A Long Distance Run: Interview with Rafal Milach

Rafal Milach (1978) is a Polish visual artist, an associate member of Magnum Photos, working mainly with photography. His work concentrates on the subjects of history and transformation, particularly within the former Soviet bloc. Milach’s work has been shown in many exhibitions. The First March of Gentlemen was an inaugural exhibition of a new gallery for contemporary photography in Riga – ISSP. Milach has received many awards and almost all of his projects have ended up in a book format. However, over the last couple of years he has changed his position from an observer and analyst to being socially and political active, clearly stating his opinion about Polish politics, the increase of discrimination and social inequality. When the strikes were organised to protest against the new abortion law, Milach took his camera and joined the crowds. His experience resulted in a platform Archive of Public Protests, which combines the photographs of the protests that he and his likeminded collaborators had taken. Soon it was followed by Strike Newspaper. During our conversation, Milach often uses the word ‘value’ and redefines what a personal project is.

Photographing the protests, you are the closest to photojournalism than you have ever been.

It’s very strange, I have never worked like that. I don’t feel like a photojournalist. Yes, I use a certain visual photojournalistic frame because I find it the most relevant language when it comes to documenting these socio-political tensions that I have been involved in for the past five years, however, there is a major difference between photojournalism and what I do – I am not trying to objectify the reality. The platform Archive of Public Protests (APP) that I initiated last year, is made by a group of activists, photographers, artists, sociologists who have been documenting the protests outside the institutional or editorial circulation of images. We are personally involved in the process. I believe that the communities I am advocating for are discriminated in relation to the state’s power. They always lose because the imbalance of power between them is immense. I feel like I have to support the weaker and not give a voice to certain systematic mechanisms.

In this context, it’s interesting that your image from the protests where a policeman has pushed a protester to the ground was published with a twisted caption, saying that the protesters are violent, in a way, making you part of the fake news discourse.

That is also one of the reasons why I think that objectivity is a myth. The images are circulating, they are put against a certain background, within a certain context that I don’t control entirely. There is no neutral space in the media. Being on the assignment, being part of the neoliberal circulation of images, keeping the observer’s status in this particular time – everything depends on the context! And the context of today is so divisive and aggressive that standing by and observing is a luxury we cannot afford. Therefore, it’s crucial to be in charge of building the narrative and knowing where your pictures are used. Unfortunately, it’s not always the case – pictures being online, we cannot fully control the circulation and they can be used both legally and illegally. In case of the latter, like my picture that you described, used by the national TV channel – a major propaganda station for the right-wing government – legal action will follow. We discuss the police’s brutality these days. This particular image of the protester pushed to the ground by the police officer – it was the aggression directed towards the LGBTQ communities that were protesting that day. It gives a lesson that you cannot control the message, it is spread on both sides and it can be misused, like deepfakes, fake news and nationwide manipulations, as in case of elections. But that brings us to the point where we believe that an image has the power. Strange realization for me because a couple of years ago I was questioning how much photography can reflect this, the so-called reality. And I have to say, it is still very persuasive but it’s on us how we use it.

How did you become socially active? Was it through photography?

Since I started doing photography, I have been interested in social and transition issues and their consequences. Photography made me reassess in terms of what I am surrounded by and interact with in a humane, artistic and critical way. I understood that photography could be a tool for persuasion and manifestation of my care through building critical statement. You criticize when you care. If you don’t care, you just stand by, you’re not engaged nor involved. I don’t consider myself an activist, I don’t do it on a daily basis. I am a photographer, an artist and sometimes I use my photography and other visual strategies to contribute to the activist sphere. I don’t have the strength in myself to have it as my primary occupation, to be in the field and fight for these important values but I highly respect people who do that on our behalf. It’s a very demanding but also rewarding occupation. My interest in the intersection between politics and art was informed by the context that was growing and changing in the region and my fascination of control mechanisms and propaganda in different regimes – Belarus, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Poland, Hungary – for the last ten years. But for the last five years this started to happen more intensely in my own backyard, so it pushed me to engage more. Since I felt I had some tools how to respond, I picked it up. I decided I won’t be just observing, I wanted to intervene, so the APP platform was created.

You worked in many countries before turning to Poland. Did not Poland have any significant issues that you were interested in at the time? Why is it hard to look at your own country? What has changed?

For many years, my photography work in Poland has been linked to assignments and it was hard to find a space for personal projects at my own backyard. I did the independent work in Poland but I’ve been dedicating most of my energy to the countries declared as corrupted democracies or hybrid regimes. Poland was not fitting that scale at the time but since 2015, when the right-wing populists took over, the power situation has dramatically changed and I was forced to react and focus more on what’s going on around me.

Can you help people in a meaningful way through art?

Yes, I believe so but it has to be done in certain circumstances, because we have to understand that art or photography alone will probably not change or will not improve the world. It will not change our reality in a global sense. But since we understand that we are not alone here, that our actions are a part of certain constellation, of a certain puzzle, that art, activism, and institutional actions, political decisions, altogether they can initiate certain process of change and make this place a better place, and photography can play a significant role in it. Of course, I’m aware how limited it is as an isolated action. But contributing to the discourse with the tools we have, I think this is just our duty to do as artists, as photographers or as engaged citizens. Especially, in these dark divisive times it is so easy to manipulate us as a society. I romantically believe that we can contribute to the change and I actually have some examples where my pictures made the environment a slightly better place.

Can you tell about them?

These situations actually brought back my faith in photography in terms of its agency, cases where photography played an important role in the process of change. There were BLM protests in Warsaw and I photographed a 10 year old Afro Polish activist Bianka Nwolisa with a banner “Stop calling me Murzyn” which translates as “Stop calling me a Negro”. This picture went viral and initiated a nationwide discussion about racism in Polish language. It was after George Floyd’s death, so the environment for the discussion was relevant but it also revealed that, despite the fact that Poland is extremely homogenous, we are a white society without any major ethnic minorities. We don’t think that racism is a problem but it turned out, we had a problem in language. A word that wasn’t considered a problem by the white population has an exclusively negative connotation to those concerned. Eventually, it led to an official statement from the Polish Language Committee to declare this word as offensive. That was uplifting. It wasn’t for the picture but the joint actions of anti-discrimination organizations and activists of the Black Polish communities. We imposed real effects! People who were involved in this action got a huge amount of hate. It was not an easy fight but one small step was made! Even though we cannot erase this word from Polish dictionary, at least we have an official declaration that this is offensive. I think this was an amazing experience of how photography can contribute to certain changes. Also, the image we talked about earlier provoked a discussion about police brutality at the protests. This intervention was totally disproportional to the protesters’ behaviour. There was another picture that that I took on Greenpeace Poland assignment. It was about the CO2 emissions push that Poland and I think two other countries blocked. I took a photo in the power plant, where we beamed the portrait of our Prime Minister with a slogan “shame” on his head. It was a visually spectacular action, it was designed by the Greenpeace activists. This image, too, went viral and it is still widely discussed when it comes to the climate change discussion in Poland. That is input that photography can make in real life. It was also the first time in my life that my pictures were circulated outside of my photography or art bubble, and that was really rewarding. I don’t consider these pictures exceptionally great in a visual sense but what they communicate is strong, and it’s also manifested in a very simple way. Therefore, this notion of photojournalism is relatively easily decodable by people that are not involved in art or photography. So my faith in photography’s agency, as a supporting role within a bigger picture, was restored.

How would you describe the present situation and atmosphere in Poland? Are there still protests happening?

Poland is ruled by the right wing party in combination with Catholic fundamentalists that are influencing Polish politics a lot. Poland had introduced this new, more restrictive, abortion law that was just declared official. It provoked an incredible wave of protests and also started this very formative experience for our society because a lot of things have been revalued, like the position of the Catholic church that was always super formative for us as a nation. And now its position is being questioned. This entire situation was kind of counterproductive for the right wing government and the conservative Catholic communities, because it actually activated the part of society that stands against these radical values. I don’t remember the exact numbers, but the support for illegal abortion has significantly increased. Even if the protests are increasingly weaker because you cannot protest endlessly. The protests lasted for four months. The winter time is also quite demanding to be in the streets. People have been protesting, and the Women’s Strike (Straik Kobiet) feminist movement, which is the core of the protests, is still fighting and proposing certain bills to be introduced, etc. There is, of course, this activist exhaustion, that you experience after being on the high speed mode and high alert. As a person, as a human being, you just can’t bear it for a long time.

Exactly, at the end, we often give up or accept the decisions made for us.

But it is changing! We have to remember that it is like a long distance run. Even if it does not bring immediate political changes, the young generation, today’s teenagers, will be voting in three, four years from now. Hopefully, this political establishment will be able to provide them the space that they can identify with. It is important to manifest your disagreement and to stand up for the values you believe in. Regardless what kind of consequences it brings and what kind of change it can initiate, in what time perspective, this change will eventually happen. I think this is just crucial. I think about constellation again – when the protests go down, certain coalitions and supportive actions are made, other communities take over and the fire keeps burning. This is where I see the role of art and photography. It will perform in a longer term as well, it can be reactive, it can be immediate. It can support the protest movements while they are happening but it also gives us a possibility to do something when the protests are down or weaker, when the protest energy is going down. When you think about the protests in Belarus, for instance, after the first few very aggressive days involving deaths and beatings, police and military brutality, the Belarusian women took over. They kind of managed to take this burden for a few days to keep the revolution going. After that the strength was restored and regained, and the protests were growing and growing all over summer and the fall. We’re not standing on one leg. If we do, it’s very easy to collapse us. We have to have as many legs as possible for it to be more difficult to collapse our values.

What have these protests revealed about the Polish society?

So many different things. First of all, the protests showed that, we as society can be active and engaged, which I didn’t think we could. Also, the protests were not only taking place in big cities. They have been happening and are still happening all over Poland – in smaller cities, even in villages. The young generation joined at such a large scale. That was pretty uplifting as well. They showed that we can unify and fight for our freedom and future, human and reproduction rights. At some point it has become not only about abortion, but about discrimination, about the inclusion and certain economic values, about the social health for people with disabilities. It has become a common fight. That is amazing. This patriarchal system is so wrong. Whenever we see the women in charge in politics, they can create much more sensitive, friendly, open, inclusive environment than this outdated, patriarchal system that we live in. I think it will produce some positive consequences in the future. Also, one of the most surprising things that happened was undermining the position of the Catholic Church in Poland. And we never criticize the Catholic Church in Poland! It’s not about the religion, it’s about the institution because it is corrupted and involved in politics and is obsessed with power. This is wrong but it is also very difficult for us as a society to question our traditional values.

Tell us more about the Archive of Public Protests! How did the idea come to be?

Well, that was quite spontaneous. The contemporary Polish context forced certain actions and one of those was the intensification of the protests since the right wing government took over the power and started to violate the constitution, judiciary system, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights. I started to participate in these protests primarily as a citizen and secondly, as a photographer, taking the camera with me to document. I felt that something formative was going on, and this was the important moment in Polish history. I’ve met people that were in a similar position as I was, meaning, professional photographers not being there on institutional or editorial assignment, but being there as citizens and documenting the protests. I felt it would be good to create a platform that gathers all this visual reality linked to the protest culture. And therefore, it could be a source for researchers, academics, artists, activists. The aim was not to create an agency that would support the images of protests to mainstream media or media overall, but rather to create a source that could inspire other disciplines, to inspire different fields that could prolong the life of these images. That’s how it started in 2019. There was negotiation of the status of this photography – what kind of photography is it? Is it activism, is it photojournalism? Is it our artistic expression? We are still negotiating that but the frame becomes clearer with time. At first, a spontaneous initiative has become a growing structure. Since these protests have become an important part of our daily lives, building this visual representation is extremely crucial in terms of supporting the values that are represented by the protesters. We are 16 photographers and a writer-activist. We all use photography in a way that somehow intersects with different disciplines that we come from. We also have created a quite interesting theoretical database that explains our mission. Karolina Gembara and Paweł Starzec are the ones who are dealing with this theoretical part, writing essays about what the Archive of Public Protests is, along with other people who write critical texts about the APP’s activities. That part is especially important for me because it puts us in a context, and it clarifies the frame that we operate within.

You also publish a strike newspaper. What is the audience of this newspaper and how do you distribute it?

It was also a spontaneous reaction to the Women’s Strike protests as we were thinking how we could possibly enforce this movement with visuals, so we thought that the newspaper can be a banner, a protesting image that is distributed for free at the protests because it is using the same slogans that the protesters are. This newspaper kind of came back to the people that are in the pictures, that we documented. It is an amazing experience to leave your photography, photo book, publication bubble. We created an object that can be an object of protest, that protesters actually use themselves! But since our audiences also belong to art and photography, people treated it as an object of contemplation, which was not our intention. As we saw it, it should have be an object of intervention, primarily. There are great images, beautiful design, strong and useful design. It creates a beautiful object but it’s an object that has to advocate for the values. The protests are extremely visual. We have a lot of tools to create strong imagery that could be spread, become viral and communicate the values that the protesters bring to the streets.

How is the right wing politics manifested in art? Have you received any reaction to what you do from them?

The APP builds, primarily, a critical statement about our government’s actions and decisions. We also cover the right wing protests but we don’t give them the platform. We document these protests as well but the images are hidden in our database. Such ideology should not exist in the public space. The APP builds a statement. It’s been noticed by the politicians. We managed to get the City Hall grant and you have to understand that that bigger cities are ruled by the opposition. There is this clash between the federal government and local governments. Warsaw’s government, for instance, is very much against our government. With the funding we got to redesign our website, I’m quite happy how it looks, and building a totally new interface to make this communication stronger. The local politicians who are on the side of the government were questioning this decision. They tried to block it. There was a little bit of mess and fuss around it. Eventually, they didn’t manage to cancel this grant and, luckily, we could proceed. And another thing – some state art institutions and organizations, like, the Polish Institute, Adam Mickiewicz Institute, these used to be great, progressive institutions that were promoting contemporary Polish art abroad. However, since the change of the government, many of these institutions have been politicized, so I don’t get any support from these institutions anymore. Those are the consequences – if you go out for the protests, you have to be ready to be caught, beaten or sprayed by the police. Major art institutions for many years have been anti-governmental. Recently, the Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, one of the most amazing art institutions we have in Poland has been taken over by the right wing curators. It is demolishing its reputation. There have been some right wing responses in terms of art exhibitions, censorship cases. People that were seen as inconvenient by the authorities have been fired. The art that we can see in major institutions is still independent from political interventions. However, it’s a tricky position for art institutions that are funded by the federal money. It’s kind of a juggling game that they have because they want to survive. Polish theatres, for instance, were always in the avant-garde, they always made the most critical statements about politics or social issues. They are suffering serious problems – it’s extremely hard for them to function without external funding. But there has been good art made as a response to state oppression.

You have been very busy. Have you also been working on another personal project?

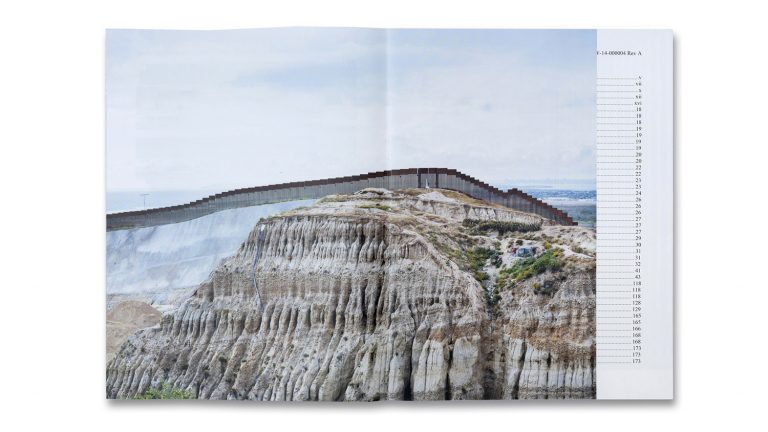

Well, this is highly personal, like none of my projects have been, I have to say. I have never been involved with such a personal engagement, because it’s happening in my own backyard, it’s against the values that I stand for. The struggle is on in so many fields. The year of 2020 was probably one of the most difficult years for our society. It was also one of the most hard working and exhausting but also inspiring years in my entire career – in terms re-evaluating my understanding of what I am doing. That was fundamental and just great. In the meantime, I am working on different projects. I’m about to release a photography book I’m Warning You. It has been postponed for six months already. It’s about propaganda, about the anti-immigration issues and divisive political environment. The border walls are the emanation of it, they are the monuments of propaganda. I hope to release this book because the problematics of it is very important, and it’s very much related to our struggles today – the migration crisis, the nationalistic propaganda. It’s not that I don’t care about what is going on elsewhere in the world, but right now my direct surrounding is so messed up that I feel I really have to commit mostly to that.

What drives you in life? What drives you to make art?

The answer is pretty simple – I like to interact with what surrounds me. I like to observe, I like to meet people whom I would never meet otherwise. It maybe sounds banal but art makes me engaging and reactive. Everything from expressing my feelings to building critical statements, putting myself or being in situations that I wouldn’t otherwise confront. Photography pushes me to build a position.