What do photographs do? Interview with Jörg Colberg

Jörg Colberg’s name is well known for people, who are part of or are interested in what he himself calls photoland – the realm of contemporary photography that often can feel a bit cut off from what is going on in the rest of the world. Colberg is opinionated and sharp, and has attracted a devoted audience through his popular blog Conscientious, which he started in 2002.

Last year Colberg had two books published – Vaterland (Kerber Verlag), a photobook with images from his native Germany, and Photography’s Neoliberal Realism (MACK), a theory book invested in looking into the role of photography in society. Based in in Northampton, USA, Colberg has been teaching photography at various institutions for about ten years, and is now doing the workshop Text and Image, Image and Text with ISSP, currently open for applications – it is going to happen for the third time later this year.

Ieva: You’re a writer, teacher, photographer, and these things seem to feed off each other, and I just wanted to ask you if you want to say anything about that? We could also speak of these things separately – you as a writer, you as a teacher, you as a photographer.

Jörg: It would be crazy if these activities were completely independent, even though in some ways they are a little bit. When I write criticism, I have to shut myself off and do that job. But of course, there is a relationship between me as a photographer, as a writer, and especially as a teacher – I’ve taught photography for 10 years. It would not be right to give people advice and not follow it myself. In general, I try to do things that I tell my students about.

My first photobook was published last year. One of the reasons why I wanted to make a book was that I wanted to go through the process of making a book myself. That way, I would learn all the details that up until then I had only known second-hand.

Ieva: You have also written about photobooks a lot, and didn’t you also do a book about photobooks?

Jörg: I was always interested in books, and I read a lot. After the 2008 financial crisis, I understood something. I used to go to New York to visit galleries. After 2008, I realized that there wasn’t any interesting photography any longer. Instead, galleries were showing pretty stuff to sell. So I stopped going and I started looking at books. The book is a great medium to show and to work with photography. That’s why I’m interested in books and why most of my teaching involves that component.

Ieva: I wanted to ask you about your teaching. Well, firstly, you’ve been teaching a class with ISSP, and it seems like it’s been doing pretty well as you’re doing it for the third time this December. What do you do together with your students? How do you see your role as an educator?

Jörg: Maybe, it’s easier to tell you how I do not see my role. I don’t think telling other people what to do is a good way of teaching in creative environment. I have a background in natural sciences. That approach works in physics, where you can tell people to do things in a certain way and it will work. But in arts, the approach usually is bad. As a teacher, I see my role as someone who helps people make their own discoveries. That means that I might suggest certain things. But I also spend a lot of time with students talking about what pictures do and how they do that, and whether they really do they think they do.

That particular workshop was about image and text, and it was a little bit more experimental. It was designed for photographers who wanted to work with text. In the beginning, I showed them a lot of examples. Then, everybody had to talk about one book of their choice. It is a good exercise to look into the book and try to talk about it – there is no right or wrong anyway. Then, people started working with text by writing their own text for photographs. It was pretty experimental: encouraging people to try something and to then see how it works. Does it do what you want it to do?

A lot of photographers are very shy when it comes to text. People often say, Oh, I’m not a writer. If I wanted to be a writer, I wouldn’t take pictures. I think that’s just a silly excuse, because everybody knows how to write emails, letters, shopping lists, or whatever else. It’s not really that different. Usually most artists find out that writing is a lot easier than they imagined. It can actually be fun, and it allows you to make something with text and image that you cannot make with pictures alone.

Ieva: I think maybe sometimes visual artists struggle with the combination of image and text, because – even though language can also be pretty open ended – sometimes when we put words onto images, they can constrain meaning. That annoys me a lot when I go to museums and there are texts that tell me what I should think about what I’m seeing.

Jörg: One thing that I always tell people is to not see it as a competition; you want to see text and image as partners. You have to think about what you want the text to do. Text can do certain things that pictures cannot do, and the other way around. There are certain things pictures can do, and you cannot really do that with text. Once you start thinking about it like that, it relieves a lot of anxiety about text restricting images. Sometimes, when people get very anxious, I tell them to treat text as if it were an image – just a different form of an image.

But I understand what you’re saying. Of course, in a museum, text has to play a certain role. Text is flexible. You can use it in different ways. In a museum, you can use it specifically to make people think about certain things – to educate them. Whether that’s good or bad is a different question. Plus, as a visitor, you don’t have to read the text or accept it as is.

Ieva: You’ve been in different roles as an arts educator – you’ve worked at a university and also as an independent teacher. I feel like at the moment, there’s a lot of debate about what art education should be like. On the one hand, people complain that they spend a lot of money and time in art school, and then the institution doesn’t give them actual tools to survive as artists in the real world. While other people say that there’s no way you can enter the art field if you don’t have that network, which you can only access through these programs. And then there are also people who do these sort of workshops or artists who teach via platforms like Patreon or Discord. I was just wondering what do you think about all this and where do you see yourself within these structures?

Jörg: That’s a really good question. It’s really complicated. For example, in the United States education is commercialized, even at state universities. It’s basically a business. The reality is that people have to pay a lot of money every year just to go to a MFA program. I grew up in Germany, where I don’t think that system even exists.

When people tell me that they are thinking about doing an MFA, I always ask them, What do you want it for? What do you want to get out of it? Don’t think about the title or the network – as an artist, what do you want to get out of going to a workshop, going to an MFA program, doing mentoring? And then approach it that way.

I think there is some truth to MFA programs providing a network. It does seem like an expensive way to get a network. But if you want to spend $100,000 on getting a network, that’s fine. Networks are important. This is such a career-centred way of thinking about it, though.

A more interesting way to think about it is the following. Find a group of trusted friends that you can talk to about your art, a group that is your network. I think that’s more important than a network that can help you to get into galleries. Again, there are two sides to it. There’s the business side – as an artist, you have to get the word out and people have to see your work. That’s different than people seeing your work and telling you this is working, this is not working, or why don’t you think about this.

Ieva: I agree, but I think that maybe people, especially in the US, do think about the career side of it a lot, also because it is such a big investment. I was talking to an artist, who went to art school in the 1970s in California, and at the time it cost a lot less, but students didn’t really expect that they would ever make money out of their art because it was just not a thing – people going to art school were weirdos, really. And now I think that the art world in this sense has changed. People go into school also with the expectation that they can make it into a career, and it puts it in this kind of impossible bind, because it’s a gamble. But depending also on where you are. I have some friends who are in art school in Germany, and I think you just pay like 300 euros per year, which is also the bus ticket for the year or something like that.

Jörg: It is a gamble. We have to remember that a lot of the people who went to art school in the 1960s or in the 1970s we just don’t know any longer because they never made a career. Now, we live in an era where everything is very capitalist, and everything is only about money. I have to be honest, I don’t understand that. Art and career are two things that for me are in conflict, not in principle but on a theoretical level. If you are an artist, it should be all about creativity and freedom, whereas having a career takes a lot of that away for a lot of people.

I liked that you said that it’s a gamble. As a professor, I never saw myself as the guy at the poker table handing out the cards. It’s kind of an amusing image. But joking aside, I think you just put too much on an art school if you expect a career out of it. If you go to medical school, you have the expectation of becoming a doctor, let’s say a surgeon. But I don’t think you would expect to become the head surgeon at the most famous hospital in your country. I don’t know, maybe that’s not a good example.

But whatever you do, there’s no guarantee whatsoever that if you go to university you will have a fantastic career. It depends on so many different factors: luck, your own ability to do things, your parents’ money and connections, and it might even depend on whether you really want it when you go through it. I think there are a lot of discussions in the art world that I find a little bit unrealistic, and you wouldn’t really have them in other fields.

Ieva: You are also a writer and you run a very popular site on photography Conscientious, which you started in 2002. And I just wanted to ask, maybe, you can say a few words about what it is and how it has changed since you started it?

Jörg: At this stage, it’s a one-person magazine. It’s difficult to talk about because it changes – not all the time, but some of the time. I’m actually trying to change the programming right now, because I’m tired of only writing book reviews.

It all started 20 years ago. At that time, it wasn’t that easy to find art photography online. This sounds crazy now because it’s everywhere today. I was looking for photography, because I wanted to educate myself. And then I thought, well, if I save everything as bookmarks, then I’m going to lose all of them when I get a new computer. I put it in my blog so it would just stay there. In the beginning, it was this collection of photography that I had found.

Ieva: Like some sort of way of archiving in public.

Jörg: Sort of an archive or like a directory, where you can go, you see all these names, and you can look through it. In the beginning, there was no text other than a really brief description. At some stage, I realized that there should be more than that. I started doing interviews, because at the time I thought that a lot of interviews weren’t so interesting – I didn’t want to talk about cameras, and I thought that maybe I can do it differently. It has snowballed from there. I started writing. I’m not a trained writer, so I found out how to do it by doing it.

Around 2007-2008, a lot of people were blogging. It was really popular. But then the so-called social media arrived, and a lot of people went to Facebook. That was not for me. To be honest, I found Facebook too creepy and weird. So, I continued blogging. I also felt social media took too much of the content away, to replace it with promotion. I was and I am stubborn, I wanted content.

At some stage, I took away the directory part because it was so easy to find photographers online. I also was unable to maintain it because it was too much work with thousands of entries. I tried to focus on what I thought I can do best. This is how the current form of the blog came about. I started writing a lot about photobooks, because I was interested in them. Recently I realized that I also want to write about different things. I want to go back to interviews to make things more interactive and more interesting for myself again.

Ieva: I’ve also noticed that on the blog and elsewhere, you’ve highlighted a lot of work coming from this region – the former “Eastern Bloc”. Do you have any thoughts on what’s happening in contemporary photography here?

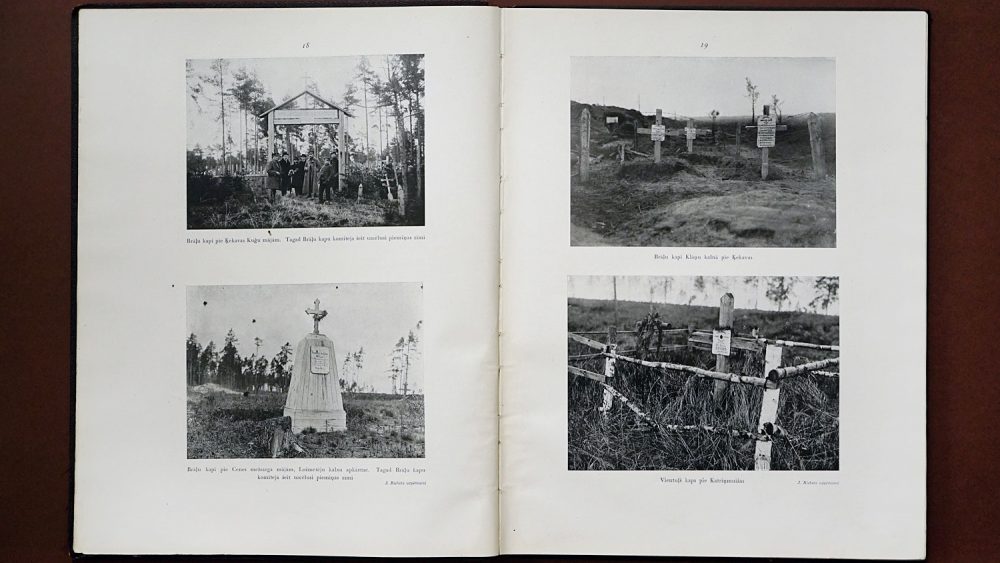

Jörg: I don’t know if I could call myself a real expert on the area. Let me start this way. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger wrote three books about photobooks. As I looked at them, I checked where are those books coming from. There were a lot of books from Western Europe, but Eastern Europe was completely underrepresented. The division of Europe into Western and Eastern Europe still exists in the world of photography.

For example, I think that Poland is a much more interesting country for photography today than France. There’s not really that much interesting photography coming out of France. I’m sorry if you’re French, but that’s just the reality. If you look at Poland or Estonia or Latvia or Hungary — there’s a lot of photography, with a lot of photographers.

Also, photography’s modernism was largely driven by Central European countries. I believe that the consequences of that are still with us. Part of the reason why I like looking at the region and visit if I can is because there’s just so much going on. There’s a lot of photography that’s still to be discovered historically. And there are a lot of young artists doing great, great work.

I think a lot of people in Western Europe are pretty comfortable, and that’s fine. But if you look at Eastern Europe, and I don’t want to paint the whole region in one big brush, but people in general are not as comfortable. It depends on the country, but there is still a lot of struggle over civic society and getting out of the Soviet condition. Or look at, for example, the authoritarian regime in Poland and photographers trying to deal with that. That’s something that people need to see.

Ieva: More on your writing projects – last year, you had a book published with MACK in their Discourse series. It’s called Photography’s Neoliberal Realism. And I thought that maybe you could just talk a bit about how you understand the term neoliberal realism and how do you think it relates specifically to photography?

Jörg: There were three things coming together with that book. One, I think there is not enough of deeper criticism of photography – right now a lot of it is very surface level. I don’t know if the book is deeper, but at least there was the idea to make something that also connects photography to our societies. I have always been interested in looking at photographs outside of the world of photography and looking at what do they actually do, and why do they do that. What do they communicate?

One day, I got a big box in the mail, and it was a book by Annie Leibovitz. That made me so angry. I thought it was really crap. I challenged myself to write about it – what is actually bad about it and why. One of the key discoveries I made looking at it was that everybody is treated like a hero, regardless of who they are. I think Donald Trump was already a president, and there was a picture of him in the book. There was also a picture of Harvey Weinstein, who at that time had already fallen from grace. Hillary Clinton was included, plus the people that were responsible for the financial crash in 2008. Everybody was in the book; powerful people, awful people, rich people in the United States. I thought that it is a form of propaganda. I tried to understand how it works.

I realized that the book is a celebration of capitalism itself. It celebrates the rich and the successful. There is this idea, especially in American capitalism, that if you work hard enough, you will be successful. This is often turned around. The argument then becomes that if you’re poor that’s because you’re lazy – that’s the talking point of US conservatives and the far right, which have now merged. It doesn’t have anything to do with reality, of course, because a lot of people have two or three jobs and are still poor.

I thought, okay, if that’s the ideology of capitalism and if you get to see the winners in Leibovitz’s pictures, then somebody must show you the losers. One morning, I woke up and realized – that artist is Gregory Crewdson, he is showing you all the losers. He doesn’t talk about his work that way, but in his photographs, you see all these dejected people. They live in these run-down mid-century houses, and there seems to be some sort of weird sexual frustration going on. Very strange. In Annie Leibovitz’s pictures, sexuality works in such a way that women are basically second-class citizens — they’re often depicted more like objects than people, but they’re celebrated because they’re beautiful.

I wrote about this on my site. Last year, Michael Mack invited me to turn it into a little book. And that’s what I did. At the time I was looking at Soviet art. In the early 1920s, there was a lot of really interesting art coming out of Soviet Russia – constructivism, El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko. All of that disappeared pretty quickly and turned into Socialist Realism. I had always wondered how was this possible. I read a book by Boris Groys. He describes the function of Socialist Realism and the way people would read these ridiculous looking pictures. They wouldn’t look at them as factual. Instead, they read the messages that were encoded in them.

I realized that it is exactly how this worked in the world of these photographers, where the real message is a code: the idea of success, of working hard, of not stepping outside of the system. That’s how it all came together, and that’s why I called it photography’s neoliberal realism.

Ieva: I think it’s interesting, what you said about the “hero” narrative. It exists not only in art photography or photography that’s being done for magazines, or newspapers, but also on social media. People want to make themselves heroes of their own life story and they want to show it to other people. And it becomes also a strange type of capital which is based on representation.

Jörg: You’re exactly right that the influencer is a variant of that. One thing that I have a problem with is that in the world of photography (“photoland”), selfies or influencers are denigrated. There may be some good reasons for that, but I think you need to understand this a little bit more carefully. I mean, I cannot blame somebody who grows up today for going down that route: all they see is that the people that are celebrated are rich people. There’s no alternative. We are not providing people with something different. The only things that matter today are fame and money. This is a part of the discussion that we should have — instead of complaining about selfies or influencers. It’s a bit like a world where there’s alcohol coming out of the faucets, yet we complain about people being drunk.

I’m not saying that this is the only discussion we should have. There is a lot in the world of photography that we should talk about. For example, we should talk about the idea that photographers need to go out into the world, whether it’s in their country or another country, photograph poor people, make expensive pictures, hang them in galleries, and then rich people come and buy those pictures. What is that? Where is that even coming from? That doesn’t help poor people, and it doesn’t do anything other than maintain a system that isn’t healthy. I am pretty sure a lot of photographers have good intentions, but we need to talk about this. Is this really the way the ecosystem of photography should function?

Ieva: But do you think art, contemporary art photography, or photobooks can change politics? There is a lot of also interesting work that’s being done about very political subjects, but what does it do?

Jörg: I can tell you one thing – a gallery show or a photobook that’s sold to other photographers or at an art fair is not going to change the world. That’s super obvious. One example that I usually give people right now comes from Poland. After the country’s abortion law was struck down and abortion became illegal in 2020, there were huge demonstrations in the streets. A group of Polish photographers got together and formed what they call the Archive of Public Protests. They made newspapers. The newspapers are free of charge, and they hand them out in the street and at demonstrations. They bring them back into the communities. I don’t think you can buy those newspapers at an art fair. Even if you can, that’s not their main purpose. I don’t know if this changes anything. But an expensive photobook that the same 300 people see for sure doesn’t change anything, right?

I like the idea of artists wanting to change the world. I don’t know how realistic it is. But I like the idea of trying to do that, because to me it says that somebody cares. I admire artists who care about what they’re doing. We should think about how else it is possible to bring photography into the world.

Ieva: Currently there is also more discussion about what makes an artist successful. Are you successful if you become this star, or maybe it is about working with your community of people that you know and sharing what you know? There’s a lot to think about, but many people who will decide to bring their knowledge to smaller communities or places that don’t get a lot of exposure, won’t be represented. It’s not a bad thing, but I think that it is hard for a lot of people.

Jörg: I have had a lot of conversations with a lot of students about success. I think you have to come to a definition of what success means for you as an artist. I’ve tried to tell my students that the first type of success you want to think about is artistic. If you do a project, success is that it does what you want it to do and that you learn something by making it. I actually think that might be more important than having a gallery show.

When you think about a community, and you make something about it and bring your work back there and show it, you have an audience for your work that you engage with. I would argue that’s also a form of success.

Ieva: I don’t disagree, but I do think that within our culture of social media and this “hero”-narrative, there is a way in which representation has become so important that it’s hard to sometimes imagine people doing something while not also trying to make the world know that they did it. And if the world knows, you might get more opportunities. There will be people, who do and will work this way, but I think that it means giving up a certain kind of an ego in a certain type of way that is not easy in this environment.

Jörg: I see what you mean. I always have to remind myself that I’m a little older and I grew up in a world where the idea of success was different. I don’t know what I would think about it if I had grown up in the hyper-capitalist world we live in now. I also don’t want to tell people what to do, but I do think that there are alternatives.

The worst part of the world of photography right now is that it’s a big competition. I don’t know whether people do it on purpose or not. It feels like everybody is competing with everybody else over the small amount of resources. That’s too bad, because I feel things should be more collaborative. The beauty of art is that you can connect with other people and create something deeply meaningful. If the system sucks you can either accept it, or you can try to create something different.

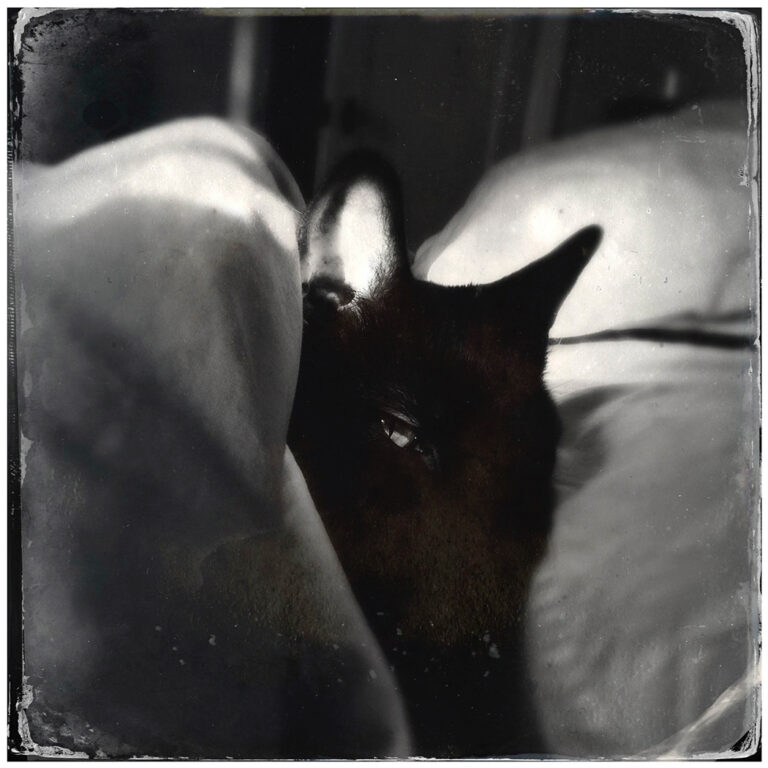

Ieva: There could definitely be different ways of looking at communality, sharing resources and interacting with each other. But to end the interview on a lighter note, I wanted to ask you about your social media. People who follow you on Instagram know of your love for cats and cat photography. A trusted source tells me that do you also run a separate account that’s dedicated purely to cat photography. Why do you think cats are a good subject to photograph? What makes it interesting to look at photographs of cats?

Jörg: Do you have a cat? I guess not.

Ieva: I don’t have a cat.

Jörg: If you have a cat, you just know. Pet photos have such a bad vibe in the world of photography. Supposedly, it’s bad to photograph your pets. But if you think about it, it’s actually really difficult to make a good picture of a cat, because a cat is always cute. I forgot who said it, maybe David Campany: the problem with a collage is that it’s really easy to make a good collage, but it’s very hard to make a bad collage or an excellent collage. It’s the same with cats — it’s very difficult to make a really good cat picture.

If you look at the history of photography, there are a lot of Japanese photographers who took pictures of cats. There are some really good photographs. But I cannot think of too many Western photographers that did or do the same. Mark Steinmetz is one. He has made some great cat photographs.

So when you have a really good cat picture that’s amazing. I love cats; but I also love looking at great cat pictures. They’re really hard to do.

Ieva: What are you working on now? You mentioned that you might have like another book coming out? What are your near future projects?

Jörg: I just finished writing a book, and I’m looking for a publisher for it. Half of the book is about photography, the other half something else. And it led me to the next thing: I always wanted to write a book that’s not about photography, but I never knew if I would be able to do it. Now, I know that I can. So I’m slowly working on a book that’s not about photography. It’s about a large number of different things. I don’t really want to talk about what it’s about, because it’s at the very beginning. But I’m really excited about it.