Interview with Michela Palermo

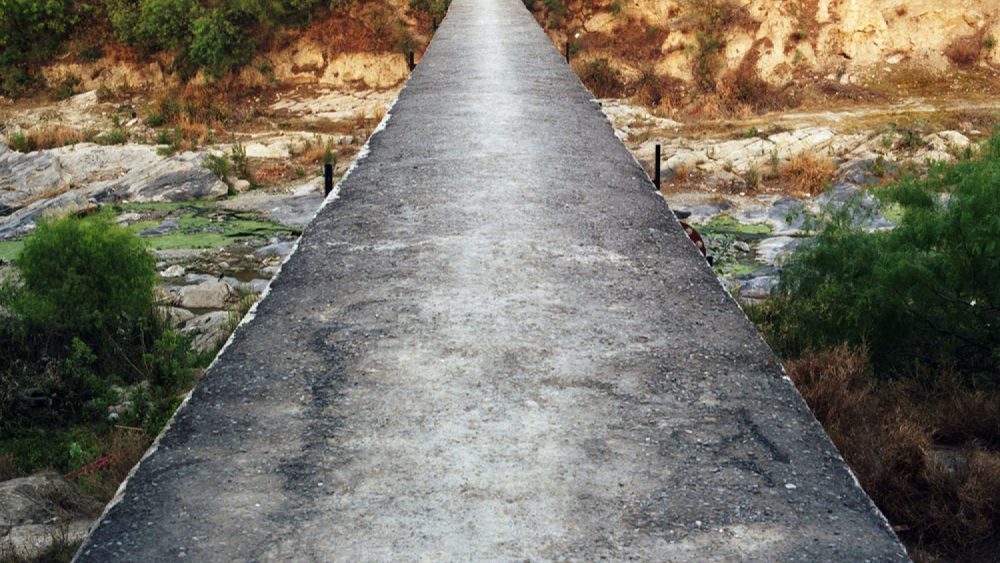

Italian photographer Michela Palermo (1980) explores Castel Volturno, which is one of the poorest areas of the Campania region in Italy and also one that has been most affected by the mafia. The area has been devastated through decades of real estate affairs that have turned natural forests into wastelands with an unclear status. Since 1980 the region has been experiencing a strong influx of immigrants from Africa. Today, South of Italy has the highest rate of foreign citizens.

After obtaining a degree in political sciences at the University of Bologna (Italy) Michela Palermo graduated from the Full Time General Studies Programme at the International Centre of Photography in New York. Since she started to focus on photography, Michela has created three projects examining places around her. At the moment Michela Palermo works as an editorial photographer, represented by the ONOFF Pictures Agency. She is also one of the artists from the Middle Town project organized by the ISSP.

It is interesting that you have a degree in political sciences. What made you turn to photography?

Before to study photography I accomplished my studies in political sciences with a final thesis about women’s rights in multicultural societies. During my research through gender studies I realized how meaningful the process of representation in identity construction is and how powerful photography can be in conveying different meanings and information to the viewers. So I started to reflect about the role of images and the use of them, and as an image maker I question my role and my works.

You photograph immigrants from Africa, the second generation who were born in Castel Volturno. How do they feel about living in Italy and how is it reflected on their identity?

Mainly they are just left alone. There is lack of recognition of their diversity and they are not supported in the process of integration by the institutions. But I think, ironically, this emptiness comes from a sort of hybridisation that the second generation has to experience in terms of their origins and culture, on the one hand, and Italian society, on the other hand.

I think it’s important to realise that nowadays the construction of identity is not defined as a sense of belonging to a national community. These immigrants speak more than one language and they have a different sense of geography. It should be seen as positive by the Italian system as a host society. That’s why I strongly believe they can represent a sort of counterpoint, bringing new energies to the country. But unfortunately they are not supported by the system, and the real risk is the fact that they are hushed up in a society which makes them invisible.

With this series you have been also participating the Middle Town project which is organized by the ISSP. How did you decide to take part in it?

I thought Castel Volturno project could fit well in the Middle Town concept. Castel Volturno, as I tried to depict it, has nothing spectacular. Usually this place is mentioned regarding illegal immigrants or other issues related to camorra (mafia), but it is more or less impossible to hear about one of the biggest black communities in Italy and its daily life. The second generation is almost invisible and they are hardly involved in the assimilation process. I was very excited to share this in a collective project where we were supposed to explore different areas in Europe.

It was a beautiful experience because each of us developed an idea of the middle town in a different way (photographically, as well as conceptually), and it was very helpful for me to reflect on my project mirroring the works of others.

You have implemented two more projects My Broken World and As I Was Following You, which mostly reflect your personal quests and interests about places around you. How would you describe the uniqueness about each of them?

Chronologically As I Was Following You was my first project. I started it when I was student of photography in New York: at that time I didn’t have much clues for my photography, and I think it was my first attempt to explore my personal emotions through images.

Then I came back to Italy and it was almost natural to direct my gaze to the places where I grew up. My Broken World is my personal point of view on the aftermath in Irpinia 30 years after the earthquake.

I was born a few months before the earthquake and I spent my childhood in Irpinia during the process of reconstruction of the area. When I was a child, everything was broken. Despite this fact, I grew up fascinated by the beauty of vulnerability, and I guess this aspect is evident in my approach.

Generally, I consider the earthquake of 1980 in Irpinia as a switch from a rural to post-industrial world, a phenomenon that’s been affecting different parts of Italy in the last years and has changed the face of the entire country. Broken stands for this interruption, for something lost behind, for the desire to carry on.

Since this project I have been shooting colour and I feel committed to documentary photography, using my theoretical background to find stories I feel interested in. I also keep shooting black and white, like visual notes of my experiences, and I feel these two different approaches are interconnected.

In one way or another, I feel strongly related to the images I have produced, with the subjects I have encountered. There is something about the gesture and the texture of these pictures that I consider a way to make me speak about what matters to me.

You have been represented by the ONOFF Picture agency. What influence does it have on your daily life and how it helps you to develop as a photographer?

The ONOFF Picture is a young Italian agency. It was founded collectively in 2009 by a group of young Italian photographers and I had a chance to join them almost two years ago.

I think the most important part of being in the ONOFF Picture is the opportunity to share my workflow in a small group of young photographers. Often we confront each other during the group meetings or over Skype when we discuss our projects, experiences, networks.

We have people in the agency that coordinate us, worry about our progress and support us in our research, not to mention the simple but also important aspect of distributing and selling our works to magazines.

What is the main difference between working abroad and in your homeland?

I usually focus on projects regarding my homeland. I need to feel a deep connection to understand and to process what I see through my camera. However, I also learned how interesting it is to jump in unknown projects and places and use my way to formulate my photography path.

In May 2009 you were selected for a workshop on a dummy book with Magnum photographer Martin Parr. What was it like and what was most inspiring in this opportunity?

It was a very nice opportunity, one of my first experiences with the book publishing process. They allowed us to meet some important publishers and designers and we were showing our dummies and offering our ideas.

I believe this kind of experience is very useful to create a social network.

What are your plans in photography besides finishing Castel Volturno project?

I will complete the project and will try to publish it on my own. Also, I want to organise an exhibition. I think you can have a totally different experience through photo installation, and I would be very happy to have a chance to display the project on the wall and work on the layout. I have some new ideas on my mind and I still want to work in Italy.