Latvian photobook: Year of Horror

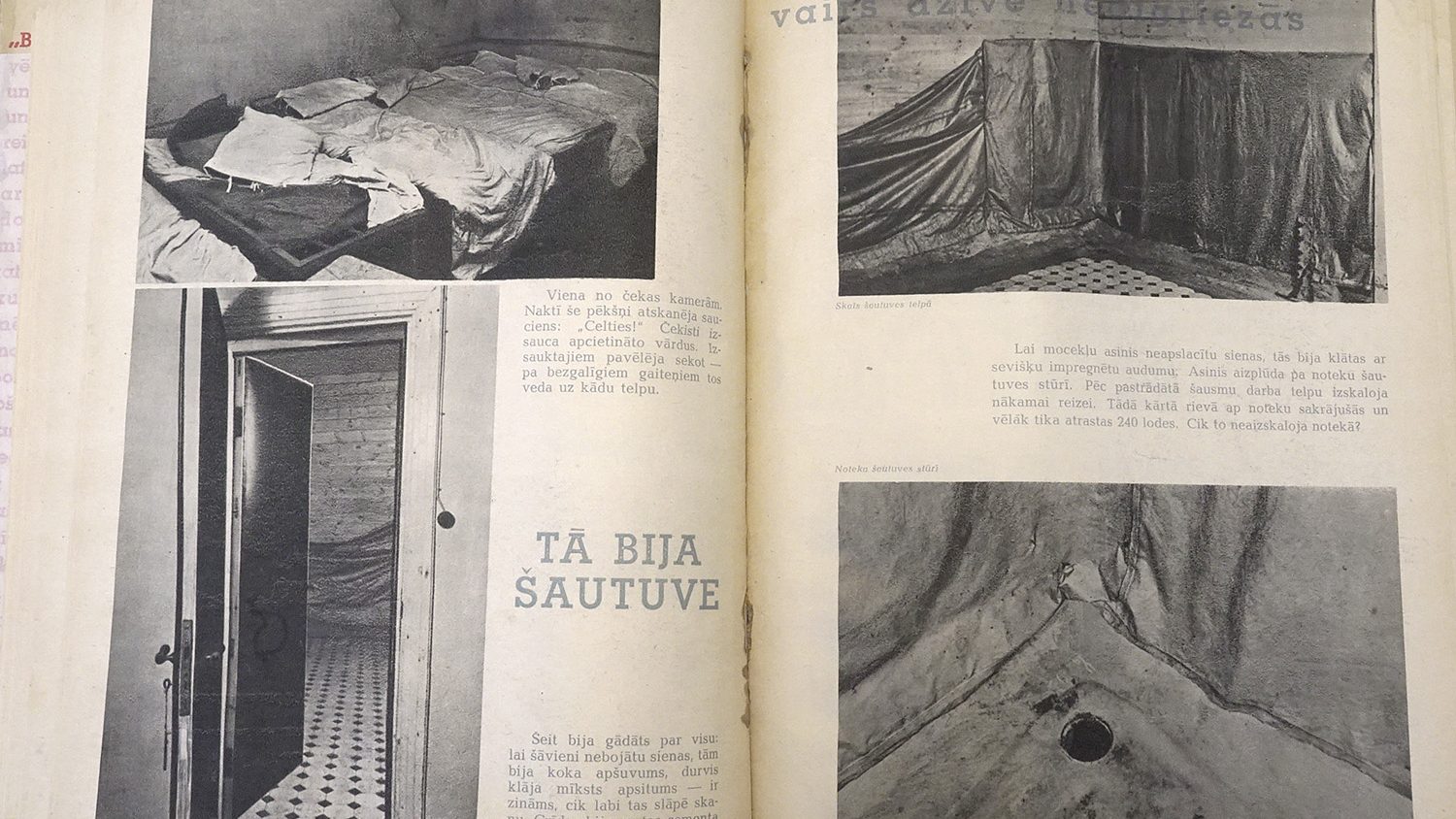

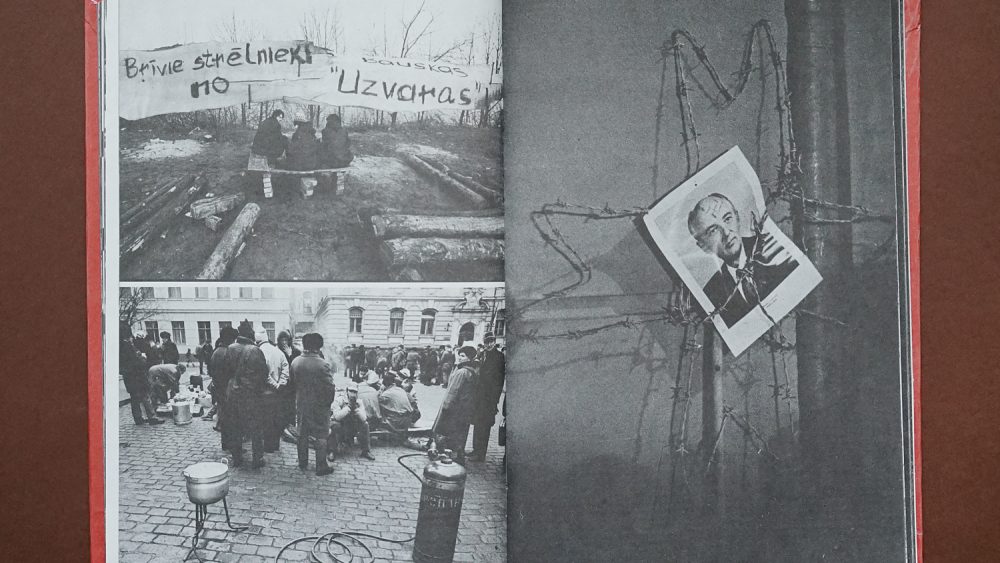

The 1942 book Year of Horror (Baigais gads) published during the German occupation consists of photographs from the first period of Soviet occupation in Latvia (17.06.1940–1.07.1941), known under this name in the history of Latvia due to mass deportations and murders.

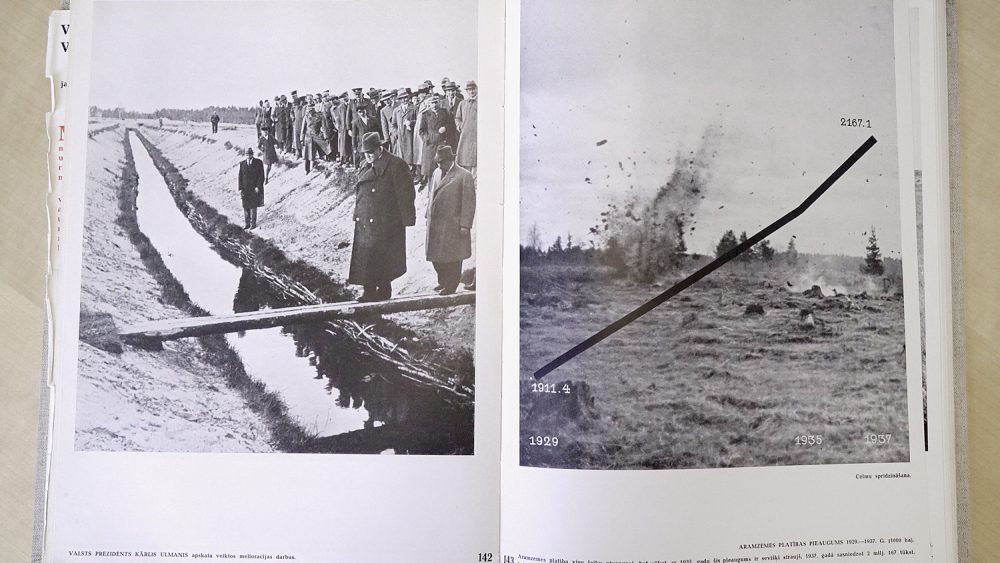

The 96 page- book was issued in 25 000 copies by a team of editors: writer and publicist Pauls Kovaļevskis (1912–1979), artist Oskars Norītis (1909–1942) and publisher Miķelis Goppers (1908–1996). The authors of photographs have not been indicated. During the German occupation Kovaļevskis was editor-in-chief of daily newspaper Fatherland (Tēvija; 1941–1945). The task of Fatherland was to promote the activities of the German regime both on the frontline and in Latvia, as well as to support anti-Semitic propaganda. In this context the work with the book can be viewed as a natural side project. Norītis, in his turn, was a respected book designer of the time. Goppers could have been engaged in the project due to personal reasons – in 1935 he founded the publishing house Zelta ābele, but along with the Soviet occupation in 1940 the work of the publishing house was interrupted; Goppers’ father was imprisoned and shot in the forest near Ulbroka in 1941. During the German occupation the publishing house started functioning again and Year of Horror was issued simultaneously with some other books. The book was also published in German (1943), and several facsimile issues are available (1988, 2003).

The book presents photographs in which we can see the Soviet troops entering Latvia, street demonstrations, the elections of Saeima (Latvian parliament), entertainment of soldiers, portraits of political antiheroes, as well as horrendous scenes from open mass graves – mountains of corpses and their close-ups. This book is turned into an impressive instrument of propaganda by the texts, especially through the captions of the images, which mock and blame the Bolsheviks and Jews for the atrocities.

It is significant that a documentary image becomes an instrument of propaganda due to the caption. This becomes evident when this book is compared to the 1943 German version. There are less photographs in the German issue, but there is more text, offering explanatory essays about the historical context, Soviet occupation, Jews, etc., while the captions of the images are brief – mostly facts about the content of the images. In contrast, the Latvian version is dominated by slogans, textual segments, captions full of pathos and hyperboles. For example, in the German version the caption for one group photo says “Red Front Spanish voluntary soldiers”, while in the Latvian version – “Arrived everyone who cared about the destruction of Latvian country and people, the destruction of land and the destruction of values.” Another image in the German version – “The corpse of a woman in a Riga street”, whereas in the Latvian version – “They committed murders while fleeing the country. A woman murdered by Bolsheviks on the street the day Riga fell.” A crucial difference can also be noticed in the fact that the German edition had only a couple of grotesque photographs of corpses, while the Latvian issue had 15 spreads combined with portraits of the KGB agents, in order to imply their guilt in the crimes depicted. Consequently, the Latvian version is capable of influencing the reader on a more emotional level, giving rise to outrage, fear and hatred, and becoming an effective generator of terror and anti-Semitism. This peak of German collaborationism is an excellent example of how image and text can be manipulated to influence the viewer’s perception and attitude towards certain people, social groups, phenomena and problems.