Unveiling the realness. Interview with Max Sher

Max Sher (1975) is a Berlin based Russian art photographer who is interested in cultural and political issues, raising awareness about the power of photography through showing the everyday and the built environment that usually do not make the covers of print media as opposed to over-used clichés. His projects are usually long-term explorations about the post-Soviet space and through the projects he expresses personal commentaries on the system. Sher’s work has been exhibited as part of solo and group shows both locally and internationally, including the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the Moscow Museum of Architecture, the Triumph Gallery, the Format Festival, and Noorderlicht. Sher is the author of a number of artist books and zines, including Palimpsests (2018) and Infrastructures, a joint photo book with Sergey Novikov published in 2019.

When and why did you realize that photography is something you want to do?

It was a certain accident. My father used photography a lot for his work, he was an archaeologist and needed to record. He also taught it at Soviet leisure center “The House of Pioneers”. He was very involved and had a lot of gear and magazines. But I, for some reason, wasn’t interested. My interest in photography grew by itself when I was already 25. I was working as an interpreter at an American owned paper mill, on the Russian-Finnish border. It was a very boring place, so what initially pushed me to photography was just a need to pass the time. And then, step by step, I realized that it’s something that I want to pursue as a profession. I got to know photographers in St. Petersburg and started to attend various masterclasses and different photography related events but it wasn’t until 2006 that I actually did my first story for a magazine.

You also have an interesting background – you grew up in Siberia.

Yes, I’m a sort of “Wandering Jew”. I was born in St. Petersburg, then at the age of 11, after my mother died, my father moved to Siberia because he got a job there as a University professor. It was in 1986 when Gorbachev came to power, he wanted to boost education in the remote regions. We moved to Kemerovo which is like a hellhole in a way but it became my second home. I lived there until the age of 23 when I graduated from the university and then went back to St. Petersburg, lived there for another 15 years, I guess, and then moved to Moscow in 2011. And now, after 10 years, I’m in Berlin.

What kind of mindset or what ideas do you think you obtained living in such a remote place as a teenager and a young adult?

It actually wasn’t the most remote place, neither the wildest. Siberia is quite diverse, as Russia itself. It’s fascinating, it was so interesting in terms of exploring its history, its geography, its everyday and especially in my case, its representations, how Russian people, not even foreigners, actually perceive that space. There are tensions between how people see various places, between those who live in Moscow, and those who live outside Moscow, even between Moscow and St. Petersburg there are huge differences. And needless to say, between Moscow and the regions. Russia is still an empire with an imperial government model. It’s a very archaic and colonial relationship which is not recognized by people who govern. At the same time, it’s an interesting topic for artistic research and for me specifically because I grew up far away from where I was born, and from where I lived thereafter. I saw how such places are being thought of, in Moscow and beyond, and especially outside of Russia. That is one of the reasons why I worked out this approach that I used in my biggest project Palimpsests.

What is this approach?

This approach implies that the photographer has to focus on, pay attention to, and record landscapes and infrastructures from the point of view of the local, from the perspective of the local experience and cultural references, thinking less of how it is going to please the ‘market’.

What brought you to your interest in the post-Soviet thematic? How political are you within this topic?

The political aspects of my work are not overly manifested, they are hidden in some corners of the pictures, but the way I look at the topic is political. When I started out as a photographer, I began to see how different photographers capture the place where I live and realized that it’s changing very slowly. Exoticizing the approach to it is like othering, even a little arrogant. And that is the main tension of this project – to de-exoticize it, to represent it from the point of view of the everyday, and to get rid of any exotic clichés. It is a dangerous path. When you begin to fight this Western exoticizing approach you stand on the same platform as Putin’s government in some ways. But I take responsibility for it, because, on the one hand, it’s what gives me some kind of independence, preserving my own perception and my own vision. And on the other hand, not being associated with any political movement, if I might say so. These great power politics notwithstanding, these tensions do exist, and one cannot avoid talking about them. And especially when photographers who work for the Western media are expected to take certain images, who keep reproducing these clichés.

Can you explain what is the image that Western media expect?

They are images which reproduce all the same things – a bear, an orthodox church, a nicely looking young girl. All these things exist but I don’t see the purpose of showing these clichés when there are so many other things. It feels like they are treating the readership as idiots.

The angle you have chosen to show is also just one point of view.

Definitely. When I was a kid, I traveled a lot to many remote places. And then roaming around alone, and taking pictures is also part of the story, because you can’t concentrate if you go with someone, you need to be alone to sharpen your vision and to observe closely. From the artistic and political point of view, it is one sided approach, I do recognize it. I chose it on purpose to try to focus on and represent the built environment. I was 16 when the Soviet Union collapsed but I still absorbed some of the Soviet imagery that practically excluded the everyday imagery and the built environment was only featured on the postcards, and they were at a very specific angle. So my purpose at the beginning was to find a middle way between the exotic and the Soviet ‘sublime’ where the imagery was a feel good approach, showing our cities growing fast and industries developing, and people celebrating, and so on. But the built environment as a subject matter didn’t exist. I attempted to bring this subject matter back into the art photography without whitewashing it, showing it with all its shortcomings and ugliness. Up until the early 1930s when the doctrine of Socialist Realism was forcibly introduced as the official Soviet art ideology, meaning the reality would have to be portrayed as it should be from the party perspective, and not as it was, every small town in Russia had a photographer who was recording the built environment in the same way as anywhere in the world. One of the most pleasant moments was during a show in Yekaterinburg when people who came to the opening day, said they recognized their habitat in the images, they experienced joy of recognition, a feeling that moves people.

You said that a lot of places that you photographed, were photographed for the first time, since they were not allowed to be photographed during Soviet times. Have you ever encountered a situation that one of your photographs is still a problem that it was taken? How is censorship manifested in Russia today?

When I was working on this project between 2010 and 2017, I hadn’t encountered any problem except for one instance when I was photographing under a bridge and I was yelled at by a security guard from above that it was not allowed because it was what they call the ‘strategic facilities’. But now the political climate is changing very fast, it’s becoming difficult. Photographing is still okay but the situation might deteriorate very quickly soon, like it was in Belarus. Even before the latest protests it was a very hard dictatorship and it was not allowed to photograph government buildings. In Russia, there was no problem with it. Now, they are strengthening the rules on all fronts. Photography is not in the spotlight but I guess it will suffer at some point. People are starting to be frightened to talk to the media, especially to the foreign media, and many Russian media have been closed or labeled as ‘foreign agents’. This is one of the reasons why I left. There is a new, so called, law on foreign agents saying I had to go to the Ministry of Justice and register as a foreign agent because most of my income comes from abroad. There are two conditions – you receive money from abroad and you are involved in politics, and involved in politics can mean anything, even if you have commented on some blog on a political topic, that is making you a foreign agent. The whole process is totally Kafkaesque. But if you’re a foreign agent, you are obliged to register and to report all of your expenses, like buying milk, you have to make reports and send it to the Ministry of Justice.

That sounds crazy! Is it safe for you to go back to Russia since you didn’t register as a foreign agent and left?

Most probably it is safe for me personally, because this ‘law’ is not a law, that is something that fairly regulates some social interaction or exercising a right, but a tool, an arbitrary unlawful ‘crack-head’ at the hands of the security apparatus designed to intimidate independent media, and more specifically, its most vocal outlets overtly opposing and denouncing the regime’s corruption and crimes. I am not an investigative journalist but an artist but if someone, for example, reads this interview and discovers I knew I had to register and did not do it, they can turn me in to the relevant ‘authority’, then of course they can label me as a ‘foreign agent’ as well, and easily so. That’s the principle of mafia state: the rule of uncertainty and no rule of law. Everyone should be scared and keep one’s mouth shut. There is a public outcry regarding this ‘law’, not that strong unfortunately because people are scared, but still, and they say they might amend it to make it more like a ‘law’, make the security thugs go through a court at least to allow the potential ‘foreign agents’ to defend themselves. Nobody knows. But our mafia tsar wants this law to be there, that’s his vision of the world.

How did the idea to collaborate for Infrastructures come along? Have you worked with Sergey Novikov before? What was each other’s role and working together like?

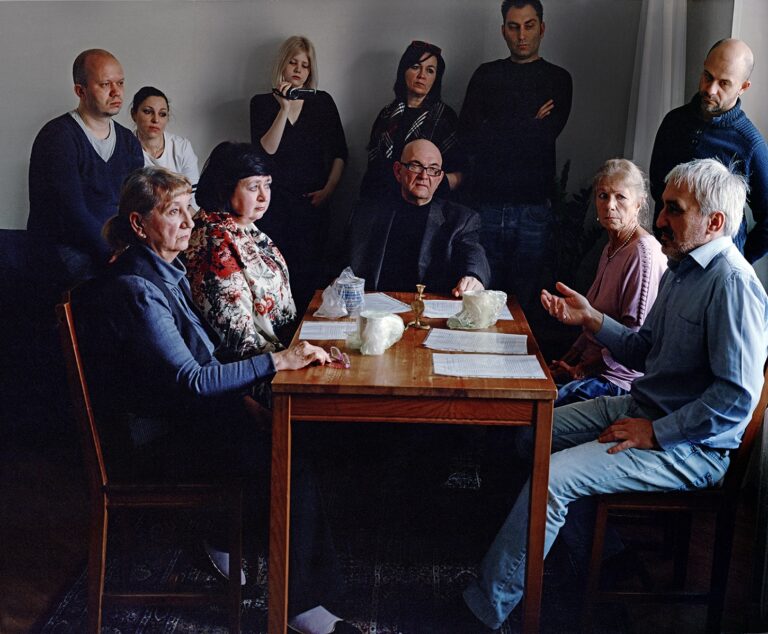

We have been friends for quite some time, he suggested we could do something together and we made sort of encyclopedia of how things work, both of us agreeing that the manner how post-Soviet context is being represented in photography does not satisfy us. We wanted to make the photographic discourse about the post-Soviet environment more complex, more diverse, more layered and to also find some similarities with other political regimes since we live in a dictatorship. We wanted to focus on the political economy more than on the journalistic aspects of photography, not showing poor people but showing the structures of power. My approach was more documentary, his approach was staged photography. For the latter, I was assisting him but we were constructing the scenes together.

Are you the authors of the essays as well?

Yes, we wrote them ourselves.

I didn’t notice that you would caption the photographs or sign the essays. Is it such a collaboration that you don’t even say who is the author of each photograph and text?

We presented this as our collective work. In some instances, I assisted him because he, for example, knows how to use the view camera and I don’t, in other cases, I went somewhere on my own and in other cases yet he went somewhere on his own and sometimes we went out together just to take one picture but we were together because we needed to select the right angle. We were in a way inspired by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, you can’t tell one from another with their image. Looking back at this body of work now, it fascinates me that we were able to make this body of work in just three years.

What were the main discoveries and conclusions after such a huge work that resulted in a 360 page book? What would you like people to take away from this edition?

We weren’t satisfied how simplistic the photographic discourse about the post-Soviet environment was. Our approach was to show or to make people see that it’s far more than those clichés, we wanted to get rid of the fairytale and the absurdity aspects of it. Our purpose was to be sort of cultural critics. At the beginning, we didn’t want to include so much text, but then we realized that in order for the work to be something to be reckoned with, we needed to go deeper into the subjects that we were tackling.

What feedback did you receive?

In Russia, inside the photographic circle, it was quite well received, it was really something that wasn’t attempted before. We were lucky to receive funding from the Heinrich Böll Foundation. On the other hand, the feedback outside wasn’t really satisfying. We have sent it to many contests and festivals, and it did participate in some but otherwise, for some reason, there was basically silence. I’m not sure if it’s worth saying it, but we were expecting something more because we put a lot of effort into it conceptually. The process of doing it was fascinating and we recall it with a lot of good feelings like when we were traveling, taking pictures and talking to people. Photography is very much dependent on light and when we had to report to our sponsor why we spend more money on air tickets, we had to explain that we had to be in that particular place at a very particular time because if we arrived an hour later then the sun would be shining right into the camera and the image that we were looking for would be completely spoiled. It’s such a huge country, we had intricate logistics and had to always keep in mind how we will be traveling between point A and point B. The project was a great adventure in itself. Once we actually were late for our plane back to Moscow because, in the area where we were there was basically one road that connected the city with the airport and that road was blocked because of heavy wind and snow. So the taxi driver had to make a huge detour. At the same time, we called the airport to ask them to wait for us. And actually it worked.

What are your plans now that you have moved to Berlin?

I have a lot of ideas that I want to work on but I will be able to travel only when I receive my permanent residency. A project that is now underway is a book about a specific aspect of Soviet architecture which has not been properly explored, about small houses that the Soviet Union built all over the country right after the war, from 1945 to 1950. Every city, every town has such two and three storey houses, which were the first truly mass-built housing projects in the Soviet Union. In the 1920s, there were some experiments with housing projects but there were not many. Most housing built in the 1930s was intended for the ruling class. The demand for housing was huge, but it wasn’t met because Stalin put all their efforts into building factories and building the army. People were struggling in the communal old houses or even in the dug-out bunkers. So the first mass housing project was not the five storey buildings built en masse under the Soviet leader Khrushchev (and known as Khrushchyovki) but those small houses and for some reason this topic was never explored by Soviet or any other historians of architecture, maybe they are not of a big artistic value but they have a big social value for people who lived there and grew up there. I thought that it needed attention because many of them have already now been demolished to make way to high rises. And part of the story is very personal – my maternal grandparents lived in such a place where I also spent a lot of time when I was a kid in Leningrad. That particular area has been under a threat of demolition for some time now. I suggested it to a journalist friend, Yulia Galkina, to write something about this phenomenon, and I am happy she quickly agreed. I have already photographed 60 houses that are part of my former neighborhood. I hope the book will be out in about a year, we were lucky, because we immediately found the publisher in Moscow. The project is not really an art project per se, I mean, it’s still photography but maybe a bit different, let’s say, it’s my way of doing things. I’m at times working on the margins, or between different fields. Like in this case, it’s basically working with a journalist on a book, which is not specifically an art project in the context of contemporary art, but it is for me a creative work and on the topic that I consider interesting for myself, as well as from the point of view of art history. Why it wasn’t addressed before is because this area was mostly built for the working class and is still populated mostly by the working class. My class consciousness suggests to me that the reason why it wasn’t included in the history of Soviet Architecture is because most art historians come from a different class, they are not interested in it, it’s not their life, but it is mine. I’m from a working class, my parents were the first in their families who received higher education, before them, all of my family members were workers or craftsmen. There is something personal and there are class-related reasons here, which I want to write about in the preface of this book. The Russian approach to the history of Soviet and Russian architecture rather focuses on the styles, star architects and their biographies but very seldom on the social, political and everyday aspects of it. Yulia Galkina is making interviews with people who used to live there, who still live there, about their experiences, not about the architects who built this specific neighborhood even if those who built this neighborhood were actually quite well known architects, and one of them even became the chief architect of Leningrad after he built this area. Another interesting aspect of it, this kind of houses actually are called German houses in Russia, because part of these projects were built by German prisoners after the war. There is still no official evidence of how or where (on which sites) they worked. Yulia actually went to the archives and these materials are still secret, they are not declassified yet. German POWs were kept in captivity up until 1950. Going back to your question, I will also have one gallery and one museum commission next fall, one in Moscow and one in Tula, which is a military industrial complex city, about 300 kilometers south from Moscow. I suggested to them to make a set of postcards, but put some everyday built environment, not the touristic sites, on them. They were very interested in producing it. I will need to go there and photograph in the way that I used to photograph for my project. And another one is similar with the Moscow gallery. On a personal note, I will probably have to reinvent myself, I feel very strongly that while you are here in Europe, you have to either remain in that sort of a ghetto for the Eastern European photography and continue to produce some exotic imagery, which I don’t want, or you have to become a Western photographer, focused on some things that truly interest Westerners, to become a Westerner. I don’t know how it’s going to play out. That’s an interesting task in its own right.