The (art) world of Adam Broomberg

The artist Adam Broomberg (1970) is best known for his over two decade long collaboration with fellow artist Oliver Chanarin (1971) that ended in 2021 with an official statement that Broomberg&Chanarin “legally, economically, creatively and conceptually committed suicide”. Their contribution to the art world is tremendous. The books War Primer 2 (2011) and Holy Bible (2013) that both deal with violence and the absurdity of conflict are essential publications in the history of photography. Broomberg has since continued to pursue various, collaborative projects that include activism, NFTs and a blockchain based project called fairfoto. A 40 minute conversation over Zoom was much about hypocrisy, hierarchy and believing in the good. A marginalized intellectual who has received online death threats for his words of belief and passion, Broomberg continues to defend his political and artistic interests in a new capacity.

He currently lives and works in Berlin. He is a faculty member of the MA Photography & Society programme at The Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Broomberg has had numerous solo exhibitions, most recently at Fabra i Coats Centre D’Art Contemporani Barcelona (2021), the Centre Georges Pompidou (2018) and the Hasselblad Center (2017), amongst others.

What preoccupies your mind these days?

I’ve collaborated on a collective project alongside Issa Amro – an artist and activist who lives in Hebron, Palestine. There are a number of other people involved all of whom have very different and essential skills. Ana Hernández has artificial intelligence expertise, we have someone (who prefers to remain anonymous) dealing only with cybersecurity. Batuhan Keskiner has uncannily unique practical skills such as biulding cameras from scratch. Another former student, Lena Holzer is and brilliant designer and thinker. We have Lina Aastrup with curatorial skills and we are now working alongside Tezos on a project using blockchain guided by Christian Nolle. It’s quite a big group of diverse people, based throughout Europe and Palestine. We’re working on a number of projects that all intersect and involve conceptual art, photography and activism but they are all very practical projects that have an affect on the ground.

Is it Artists + Allies x Hebron?

Yes, so for our first project we’ve installed a number of surveillance cameras throughout olive groves. They send a live stream to various institutions and to a website that we run. It’s open to the public, so they can take care, cast an eye and make sure that the trees are okay because they are attacked by Jewish settlers and by the Israeli authorities. What’s the gaze of a surveillance camera? It’s a very philosophical thought, of course. We wondered what could constitute a counter-surveillance gaze?

You would imagine there would be an eye looking back at that camera, but we wondered about the drive behind surveillance? It’s about control, it’s about maintaining power, it’s about humiliation because you’re robbing people of their privacy. We thought, counter-surveillance could be more interesting when it’s a benevolent gaze. It’s not about breaking, it’s about building and servicing the community. So instead of an aggressive gaze back, it’s rather a very gentle gaze using exactly the same technology. It’s a camera’s gaze at things that are happening live. The cameras were placed to ensure that these trees which are up to 3000 years old, are safe, because they’re very important economically, socially and spiritually to the community. It is a very conceptual idea, as well as very practical.

There’s a few more projects that we’re starting to work on now, for instance, one that uses the blockchain. We have access to a very high-resolution satellite imagery of Israel and Palestine. And we’re currently training an artificial intelligence algorithm to be able to identify an olive tree from any other tree from above. Then the algorithm will also be able to estimate the age of the tree, as well as the geolocation which means that we can identify who the owner of the tree is because, all the Palestinian farmers have title deeds to their land. The age of the tree, the owner of the tree, and the location of the tree will be listed on the blockchain. When I was little, sometimes, as a birthday present, I would get a certificate of adopting a koala bear in Australia, for example. For $100 you were feeding the koala bear for five years and you got a picture with the koala bear and its name. We’re going to offer people the same experience – they can adopt a tree and that money will go back to the community. It helps to maintain, again, the safety and security of the tree and I think it’s interesting to be able to put in the lo-cation of your tree and to see it in high resolution on the website. Maybe you get in touch with the local farmer or the family that owns it. You can actually be in correspondence. We are co-opting the technology for a more positive use.

You are proactive at addressing political conflicts, war, injustices – does it come from a socially and politically active citizen or an artist?

They are not separate. I grew up in South Africa under apartheid. I remember at the age of 16 or 17 al-ready collecting images from the archive of the biggest hospital in Johannesburg because it was world famous for people. Doctors would come from all over the world to deal with gunshot wounds and knife wounds. That archive was already politically charged and I was very interested in it. If you look at all the work that I did with my former partner Oliver, there’s never been a separation of politics, life, or art. It’s all been very connected. The difference is that previously the practice was more manifested as wandering geographically and I think that now it is focused more on building a long-term relationship with a place and with people in the community. I think that’s something that’s really been missing for me. To make artwork that actually has a profound effect on people’s real daily lives.

You are also active on social media, mainly Instagram. How effective are the social media plat-forms in communicating important issues?

It’s been effective and helpful. I have almost 40,000 followers and I get a lot of information from it. I’m also able to publish a lot of information too but it’s so clear that my account is shadow banned. Whenever I talk about something that is particularly sensitive, it’s seen by much less people. It’s an effective soap-box. In England, every Sunday in Hyde Park corner, there is a so-called Speaker’s Corner, people go and stand on a box to shout their opinion. It’s a bit like that on Instagram, you’re shouting and screaming, but it’s a bit like shouting into Plato’s cave. In the end, I use it as a tool, it’s helpful to get technical support or to find particular skills. I try and use it in the best way but I don’t have much expectation from it or have any emotional relationship with it.

There was a recent clash on Instagram after you commented on Vogue’s photoshoot of the Zelenskyy couple. Do you like controversy? Your opinion seems to stir up one. What was the main disagreement about?

It was very interesting. I didn’t expect that kind of massive response, nor the ferocity. My whole practice is based on interrogating images. It doesn’t matter if they are on the Rice Krispies cereal box or they are in Vogue magazine, I always interrogate them and that’s what I was doing. But I hit upon a particular nerve, and it showed me many things. First of all, the level of patriotism in Ukraine and also the reactive nature. One can understand, you have people whose very existence is threatened and that’s when you react like that, in such anger. However, I also received a lot of death threats for making an academic comment that I constantly do about other images. This war exposed a lot of the hypocrisy of the world and also something which I call the hierarchy of empathy. I created a fundraiser right away as the war happened.

Exactly. We raised a lot of money that went directly to art and cultural workers who are at risk, fleeing Ukraine. I managed to get 150 of the world’s most recognized artists to give work as an open edition which normally they would never do in an instant. That is because this was war in Europe. If I was asking for money for refugees fleeing climate change or conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa and trying to cross the Mediterranean, there is no way I would get that response. It was because these were white Western refugees, and it doesn’t mean that their pain is any less. I worked alongside a dedicated team of people for four months, full time on that fundraising. I was also at the train station where up to 2000 people were arriving per day in Berlin. This war has generated the same number of Palestinian refugees in the world. Seven to nine million and nobody talks about Palestine even if it’s the same amount of suffering.

I found those images and the whole narrative around the war very disturbing, because it makes the assumption that a war is a given and that somebody’s going to win this war. Nobody’s going to win the war. Nobody wins wars. There is a pathological dictator, threatening a country and there has to be a defence or a push back, but nobody’s going to win this war. Nobody won the First World War, nor the Second. They’re still going on.

Why is human race so obsessed with war?

I can only talk about photography and its relationship to war. That (Vogue’s photoshoot, ed.) was a perfect example of how photography enables a certain narrative, which is, in this case, the brave heroic man, his female counterpart whom he defends, but she also enables him, there is a kind of sexy beauty to it, which we see in photography. There’s always a certain degree of sexiness. Even in the writing. The way the Spanish Civil War was written about by Hemingway, it’s the same thing, right? But if you look at the writing of the amazing Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexandrovna Alexievich, she writes about war from a feminist perspective, not of the men who are engaged in the battle. It’s a very different narrative. I read that there was a lot of correspondence of female journalists during the Spanish Civil War that was just published. It was again a very different narrative to Hemingway’s. There’s an assumption in photography and in journalism, that being at war is just an inevitable part of being a human. There’s also some tendency to glorify or romanticize it and I think those photographs did that. For me, that is dangerous because that makes war inevitable.

So long as there are men, there will be wars.

Well, this is what my father said during the apartheid to his children who were activists: “This is just humanity whom you’re fighting against.” I think if you don’t believe in progress, then you might as well just die. We’re in such an interesting time now, because most of Europe is fascist. We’re living under this extreme conservatism, and at the same time, we have a generation and my children are in that generation who see the world in such different ways. It’s so beautiful, progressive and inclusive. I have a lot of hope.

You don’t lose hope for a better world?

I do. Like everyone, I totally lose energy. But I think that’s why I like to work with a group of people because then somehow, we keep each other going. If I had to rely on myself only, I think I couldn’t do it.

You are a big advocate for Palestinian rights, however you’re marginalized in your attempts for help. Do I understand correctly that your initiative to create a campaign for Palestinians similar to that for Ukrainians didn’t get the support?

I understood that I need to put my energy into what I believe and where I most focus even if it’s like swimming upstream. It’s almost impossible to raise money for this project, however, we have fantastic ideas, an amazing team of people. If this was a pro-Israel Zionist project, I would have millions by now, I would have the whole Hollywood behind me. We are building a GoFundMe project because I’ve run out of money. It’s again, the hierarchy of empathy, and that depresses me a bit. Because, especially in Germany, they’re too scared to fund something like that.

So, there is fear that exists in the art world?

Absolutely. I did work around Israel and Palestine in 2005. I had a show at ICP, in New York, and then we got sued for accusing Israel of ethnic cleansing. I never really had a career in America. Palestine is just a swear word in the art world. I think that’s going to change because you’ve got a new generation, many Palestinians who are being recognized internationally for their work and identifying as Palestinian. I think it’s just a matter of time. More and more young Jewish people are coming on tours to Hebron, getting to understand what’s going on around them.

How much do art institutions want to get involved in political projects and issues?

It depends on the issue and the country. Identity politics are all the rage in America. LGBTQI+ is not very popular in Poland. But it seems the Palestinian occupation is one universal no go in any country. We asked almost 200 institutions to take part in our olive tree project, only 4 agreed.

An instagram post by Adam Broomberg made in Hebron in the Occupied West Bank, June 3, 2022.

Does being a Jew gives you a protective shield when criticizing the Israeli State?

Quite the opposite. First of all, historically, any Jew that criticized Israel was called an anti-Semite. My entire family apart from my grandparents were wiped out in the Holocaust. I live in Germany, I experienced apartheid, and I identify very much as a Jew. It’s only recently my family are starting to accept some of the work I make, like this last project. When I made a book called Chicago in 2005, my father begged me not to publish it, saying that I was betraying the Jewish people. I don’t think I’ve been very protected to be honest.

Looking at your Instagram, I get a feeling that you have a lot of retrospective moments lately – analysing and criticizing the photographic media and your own role there in the past. What do you mean when you say that the traditional photographic practice, technology and experience was toxic?

All of photography involves a relationship that’s just a one-way flow of power. The person behind the camera is in control and has all the power over the economics, distribution, and narration. I’m very privileged to be able to look at my work and say, what was wrong and to show people what is wrong. I feel it was work very much of a moment where there was that narrative that documentary photography can be a force for good, that bullshit thing of giving a voice to people without a voice. Give me a break! That’s just rubbish. Everybody is quite capable of speaking up for themselves!

Are these the ideas where Fair Foto was born from?

Yes that is about taking care of the person in front of the camera. That’s another project that uses the blockchain. I think it has a real potential. Adobe has already done something called the content authentication initiative which means that they are registering all the metadata attached to a digital image on the blockchain. They are just not including the person in front of the camera in the contract or in the metadata. Photography works with copyright, which is very outdated. Other art forms now work with Creative Commons, which is a more agile and much more expandable or adaptable contract and practice. Copyright just says “check, you own it forever, bye bye”. That’s crazy. You can’t own somebody’s image!

Do you believe that art can change the world or can help in changing the world?

That implies there’s art and then there’s the world. What’s the drive behind the artwork? Is it ego-driven? Is it about getting your name celebrated? Is it about making money? Or is it about revealing the complexity behind being alive, about giving other people a sublime experience or insight into a place or a space you have explored or invented.

What is your drive?

It’s changed over time. Mine was about as toxic as you can imagine. It was very ego-driven, very arro-gant and very entitled. I had very much a white male’s swagger. It’s only in the last while that I’ve come down, I’ve landed on the ground and trying to become humble and to be of service. Feminist politics would say “the personal is political”. The mother of my children often says that I am very good at doing the world politics, but how about the politics within the domestic space? In those terms I’ve got a long way to go.

Is that the reason why you’ve stopped the long career with Oliver Chanarin? You seem to still like the collaborative form.

I’d rather not even talk about the past. I talk about that in my therapy, I don’t need to talk about it in a magazine.

Where does your interest in NFTs lie? Going with the trend or you’re interested in technologies per se?

The idea of registering the Palestinian olive trees, that is a NFT. What we considered NFTs for a couple of years was nonsense, but I have always understood the radical potential of the technology from 2017. What we need to think about is a non-fungible token as a contract. In this case, it would allow the Olive Tree Project or Fair Foto to use the technology according to its real function. It’s not just trade in Pokemon cards as JPEGs really, I think that’s kind of over now, thank God. I know the people who bought the thing for 69 million and it was all about crypto trading and inflating a currency. The market was all just false promises to young artists. I think the art world’s snobbish response to NFT’s was about the aesthetics and the politics, which I think is appropriate, but I think it’s going to still be a very big part of the future. I think that the blockchain and the tokens will now start becoming interesting projects even though the market is still wanting figurative photography or figurative painting.

What are the biggest problems in the art world?

There are many art worlds, and I’ve removed myself from the ones that I find most toxic, which are the ones driven by money, ego, power, money laundering, false economies and bloated ideas of talent, and it’s a very big relief to get out of that. It felt like a mixture of gambling and selling your soul, like literally sitting at a blackjack table and having to flirt with the croupier, needing the croupier to say how great you are. A double nightmare. I’ve had many dinners with the most horrific people until one day I said I had to get away because I didn’t see myself in this art world. I’m not sure it was so elegant and conscious. I think I made myself so distasteful. Like when you have a splinter in the skin, the skin just gets rid of it. I think that world got rid of me as opposed to me elegantly turning my back on it. I’m not exactly the most popular person in the art world. I think I’ve insulted pretty much everyone there is to insult. Some of that I regret. I mean, I could have done things a lot more elegantly. But mostly I am at peace.

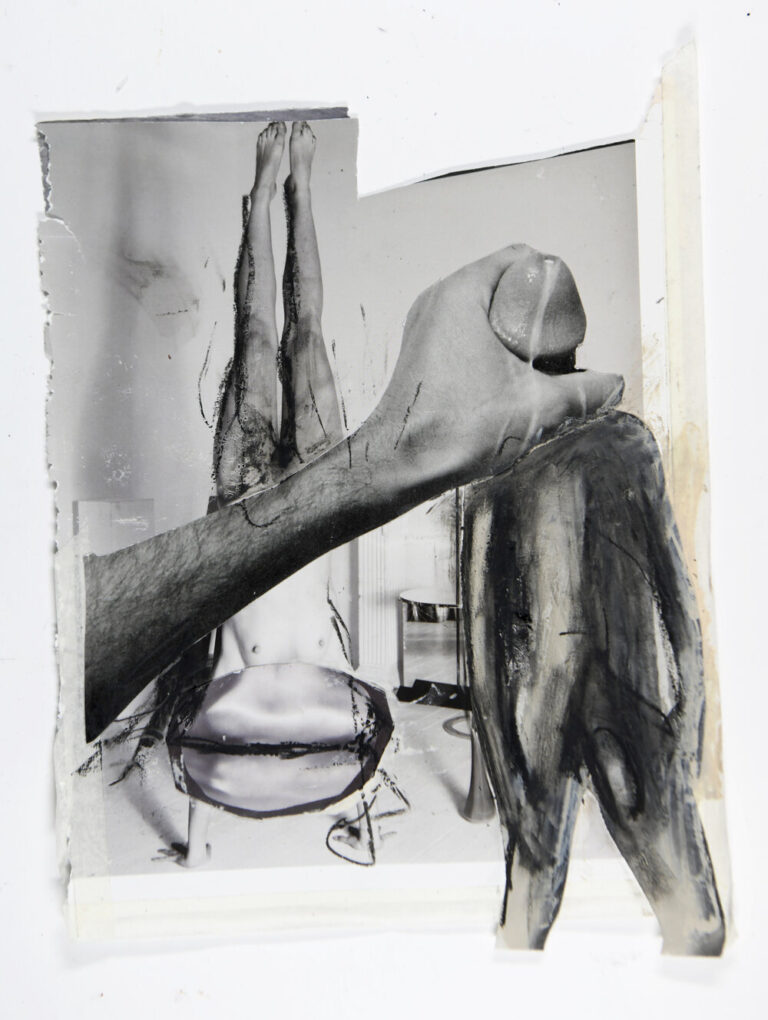

Cover photo – Adam Broomberg, New Viewings 26, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Photo by Batuhan Keskiner