10 minutes with Lindsay Seers and Keith Sargent

Lindsay Seers and Keith Sargent are an artist couple from Kent, England. They have been working together since 2012, creating large-scale installations across a variety of media and formats. Their work has been exhibited at venues such as the National Gallery of Denmark, the Venice Biennale 2015, Kiasma in Finland, the Tate Triennale in the UK, the Taipei Museum of Contemporary Art in Taiwan, and many more.

This year, Seers and Sargent are participating in the Riga Photography Biennial. Their exhibition Vamp(yre) Reality is on view at Riga Art Space until 2 June. “The works unfold in the making as in an act of performance. One thing leads to another. It is only fully realized in the exhibition hall, a punctuation in the continuity of the works’ evolution,” says the exhibition description.

What is the main idea of the exhibition Vamp(yre) Reality and how did it come about?

There is something inherently vampiric about photography. It has a status of being frozen in time (a vampire can live forever) but also absent (not seen in a mirror). There is a seminal book called The Vampire In The Text by Jean Fisher, which has influenced our work.

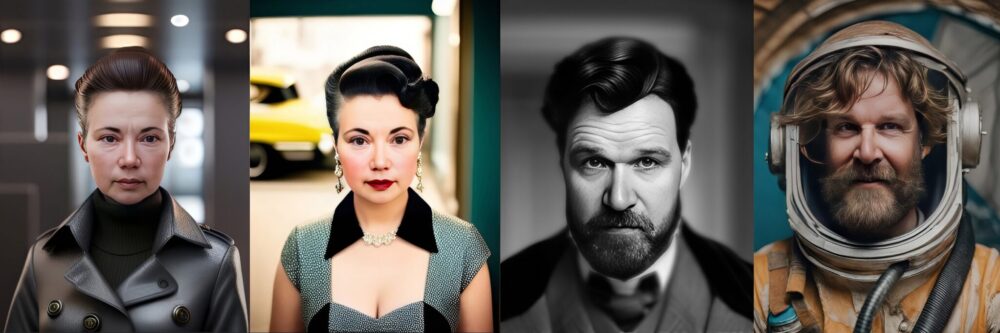

Another point about the name of our exhibition in Riga Art Space, Vamp(yre) Reality, is that we took a cue for a wordplay. The AI program would switch to a holding screen whilst it processed the mouth movements which said REVAMPING REALITY. It was close to the word “vampire,” so we pushed it. The speaking photos were almost all from a photograph album we found in Riga. Those pictured were all three generations back and more.

Another point of vampirism was that our practice has been shaped by becoming a human camera, which started around 1994, whereby I used my mouth cavity as a camera obscura and various blackout tents and bags whilst I ingested an image. The photos with colored paper went red with the light passing through the corpuscles in my cheeks. The pictures were literally colored by blood. These mouth photos are in the back of our exhibition room behind the transparent curtain.

The description of the exhibition states that the work of Henri Bergson pervades your practice as a method. It also mentions that you push photographic programs to their limits. Do the viewers of this exhibition need to be somehow specially prepared?

We have been greatly influenced by Bergson due to our interest in consciousness. We hold a strong belief in the complexity of thought in Bergson’s philosophy. He was one of the most famous people in the world, and masses flocked to his lectures. However, he was derided and forgotten over time. “Creative Evolution” endured. Philosophy fuels our works. However, Bergson was skeptical about photography. In his book Matter and Memory, he asserts that no matter how many pictures you take of Paris, you will never truly know it. Instead, he emphasizes the importance of stepping out into Paris, smelling the air, and feeling its essence. Additionally, he is the only philosopher who offers advice on how to raise consciousness in an individual.

The theme of the Riga Photography Biennial this year is the essence of humanity and the role of the image in the face of the challenges of the 21st century. What do you see as the biggest challenges of this century?

The extent of images is beyond reason. It has long been the case that people have manipulated imagery that has led to murder, imprisonment, or persecution. But with the rise of algorithms, we are trapped in the limitations of programs essentially written by humans – it is evolving but dangerously. The problem is that we are animals and tribal. We easily digest false truths without evidence. What is currently happening now in terms of all the wars is that the weapons industry is keen to make millions of dollars to enrich the billionaires while slavery and poverty are rife.

You work with different media and objects. What role does photography play in your work?

Regarding the objects in the work, they often involve large theatrical structures and extensive soundtracks, with many films, smoke machines, and roving lighting. But these structures point towards the spectacle we are still living in. There is irony in the work and Brechtian elements. There is no absolute truth in an image. However, it was famously brought into law as evidence in court, but many did not believe it was justified.

What are your thoughts on AI entering the field of art and photography? Do you use it in your work?

Yes, we are very engaged with AI and algorithms, but with some horror. Eventually, probably all will be decided by them. But it is unknown if there will be a backlash and humans will not want to be slaves to a (algo)rhythm but make their own individual personal decisions. Even making this text, I am irritated by the AI suggesting words that are incorrect.

What have been your biggest recent surprises or discoveries in photography?

We visited the Museum of Occupation. The history of the Baltic States was not one I was familiar with, but the photography and installations, both employing actors to vividly depict events, were overwhelming and devastating. Museums are advancing with their ambitions.

What are your creative plans for the future?

We are working on new pieces with our robots and structures, but we are also trying to advocate for artists who don’t have commercial galleries behind them to be paid for their work. In the UK, arts funding in our major galleries has been eroded. We can only look to Norway as a model for Europe. Football and theatre are the UK’s main funding streams for culture.