Interview with Christopher Anderson

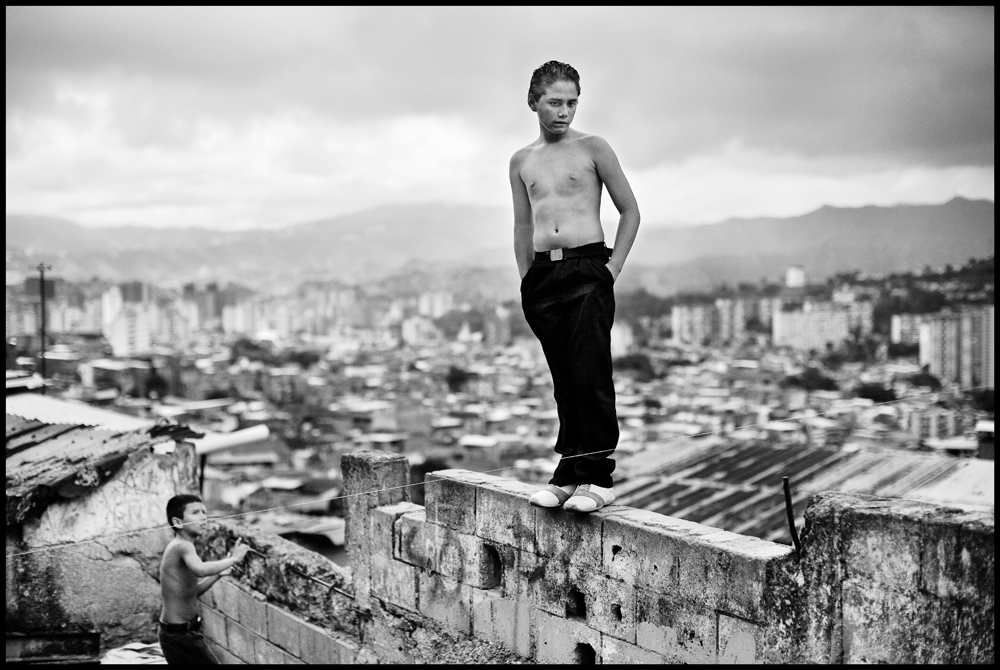

Christopher Anderson (1970) was born in Canada and grew up in west Texas, where his father was a preacher. His life in photography began in the photo lab of the Dallas Morning News where he learned to develop film and print pictures. In 1993, Christopher was hired as a staff photographer for a small Colorado newspaper. Never comfortable with the idea of working as an employee, he left the newspaper in 1995 and began doing freelance assignments. In 1996, he became a contract photographer for the U.S. News and World Report where he began documenting social issues such as the effects of Russia’s economic crisis, the situation of Afghan refugees in Pakistan and, more recently, the election of Evo Morales in Bolivia. He first gained recognition for his pictures in 1999 when he boarded a handmade, wooden boat with Haitian refugees trying to sail to America. The boat, named the Believe In God, sank in the Caribbean. In 2000 the images from that journey would receive the Robert Capa Gold Medal. They would also mark the emergence of an emotionally charged style that he refers to as “experiential documentary” and has come to characterize his work since. Christopher Anderson is a member of Magnum Photos and is currently the New York Magazine’s first ever photographer-in-residence.

How did your fascination with photography begin?

By accident! I never made a decision that I would be a photographer by profession. I was playing around with photography but just as a hobby, as an interest. I’m not formally trained in photography, art or journalism but I sort of fell backwards into photography as a profession. It wasn’t actually until I was a professional photographer that it crossed my mind. Once in that setting, I worked hard trying to learn my craft but there was a period of many years when I wasn’t consciously choosing what kind of photography I was going to do. I was only reacting to what was coming to me. Somehow through that passive path I was one day called a war photographer which is not a turn that I ever accepted. For me, I was only photographing. It wasn’t until 10 years of being a professional photographer that I actually started asking myself some very basic questions like “what is a picture?”, “why do I photograph?”, “what is the point of photography?”. That’s where my work started to rapidly evolve into different things, I guess now people think of me as a former war photographer who is now doing these personal projects. I reinvented myself! But even that wasn’t conscious, it was my curiosity taking me in what seemed to be an obvious direction.

What about Magnum then? Did you dream about becoming its member?

Well, as a professional photographer, you’re aware of these things. It still didn’t cross my mind, it wasn’t an ambition of mine until about the time I did it. Mostly for two reasons, first – I was at the Agency VII at the time and second – I probably didn’t dream that it was possible. At the same time, I had immediate close friends who were already inside Magnum – Alex Majoli, Thomas Dworzak, Paolo Pellegrin – these are people whom I’ve grown up with professionally and they are really my best friends. That’s when I was sure I wanted to be part of it. Of course, also because of its history, what Magnum represents but really, more than anything, to be with my friends. People will read that and think it’s a total bullshit but it is true!

What does it mean now, to be in?

It’s my community. It’s my home and my family. The same people are still my close friends. I shared the history with them before Magnum and now I also have a connection outside Magnum.

How does a working day at Magnum look?

Which one? Every single one is different, no two are the same. Right now I’m a photographer-in-residence at the New York Magazine, now my work days are mostly in New York which is fantastic because after years and years of travelling I can finally stay home and be with my family. It’s to wake up every day and think about photographing the city. It’s the first time for me to photograph the United States in a serious way and so close to home. Some days I’m photographing, some days I’m editing, some days I’m also doing administrative work. It’s a business.

Are the goals of Magnum today the same as the day when the agency was created?

I think that the goals haven’t changed at all. To exist as a community of photographers and to provide a certain strength in that community that could both provide a photographer a means to defend their work and to reach the audience. Magnum was founded in the idea in documenting and engaging in the world. What has changed are the ways of doing that. Some markets have changed, some have disappeared, the way to make the living from it has changed, in some ways the language how to do it has changed, the visual conceits or constructs that a documentary photographer might choose to use but I think that the misconception is that there is this young generation of art photographers at Magnum. It’s a misconception because that sort of dialogue at Magnum has always existed – to balance those who have always worked more as photojournalists and those who work more in art photography. The language simply looks a little bit different visually now. People are surprised that Magnum isn’t a museum that is collecting dust. It’s a vibrant, dynamic, living, breathing place that brings in new blood and is trying to find new ways how to engage with the world and reach its audience.

Do you see any tendencies in the photography now?

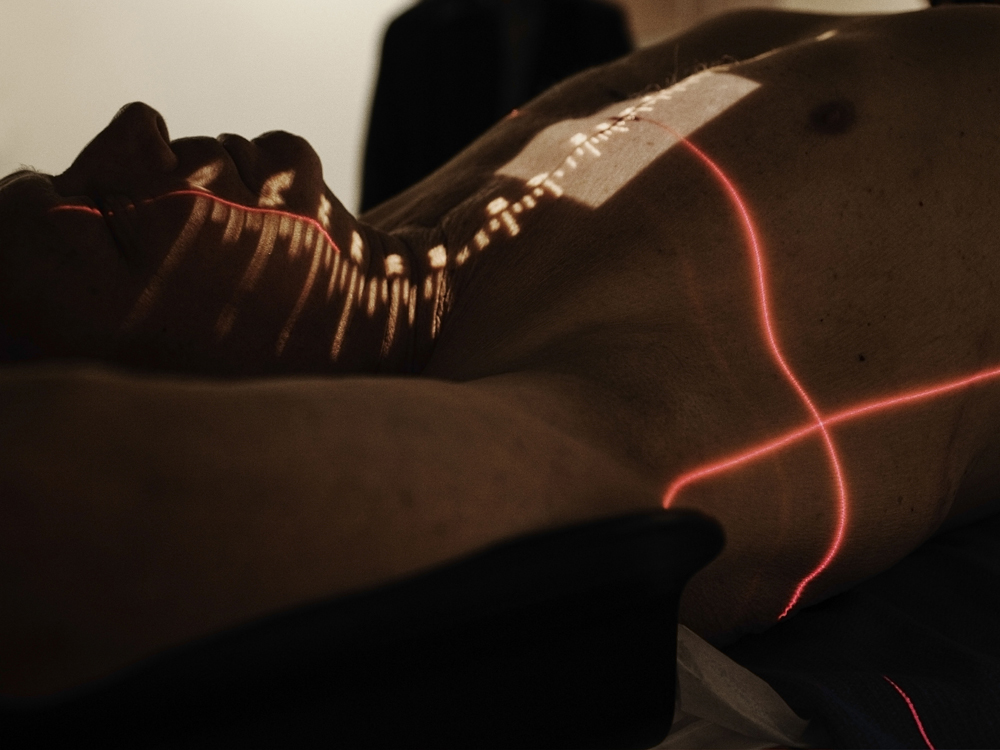

You always recognize little swings in current modalities or fashions. I see a lot of young photographers now coming to show me their personal projects of their families or their personal life, kind of a personal documentary which I think has a much to do with the disappearance of the traditional markets. To put it in easier way, as there are not enough of assignments, people are staying home and photographing their families (laughs). In my generation, the conversation about the division between documentary and art photography became meaningless. The photojournalism before was somehow objective and based on facts. Now, we do know that photography lies, we know that it is not objective. Now it’s more about the truth and not the facts, and those two things are not the same. I don’t believe in existence of facts or objectivity but I do believe in truth and in truth in subjectivity. These perceptions have changed not only among the photographers but in the public also. It changes the approaches. There was a period in the evolution of photography when we looked at the picture and it had a certain value just because of the difficulty of making the picture. Technical difficulties – cameras that were a little bit awkward to operate with, exposing film correctly etc., but now with the digital, none of that matters anymore – low light or exposure is no longer a problem and we become visually so sophisticated that it is boring. My generation and generations after me, young generations, are less and less interested in fact of perfect compositions and action of making a perfect image; they are more interested in just a raw emotionality of it. That’s how I see now and that’s where older generations have hard time. Photography becomes more simple and more direct. Since everybody has a cell phone with a camera and they are taking pictures, everyone has become a photographer. Some are using this snapshot quality in good photography partly because it is language of today that everyone understands. And it’s hard for a person who is not a photographer to relate to this complex photography.

How do you orientate in this mass of photographs?

Sometimes I get overwhelmed by the flood of imagery and not just bad imagery because there are, of course, lot of bad images. How can my images find an audience through all that noise? The only answer I can find, maybe it is about authenticity. If there is something that someone connects with, that’s because there is not just good and bad photography but because there is some authentic quality to it. It’s a picture that is distinctly mine and maybe that has some value above being classified as good or bad.

We tend to work in series of images nowadays. What about the power of one photograph?

For a long time, not only we got the news of what was happening in the world from the photographs but the world was also a bigger place. National Geographic was an important magazine because that was how people traveled to other corners of the globe, by looking at these images. Now everyone has been everywhere. We are not so fascinated with the exotic anymore because there isn’t exotic anymore. Even if the world has changed I still believe in the power of photography. Maybe I just have a wishful thinking because I’m a photographer.

Is there a photograph or a photographer, a mentor that has influenced you?

My mentor was James Nachtwey and I owe a lot to him. But there are others that have been important as Gilles Peress, a photographer Jose Azel. Then I have huge influences too that I think are quite obvious when you look at my work and I don’t deny them. My generation grew up, for example, with the music that was made from a sampling of other music and it’s not just an influence anymore, the sampling is the point. I kind of feel the same about my images. My work Son, for instance, you can’t escape the influences of American colour photography – William Eggleston. It’s also the fact that I grew up in America, I work here and I speak English, so why should I reinvent the English language? People always say this but it’s true, I’m influenced not only by photography but by music and literature, cinema. I’m interested in so many different types of photography. In my work Capitolio there are pictures that are chosen to be there not just as references but homages to particular photographers.

What is the most rewarding thing in your work?

Providing for my family right now. It’s rewarding for me to have a sense that people get what it is that I’m doing. Not because of the notion of loving the success but to finding a comfort of knowing if someone connects with the work that maybe you’re not wasting your time. To feel that you’ve communicated successfully.