Interview with Aaron Schuman

This year’s Krakow Photomonth is curated by Aaron Schuman – an American photographer, writer, lecturer, curator, the founder and editor of SeeSaw Magazine, currently based in the United Kingdom. His extensive CV includes contributions to Aperture, FOAM, TIME, Photoworks, ArtReview, Hotshoe and The British Journal of Photography among others, a number of texts in recently published books including Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals (Carnegie Museum/ Prestel, 2014) Photocinema: The Creative Edges of Photography and Film (Intellect, 2013) Pieter Hugo: This Must Be the Place (Prestel, 2012), Photographs Not Taken (Daylight, 2012), Hijacked 3 (Big City Press, 2012) and shows, curated in London and Houston. In 2010 he visited Latvia to lead the workshop An Aesthetics of Nostalgia and kim? hosted his exhibition Once Upon a Time in the West.

Shortly before the opening of the exhibition of his newest work FOLK: A Personal Ethnography, part of Krakow Photomonth, Schuman talked about the ideas behind organising the festival, what it means to be a photographer with capital letters today, about teaching photography and his own work.

Krakow Photomonth is running from May 15 to June 15 in exhibition spaces all across the city.

This year, the festival’s main theme is Re:Search. Could you talk a bit about the idea behind it?

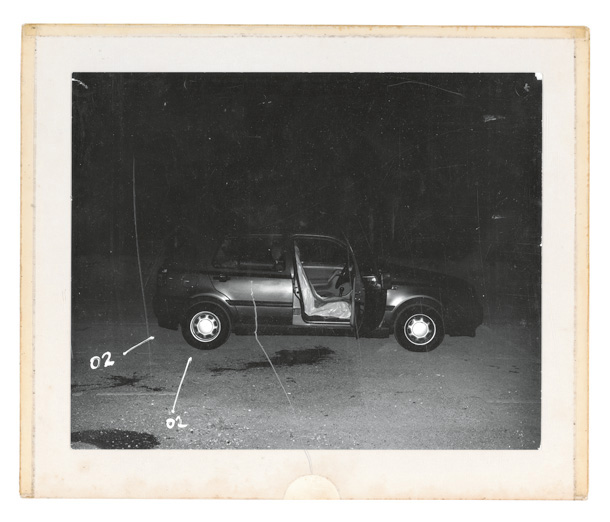

It started off with the fact that a lot of photographers I was interested in were dealing with the process of making their work as well as the final output. Somebody like Jason (Jason Fulford – E.G.) whose work is not only about pictures, but also about the process of making them, editing, embedding them, making events. Clare Strand is starting to build more sculptural pieces and incorporating her research material into her practice. Also Taryn Simon, who is making work about the place where photographers throughout history have gone to look for pictures (New York Public Library – E.G.). So I was really interested in this idea of looking at the process of making pictures and the researching side of photography, and how that’s becoming more explicit and important in contemporary practice. I was also interested in research in a more traditional sense, of an image as evidence. You can’t even name a scientific or social scientific field that doesn’t involve photography – whether it’s physics, biology, anthropology or economics, all of these disciplines use photography as a form of research. So I was interested in a relationship between these two things, photography as something that leads to knowledge, helps you search for knowledge and also something that contains knowledge. I also teach photography, and both for students and also for professors, the word “research” has almost become something that creates a feeling of dread. If you are a teacher and you say to your students: “You need to go and do some more research!”, you can see how they sort of sink and think: “Oh no, now I have to go and do something really boring. I have to go to look at books or I have to think about something too hard.” Also, professors are under a lot of pressure from universities to produce “research”. That puts the same feeling of dread in their hearts, because it is very difficult for them to say: “Well, I made these photographs and that’s my research”. So I was also trying to turn that word into something positive rather than negative. That research can be fun, playful and curious. You know, it can be looking at statistics, reading books and doing lots of historical evaluation, I think it’s really important, but it can also be having this conversation, it can be walking to your friend’s apartment at 2 o’clock in the morning, dreaming. The idea that your whole life is research, I think, is an important one, especially for photographers, because that’s what we do.

I really like that the evidence of research is incorporated in the exhibitions. There are notes, e-mails and books, not just finished final pieces.

That’s what I really wanted to shine the light on. Today everybody is a photographer, and I think now to be a photographer with a capital P, is more than just taking pictures – it is thinking about photography, it is trying to understand how the medium works, how other people have used it, how it can inform you about certain things, how it can inspire you. Every photographer that I know, respect and really appreciate seems to have that tendency. And I think they always had, I’m not saying this is a new approach, but in past that research has been hidden quite often. They don’t show you their contact sheets, they show you their final prints. But today they are showing you their contact sheets, they show you the photography books that inspired them, because it is a really important part of their final work. That’s what defines somebody who is taking the medium seriously and passionately. It’s not just about pulling your camera out. Similar to writing. We can all write, we all have pens and paper, we can all write a poem if we want to, an article or a novel and some people are better at that than others, some people take it much more seriously. I could write a poem right now and it would be a really shitty poem, but another person who reads a lot of poetry, who thinks about poetry, who looks at the history of poetry, could be capable of making really good poetry. Everybody can make a picture, but some people are really good at it and treat it with a sense of importance and urgency, photography is an integral part of their life. And other people want to show their friends that they are having a nice meal. And I’m OK with that. But I don’t think I want to do an exhibition with people’s facebook photos of their lunch.

I read your interview on LensCulture and liked the comparison between photography and writing. Everyone can take a good picture, everyone can write a great sentence, but not everyone can make a great book.

I think it’s really important, and especially because I’m teaching photography. People still often have a misunderstanding about photography – that it’s a technique, a practical skill and needs to be taught in that way. There is a lot of pressure for photography departments in universities to almost guarantee their students – you will have employable skills at the end of this, you will get a job, you will have expertise in the field. I think it should be treated more like a literature or philosophy degree. Of people who study philosophy – one of them might become a philosopher, the others go off and do other things, but nobody questions a philosophy department and asks – how are you giving your students employability skills? It’s just respected as a field of study. It means that there are a lot of people in the world who are intelligent, engaged, informed and interested in that subject. That’s how I see it.

Maybe it’s because commercial photography asks for a lot of skill and these two fields get mixed up?

Yeah, but at the end of the day with the technology and how it’s developed in the course of the last 15 years, I don’t think commercial photography takes that much technical skill. I mean, the machines are good, it’s hard to make a bad picture. If you have enough money, get the right camera, the right lights, the right location – I think you can teach somebody in a week how to operate the equipment and make a technically proficient, good image. You can spend months learning Photoshop or you can open it up and teach yourself the basics through youtube clips in a day or two. Maybe a hundred years ago making a technically proficient photograph was a real challenge, you had to get the exposure exactly right, you had only one or two chances, but today that doesn’t seem like a big challenge to me. I think I could give my nine-year-old son a camera and after a day he could probably get a photograph that would be technically good (not to say that it would be a great photograph).

How about the artists you chose for the Krakow Photomonth? Did you start to think about the idea of research and they came into your mind, or were they people you really wanted to work with from the beginning?

I started off with artists I really wanted to work with and bodies of work I wanted to show to people, that’s where the idea stemmed from. I knew that David Campany was making a book about Walker Evans’ magazine work, I’m really excited about what Clare Strand has been doing in the last years. As soon as I saw the New Roman gallery, Jason Fulford immediately came to mind. And then I started to think about how I’m going to justify bringing all these things together. With SeeSaw Magazine it’s similar . None of the issues have any theme, it’s just stuff I like and I never make links to connect why all these people are in the same magazine. But obviously for the festival there was a need to justify why they should be linked together and this link for me was the notion of research and searching for knowledge.

Did you have a lot of freedom curating the festival?

Conceptually I did have a lot of freedom. There were people that I would like to have included, but there wasn’t the space or when I presented the project to the festival, maybe they wanted something slightly different, but to be honest, I didn’t really have to make any compromises. I mean, the organisers take this festival incredibly seriously, they are not just going to hand me total freedom. So they made me justify what I was doing and why. Why this person was important and relevant within the context, would it appeal to both the international audience and the Polish audience. My experience of this festival has always been either at the opening weekend or the portfolio review weekend. People come from London, Riga, Italy, America, they spend three or four days here and go home, but the festival is ultimately for the Polish audience who are here for a month and who can come and visit whenever they like. So there were a lot of hard questions being asked. Is this going to translate? Is it relevant and interesting here? Will it challenge the viewers? (Which is a good thing.) But will it be too challenging, is it too photoworld specific – so that people won’t get it if they are not photographers or if they are not aware of everything in photography? But I felt like I could answer those questions pretty accurately and well.

And you have your own show opening today – about researching your family roots and history. Could you tell more about that?

I rarely include myself in things that I curate. When I started SeeSaw I put myself in the first two issues, this was when I was 22 or 23 years old. Then I got a letter from a photographer who I didn’t know personally, but whom I really respected, Richard Misrach. He e-mailed me saying “I really love your magazine and what you are showing, and I really like your way of writing and how you are interviewing the photographers, and I like some of your work, but make sure that you don’t make this a promotional tool for yourself. If you put yourself in every issue, it makes it seem like you are just doing this out of selfish reasons.” That wasn’t my intention, I was just excited to show my new pictures to people, but I think it was a very good point. I’ve never really included myself in a show that I curated.

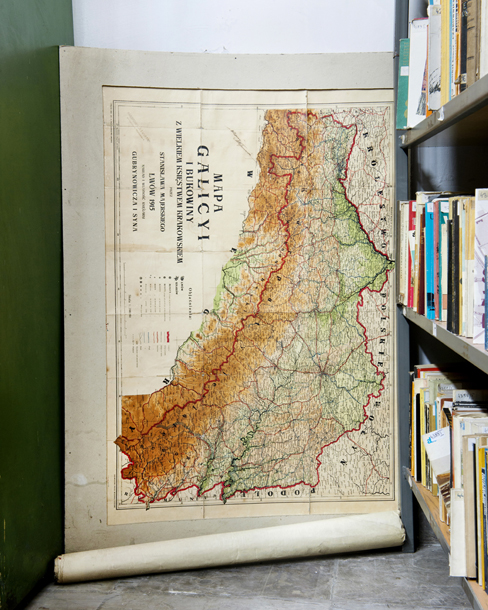

But in any case, the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow hosted exhibitions for the festival in previous years, but the shows haven’t really dealt with the museum or with ethnography necessarily. And this year the museum said they really would like to do a commission or have work in there that deals with the field, that it makes sense to have in this space, not just a random show. Then I went to visit the museum with the festival director at the time, Karol (Karol Hordziej – E.G.). We were wondering through the museum – it is the most amazing museum. I was saying how much I loved it and he was really surprised how excited and enthusiastic I was. He was pointing out things that related to him and his family history and I was thinking: “Oh yeah, my great grandfather came from Poland and I have these connections as well.” A few weeks later Carol approached me and basically said: “Why don’t you do a show there?” It was tempting, why not. I loved the museum so much, so I said “yes”. A lot of photographers, artists and writers have done this type of project, where they go discover their roots and find a village where their grandfather lived. In terms of the project I didn’t want so much to visit the place where my great grandfather came from, it was much more about how this museum can teach me about my family, the type of culture they came from. So I started investigating that, and during that process I also became really fascinated by the museum itself. It’s almost like a village itself. 30 people that all come to this building every day, some of them have been there for 30 or 40 years, developed their own customs, rituals, have handmade artifacts. I almost became an ethnographer of the ethnographers. So it was both me discovering my family history, but also me discovering what it meant to be an ethnographer in that museum.

How do you manage to do all these things? You write about photography, you curate, you are a photographer, you are a tutor.

(Laughs) I don’t know, I just don’t like to be bored. I try to squeeze in as much as I can, I’m terrible with saying no to things, especially if they are exciting and interesting opportunities. I tend to take on too much and then try to catch up (laughs). Prioritize what needs to get done first, which deadline comes sooner. But I really enjoy being involved in photography, being a photographer that is also interested in curating and looking at other people’s pictures and researching other people’s work, trying to write about it and trying to articulate why I like stuff. You see a book or a body of work and you know you love it, that it is something that resonates with you, but its a real challenge to say why. This is a constant with my parents or family, people who aren’t involved in photography. I show them Jason Fulford’s book and I’m like – this is the most amazing photobook I have seen in the last six months! They open it up and ask: “But why?” It is a real challenge to answer that.

If we go back to the similarities between photography and writing – almost everyone can enjoy a great novel, but photography often acts like it is just for people who are students, who are writing about photography, photographers themselves. There is this limited audience and it’s hard to open it up.

Yeah, it’s true. Maybe because it seems that everybody can take a picture, it’s easy. I don’t know why it doesn’t apply to writing, why people appreciate novels. Most people appreciate novels because of the really good stories. I think a lot of photography appeals to other people because it’s exciting and adventurous. But then there are a lot of novels that are much more settled and interesting. In photography there is this constant – I could have done that! But you didn’t, you know, and this person did and they have done it for a reason, not just because they could. Part of what I try to do is to articulate and justify why I think photography is an important medium and certain artists are interesting not just to all the photo nerds, but also to other people. But I don’t see myself as some sort of savior trying to get out in the world to profess photography. It’s much more about trying to figure out why I like it.

What’s the next challenge?

Krakow has been all that I have been thinking about for the last two or three months. So I’m going to take a holiday (laughs).