Giving thanks to the past. Interview with Zane Onckule and Sophie Thun

Contemporary art centre kim? just opened a unique show I Don’t Remember a Thing: Entering the Elusive Estate of ZDZ that exposes the neglected artwork of Latvian photographic artist Zenta Dzividzinska (1944–2011) and Vienna-based artist Sophie Thun (b. 1985) who pays her tribute to the artist and the previous generations of women artists by working as a technician and printing Dzividzinska’s previously not reproduced works. One of the rooms in the exhibition space has been transformed into a laboratory where, with the help of archivist Līga Goldberga, Thun will be printing for two months and constantly adding pieces to the exhibition. Even if in the 1960s Zenta Dzividzinska was one of a few women photographers in Riga with significant work about women as well such as House Near the River, overall Dzividzinska’s work was considered too experimental and unconventional for her time, something that Thun doesn’t have to explain or justify. Thun is interested in the photographic medium and how she, with her image, is contributing to it. Her work has a lot of reference to painting, which was her first form of artistic expression. The curator Zane Onckule remembers meeting Zenta Dzividzinska at photography magazine Foto Kvartāls, the one that predated and gave the title for the current website FK where Onckule was photo news editor and author of texts but Dzividzinska was the creator of magazine’s design. In terms of her actual art, the first Dzividzinska’s exhibition that Onckule saw – I Don’t Remember a Thing at Latvian Artists Union gallery in 2005 – also left a big impact on her understanding of how one can make exhibitions, how one can install and how the display could be organized.

How did the idea to invite Sophie Thun and make this specific configuration come along?

Zane Onckule: As a curator, I have several parallel ideas or streams of thinking and I like to take it slow with such kind of exhibitions, so it doesn’t feel rushed. I would say it has been almost a decade since we had this idea in mind. Alise Tīfentāle (Zenta Dzividzinska’s daughter) was telling me about the condition this archive was in but then I went to study to the US and the archive was stored in one place and then another. When the pandemic started, we were both here and we understood that maybe that was finally the right moment. I knew from early on that I really wanted to have a dialogue or maybe a conversation with a living artist and it was clear that the person should be a female photographer or a person who identifies as one. But I had no idea in what way it would happen. An immediate idea was to approach a young Latvian artist but nobody resonated with the ideas that I had and how I saw Zenta’s works. I remember vividly that last spring, during the pandemic, I was reading these nonstop e-flux announcements. Some of them you read, some you just delete. I don’t know what exactly caught my attention but I saw this announcement of Sophie Thun’s exhibition at the Vienna Secession, major establishment. I think, one of the oldest artists runs the space that was founded in the late 19th century. The text read that Sophie has brought her darkroom into one of the exhibition spaces where she was working undisturbed on ongoing projects and making the works in this laboratory for about two months. Understanding Sophie’s work and the way how she uses analogue techniques and how she incorporates the female body, like her own image, I immediately saw similarities. I was curious if Sophie would find Zenta’s work interesting. And the reaction was immediately positive. What we see now at kim? was actually Sophie’s idea; she wanted to be here for two months and work in the darkroom.

Could you say that you somehow identify with Zenta Dzividzinska?

Sophie Thun: I do find similarities. In the article written by Alise Tīfentāle there was a sentence about the images where Zenta is depicting these self-sufficient women. I think we have this self-sufficiency and in-betweenness in common that is not so much about proper photography but more about working with a medium. So for me, the darkroom work is the most important aspect, and Zenta had a lot of experiments with solarization, and photograms. It was less about doing technically perfect images, just about what the medium itself is. I think we both try to dissect the medium. When I was reading about her, it was always mentioned that she was one of the few women in this very male photography club environment. And of course, it’s a medium, which is incredibly expensive to produce. I don’t have to support anyone as she did. As far as I understand, she really stopped doing photography and Alise didn’t know until the 1990s that her mother was an artist. I don’t have this situation but I do know this in-betweenness where you have to have jobs and where you are doing artwork on the side of jobs. That’s why for this show, I decided to work as Zenta Dzividzinska’s technician, so I’ll be doing her work for her.

What are the works we see in the exhibition?

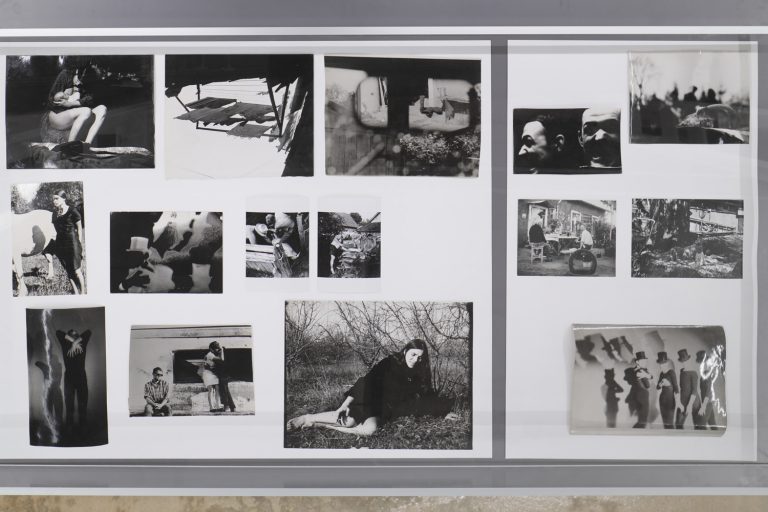

ZO: We have Sophie’s works from private collectors in Vienna and Zenta’s works from the National Museum of Art collection. We knew that we wanted to highlight different hierarchies. We turned one of the exhibition spaces into a laboratory with approximately 15 boxes of Zenta’s archives. Within these boxes, there are negatives and prints that have been in there for 15 or more years. And then we have an elevated section of the exhibition where we have properly framed prints from both artists. Those are the hierarchies of visibility. The exhibition is a growing organism since Sophie will add prints from the negatives that she will find in these boxes, with the help of archivist Līga Goldberga from the National Library. So she will sit down and work, box by box, and try to understand what we have. She will also consult or advice Sophie on which material is interesting, which material she should have a look at. Our ambition is also to go through all the material and take further steps in categorizing, helping this archive to survive for the next decade. And the last component are some large scale works that Sophie made while her visit in Riga in April – a photo of kim? space, evoking the idea of trompe l’oeil and also photos from the National Art Museum storage place, and the place where Zenta’s archives were held.

How did you approach making new pieces for this show?

ST: I came in April for four days, I wanted to see the space because I almost always work site specifically. I also wanted to see the archive; we went to the storage facility. I brought my large format camera and took some negatives, because I wanted to incorporate the different places of production along with the different stages of production. Her work from the museum collection is on show. I thought it was important to show the place where these boxes were brought from. And there’s also one piece which shows kim?. That is an enlargement one-to-one size and hung in the place where I shot it. It’s the type of work I first started doing photography with, where I would simultaneously show and cover reality, which I feel photography very often does. Because I’m printing her work, I’m also inscribing myself into it. It opens a lot of questions about who, for example, gets to keep the work or take it home. Where does it stay? I’m very curious about that because I’ve never dealt with that type of work. I work as a technician for other artists, but I refuse to print for other artists. That’s like the only thing I don’t do. I can be their camera operator, I can develop film, but, because for me, my work is primarily printing, that stays for me. So Zenta is the first artist whose work I’m printing. I feel very lucky. It’s a great team here!

What is the role of an institution in preserving and raising awareness of an artist’s heritage?

ZO: We have to take care of younger living artists, or young female artists but at the same time, I think this is an interesting combination. I see this exhibition as a new direction that kim? could incorporate. We have, of course, 10 years legacy of producing and giving space for younger Latvian and foreign artists but this could be a new approach in the future to also revisit the past. As an institution, we work responsibly but we also understand our own limits, because producing this exhibition proved that we didn’t have enough experience; however, we found solutions, for example, by inviting the archivist who will protect and organize or reorganize all the archive. Also, I think we already have shed some light to Zenta’s practice and through the dialogue with Sophie we satellite to international partners already. And then, of course, Alise has done a major work of informing about Zenta’s practice in various conferences.

Why are you working with analogue photography techniques? How did that start?

ST: That’s funny, it’s a very common question that people ask. I used to be a painter. When in painting, no one asks you why you’re using oil and not aquarelle, or not acrylic. It’s somehow perfectly legitimate, that there are more means of expression.

I guess because today it’s almost exclusive to still work in large format analogue photography because it is so expensive and because there are not many labs left in the world.

ST: But in the past too, the enlargers were second-hand and they haven’t really changed that much. Except for colour machines. But my journey started when I was still a painter. I first studied graphics in Krakow, which I also have in common with Zenta. I also did graphic design jobs, less than her. I think she was a much better graphic designer than I was. Then I moved to Vienna to study painting with this German painter Daniel Richter but I had a very hard time working in a class full of people painting and listening to music. I discovered at some point that one floor lower, there’s a darkroom, which was empty, because hardly anyone works analogue. I could just close the door and be alone in this room

and turn the light off. So at first I did only colour because you do colour in complete darkness. When you paint, you make something and I like making things. What was confusing for me with photography at the beginning was that you can work in a way that you just make an image, which can be one second, and then you give away the whole materialization. And for me personally, the materialization process is the most interesting part of photography. I also make collages. I’m not so interested in taking images, I’m more interested in making them. I guess you choose your medium according to how you like to spend your life. Some people like editing, some people like traveling and have small cameras, I like spending hours alone in the dark.

How will you proceed here? Is there an agreement in place?

ST: The first selection comes from Alise Tīfentāle who brought a selection of boxes. None of us really knows what’s in these boxes. Then I’ll be picking out I guess, randomly, until we find a way of organizing them, and printing. We’ll be developing a system with the archivist. It makes sense to keep the archive as safe as possible.

Do you have any expectations from this time, two months working in Riga?

ST: No, I have zero expectations. I feel extremely lucky to be trusted and that I’m allowed to work with this material because a lot of it has never been printed. For me, it’s also wonderful because I’m also a woman working with photography and I have shows and funding. With all of this I can say thanks to the generation of women who never had these opportunities, but did all the groundwork so that I have these opportunities. I thought that for this show, I’d like to at least a little bit, serve Zenta and be her labour. Of course, I’ll be printing differently than she did. The paper, for instance, is no longer used by the industry. It’s a limitation in the analogue photography, so the prices really went up. And there’s less and less types of paper.

But in Dzividzinska’s time, in Latvia, there also wasn’t a big choice, she only printed on the available size.

ST: Of course. What will be different for me in printing is that I have this role. When I used to paint, my first decision was the size. I’d make my canvas first, and then I’d paint. And in photography, you can vary, it’s a medium where you can enlarge. So you can choose the size after shooting the picture. I have this rule for my work that if I enlarge, then I enlarge to the life size, which results, in this case, to a print four by five meters. Or I make contact prints, it’s based on touch, I put the negative on the paper directly. With Zenta’s work, I’ll be enlarging. So it’s something I don’t do for my practice, but that she did for hers. Nevertheless, I’ll be inscribing myself in the work somehow. I’ll find out how during the show.

It’s interesting in what role this project puts you in. The exhibition entitles you as an artist–technician but there is something performative about it as well.

ST: I like this term. The two technicians that were installing the show with me, for example, built these tables. The technicians are a huge but invisible part of art exhibitions. These two wonderful guys who did the show with me, they’re also both artists, both sculptors, which I think is very visible. Therefore, I like this term ‘artist–technician’. As to the performative act, definitely, it’s there. I think my work is quite connected to performance anyhow. Zenta’s work also, this offstage pantomime work, it’s a very specific type of photography she did. It’s amazing how she managed because photography is a very tricky medium, she really managed to make out of focus images or that no one is posing. I love this about her work. But in my case, in terms of the performative aspect, I have a choreography here which is fixed by the medium I’m working with. It dictates my movement. I’ll be basically having this routine, connected to movement for eight hours a day. I won’t be here every day but I want to be here at least four days a week.

The show will be changing through this performance of putting freshly printed images on the boards.

ST: Yes, especially, if I manage to print on a bigger format. Zenta, if I’m not mistaken, only printed on 30×40. Some of the negatives have stains, some have marks of the storage. The passing of time from the moment she took the images to now will also be visible, which is also interesting, for me. It’s like compressing a lot into one piece, that is what interests me in my work. There is a tradition in painting where you would show a whole story in one work, for example, the Garden of Eden, so you have different stages of time compressed. I like this idea. In this work, if I inscribe myself into the prints, it’s at the same time a piece, which was made in 1960 and in 2021. It’s like making a time sandwich.

Can you talk more about the use of self-portrait in your art?

ST: I don’t see them so much as self-portraits. When I want a body in the work, I just use myself because I haven’t found a way in which I could photograph someone else for an art context where it would work for me or because when I use myself, I just use myself as part of the machinery. I’m part of the production process. I have these collages in this show which I started making in hotel rooms while on jobs. I was working as a technician for these artists senior to me, we were producing their artwork. And then after my working hours, in the hotel rooms, I was producing my own artworks. It was a play with hierarchies, this co-dependency – they need my technical skills to make their artwork and I need their money to buy my materials to make my artwork. I couldn’t make art without them and they couldn’t make artwork without me. Whereas in my case, I use myself because I’m available 24/7, I have very strange working hours. Some of those pieces were shot in four o’clock in the morning, so, I guess, it’s also a practicality issue and in a way, an ethical decision. I started with the self-portrait because I was interested in showing the specificity of medium. There is this genre in painting where painters show themselves paint. One of the most famous is Las Meninas by Velasquez. There are fantastic self-portraits by Artemisia Gentileschi and Sofonisba Anguissola, where they are at the easel painting. It’s also a genre thing and it’s a showdown with yourself, because at the same time you’re shooting, but you’re also being shot at the same time. So it’s possessing, but also being possessed. I was also playing with this a bit in these collages. Zenta somehow managed to photograph others in a way that totally works out. These women, in her photographs, they just seem so incredibly at ease, as if they don’t care about anything. I’m very excited to see these photographs from the House Near the River series.

What are the difficulties of being a woman artist? What do you think has changed, for example, since the time when Zenta was working, and what still remains nowadays?

ST: I think it has really changed in the last couple of years. When I was studying, there were still hardly any female artists in galleries. There weren’t many solo shows, and there weren’t many non-male artists represented by the galleries. That has really changed in the past, maybe, five years. I think it’s not only about female artists. I think it’s about everyone who isn’t necessarily a white guy. The art world has to catch up with reality. In general, it’s a moment of huge change right now. But for me, it’s definitely easier than for Zenta Dzividzinska. I live in Vienna, which is a city where there’s funding. Economically, it’s much easier. The times are very different also. Unlike her, I have incredibly many privileges. Pay isn’t the same for female artists and photography in general is not so easy. It’s a niche in itself. Not enough has changed. If there is a child, a woman is immediately considered the main caretaker whereas a man can continue the artistic career. Zenta was really incredibly tough. Everything I hear about her is quite impressive.

Do you hope that this exhibition will bring the necessary recognition to Dzividzinska’s work?

ZO: Yes but I am also a bit critical towards the practice where an institution, for instance, finds something important, cleans the dust and then presents it as something historical and include that in their sales. I think there are ethical problems to that. Nevertheless, I really have confidence in Zenta’s works.

Will kim? stay involved in Dzividzinska’s archives, new printed works and future activities?

ZO: This is a really interesting question and I’m sure I should have a clearer answer. For instance, we are about to speak with Sophie and her gallery. It’s clear for the new prints, Sophie can sign them as a printer for the future archive or collection whoever would like to acquire these freshly printed works by a known photographer herself. But then there is also the question what happens if Sophie decides to use an image for her work? We have a permission from Alise that Sophie can play around, like include the hands in her works but who owns the work or the right of authorship? Will the work be unique or editioned? These are the questions we have talked about and are dealing step by step.