Culture first, then the rest. Interview with Robertas Narkus

Robertas Narkus (1983) is a Lithuanian interdisciplinary artist working with performance, photography, video, collage, text and other media. He is interested in efficiency, irony, power, science and freedom, to list just a few topics in his hybrid art. He is playing and being exceptionally serious, always looking for the answer to what it means to be an artist. Latvian audiences saw his works in 2017 in a solo show Guest at Contemporary Art Centre kim? in Riga. Narkus is also the founder of the Vilnius Institute of Pataphys-ics, the artists’ daycare centre Autarkia and the experimental engineering camp eeKūlgrinda. He will be representing Lithuania in the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022 with the project Gut Feeling in which he intends to set up a functioning cooperative combining artists, scientists, local Venetians and small businesses.

Tell us about your background – how did you become involved in art? What did in-fluence you to become the artist that you are today?

I think I knew I wanted to be an artist from early on. I clearly recall that I was interested in ninjas and hieroglyphs. Somehow I thought that I had mastered the hieroglyphs; I knew how to write my name, my brother’s name and then every kid in the yard wanted to have their name written in hieroglyphs. I believed that I knew what I was doing and everyone somehow continued to live with these Japanese names. I don’t know exactly how it translated later into art but I think it has something to do with believing in things. It offers a certain explanation of the way I look at what I’m doing now. Then I studied art – I took art at school and I went to the Vilnius Arts Academy, Photography and Media Department. And then some years later, I also studied at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam.

What is your relationship to photography? Did photography somehow reach its limits for you?

In general, I find myself quite a clumsy person in terms of dealing with anything materi-al, sort of a cow in a porcelain store. Photography keeps a certain distance from the reality, I can’t really break things with the camera.

But you can break the camera!

I can break the camera, easily! I think it was in the early 1990s, we got this point-and-shoot camera for my mother’s birthday. I was super excited about it as well. And then I went to the school trip with it. I was taking pictures, and really enjoyed making these, what I thought, fantastic images of the castles. And then I came back home and realized that I had lost the camera along the way. But that feeling of capturing stories remained. When I was in the 11th grade, I quit the school and went to the United States of America. I worked in restaurants, earning some money, so I bought a camera and started taking pictures. I came back in the middle of the last year in school with a clear idea that I wanted to study something related to directing or camerawork. Then I chose photography and media art. I worked intensely in the commercial field and somehow I thought that I would be able to combine both, the more experimental practice with commercial jobs. Unfortunately, this quickly turned into industrial work, which was a good experience; I learned a lot. I also discovered the corporate world but pretty soon I realized that I’m not able to combine these two directions. So one day I just said to my clients that I’m no longer available. That, I think, also changed my relationship to photography. I always attempted to fight the medium. I wanted to reinvent it from the technological side, presentation, printing. These attempts were interesting. It might seem that I stopped taking pictures at certain moment, but it was always part of the practice. It just remained as some sort of device to fix the moments and stories, but not necessarily as a primary medium – rather, as a final destination.

It’s interesting that from, probably, well paid commercial photographer job one day you quit to be an artist. How do you survive as an artist without having a day job?

The commercial world was good. It laid a certain foundation, and this experience allowed me to understand that there is not so much to lose. I became a much more risk-accepting person, and this was one of the steps that I have never regretted. And at the end, it paid off. We have this saying “when you have teeth, there will be bread”. Whatever I am engaged with, I still try to prove that there is not so much to lose.

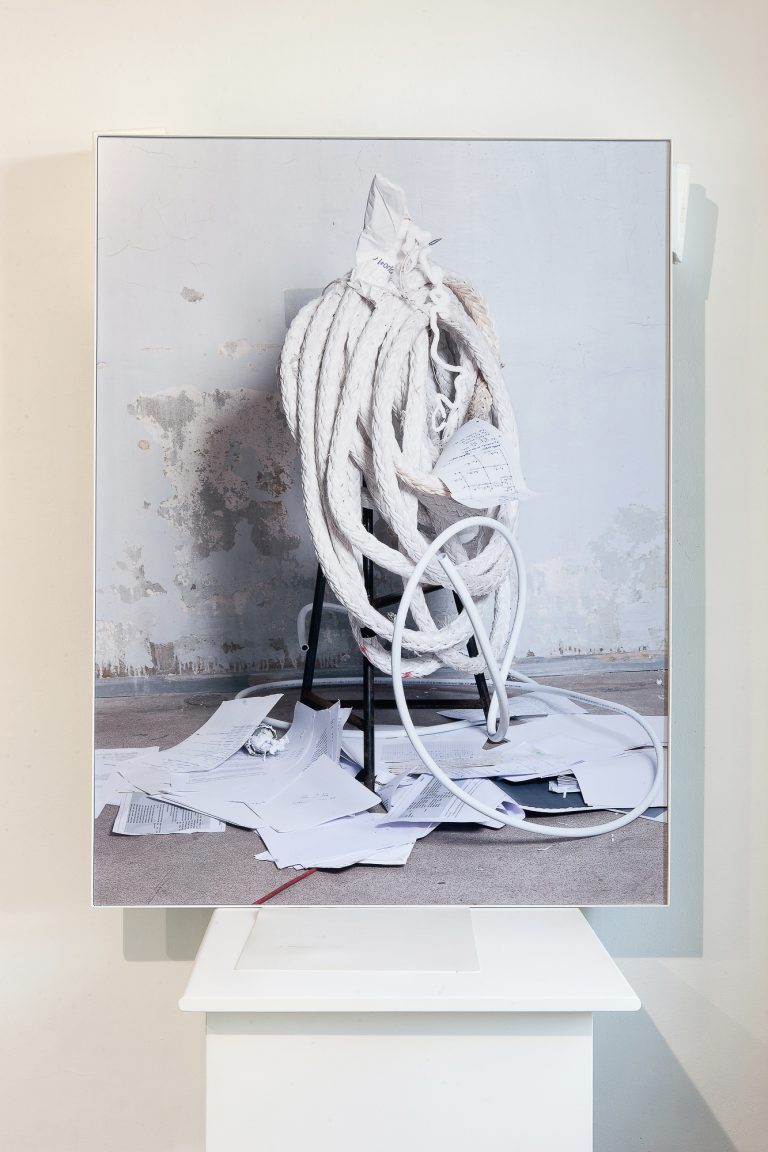

Your work The Board is a certain return to photography. Why did you decide that a photograph of these intricate, sophisticated compositions that almost feel alive will be the final form of the artwork?

You’re right, I sort of returned to photography as a medium and it has to do with a term “quality” and how often it is used, as well as craft. I really wanted to push my visual imagination to certain limits and see how far I can realize these very immediate sculptures. It is a very entangled and interconnected set of concepts that are embedded in this project that have to deal with control, or decision making on starting from the title and the setting of the exhibition to the choice of camera and the way that photographs are arranged in the space and the way you walk through the space. These sculptures are intense in the composition, the fabrics, and their physicality. Yes, I wanted them to have a presence, but also with a certain distance and a parallel reality. There is no glass, they have a sturdy metal frame, and they are installed in the space in a way that people can see both sides. So they came out almost also as an object. I’m interested in how far I can get from the image that is on my mind into this final image that is an actual photograph. It’s a very narrow interest, but I am interested in decision making, it also addresses certain art taste questions.

What does it mean for you to be an artist?

It is one of the questions that I’m trying to answer, to solve. Is it image making? Or whether it is a direct political involvement? What can it be? But in general, I still think that the obligation of an artist is to do what matters, to fight for freedom, to protect the freedom and be brave.

Do you mean freedom as an artist or freedom in the world?

Both. Freedom is something very difficult to describe but I mostly mean freedom of choice. Being able to question things outside the narrative and the system, when every-thing seems to be clear.

Are there any expectations for the artists?

There are all sorts of flowers and stones in the world. They are not obliged to somehow respond to their surrounding. Artists are not supposed to do something or to somehow be, it’s just a question of certain consciousness and conscious understanding or trying to understand your relationship to the world, to your community, to your friends, to your country, to nature, and this relationship can be meaningful in many different ways. It’s personal, from a person to person, from an artist to artist. I don’t think that there is that much of a big difference between artists and non-artists. But it’s a certain understanding that you will focus on trying to understand why you are doing what you’re doing. It can be meaningful to engage in a very kind of totalitarian way and trying to solve the problems as they are. But it also can be very meaningful to create works that are just pure joy or have nothing to do with big problems.

You do both, don’t you?

I think I’m trying to do both. Sometimes these attempts are funny, sometimes they are sad, and sometimes tragicomic.

I think that the art world doesn’t have enough humour but you definitely have a lot of it, maybe even sarcasm, in your work. It was refreshing to read the statement on your website. Instead of this serious, very similar way of presenting what you do and how you are as an artist, you present an apology letter to art.

I think that a smile dismantles unnecessary barriers and helps to reach and tell certain messages much faster and in a more direct way than explaining. Artist is a humorous occupation, even the most serious art is funny when you think about it. I never think of it consciously, like constructing humour. Maybe good humour happens by accident. Although it’s not accidental. I guess I am contradicting myself. It’s a professional management of the accidental that makes the humour. In terms of irony or sarcasm, or even criticism, I think it’s not that I seek for those things, most of the times, but I am sincerely engaging. And if this irony, somehow happens as a side effect, most of the times, it’s directed towards me and my situation. I’m rather trying to understand my situation in the world, and then trying to understand the motives behind the decisions that I make. Sometimes it coincides with the surrounding world and the drives that are around. When you look deeper and deeper on what we really fight for and what we want, it’s not that funny.

Some of your recent work seems to have a reference to an idea called “elevator pitch”. Why?

I call my practice a management of circumstances. I deal with economic realities. At cer-tain moment I was exploring the corporate world. It’s not that I am in particular interested in this language, but I think it somehow dictates and influences so many layers of our reality and the way we behave. There’s always a lot to explore how the capitalism is actually affecting us. So, the elevator pitch is one of the phenomena of how to be efficient. Efficiency is also one of the subjects that interests me as a concept. Efficiency in communicating as we have to say things shorter and shorter and in a more direct way otherwise we lose interest. I was going through hackathons and startups and co-working places while working on this project Prospect revenge, which is based on the how I saw people pitching their ideas, in a very similar way as artists have to pitch their ideas quite often. And based on both, excitement and frustration, that is within this elevator pitch phenomenon, I built a performance and other pieces where the elevator pitch went too long or wrong, for instance.

What are the pros and cons of the art world becoming similar to tendencies in econ-omy or other areas where we need to be quick, successful, proactive, always present?

Over-professionalization of every aspect of our life has a certain toll. It really drains a lot of joy out of life, out of occupation, and sometimes you even might forget, why you are doing what you’re doing. I tend to consciously catch and warn myself but then it is also very professional to see yourself from this other perspective. So it’s a loop that you are in and it’s difficult to escape. We think of our image so much that we even forget why we do what we do. This inertia is something that I tried to if not to fight then to take into account. There is a certain beauty in this industry. It’s also like a game which you have to be able to enjoy. There is no way you can play it if you don’t enjoy, otherwise you will become tired really soon. Yes, in art too, you need to be responsive, you need to be present, you need to know things; you need to be eloquent. I think that, besides all the skills, you also need to have luck to be an artist, it’s crazy. At the end, it’s not so much different than other domains. If you look at this professionalism as something that allows you to grow, it’s part of the journey.

If you would write the rules for the art world, what would they be? What would be your game?

I hope it’s not chess (laughs).

I was thinking about the pandemic, and how a lot of art institutions had to close their doors, and some of them forever. Art is still on view only through windows, online, slowly re-entering the outdoors spaces. Do you think that somehow reflects the place of art in the society?

I think there are a couple ways to look at it. On one hand, I think art can be looked at as having very high ethical or moral standards. It means that you cannot bargain about the necessity of art in this sort of situation. Art world should be able to continue running and inspiring in different ways and trying to reinvent ways to experience the beauty and the truth. Maybe this is romantic, maybe the reality is that the political will is not fully comprehending the power that is within the culture because economy doesn’t mean anything without culture. “Everyone is an artist, but only artists know that”, this is written on the wall of the Contemporary Art Center in Vilnius. To a certain extent, I think people are not really aware how interconnected the things that seem to have nothing to do with art are. People don’t even think how art and culture affects every field and how it actually is pushing and making you present in the world. When you see the countries that have achieved something, it’s usually the countries that are based on culture. Everything else follows. You can have resources, but if there is no culture, it’s stagnation around the corner.

Artists also need to be taken care of. How did the idea of Autarkia, the Artists’ Day-care Center, come to be?

I think that a big part of being an artist is trying to find yourself in the society, in the community. Artists are quite often “the other”, therefore I’ve been engaged in this at-tempt to create environment for the communities to emerge, for people to encounter each other. Artists’ Daycare Center is one of these places in Vilnius that is sort of a social hub, not only for artists, but for various interests, and sort of a safe space for things to go well. Or wrong. It is also a meditation on what an artist is and what the project space should do, what the art institutions are, what a “culture center” means today. Artists’ Daycare Center is closely intervened with the concept of being self-sufficient. It’s also a gathering of people pursuing their own interests. We facilitate different opinions and try to facilitate a certain growth and a very different meaning of the word. We are operating in space that used to be a secret Soviet space programme factory. Now, the loft area and our “headquarters” is what used to be a canteen. We run a restaurant, where we also employ artists and the restaurant is also an entry point to broader audiences who slowly realize that this is something more than a canteen.

Do you think about your audience in any stage of art making?

We live in these bubbles where everyone understands what they do. But when you step out a little bit, then you realize that people look so alien to understand what we are actually engaging in. I want to offer an access. I believe that a good artwork has many gates, that it is possible to experience it through many different layers, although not all art has to be necessarily understandable. But I do care about it.

Gut Feeling that will be shown at the 59th Venice Biennale, is like a peak of your in-terests of combining not only different subjects, like art and science, economy and politics, but also engagement. Can you talk a little bit more about what Gut Feeling is about?

You’re right, in a certain way, Gut Feeling amalgamates a lot of different subjects that matter to me. It is being planned to happen in the streets, in the alleys of Venice, as op-posed to a clearly defined gallery space. It will spread to local stores and closed stores, and laundries, and restaurants and other small spaces that belong to people. I cannot say that I will work with people, but we will try to find a meaningful relationship, to basically make a deal. I hope that our presence there, in a working class area, will bring the art world to their lives. This encounter is a very subtle situation that I’m putting myself into. A lot of different conflicts, and also friendships, are possible. And again, it’s a quest for me to understand what the artist is supposed to do. I don’t know yet how it is going to end. This is a concept, it is a new work and I’m very glad that I’ve been trusted with this project. Someone is also following the same gut feeling that I have and taking the risks. It’s about a certain state of mind and mobilization. What matters for me, is also the experience that the visitors will have. Will these multiple layers be comprehensive, will the project communicate with them? I’m trying, we’re working hard to put these many different ideas that are out there into something that can be accessed through the art forms.

I guess that is that freedom you were talking about earlier? They trusted you, you give yourself enough freedom how to finalize that work. It’s the freedom of being an artist and of communicating your idea. I guess everything is going according to the plan?

Yes, there is a plan, it seems like it’s going according to the plan (laughs). I am just try-ing not to lose the connection to this idea. There is some frustration that can impact your decisions and artistic freedom. This possibility of the many possibilities is enigmatic and inspiring. I hope to translate that feeling too.