very title of the exhibition, Dream Is Wonderful, Yet Unclear (the censored lyrics from the song March of Enthusiasts from the movie The Bright Way (1940)).

These declarations are straightforward and quite exalted, which suits the Soviet aesthetics, but Kapajeva doesn’t stop at the level of shallow cliches, her dive is much deeper. A personal, profoundly emotional, sentimental, humane and painful thread runs through all of her work, reminding us of the lot of women (mainly); the attentive and selfless touch of the author is present in every centimeter of her work, in every hand-painted flower, every cut-out photograph and stamp, manifesting the personal attention she has dedicated to each individual of the collective. The theme is weighty and very broad, therefore I appreciate the laconic expressivity of the exhibition that is attained by a few carefully chosen indicative and symbolic pillars holding up this complex story without speculation, without political critique, but focusing on the people and contemporary values.

The exhibition works not only mutually and conceptually complement one another, each one is impressive by itself. The site-specific design pattern that the artist paints on the wall in each exhibition venue is a striking project and its display in Riga certainly is a special event of the Photomonth. It can be easily missed – the wall covered in tiny golden flowers merges so well with the space that it becomes almost indiscernible. Empty wall, empty space, nobody would pay any attention to it if not for a discreet sign, indicating that somewhere here an artwork should be located. This is one of the most excellent and powerful allegories of the “invisible” labor of women that I’ve ever seen: from taking care of the home, putting fresh flowers on the table, ironing children’s trousers, to countless professions that are considered neither profitable, nor heroic – still, someone patiently strives in them. The tiny golden flowers that rhythmically cover the wall of the exhibition space, is the original design of the artist’s mother who was a textile designer at the factory, a high-level professional sacked in the first round of layoffs. Titled Mapping My Mother, the work wistfully interlaces the artist’s longing for her mother, the wish to follow in the parents’ footsteps and be proud of them, with the intergenerational conflict – the inability to adhere the values of the previous generation, explored also in another work on display – Failed Rapport (1987/2017), as well as an attempt to understand them and their particular cultural identity.

“We all knew somebody [from the factory],” the photographer tells in a public discussion of her hometown Narva, where she was born in a Russian-speaking family in the late years the USSR. Every citizen of the former Soviet republics could say something along those lines. Since she lived in the countryside of Latvia, my impression of my granny is romantic, folksy and clear – at least on the surface; however, the period of her life characterized with the word “factory” seems inaccessible and alien. Kapajeva finds the most accurate depiction for this feeling of alienation towards the women in her family in the awkward motion of dancer Maarja Tõnisson as she puts on the factory worker’s kerchief in the video installation The Bright Way – the motion signaling ineptness and resistance to perform this habitual gesture of the previous generations. There is also something very familiar in the facial expression of the dancer – the grimace, adapted in the childhood when the mother sneered in derision of something you didn’t know or do that was supposedly generally known or done. Perhaps, the literal expression of the generational divide – emptiness and lack of understanding, which demonstratively contrasts with the March of Enthusiasts and the performance of Lyubov Orlova’s energetic, motivated stakhanovite in the adjacent screen. Our generation seems suspicious, doubtful and lethargic.

Symbolically, the exhibition includes also Viktors Lisicins’ photograph of a local Riga knitter from the museum’s collection – to underline that this issue concerns a much larger territory and society than just the city of Narva. If we focus on the role of women, the artist’s observations relate also to the women outside the post-Soviet sphere. Kapajeva’s ability to catch the audience in the trap of their own past and denial is extraordinary. Mapping My Mother pushes the spectator into an active role – I recoil at the thought that, at first, I walked past this artwork – that just a moment ago I was the one who didn’t notice the “woman’s labor”. That all of this concerns me too, that I am hanging in mid-air on the same bubble of unresolved, disregarded and blurred values and relationships – the owner of plagiarized, not inherited, identity, that I’d rather avoid discussing out of shame, just like I wouldn’t want to look at the cartoons of Donald Duck I drew in the primary school, hidden away under the bed.

Unlike me, Kapajeva has the courage to bring to light her own childhood textile design of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck that her mother refused to propose for production. The artist has symbolically attained her childhood dream by printing the fabric and creating a skirt with her childhood heroes – the capitalist cartoon characters. I’ve always tended to consider myself, my family tragedies or failures on the individual level (it’s too hard to extrapolate), but Kapajeva is able to easily and truthfully point out the collective similarities not only in the Soviet, but also in the Perestroika Generation: the same wallpaper, the same cartoons, the same frustrated mothers and aunts, the same recognizable unemployed old ladies, grumbling about their problems that are too heavy and hard to define for anyone to pay real attention. With this exhibition Kapajeva attempts to give voice to a huge, undervalued social group – the female factory workers that lost their jobs in the era of political upheaval, when they were already middle-aged, and never found a new footing for their lives. She tries to retrieve some meaning for the lives of these people, to honor the weavers of her hometown, by displaying on the walls idiosyncratic phrases, which at least in my childhood I relegated to background noise or a remnant of the past not worth paying attention: “It’s hard to work three shifts”, “We were honored, we were respected”, “I’ve 10 years added to my retirement benefits because of hazardous work”, “I gave 40 years of my life to the factory”.

We speak unjustifiably little about them/us as a group, about the Soviet experience and the part of our identity that we have so quickly remodelled. But now we have reached the time when the slapdash remodel is starting to disintegrate, and we have to admit that tacking on some plaster boards is not a sustainable solution. We need to take them off again and look what’s been left behind them.

The mechanical clatter of the slide projectors in the museum’s upstairs hall remind of the noise in the factory’s loom workshop. The slides show individual portraits, carefully cut out from group photographs, to quite literally demonstrate that any group is made up of individuals, each with their own destiny. This is Kapajeva’s monument to everyone who worked in the relentless routine of Krenholm factory. To people who believed that they are restoring the world ravaged by the war to fulfill the dream of the bright future – wonderful, yet unclear.

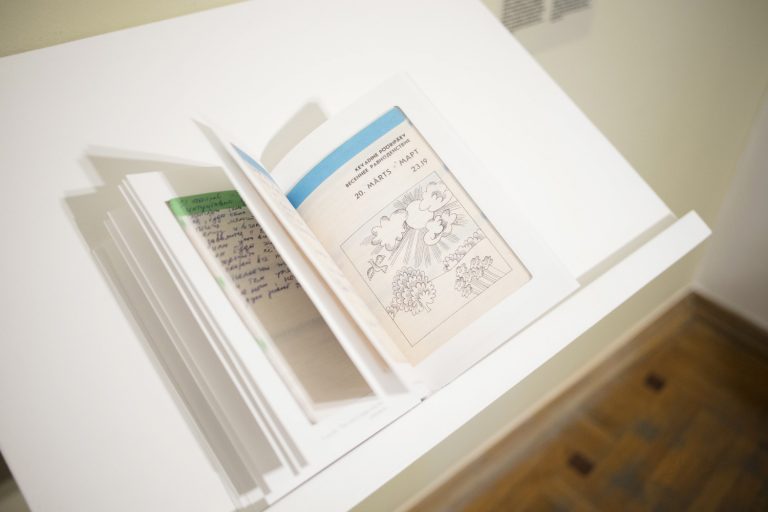

The most unsettling, however, is a small exhibit in the corner of the second hall: the authentic personal diary of a female factory worker. In the context of the exhibition each page seems to be a veritable work of art – an illustration not only of woman’s role in the automated factory system but also of the female identity as a whole. In the same breath, with the same intensity the entries switch from professional ambitions to family and domestic life, sexuality and sentimental musings: surpassing yearly production quotas, purchase of wallpapers, clothing patterns, dodging impregnation, diets, weight, lyrics of the song Forget Me Not and an abrupt entry – “today, I’m turning 42” – words that for some reason seem to implore “who am I really?”

As I head for the exit, I notice another medium-sized color photography in the staircase – a group photography of the kind that sometimes adorns the walls of corporate offices or institutions (Group Photo. 2017). Coming in, I didn’t notice this photograph either. I do not tend to look at group photos, unless I’m looking for a face of a friend or relative. At the monumental factory gate its former workers have gathered perhaps for the last time. Mostly women, aged 60 to 90 – as if in front of a bread oven or a womb that brought forth this generation, once determined their routine and collective values, gave daily bread and ideas. And who am I really? As I leave I’m struggling to keep my usual expression of resignation.