Art helps society to breathe – interview with Darius Žiūra

Darius Žiūra’s (1968) exhibition Portraits is on at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius until February 19. Its four pieces reflect on important concepts to Žiūra such as portrait, time, space and society. As atypical as it might sound, Žiūra talks about the importance of discipline in his work manifested through observation and participation, repetition and repetitiveness. A minute long portraits that have been made in his native village, portrait series that reveal the first generation born after Lithuania regained independence, a monument for friendship that started during the military service in the Soviet times. Žiūra invites to look and think about the rules, the role of art in society and the message of a portrait.

Darius Žiūra is one of the leading Lithuanian artists of his generation, who primarily works with photography and video. He has studied painting and has a PhD in Fine Arts (2017) from the Vilnius Art Academy. He has participated in Manifesta and Kaunas Biennale, as well as in numerous solo and group shows.

What are your childhood memories?

My childhood was split between two different worlds. I was born in the countryside, in Joniškėlis. My parents were studying in Kaunas and they didn’t have a place to bring me up, so they left me with my grandmother in Gustoniai for five years. Sometimes they came to visit me but they looked like beautiful aliens from a completely different world. I lived with my grandmother, surrounded by love and nature for five years. Then my parents got a brand new flat in the block district in Kaunas and they took me to the city, where everything looked strange and surreal. The milk tasted artificially, the concrete environment had no nature, there was violence, propaganda and strained family relationships. It was like a modern story of Mowgli when you take a wild child from a jungle and try to make him a social person. It was quite a traumatizing experience for me. I was waiting for summer to come when I could finally go back to the countryside. I thought that I would grow up and return to live there but my life turned out differently. I got education, got involved in cultural life and became an artist.

Do you still feel a connection with this place? You have made a video portrait series Gustoniai here.

This project was born from this connection. I always wanted to depict this place but never really succeeded. I remember I was trying to paint some motives of Gustoniai when I was studying painting, but was never satisfied with the result. In 2001 when I went there for the first time with a video camera, inspired by the idea to film every person living there, I wasn’t really sure if it would work. It was a big question if it was possible at all, to come to a person with a camera and say “Stay there, I will film you for a minute”.

But you were a local.

I was sort of a local. To the village people I was a guy from the city and it was quite difficult to explain what I was doing in life. Another thing is that filming really differs from taking a photograph. People are more used to be photographed. But here, they saw a video camera for first time in their lives, and to be in front of the camera for one minute, without any scenario, it can look strange.

What has changed in terms of how you see the project Gustoniai since you started it in 2001 and came back with new video portraits last summer?

In 2001, when I went there for the first time, only “true villagers” were living there. This was still the place of my childhood, with the gravel road, water wells and the same people. Over time, some people from the city had bought houses and they also became a part of the project. In these eight films you can see the life of a person and the story of the village. You can see the history of Lithuania and all the post-Soviet space. Then you can make connections with geopolitical processes here. It’s a certain micro cosmos in which you can see a reflection of something much bigger.

Did you ever get to photograph your grandmother?

I took a few photos of her but not in this project. She died when I was 15.

Why did you choose to take a minute-long video instead of a photograph?

I was always interested in making a discussion, creating a dialogue with established formats and representational traditions. One minute portrait reminds of a photograph, yet it has a duration. It is very much about photography from a critical perspective, although it is not photography itself in a sense of media. It is interesting that American art historian George Baker began his work on his famous article “Photography’s Expanded Field” at the same time when I began Gustoniai. It was like hacking the ideas floating in the air in different parts of the world.

How can a photographic portrait tell a story?

Photography is maybe the most popular power tool to catch the likeness. The photographic image has a pretension of being objective but it’s always a battleground between objective information, subjectivity grounded in the media and a subjective artist’s perspective. For each portrait you choose time, place, weather conditions, lighting, the background, the depth of field. Each photographic portrait is made with a specific camera and lens and presented in a particular way. Each portrait becomes one of countless choices possible. This inevitably shifts the photographic portrait into a fictional level, where reality becomes altered by the subjective artist’s vision and the conditions dictated by the visual parameters of the media. After all, the photograph looks like it’s an imprint of reality, but it is dead. This tension between different contradictory factors provokes our imagination, makes us think and create missing parts of the stories in our minds. A photograph is silent, but you can imagine a lot. Like these one-minute portraits. Some of them are almost still. If you sit and you get into this one-minute rhythm for longer, you get some story in your mind, it’s quite fascinating. They look like silent interviews. People tell you a lot about themselves just by looking at the camera instead of telling one-minute stories in words.

How did you get into photography and how did you develop special interest in portraiture?

Maybe let’s start from the portraiture. At school, from 36 children in my class, only two could draw. It was a distinction, you feel that you can easily make something that others consider very difficult and sophisticated. I remember my first portrait project. I was maybe 10 years old. It was still too difficult to draw a person from the front but I discovered that I could draw a profile. I got a special book and had an intention to depict all the classmates in it. I drew one profile on each page, and each of them was a real achievement for me. I did nearly half of the class, but my teacher confiscated the book because I was doing that during lessons. I was so desperate to get this book back but the teacher didn’t give it to me on any conditions. After lessons, I was following her with my classmate, with the intention to find out where she lives and smash her windows with stones. It was dark autumn and we got in the same bus, it was full of people. But her next bus was empty and we just couldn’t follow unnoticed so our plan failed. But I still remember this book and it was probably my first conscious attempt to make a sequence of portraits.

So, it was kind of a natural way for me to go to arts and I got into the art college after the 8th grade. But applied art was not something that gave me a higher sense of meaning. I left my parents’ house quite early, surviving from a monthly scholarship at the college and started to do oil painting on my own. This was something special! Many of these early paintings were portraits of my friends and girlfriends. These adolescent years of active interest in painting eventually brought me into painting studies at the Department of Painting at the Academy of Arts in Vilnius. A famous question at the Painting Depart-ment was – “who do you want to be – a painter or an artist?” The painter was an absolute priority. But I wanted to be an artist first. I was interested in ideas more than in formal problems of painting. I started to create my own rules about how to do painting without actually doing painting. After a lot of experiments I came up with the idea to cast objects from wax and created a conceptual sequence turning painting into 3 dimensionality. With these series of works I got the prize at the Students Art Days show, one month studio in Paris and that was a starting point in my artistic career. But after I graduated from the Academy it was a dead end. No money, no place to live, no place where to put art. I started to work with video. An entire film could fit into one small video cassette and you could project it on a huge screen. It was fascinating. The only problem was that video technology was still at an early stage of development and the image quality was relatively poor. Photography at this time had a bigger poten-tial. That was how I got to photography.

How would you describe your main interest in art?

There are two main topics – time and a human being, two main problems which are unsolvable. All kinds of art, based on reflection, such as visual art, cinema, theater, literature and philosophy, have a certain potential for making a meaning in otherwise hopeless existential situation. It reminds me how mushroom mycelium works in nature. We know that it plays a crucial role in the ecosystem splitting different types of matter into elements consumable for plants, which consume those elements and produce oxygen. Art does something similar in society, it generates a meaning. If you took culture away, society would collapse.

Do you think there is enough initiative in Lithuanian cultural policy to support artists, cultural workers?

Not enough, of course. I think it’s a problem in the entire post-Soviet space. The accent is on the economic development, whereas culture is of secondary importance. If you compare the private business sphere and cultural sphere, cultural one is always lower – from project funding to salaries for teachers, museum workers and cultural workers in general. The situation is problematic. I only can hope that it will change gradually for the better, but apparently it is a very slow process.

How do you support yourself as an artist?

I am doing a full time job as an associate professor at the Photography, Animation and Media Art Department of the Vilnius Art Academy. Since January I have been enrolled into a post-doctoral fellowship for two years. I’m constantly studying, teaching, practicing, sharing the knowledge.

How often do you take a portrait but later decide it “doesn’t work”? What needs to be in a portrait that it would reveal something? How much does it depend on the photographer, how much is it the sitter’s personality?

In this show we see 24 pairs of portraits. In 2005 I was photographing with a middle format analogue camera. From photographic tapes to processing, scanning and printing everything was costly, especially for the artist, working on a non-commercial basis. And especially for one who took this kind of camera in his hands for the first time! I was taking just a few shots of every model, trying to be as precise as possible. I had my understanding, how photographic portrait should look like and there were a lot of disappointments, such as slightly wrong exposure, unsharp focus and other flaws, which I was considering as mistakes. But now as I see them again after 17 years, they all look beautiful. These photographs are not that much about technical brilliance but about the idea, time, certain phenomena that already is part of the history. So now I see them quite differently. All these portraits from 2005 with all their flaws and imperfections look even more alive. You can see them almost like a symbolic end of a pre-digital era. Something that will never ever repeat itself again. And a lot of portraits that didn’t work for me 17 years ago, now work perfectly because my intentions, perspective, references have changed over time.

The next photo of the same person was taken in 2021-2022 with a digital middle format. We usually went for a walk for a couple of hours, sometimes taking a few hundreds of shots. When you work with non-professional models, every photo session is different. Sometimes you can take 500 shots, but the first shot looks the best, because of an emotional state of the model, which you cannot recreate. Sometimes the last shot looks better, because the model gets tired enough to abandon all the manners of posing and finally starts to look more natural in front of the camera. Sometimes the best photo is somewhere in the middle. To make a perfect shot is always some kind of magic, that you never know if you will get. Each time you begin from zero and have the same feeling, that you are not quite sure what to do. Everything seems completely messy, the light is problematic, the background is terrible, and you don’t know how to make the magic work. But the magic is very relative there. 17 years ago, I also had some picture in my head how the portrait should look like. And now I kind of also follow an intuitive model. After another 17 years this picture will look different again. Obviously, we can’t predict how the world will look like and what technologies will be created, what the political situation will be like and how all this will affect our image of the world. I never discard my drafts. I make some choices for a particular show, but never say that some of them are bad and “don’t work”. For me, the project as a whole is more important. It is kind of a living organism, which develops and grows in time.

Are you planning on revisiting them again?

I would like to make a third part, in 15 or 16 years. Of course, it is quite a long way forward, but I sincerely wish to see that time.

Since you tend to photograph for your projects over a long span of time, what are the important changes in society and in the photographic medium that you have noticed most? What changes are you keen about, which ones make you sad?

Back in 2005 I could travel through all the country with the camera photographing children, and nobody ever made a problem out of it. It was the time when there were no smartphones and the internet was still a rarity in the countryside, and there were no social networks yet. I had a feeling that it would change radically quite soon. In one interview I described this time as the sunset of the camera innocence. Very soon after 2005 Facebook exploded and the world was digitalized tremendously, and with this came privacy scandals and problems with data protection. Photography was criminalized. Children were absorbed into monitors of smartphones and computers, and disappeared from the yards, and 25 percent of young population from rural Lithuania emigrated. Now to make such a project would be extremely difficult because of legal issues and because there are less children in the countryside. I was lucky to catch something at the moment when it was not yet too late.

Speaking about the photographic medium, in 2005 there was still no digital camera which could beat a good quality middle format. It seemed just impossible. But the last 15 years of digital revolution opened possibilities for film and photography, unimaginable before. Meanwhile, the analogue format reminds of a prehistoric era. Something beautiful, warm and nostalgic. Now the photographs look sharp, colourful and clean, but in 15 years they will inevitably be perceived like a testimony from the ancient times with quite a primitive technology.

After all these years and projects, are you still a country person or have you become a city person?

I’m a city person with a slightly split personality. To me, the countryside is different from how the people who live there perceive it. They are much more pragmatic about it. For me it is a recreational space where I’m spending a relatively small part of my time. Making art consists of maybe 10% of creative practice and 90% of planning, organizing, communicating, writing projects, and lots of rather technical work, which is not visible in the exhibition spaces. I simply cannot imagine myself doing all that in the countryside. Being in nature, just blows my mind, I cannot concentrate on management anymore.

Can you talk about your concept of discipline in art? What is it?

In people’s imagination an artist is a kind of mystic personality, driven by the freedom of self-expression. The special individual, who denies social gravity and flies above the grey crowd. It is one of the most deceitful popular myths.

My practice is grounded in continuity, and I have to develop certain discipline. It can take an undefined amount of time to fulfil some ideas. You have to limit immediacy and simply can’t get too emotional in conflicting situations. I recall the story of Monument for Utopia. Russians occupied Crimea in 2014. One year later I went to St Petersburg and found myself in the environment of euphoria, that Crimea finally belongs to Russia and Putin is the right guy in a right position. Slava was a passionate supporter of the regime and deaf to my arguments. His studio was big and busy, several projects were going on at the same time, different people were coming, doing work, drinking tea together, discussing politics, and everyone was imperialist. I didn’t hear any other opinion. Radio was broadcasting sinister optimism and Colorado ribbons were on the sculptures. It looked totally surreal to me. If I tried to argue, figuratively speaking I immediately got bricks flying to my head from different corners of the room. There were a few times when I felt fed up, I thought I would just close the door and go home from Saint Petersburg to Vilnius, just to get out of the situation. That was one of the moments, when urgent need for immediate freedom nearly killed the discipline. But nevertheless we were working on the monument, waking up, going to the studio, sometimes not speaking to each other for all day, and it was like being on a mission. And finally we did the sculpture. After a couple of years, Slava himself got into conflict with the system and emigrated to Italy with his family. His views changed radically. All his friends remained in Russia and now they simply avoid any contact with him. He became a traitor, infected by Western ideology, who can’t explain anything to anybody on the other side of the border. And now he says Darius, please, forgive me, I was so stupid… So, discipline is like taking a deep breath and going underwater. You cannot always engage in a play, which gives you momentary satisfaction. You are like a marathon runner.

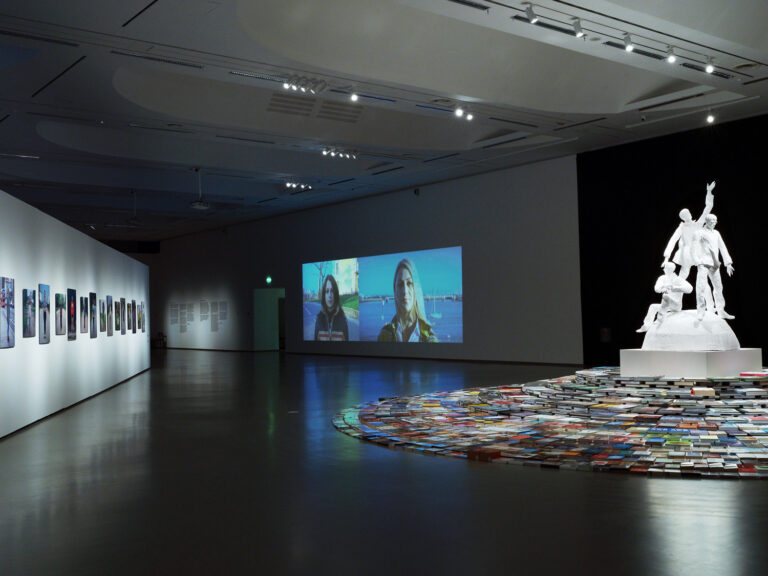

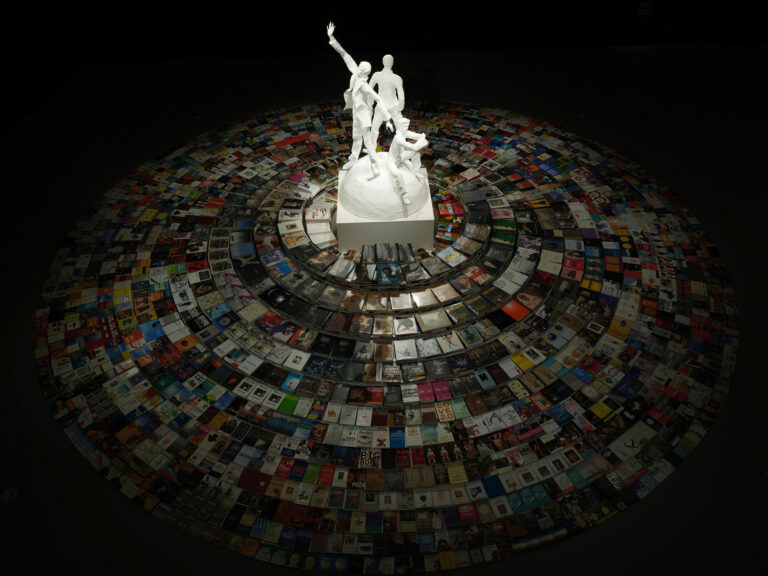

Can you tell more about the Monument for Utopia? It’s about three friends who met in the Soviet army.

In 1988–1990, I did my military service in the Soviet Army. I spent two years in the city of Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East, near the border with China. It was the time when the National Revival Movement, Sąjūdis, was born in Lithuania, which eventually led to the declaration of independence. I happened to be part of the last generation of Lithuanians in the Soviet military. Serge (a Latvian) and Slava (a Russian) and myself (a Lithuanian) were three close friends, sharing similar interests in life style, music and visual arts. Formally, we belonged to general troops, but in fact, we served in a separate ‘club’ section. We had skills in calligraphy (Serge), photography (Slava) and painting (myself), and our daily routines were slightly different from those of the others. We were the creative unit of visual propaganda. After the military service, we split to different directions. Serge moved to Dublin, immersed himself in explorations of the gay scene and spent the best years of his life doing unqualified jobs at supermarkets while somewhat obsessively using his savings to buy lottery tickets. I got in touch with him in 2014 and was astonished to learn that one of his occupations was a systematic theft of books from bookstores. According to him, he did this with no pragmatic purpose. It was more like self-therapy, a kind of intellectual fetishism or a solipsistic effort to domesticate an alien cultural environment. During his emigration years, he had stolen almost three tonnes of books. Part of his collection was irreversibly lost. The remaining part of it consists of art books, indicating his constant interest and systematic self-education in visual arts, and also an extensive collection of self-help books, as well as books on cooking, poetry, neuroscience, psychology and various casual topics.

Slava had well-developed professional skills in photography and was working as a freelance correspondent for the youth magazines Kostyor and Ogoniok before his military service. In the Soviet era, photography was heavily underrated in contrast to the respected ‘pure art’ like painting and sculpture. After the military service, Slava took exams to enter the Photography Department at the prestigious Moscow University, but he did not show up at the beginning of the studies and was expelled. That was a critical point in his life when he abandoned his dream to become a photographer and started his career from zero. After a few years spent on persistent training at the preparatory art school, he was accepted to an art college. After three years of studies, he entered the Sculpture Department at the Repin Academy of Arts in St Petersburg. Eventually, he became a prominent sculptor in this city and taught sculpture at the Repin Academy, promoting the school of Russian academic realism.

Inspired by those radically different, yet symptomatic, stories, I began thinking of how to connect Serge’s stolen books, Slava’s sculpture in the style of Russian academic realism and my ideas into one piece, reflecting on three different personal trajectories after the collapse of the Soviet Union. I proposed to Slava to commemorate the 25th anniversary of our friendship with a sculpture, leaving the freedom of interpretation to him. I went to Saint Petersburg and helped him to materialize his vision: three figures looking like portraits of the three of us, standing on a symbolic globe and facing three different directions. The sculpture is surrounded by the collection of over two tonnes of stolen books. We were born in a state that does not exist. Russian academic realism is not interesting to anyone outside Russia and looks comical. Motivational books, which currently occupy a significant part of the offer of every bookstore, do not work. In the collection of stolen books an entire personal drama is inscribed – the field of interests and unfulfilled ambitions of an intellectual, the history of addiction, the attempt to tame a foreign cultural environment, the longing in the emigrant’s soul. The sculpture embodies a familiar visual scheme. Soviet cosmonauts or other propaganda heroes could be depicted this way. Everything together forms a combination of seemingly incompatible elements, permeated with self-irony. The amusing absurdity of this composition is probably the essence of this work.

It is not easy to find information about you online, you don’t have a website. Why is that?

It’s not a principal choice, I just always had more urgent deadlines. But the website is scheduled for the end of 2024. So, it’s coming.