Interview with Tom Mrazauskas and Michal Iwanowski

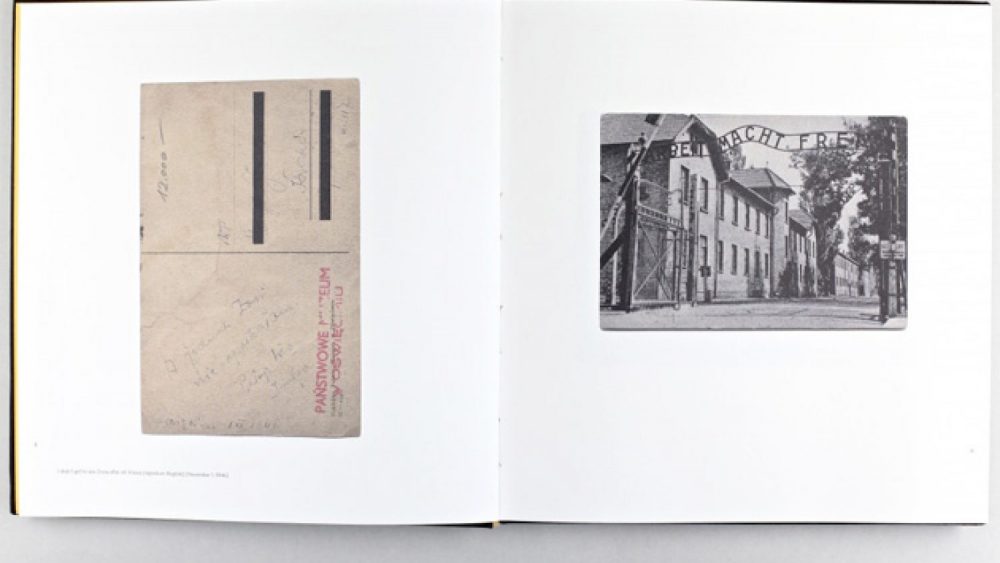

Tom Mrazauskas (1980) is a Lithuanian-born, Berlin-based book designer who has won several awards at international book design competitions and earned a special mention at the Paris Photo – Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award 2014 for the book Photographs for Documents. Most recently, he founded Brave Books, an independent publisher, and in May will be visiting Riga as one of the SELF PUBLISH RIGA dummy competition jury members.

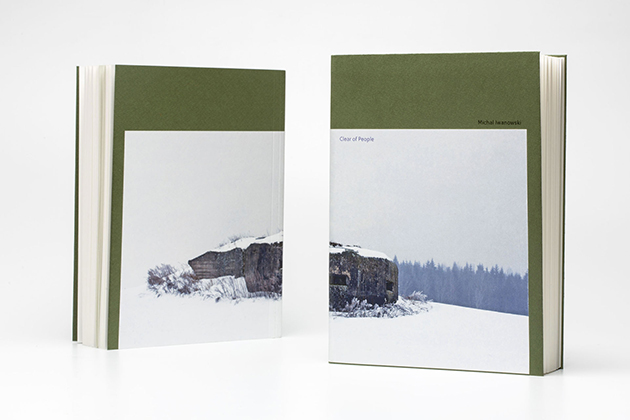

Michal Iwanowski (1977) is a Cardiff-based photographer and a Ffotogallery tutor, whose work explores the relationship between landscape and memory. Together they are working on a photobook Clear of People, which retraces 2200 kilometers of a solitary journey, originally made in 1945 by Iwanowski’s grandfather and uncle escaping from a Russian gulag back to their native Poland. 70 years later Iwanowski returned to Russia with a rough map and notes inherited from his uncle to undertake a similar journey. Just like the brothers did, he stayed clear of people along the way.

The photobook is currently on Kickstarter and can be pre-ordered. There is still a chance to support their Kickstarter campaign until tonight.

Tom, could you tell us more about your new project – Brave Books?

Tom: To encourage people to go for Kickstarter, you must be kind of brave. But I think irony is just in the right place here – to get people involved.

What makes a photobook stand out for you, as there are so many now?

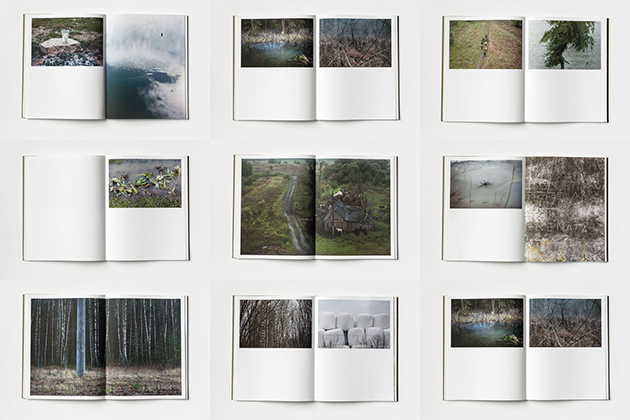

T: Can I say – to make it attractive? Attractive means involving, and involving mostly means some hide and seek games, which you can see all around. In a photo exhibition you have everything on the wall, you walk around, you see the thing, but in photobooks things are hidden sometimes, very nicely hidden.

Michal: The book is a grower, right? You can go back to it and the more you look at it, the more revealing it becomes. It’s not like a pop song – all the material absorbed in one watch. You go back to a book and then you notice the colour of the paper, the documents, the photographs. I think that’s the beauty of it. I remember, when we made the dummy – the more I looked at it, the more I loved it. It’s like looking at your own kids and saying they are the best singers in the class, but I think it’s a great book.

T: If you come back and find some new things, it’s great. Everything has been photographed, everything has been told already, but what we can do is to keep things a bit silent, to go back to simplicity and to add some secret to surprise ourselves again. That’s why it’s so hard to explain what a good photobook is, because it’s all about magic. Good photography is also magic. It is about feelings.

Michal, could you talk more about the project? The historical framework you are using is quite broad, so did you find the easiest way to enter the narrative was by choosing a very personal approach?

M: Yes, absolutely! You hit the nail on the head here. There are so many stories around us you can talk about using photography, but I feel the most comfortable talking about something that I understand very well. I’m not a historian, so I don’t know if I’m in the position to discuss it properly, but I also believe that the best way to approach history is through personal stories because they resonate with so many people, especially in that part of the world. And because I was also very curious about the story of my grandfather and his brother, I thought it would be a great way to honour not only them, but everybody in history who had to escape, run for their lives and had to suffer because of historical shifts.

Rather than preach about history that everybody can read about, if you present it in a way that is touching, you are very likely to achieve something great, I think. I’m not on a mission to change the world, but I have been moved by photographic works like this and I have changed as a person; I feel for the better. And I had people coming to me after exhibitions in Minsk, Belarus, or in Kaunas, Lithuania, with tears in their eyes. They were not crying for me or for my father, they were crying for their own losses, and, I think this is the power of such a micro story within a broader cultural and historical context.

Do you find photography a fitting medium to talk about history or do you think it needs additional tools, like text, for example?

M: Absolutely with text. I don’t see photography as evidence, it’s just an interpretation of a fraction of events. So it’s very dangerous to assume that you can use photography to talk about history. I tried to be very careful not to talk about history as such, but to talk about the phenomenon of having to go, move somewhere, run away – doesn’t matter if its my grandfather or someone from Russia, this is a journey from oppression towards freedom, so I hope that this kind of photography might help meditate on these topics.

Is this project perceived differently in Western and Eastern Europe?

M: Absolutely. I think it’s our embedded Slavic or Baltic sensitivity and our attachment to the land. I recognised the land in Lithuania when I landed for the first time in Kaunas. I felt like I belonged to that land and it was a strange feeling because I had never been there before. So in Eastern Europe, many people who see these photographs recognise everything, while in Britain it’s totally exotic, people think it’s a different world, they cannot relate to it without thinking about history and their own imagination when it comes to that land.

And I think it is tougher to please the Eastern European audience with this project because they know it so well, they understand it and they’ve been there, their grandfathers possibly walked similar distances, while here (in Britain) it is more of novelty, people go – wow, someone walked in the war, it’s easier to use the surprise factor for your benefit. But so far I have showed this work more in the East and I think it reaches a certain place in peoples hearts.

T: That’s the magic I was mentioning, touching people – it’s all about feelings.

M: If you hear a cheap song with strings, a power ballad, you are more likely to get goosebumps or cry than from looking at a photograph. But I myself have cried on occasion while looking at an image and I think that it’s quite amazing to be able to capture something in one image to make people cry for some reason or to be moved. I’m a sentimental Slav (smiles).

Did you actually walk all the way?

M: I did exactly what my grandfather and his brother did. So I walked something near 1000 kilometres, but there was a point when my grandfather couldn’t walk and they decided to jump the trade trains. They would walk for one or two days and catch a train at night, so I did exactly the same, but where they walked, I walked. At one part of the journey I got myself a lady bike, but that was actually much harder work than walking, the bicycle in the forest did not work very well, so I parked it in Kaunas Photography Gallery as a communal bicycle for everybody to use.

How did the experience of walking and avoiding people influence the work?

M: I don’t know any better way to photograph than to take your camera and walk. It gets physical because when you walk, you achieve a certain rhythm, it’s like a metronome moves with your feet and you get in tune with the sounds, you even start hearing things from inside your body because it’s so boring. You walk for eight hours and nothing happens. Let’s face it – the forest is wonderful, but for eight hours? You’ve seen it all. But the wonderful thing is that at some point because of the boredom I will find anything that’s different in the landscape super refreshing. Suddenly I would see from far away that there is a scull of a dead cow hidden in the tree, which normally I would pay no attention to.

I don’t want to do any other way of photographing, I just want to walk and photograph because that’s such a pleasant, rewarding and quiet process (smiles). I would recommend everyone to walk at least a thousand kilometres in their life. You get to see things that you normally wouldn’t think are interesting at all and because I avoided people there was nobody to talk to.

How long did it take you?

M: About nine weeks all together. I did it in instalments.

I was reading in one of your interviews that you were planning to show the pictures to your uncle. Have you shown them to him and what did he say?

M: I managed to go and see him before he died, but without the book dummy yet. It was just a few printed photographs I sent him. So we never had a chance to talk about this journey after I completed it, but I went to see his wife. She is the last woman standing, really nice and clever and very proud of what he did. I was worried because it is a different generation who understand different visuals, but she actually appreciated the stillness of photographs. That was great. But my father and my uncle have died now, so this is a post mortem tribute to them. But my uncle was very moved that somebody cared enough to talk about it – not to praise him, but like he said, it is important for other people to know that these things happened, maybe for better decisions in the future. History repeats itself, but you have to try to make some changes.

So when is the book coming out?

T: We plan to print it in May and to have it in everyone’s hands in June. Just to add to what Michal was saying about people’s reactions, on my last trip I had two sets of printouts, a luggage bag filled just with printed sheets. I went through the airport security in Berlin and got asked what’s in the bag. Sheets of paper? Yeah, sheets, do you want to see? I took it out, he flipped through and said – oh, interesting. Our first fan.

M: And interestingly enough in the airport – a place of transition and migration. That’s a very good sign.

Tom, what are your future plans as a publisher?

T: Everything is top secret. Also this project I was developing is top secret. I learned this from a German publisher – not to talk too much about what you are doing, but to show what you did, because that’s most important.

Are you planning to concentrate on projects from the Baltics or ones that are made in this region or doesn’t it matter?

T: I concentrate on work that looks the best in book form, it can come from wherever. I think a lot of photobooks are just collections of images, but don’t work as a book, not making that magic. So my ambition is to make little magic books. Not 500 pages, 120 is enough to make magic.