Interview with Anders Petersen

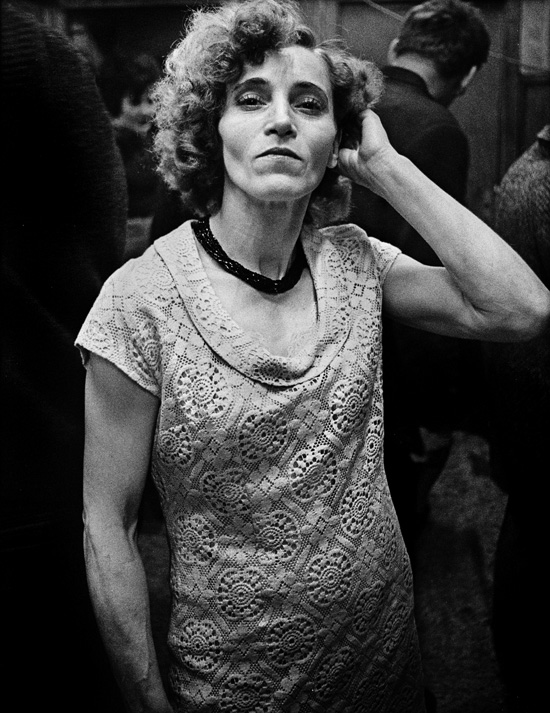

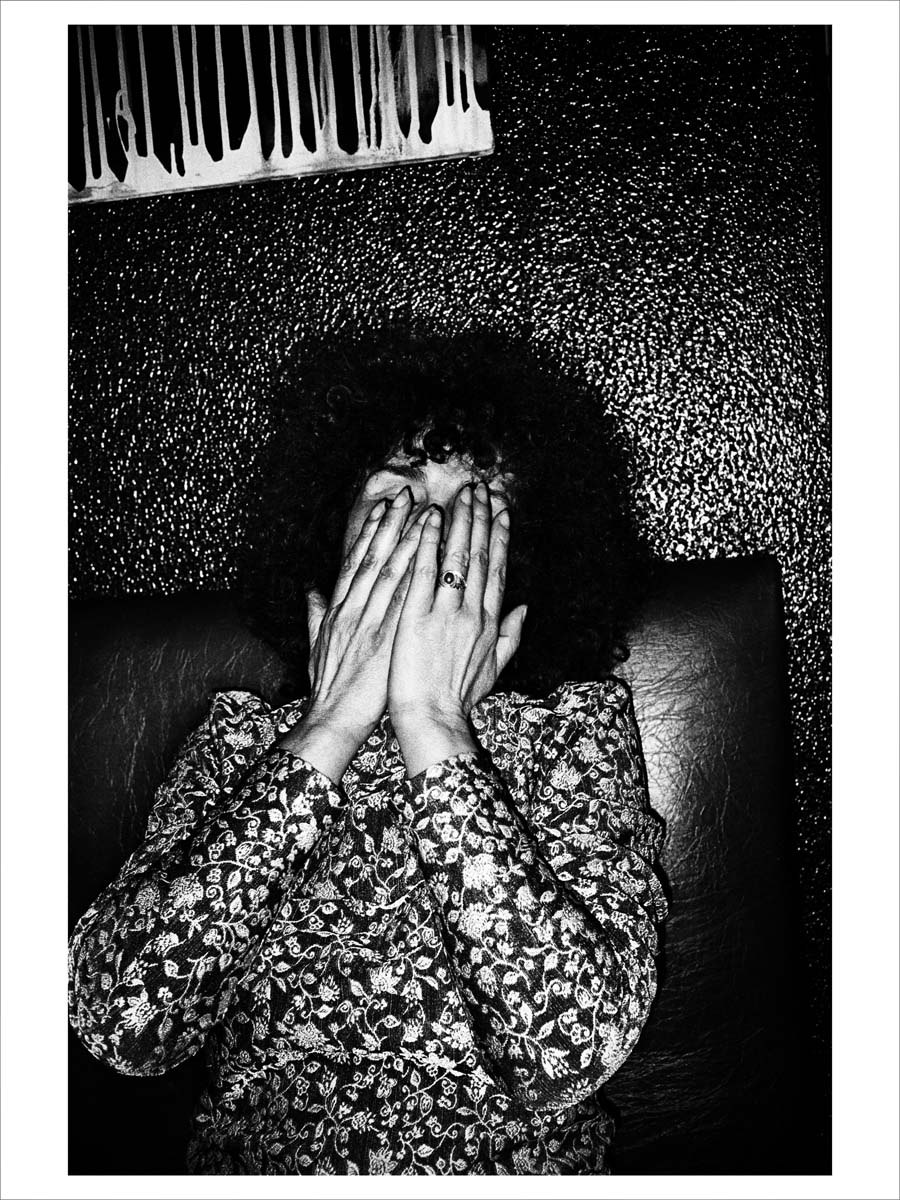

The Swedish photographer and a living legend Anders Petersen (1944) came to Riga last week in order to do a portfolio review, as well as the artist’s talk that attracted a lot of attention from the local public, as the hall where his presentation took place was packed. Known for his ability to find a common language with complete strangers, he also comes to the interview making you feel special. “I am honoured to meet you,” he says and later lays out dozens of his own images on the table, just like young photographers do for him at portfolio reviews. “The stuff I do is a kind of private documentary photography.”

You must be a man that always carries a camera with you…

Yes (showing me his camera). Contax T3, 35 mm lens, very good lens, sharp in the corners. I made 2 meters prints and they were sharp in the corners. (The camera is loaded with Kodak TX 400). Always 400 ISO. All my work in the past 12 years has been done with this camera. I have used another one, too. It is Ricoh GR1s, with 28 mm lens, it’s more wide [lens], but I prefer 35 mm lens.

What is it that after all these years of photographing people still keeps you being interested in people?

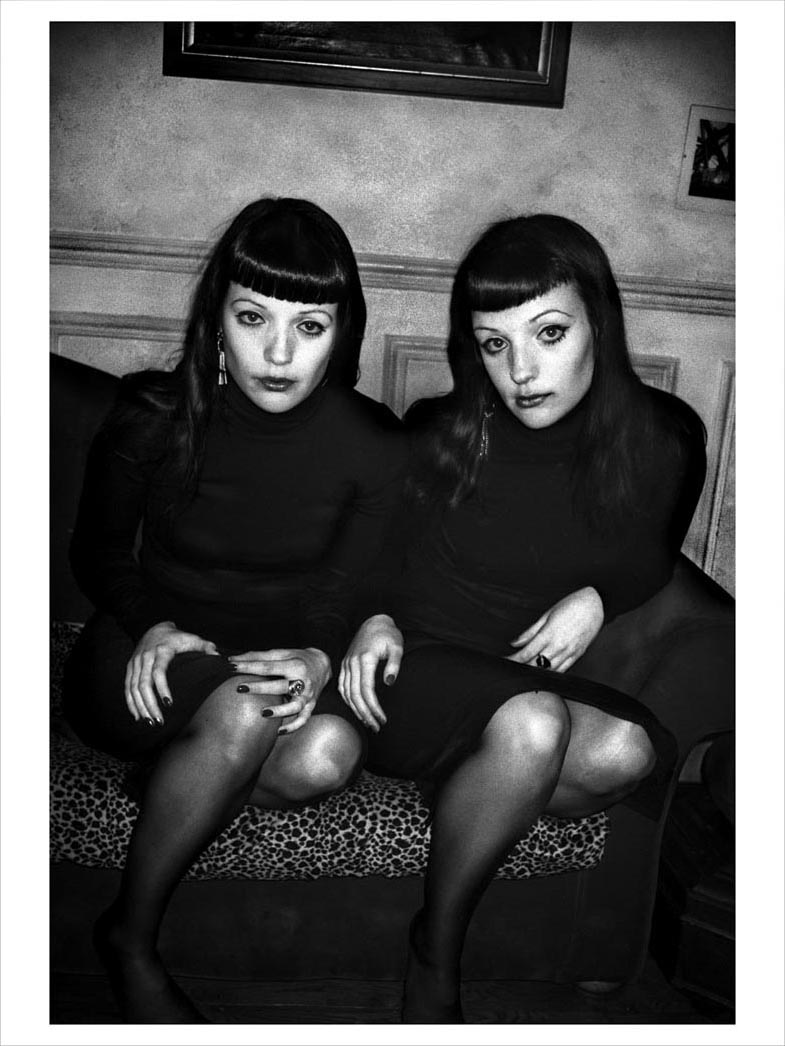

I am a maniac. I really continue asking questions mostly about myself. Sounds egotistic and probably it is. I am asking myself – who am I and why. And then I am looking for people and other beings to whom I identity myself – women, men, dogs, cats… I think it’s all about identification with people that I belong to. On the other hand, I am not sure at all, so I keep going. In a way it’s ok not to be sure and it’s ok not being so brave. I’m quite afraid of everything. I think I’m a type of photographer with longing for companionship, friends, communications, trying to understand myself and other people. And I think I understand myself through other people, more and more. And I understand another thing… I know it’s a basic fact, that we are all humans after all. It’s a big family. But on the other hand, it is true… If you go back to basics, you are relative to all other people in the world and it doesn’t matter whether you are in Japan, Paris or Riga. I am trying to look for what is making you feel closer to other people. I am not looking for what is drawing us apart – I want to be close. I don’t look for differences despite I know we have different cultures, religion, but anyway we are all the same. And that is the basic, kind of a primitive platform, my way of photographing people.

Is that your philosophy of what photography stands for you?

For me, with all the faults you can find, it is a kind of philosophy that I can find inside me. It’s not a religion although it sounds like one, perhaps. Photography is not about photography, but for me, it is meeting people, other people and trying to understand myself. We are not just one man, there is more in you than just a person I see sitting in front of me, you have more personalities inside you and it is a challenge for me to find out… and take pictures.

Do you often look back at the work you’ve done in the past?

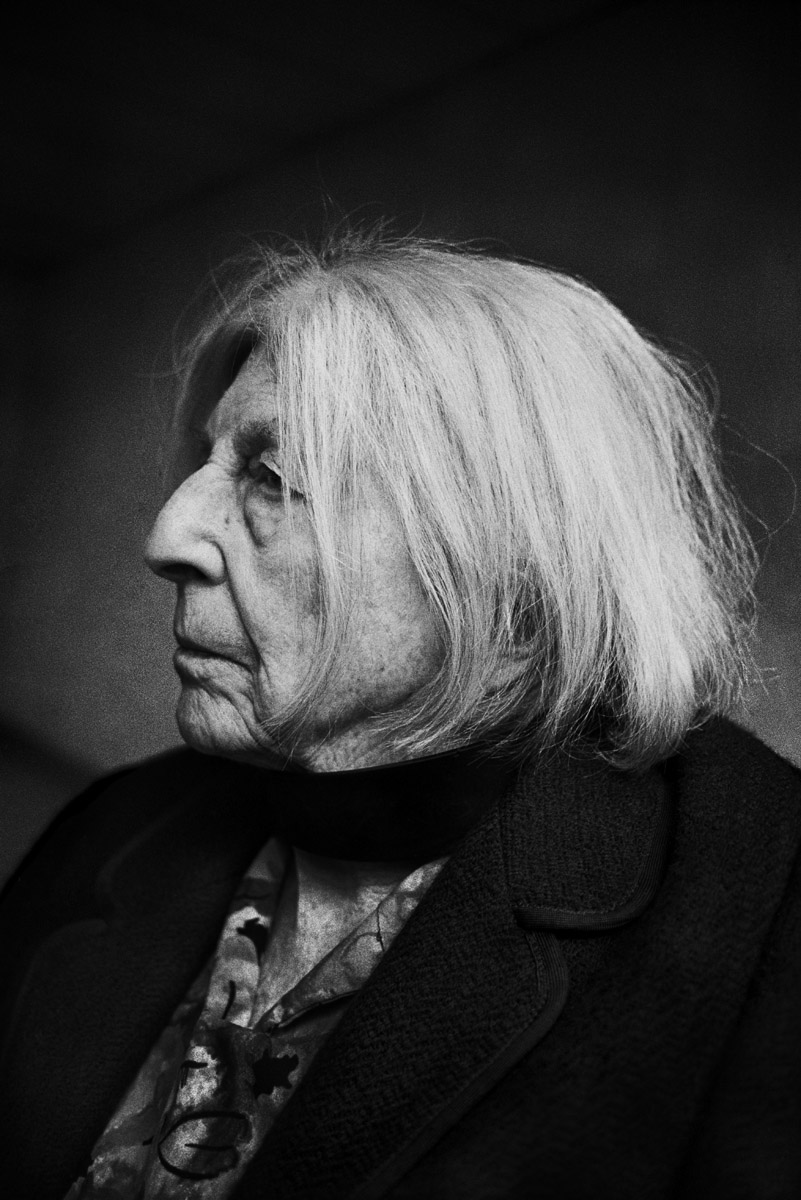

No, I try to avoid it. I try to live in today, not in the future or past. I try to be as much as possible today. But, of course, you think what have you been doing and all the people you have met, especially now, when I will have a retrospective at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. And then I go through the negatives taken 40 years ago and I start asking myself what has happened to all those people I have met, are they alive, are they happy. And this is a big trip and you feel the life passes by in a glance.

Isn’t it true that with the age and experience you become also more conscious and aware of what you are doing and it makes it harder to photograph, to maintain that innocent eye?

You are so right, so right… My dream is that if you go out in the streets where you were born you see the streets like for the first time in your life even though you have been living there for 60 years. That is my dream, but of course it’s not like that. So, what you have to do is to be aware mentally of all those experiences, and knowledge is a rather heavy rucksack and it’s not good for being creative. So, what you can do is in a mental way you have to go down to zero, to clean yourself as much as possible, I know it’s impossible. When I was working in prison for 3 years, there was a very famous criminal Jaki. After a while I got into his cell and asked him, why are you so famous, how it comes you are so good. Because everybody was talking about him. And he said, it is simple, you have to imagine a life like a pyramid and you have to reach the top of it. And it’s not just about being criminal, it’s also much about photography. At the bottom of the pyramid there’s safety, you have your family, friends, women, people you love, but you can’t do any masterpieces there, you have to be clear. In order to go to the top of the pyramid, you have to get rid of them. And it is very much a mental process, as Jaki said it was like peeling yourself from it. And when you come to the top, it’s like a fever. Once you are there, the only thing that matters is what you have to do, and nothing else matters. Then you are dangerous and then you attack. When I heard it from this criminal, I thought this is also true about photography. How to catch momentum… you have to be very fast, ruthless when you crop the situation you are in. You are not supposed to be into the situation with both your feet, but one foot outside, in order to attain the best result of the situation.

I guess the problem with many photographers is that they don’t get close enough to the situation or subject. Your pictures certainly have this feeling of intimacy. Can you give some tips how to achieve that?

That is a typical problem. The best advice I can give is to understand not so much by brain but by heart that you belong to the same family as the one in front of you that you want to photograph. And you will see that your body language and approach will be different, and also they will feel it. It will be like meeting a friend.

I have heard you saying in an interview that black and white has more colours than colour photography…

I think so because in black and white you are not caught by the colours, you have your own fantasy and experiences and they are all in colours. So unintentionally you add colours to the black and white photograph.

Has it been important for you to retain a certain photographic style in all your work?

That is a red line from my first work until what I am doing today, you are right. But I don’t know really what to say about it. It’s not really a style, for me it is an approach. It is more distinct for me, it doesn’t work that much with anecdotes and atmospheres. It works more with light and shadows. I’m interested in a distinct, sharp attack. That is not explaining anything, that has no answers, but has many questions. And the more questions and longings I can find in one cut, the better. If you are curious and patient enough, it brings a lot. You can open the door and the camera is like a key. I am not so much for brain photography, idea-based photography, even though we always need some idea, some fundament to stand on it. I am more of that style of photographer, who is more intuitive, using my stomach and heart. I want my cut to be organic, I want an organic result. This is important for me.

The more you talk about photography, the less it is about photography. It’s more about the conditions of life, people and it is more interesting than talking about technics, lenses and cameras. You are not supposed to be a slave of mechanical tools, they are supposed to help you and be as small and as unimportant as possible not to disturb the communication. That is what I feel when I shoot my pictures.

What is the project you are working at now?

Now I am working with my diary pictures. That’s one of the reasons I have a camera on me and I take pictures more or less everyday. Also I will put together a volume of book with the pictures that my teacher Christer Strömholm liked. What he did, he put his initial C on the images he liked. So I am trying to collect them and make a little book that I will call C. And then I will publish a book about Soho in London, I was there last June in a residency. And this June I will have a residency in Rome.

What has lately impressed you?

Daido Moriyama and the book I saw in Paris Photo Sunflower. You should have it!

When did you start doing talks and teaching?

It has always been part of my work. I started to teach when I was still a student myself. I needed money because I wanted to travel so much, and I needed money for materials. And then I started to show my pictures but I never sold any pictures at the beginning. Nowadays I sell. When I make exhibitions, I sell to collectors. It’s getting more popular with collectors.

Do you collect photographs yourself?

Yes, I collect my friends [photographs]. I have many nice pictures. I have to exhibit them before I die. It’s nice but a little bit scary, very special taste, it kind of describes me, like a self-portrait.

Do you still print your own work in a darkroom?

Yes. My standard is always 24×30 cm and then I make bigger if someone wants. In New York I had photos all over the walls like wallpapers.

Yesterday you were reviewing some young Latvian photographers. What are your impressions?

They are passionate people; they want more influences. The hunger was obvious, the longing for more stimulus. That was moving, very nice to see. Some of them were really creative; the women were very creative. They were on different levels, but good levels. Of course, there were some warnings, that they have a tendency to jump into clichés, but, of course, we all have. That’s also why it is important to have the right stimulus, perhaps to go abroad, to go to festivals, such as Arles, Photo Espana.

It is important to be able to show your work in festivals. I was showing my series Café Lehmitz in Arles photofestival in 1977 and that is where I was also able to make a solo show. I got the place of Josef Koudelka because his images were stopped at the border. And after that immediately there were two publishing houses coming and that is how I got my first books published. And I was a lucky guy, thanks to the festival, Josef Koudelka or the Czechoslovakian border guards (laughs).