First World Problems

At the moment, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize exhibition is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. This prize has been awarded annually since 1997 to a European photographer for an outstanding exhibition or publication, and it is regarded as the most prestigious photography award in Europe. In fact, the prize fund — £30,000 for the winner — is more generous than the Turner Prize, whose recipient receives “only” £25,000. The winner will be announced on 15 May, one month before the exhibition closes.

This year, four artists have been shortlisted, and notably, two of them are nominated for books. This is a reminder that the photobook can be just as significant and authentic a medium as an exhibition. In photography, there are numerous competitions and showcases dedicated specifically to books or dummies, such as the Paris Photo/Aperture Award, the Dummy Award, or the Arles Photobook Award — the latter featuring notable Latvian publications last year. A photobook can function both as a collectible art object and as a democratic medium that makes images accessible to a wider audience. Furthermore, in a country like Latvia, where photographic institutions are weak and cannot ensure the acquisition or preservation of works, the book can become an important — sometimes the only — tool for safeguarding cultural and artistic heritage.

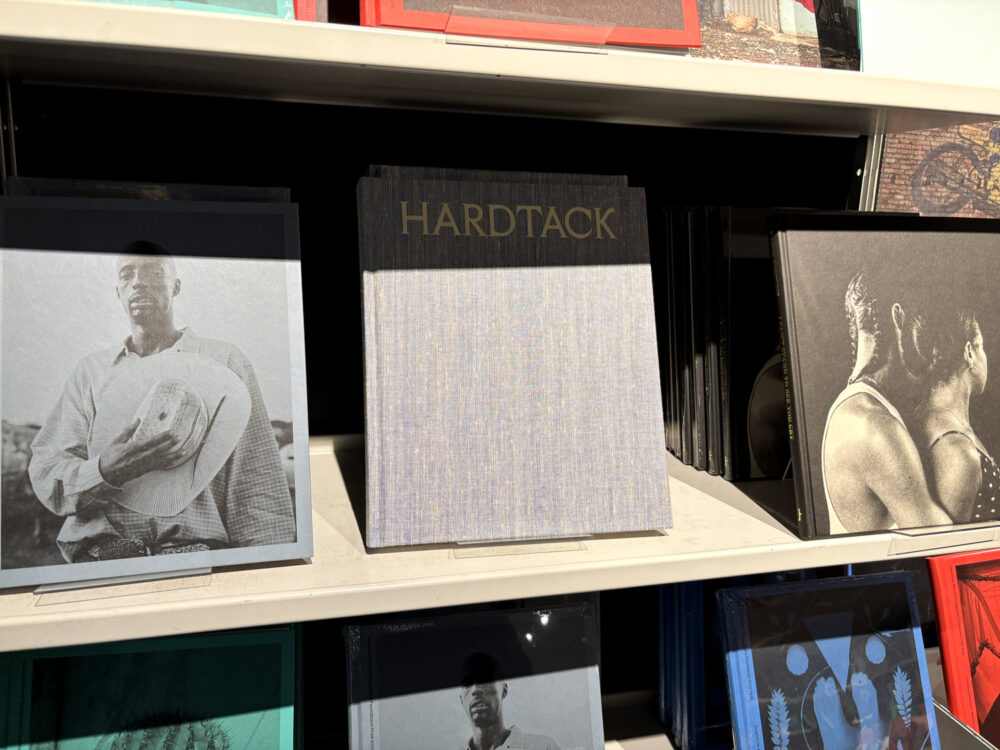

The prize exhibition is spread across two floors of the gallery, with two artists on each level. The first impression: everything is very orderly, correct, understated, classical, unambitious. The American photographer Rahim Fortune is nominated for his book Hardtrack, in which black-and-white photographs document African American cultural traditions and family histories, exploring migration in Texas and the southern United States. The book itself can only be found in the gallery’s basement shop, while the series is presented as an exhibition. One can understand why — the book is modest: a standard layout with a simple cloth cover. The author presumably wanted the design not to overshadow the photographs. Yet it’s clear that such a book could not stand alone in an exhibition context; it would be eclipsed by almost any photographic work. Even the prize’s exhibition catalogue seems like a more ambitious artistic object than this book.

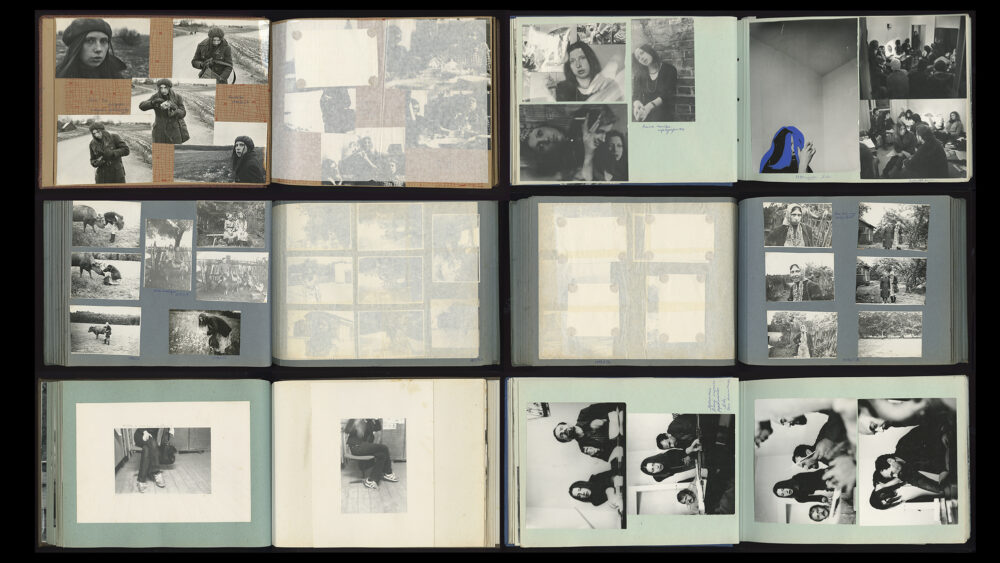

South African photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa is nominated for his book I Carry Her Photo with Me, which could be seen as a family album. The book itself is neither displayed in the exhibition nor available in the gallery shop, but the works are arranged on the walls in collage form — at varying heights, formats, and sizes. Black-and-white portraits, photographs combined with drawings, and diary projections attempt to speak not only about the photographer’s family but also about broader themes of poverty, social fragmentation, and the ongoing impact of colonialism in South Africa.

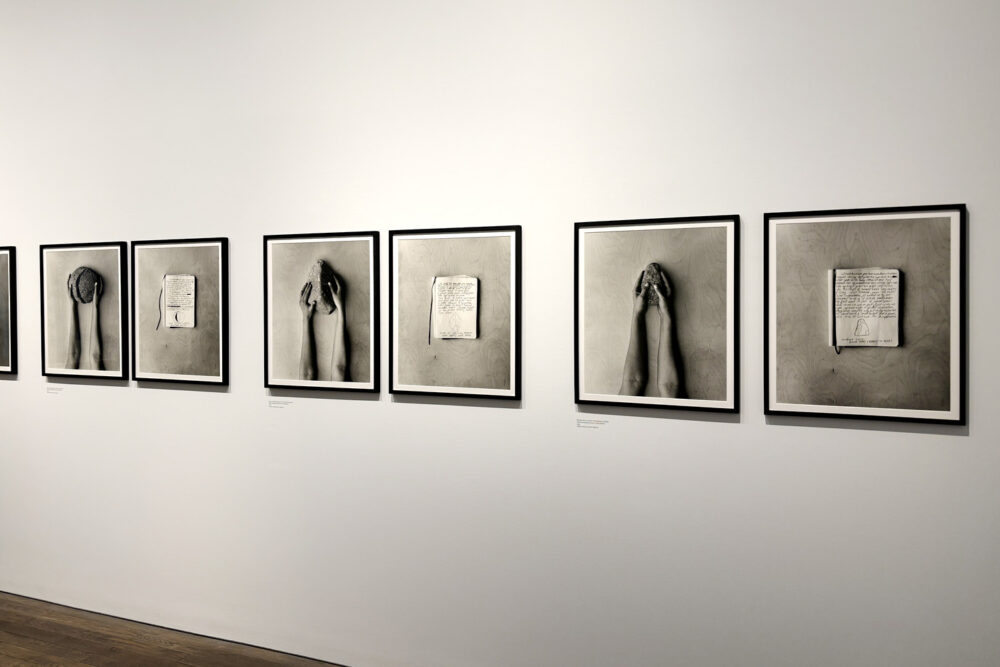

Peruvian-born photographer Tarrah Krajnak uses the camera as a research tool, blending staged self-portraiture with performance, blurring the lines between theatre, investigation, and self-reflection. The exhibition text states that she challenges hierarchies of gender, race, and class, though this is most visible in one particular series, where she parodies nudes by the American photographer Edward Weston (1886–1958). Other cycles, featuring stones held in hands or cyanotypes, fall somewhere between decorative imagery and opaque psychological introspection.

Spanish photographer Christina De Middel is nominated for her exhibition Journey to the Center, presented last year at the Arles festival. It follows migrants on their journey from Mexico to the border town of Felicity, California — a place sometimes described as the centre of the world. De Middel takes a forensic approach, collecting not only portraits of people but also objects found in the desert — a comb, playing cards, scissors, and more. She also incorporates tarot cards and archival material to complicate the narrative and reflect the uncertainty of real life. In Arles, her exhibition was impressive, occupying a vast church space; here, of course, her allotted area is just half of a relatively small gallery space, and it inevitably loses some of its impact.

This exhibition, in which all four artists explore themes of migration, community, belonging, and historical trauma through Latin American, African, and African American experiences, raises questions about the prevailing agendas of the global art scene. There’s no doubt that these works are deeply personal, politically significant, and artistically strong, yet I find it difficult to identify with them. I do not find references to myself, to my region, its cultural landscape, history, or current affairs. Once again, it seems that “our” global problem is the legacy of Western European colonialism, illegal immigration in America, and the aftermath of apartheid in South Africa. Of course, global powers are busy compensating for the injustices of their colonial pasts, but this happens within the framework of their own historical memory and priorities — leaving other regions, whose histories are equally tragic and complex, largely ignored. This is especially apparent in relation to the post-Soviet space, whose experiences are still rarely part of the global art discourse. Even now, with the war in Ukraine ongoing and the surrounding region living in tension and uncertainty, Ukraine has already faded from the international art world’s spotlight. Yes, a couple of years ago Ukraine was prominent in photo festivals and art fairs, but now it’s almost as it was before the war — something marginal. But who cares about us? Would the last oppressor of our region ever be prepared for cultural self-revision? While the heirs of colonial empires are currently re-examining their histories and attempting to create new narratives, in Russia such reflection has scarcely existed — even before the war. This leaves us with a paradox: while the Western world works to decolonise its culture and acknowledge the sins of its past, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics are left to wait until Russian museums and galleries decide they are ready to confront the consequences of their own imperialism. That seems about as realistic as imagining a Latvian artist making it to the finals of this prize. And yet, only a year ago, to even speak of an Oscar for a film from Latvia was pure utopia.