Interview with Andrea Copetti, founder of Tipi Bookshop

Andrea Copetti is the founder of Tipi Bookshop, a Brussels-based bookstore devoted to self-published photo books and small publishers. Andrea Copetti was recently in Riga for a conference on book design and publishing. Shortly before it, I met Andrea for a conversation.

The Tipi Bookshop has been active for some years now. How did it start?

First of all, I had to find a place. It was very important for me to have a physical space beside the virtual site. It was back in 2013. For a year I renovated the place. To fill it with books, I had to sell my own books, mainly to friends, to buy new books.

In one year I was able to buy back my books again. In the beginning, I felt that there was a need for a place like Tipi, where artist books could have their first exposure in a brick-and-mortar space. At that time in Brussels, self-published books were mostly seen on the floor next to the owner’s counter. I knew from the start that I wanted to mix all the different kind of photographers, whether they were known or just emerging.

The fuel for the bookshop and me comes from the community behind Tipi. After including a book in the shop, most of the time I like to keep up with the artist – to build a constant communication and exchange of thoughts about their work. I also try to buy the books and not to have them on consignment, as the creative and selling energy is different. It’s not only about selling the books. I do some additional things like filming the books and mixing videos with music (with the help of Fabrice Havenne ). Another side project is to hang large format images on the outside rolling shutters of the shop. Letting the images face the city is very important, so that people are not just confronted with advertising images. An image which doesn’t sell you anything is very refreshing, I believe.

What does the word Tipi mean?

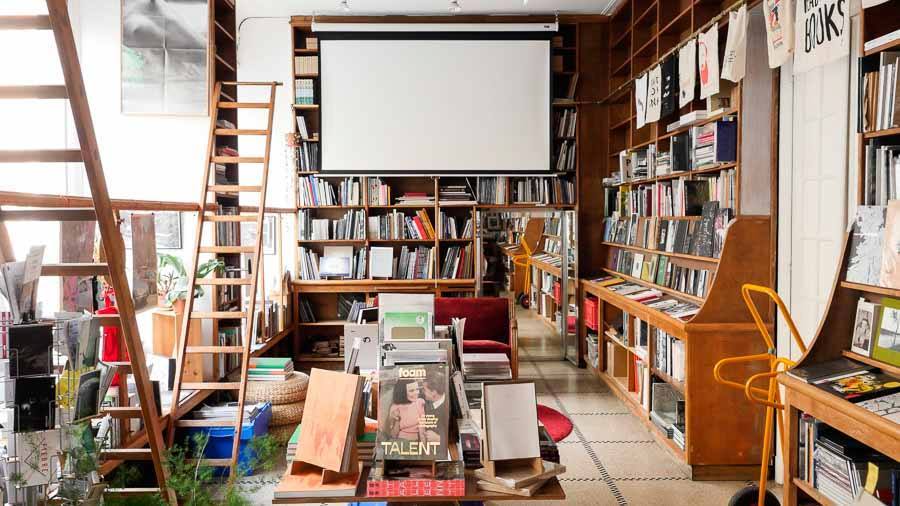

The word Tipi comes from the Indian word meaning shelter, but there is no connection with Indians. As you look at the space itself, it has no angles. There is circular movement and everybody moves around. The place is meant for communication and circulation of thoughts and ideas. For me, Tipi works more as a metaphor than a reference to some secret Indian roots that I don’t have. I am Italian, both my parents are from Italy, but I was born in Brussels.

Can you describe your daily routine as a bookshop owner?

I have a routine, but I don’t have a schedule. I am working a lot, whether at night, when I am doing the packages or early morning when I am often going to the flea market to find some images. My daily routine is waking up at six thirty, walking my daughter to school, going to the flea market, having two to three coffees, opening the bookshop until five. After five, I switch my cap to be a father again and then I am doing the packaging until midnight. The exciting thing about the bookshop is that I never know if anyone will come in during the day to ask me to review their books, so if anyone pops in and I have time, I review them.

How it is to manage the bookshop alone?

I always try to put the bookshop in first place. I don’t feel at ease when the focus is on one guy running the shop (maybe this is why the bookshop doesn’t have my name) as I want people to focus on the books. But this comes at a price, so often people are expecting to see me when they come in to ask something. I haven’t found someone to replace me, so when I’m away at festivals, the shop in Brussels is closed.

What is your approach in selecting the books?

It is a constant search. I also go to many festivals around Europe, where I meet the artists and discover books for real and not just by mail. One of the latest and most incredible festivals was Gazebook in Sicily.

In books, I like how artists have the capacity to turn an invisible subject into a project. My point of view on bookshops is that they should never be neutral in their selection, you should be subjective all the time, and even more, have an opinion on everything. One of the beautiful aspects of a photobook is that it is like a travelling ticket. It can either teleport you to the middle of a country struggling for peace, to an ecstatic experience or just a family journey. A good example is Michal Iwanowski’s book – Clear of People. Here the artist brings the reader along to retrace a journey, originally made in 1945 by the artist’s grandfather and uncle. Through a politically charged and precarious landscape, you discover this 2,200 km fugitive odyssey from the prisoner-of-war camp back to Poland.

I’d like to think that there are two kind of books – “the croissant photobooks” – the ones everyone knows what to expect from, and “the blind date photobook” which can be challenging in the beginning for everyone, but if you let yourself go, you might enjoy it a lot.

How do you arrange the books in the store?

At Tipi, I have mixed all the books for 2 years and it was a rather complicated task for anyone to find anything without me. I had to do it in order to tame and find my own order of things. By mixing them, you are creating a spark. People might not understand it at first, but they will follow it. Sometimes I am moving books around to see how people are reacting. It is exciting to do research on books in the shop, not only about books.

After these 2 years I have started to place books in a constellation, not in a straight line, so that books can speak to each other on many levels of reading. After a while, people asked me for a bit of a system. To give them some clue on how to find the books. I created 5 segments: urban stories and landscape, Belgian, Asian, politically engaged and personal stories.

It is interesting that Asian books have their own section. Why is that?

The knowledge about paper and printing in Asia, especially Japan, is incredible. Their relationship to layout, binding, use of paper is different from Europe; they have their own printing and publishing eco-system.

You deliver books in unique packaging, made of a collage of imagery. Can you tell me more about the creative side of the packaging?

If you are just selling books and not doing anything creative, it gets boring. My artwork mainly happens during the night. It is essential to find a poetry in our daily routine. For me it is creating collages for my packages. I used to use imagery found at the flea market, but now the creative aspect of the packages has changed, as I have shifted from vintage pictures to the French magazine, Paris Match, starting from the sixties. The freedom I seek in the magazine and then in the collage, is the freedom I am looking for in the book, artist, designer and publisher. The collage has to be authentic. That is the exciting thing – not reproducing the image, but using it only once, even if it is a rare photograph from a 1968 student riot in Paris. It is a poetical risk I take.

As a bookshop owner, what is your view on how the self-publishing scene has changed?

I’m not saying that it is because of me, but, at least in Brussels I can see that more and more shops have an eye on different kind of photo books. It encourages artists to work and complete their work. With self-publishers – the more financially unstable the artist is, the more risks they take. They have a greater sense of freedom as they are not targeting anyone specifically, just sending out their stories. I think it is very courageous to do that. On the opposite side, sometimes artists come in to show their book, expecting that the label “self-published” will be their ticket to be bought for the shop, but it doesn’t work like that. The story can be good, but if the paper, ink, layout is not good enough, it ruins the story and the book.

Any future plans for the Tipi Bookshop?

Lately I started to work on a new project, to create a workshop space behind the bookshop. A place to invite artists to do research on their stories within the framework of a book. It is going to be launched next year, so I would say, it is slowly growing.