FK asks – How do you edit your work?

Kārlis Bergs:

The way I select images for each project varies. Lately, the editing is already taking place in the shooting process, even if I only succeed in capturing a few shots that seem suitable. In my opinion, editing during the process of shooting allows you to understand what you already have and what you still need. When I arrive at a book or exhibition, I usually act at the last moment. This does not mean I have not thought about it before, but when I feel that the right moment has come, I quickly and uncompromisingly assemble a sequence, often leaving out the shots that seemed irreplaceable at first, but have lost their significance, since not everything can be included.

Laura Kuusk:

When I select images for a sequence- either in a video or photography series- I think about time. The time that the person would spend giving attention to my work. And I try to make the best usage of this time trusted to me. Therefore I try to cut out everything that can be taken out, and go over the editing many times before I publish anything. It does not mean making everything short and sharp – slowness or unsharpness or repetition are also necessary. But I want to be precise in it and know what I am doing, which experience I want to convey through this visual matter I am making.

Alnis Stakle:

I do not have one specific method or criteria for editing work. In the case of each particular series of photos, there is a conceptual frame that determines the choice of photos, their sequence and all other issues of the materiality of the photograph. My series of works are created very slowly. Sometimes even over 10 or more years, and in the long run, everything becomes clear.

Julia Borissova:

I just make dummies, constantly make prints. It is very important for me to have physical, tactile contact with my work. After the first dummy I create the layout in InDesign and then I make a new dummy again. What to show and what not to show – it depends on the idea of the book, the book must be cohesive and my message must be clear, so I throw away unnecessary pictures without any regret. If I think that everything is right, I prepare a layout for printing. The process of creating a book can take a long time, maybe one year or more, because before I start working, I do research on my topic and this is the most exciting time – I’m looking for inspiration in flea markets, reading books, watching movies.

Visvaldas Morkevičius:

I love to have time for the sequencing and not to rush at this stage. Time gives a better chance to keep some distance between the work and my personal relation to it (of course, impossible to lose it at all). I like to get back after a week or a month after doing other things and see it with “fresh” eyes, rather than forcing myself to do it right now. The main thing that makes editing way easier for me is a layout (I got the tip about layouts from Andrew Miksys, he mentored me on my first book Public Secrets and it helped me a lot). It creates a structure and then I start to see how images talk to each other, if a pause is needed or sometimes I may even reconsider some images deleted from earlier sequences or take something out. After that I’m trying to analyse the flow of the sequence, if there are some points that bother me, or places where it becomes boring or something is repeating itself. Then I look for a way to fix it until there are no “errors” left.

Maija Savolainen:

It’s really random and it really depends on the context. When working with space I often use the space or also other elements than just images to create narratives. When working with other platforms, for example online publications, then the whole thing just has to rely on the images, which I think is harder. With individual images I always try to feel if they can sustain time. Often it helps if I think about a picture as an object and try to imagine having it on a wall in my home. If I think I could put up with it still after some years, then it might be worth publishing.

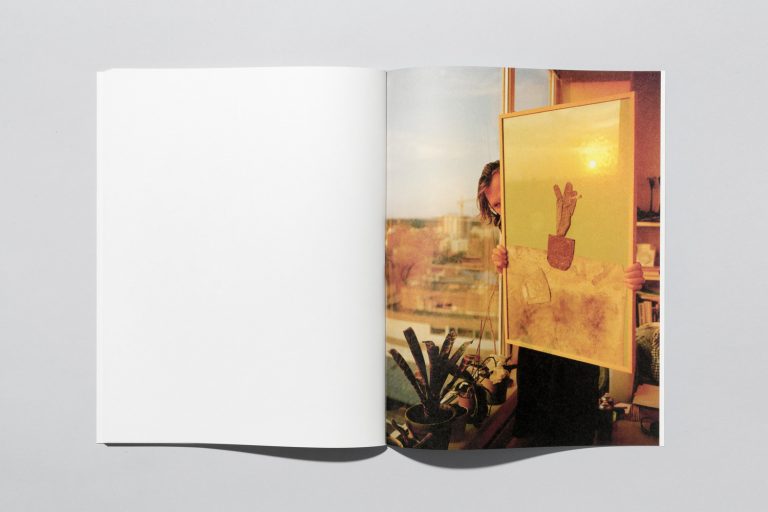

Peter Puklus:

I believe editing is one of the most important parts of the entire project regardless of the topic, medium or presentation. This is when you formulate your message, put accents and cut the bullshit. A sort of last chance to be able to influence the future direction of what you’re gonna say. It being so, I try to allocate enough time and energy to this component and I’m not afraid to ask for help if I need it. For me the never-failing strategy is to print out all th parts in small format, draft quality and to start playing around with them either in a small-scale architecture model of the exhibition space or anywhere else where they can stick around for a while. This is for example how my studio looked like when I was working on editing my book The Epic Love Story of a Warrior back in 2016.

Arnis Balčus:

This is the most complicated stage, since the narrative is articulated from the images. Typically, after the first edit I print the photographs in a small size, put them on the wall or spread them on a table. And then I look at them, think, add something and take something away. Sometimes this can last forever and it stills seems that something isn’t right. I usually start by choosing the so-called key images that become the narrative core. Decisions can be both rational and intuitive.

Sergiy Lebedinskyy:

I don’t have any particular algorithm, mostly after I’ve made a couple of good images on a particular topic, I continue to build up a project having these first images in mind, like building a house, one brick after another one. So I’m thinking about the sequence already while taking pictures.

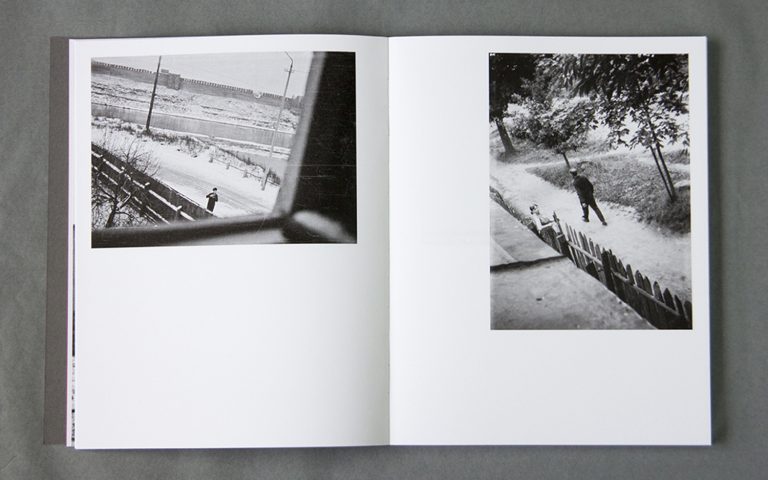

Maria Kapajeva:

It is all very different for different pieces of work. My work is often led by the objects, stories or images I come across or collect. But if I work with lots of images by building up a narrative from them, like in my book You can call him another man, then it is more about my own experience of the images I select and my imagination regarding how viewers / readers will experience them. For that book, first I selected the images from my father’s archive which intrigued me the most: the ones which do not look like family photos at all, or, in which I was puzzled about what is going on in them and / or why they were taken in the first place. Then, I placed them all on the studio floor and moved them around creating various narratives, stories, connections and patterns, until I exhausted this process and felt satisfied with the result. It is also important to have space and time for it. I was grateful to be invited to the residency at Four Corners Film in London to develop my project, so I could use their studios and also have enough time to think, to experiment. But, even one empty wall in your room can do that job and it gives you the possibility to leave the images on it for some time, to see them all on one wall, to pass them time-to-time and to move around it as part of the editing process.

Dragana Jurisic:

I work with a peer group. Once I get to the first draft – I share my work with about 10 people whose opinion I value and ask them to tell me three things that are wrong with it. Once there is a consensus around the specific issue, I listen and fix things. The point is that you have to be open to criticism from early on if you want your work to be strongly built and fly.

Andrew Miksys:

It depends on the situation. When I’m making a book, I like working with a designer who understands book construction and how to make a template of image sizes and a sequencing that fits the design. If I’ve been working on a project for many years it’s not easy to see the images objectively. Sometimes a designer can bring a freshness to the design. For exhibitions, I’ve started to think that less is more. You don’t have to show everything. It’s more important to make an aesthetically interesting installation, instead of trying to show lots of images.