Women of the world, unite! Interview with Marge Monko

Estonian artist Marge Monko (1976) has been interested in the representation of women through issues of labour, women’s rights, and women’s body in post-socialist context. It can be seen in such works of her as I Don’t Eat Flowers, 8 Hours and Nora’s Sisters. Desire for consumption in modern capitalist societies is manifested in her video work WoW about the diamond industry. Working with photography, video and installation, Monko shows her feminist voice fervently. She wishes that the art world wouldn’t be only aimed for single, independent operators, constantly ready to travel but more adjusted to different needs. Her installation I don’t know you so I can’t love you was part of the inaugural of RIBOCA 2018 in Riga. Previously her works have also been shown at Riga Photomonth twice. Marge Monko studied photography at the Estonian Academy of Arts, as well as at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. From 2013 to 2015, she participated in the two-year studio programme at the HISK in Ghent, Belgium. Monko is the 2012 laureate of the Henkel Art Award for Central & Eastern Europe. In 2015 she was one of the first recipients of the national artist wage (2016–2017). Her works belong to the collections of numerous art museums. She has published four books with Lugemik. Since 2017 Monko has been working at the Estonian Academy of Arts as a professor and head of the Photography Department.

Do you remember when and why you decided to become an artist?

I never consciously wanted to be an artist. I always connected art with being able to draw beautifully. This was not my case and I also didn’t know much about contemporary art when I was in high school. My interests were general, like, theatre and film. I was also interested in photography, and I somehow got this idea that I would like to study photography or, at least, would like to start with photography in order to move towards film. These were vague ideas that I had when I graduated from the high school and then I realized that if I wanted to study photography, I really have to have a portfolio, at least, some images to show at admissions. I thought it was too early, therefore I went to study languages to the Institute of Humanities. At that time I also bought my first camera and started to take some images. I got accepted to a vocational training of photographers, a very applied programme. When I graduated from there, some of my course mates said: “Listen, the new photography department is open at the Estonian Academy of Arts, and we are going to apply.” I thought, why not, I will try as well, and I got accepted. But I remember when I was sitting in the corridor, waiting for my turn, I had no clue about art photography. There were these books they had prepared for the applicants to browse through and I happened to take one by Cindy Sherman. I don’t think that I really understood what was in the book, but when I was at my interview, they asked me if I could name some artists working with photography. I said: “Cindy Sherman!” You see, my journey was completely random but already during the first months, I understood that this programme was for me. It was a very happy coincidence.

The studies enlarged your understanding on what photography is and what it can be.

Yes. And also what art can actually be nowadays, hand in hand with critical thinking. I also started to see myself as someone who could act in this field. Because previously, I didn’t have any connection to the art world.

At the beginning of your practice you were making more photographs, then you switched to working with found imagery. Is the reason simply the subject matter?

It’s a good question. When I was studying, me and also some of my colleagues, we were influenced by the Helsinki School. I was very drawn to staged photography, kind of tableaux images, working with a model or a dancer, or an actor. One of my first projects involved these very staged scenes. Then I grew out of this. Around 2008 I got very interested in the subject of labour, in the context of post-industrial situation. I am still interested in what conditions and how people work, how important it is who you are professionally, how it makes your self-image. However, I was struggling to bring it forward; I came to a dead end with this subject. I have always been interested in history, and also historical, archival images, the representation in magazines, or newspapers. I started to collect different images that I was drawn to and, at some point, I started to order a lot of advertisements from eBay. They were ads that you see in the magazines, but these were ripped out and sold as separate images. It’s unbelievable how many different images from many decades you can find there. As I started to have a small collection, and I decided to work with those images.

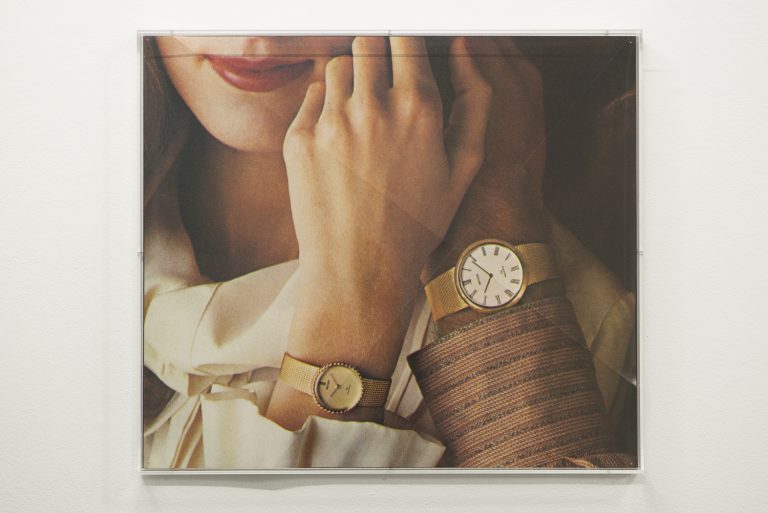

How do you choose the topics? There are a lot of advertisements for watches, and you have a series Ten Past Ten but were you looking for the watch ads in particular or chose the topic from the pile of images you had?

When I bought the first ad, which was a wristwatch ad, I was very fascinated by that image, how carefully it was composed, how the semiotics of the image worked. I started to look for more, especially the ones which featured both, male and female hands. They created different narratives which were actually happening outside the frame. Inside the frame, there were a few but very precise details, a constructed narrative. I was fantasizing about the different “outside the frame” scenarios. These two people whose hands we see, are they married? Or is it an affair? Is it past 10 in the morning? Is it in the evening? Are they on vacation? Are they in the office? It was very intriguing. When I bought this first image, I had no idea about this convention of using “ten past ten” on the watch ads. I started to look for more information about this fact. You can find all sorts of very interesting information, involving a lot of fantasy, even conspiracy theories, like that was the time when President Lincoln was assassinated.

Not only Ten Past Ten, your work features hands frequently. What is their connotation?

The focus on hands started mainly with this work, I think this series was a poignant example in how hands are used in the ads in general. Hands have very different functions on the images, and especially, if you have to present something, they are used like tools. They can be a pedestal, or a stand. Conceptually it is different from how Aristotle put it. He was talking about hands as tools which are used in order to make further tools, however, in advertising, the hands are used as tools to present commodities, or to give an idea of their dimensions. It was interesting to think about it in a philosophical way, as well. So I continue using the hands and, I still like thinking about it, how to proceed with the idea of them as tools and transformation. Nowadays we can take it even further when we think about the screens and how we swipe them. For instance, for the installation of I don’t know you so I can’t love you I made photos of a couple where hands have a special focus but here they are representing a digital longing – the physical touch which is missing in the digital communication.

You don’t explain your work much but instead let the viewer decide for themselves, to question. It seems a playful attitude in overall serious topics you explore.

I think playfulness is very important. Part of the reason why I stopped working with the issue of labour was that I was missing the aspect of unknown in my work. My work has always been very well considered from the beginning. When I had the idea, I knew how to execute it but I feel that something got lost in this process. Then I reconsidered my practice. When I was in Belgium for two years, taking part of a post diploma programme in the HISK, I basically didn’t produce anything serious. I was just trying to figure out; I was testing a lot and failing a lot, too. At least, I managed to find the new approach. I remember, there was a strong attitude in Belgium about not presenting any text for the works in the gallery. I consider that lazy. There can be occasions when we don’t need it, if it’s justified. But if it’s becoming an attitude, then I would say it’s very often the laziness. When I had my first solo show in Tallinn after coming back from Belgium, I also didn’t add any text, there were just the different works and their titles in the gallery. It was received here as something courageous. Now I think it was a bit extreme, I wouldn’t work like this anymore. It was clearly the influence that I brought back from Belgium, although I didn’t really subscribe to it while I was there.

What do you teach your students?

They definitely need to write the statements. I know it can be difficult. For myself, as well, if I need to submit it somewhere, I struggle a lot, I postpone it forever, I really need to force myself to focus. It’s very rewarding as well, you need to do it from time to time. This is what I teach my students – however hard it is to write about your practice or single works, it’s good for you. It’s like going to the dentist, it’s just something that needs to be done.

Do you think there are any expectations to artists?

Oh yes, there are a lot of them. Sometimes it can even be a bit too much. Of course, it depends on the institution and the level of communication, but sometimes you are asked to do a lot of cognitive work by submitting all sort of texts and information. I feel that this work can actually be done by the people who are hired by the institution. As to the public, I think it depends on the work. If your work, for instance, is based on research, or using a very specific method or materials, then I think it’s just generous to provide some details to the viewer.

What is your art making process like?

I am working on something new right now. It’s a mess, and it’s very difficult to rationalize. But overall, it has been like this for some time – I collect images that I’m fascinated by. Some are done by someone else, some are my own images, and then the images are leading the way. There is a lot of processing involved. Sometimes I try to analyze why I would like to work with those particular images or why I like them. Then I’m trying to find something that can go with the images. It’s a step by step process.

What are you working on now?

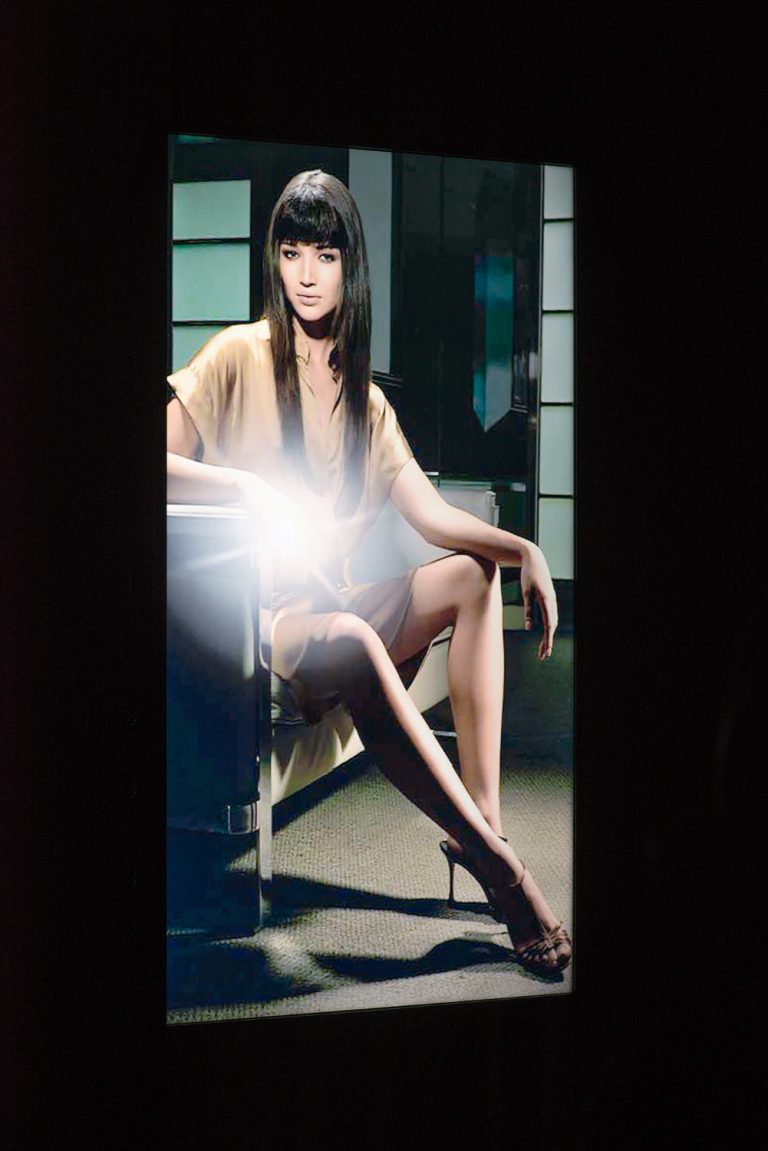

I’m preparing for two duo exhibitions. It’s a coincidence that they are happening on the same year but with Covid-19 interfering in exhibition schedules it worked out like this. There’ll be an exhibition in the Kai Art Center with Gabriele Beveridge in September where I’ll show a new video inspired by hosiery commercials and a series of photos of shop displays which I’ve been doing since 2014. Another duo show will be with Maruša Sagadin both in Tallinn and Vilnius. She is an artist from Vienna, and works with sculpture. We are friends and I really admire her work. Her sculptures are addressing the connections between femininity and the architecture, and how it constitutes in the public space. We share a lot and I thought it would be great to make an exhibition together. I have a couple of self-portraits I have done two years ago and have never shown. I also have a couple of images from the packages of the Soviet time perfumes called Sasha and Natasha – portraits of the models that are very telling for the people who were children or adults during that time and who still remember those products. These are the images that I want to work with and I’m trying to find the connections. It’s a bit of a struggle, but I will find the way, I will untangle this knot.

Your video piece Shaken Not Stirred talks about personal and professional experience of three different people after the collapse of the Soviet Union. How were you at that time? Do you have memories of Estonia becoming independent again and the transition into new democracy, economy and values system? Was the video made from your memories at that time or from a perspective of an adult that expresses the criticism?

My first kind of impulse was to tell the story of three people – a cleaning lady, a business woman and a bartender who have all been going through different transitions during their lives. The idea to make this film came after the financial recession, in 2009. I thought about the topic of labour again, and how a couple of generations of people in post-Soviet countries have been going through very profound changes in their professional lives. First of all, the transition to capitalism from communism, then the financial recession, when a lot of people also lost what they had gained during these, less than 20 years of independence, of capitalism. I was thinking that these are really profound changes in their careers which have had a strong effect on their self-image.

What do you remember from the time when Estonia regained independence? What were the people around you? Do you think that they somehow influenced the artist you have become today?

Since I was a teenager back then, I remember these years of transition very well. I have always been interested in social issues; I was making observations. What you witness during these transition years is transformative. Some people went from poor to rich and vice versa. They were big transformations. My grandparents retired in the beginning of the 1990s but the pensions were so small it was not enough to buy the food. For years they had rented an apartment in a privately owned house and because of the property reform they were evicted from there. So I can’t say that my family was exactly a winner in this situation. I think that this period still hasn’t been represented enough in the culture; there is not enough artwork made to discuss this period but it’s about time to look back and tell these stories.

Have you ever considered making some work on artists’ labour and problems that exist in this professional world?

I always try to be vocal about the issues in our professional worlds. If there is a discussion about the working conditions of the artist, I try to be involved. One work that could be considered is from 2010, I Don’t Eat Flowers, an image where I pose myself as a working woman on the background of the high rise buildings in the Tallinn city centre. I also have a poster version of it. It has been used in different contexts and quite often where the work of artists has been discussed. I am interested to see other people’s work about these issues but I’m not as interested to do it myself.

It’s interesting, I have always consider I Don’t Eat Flowers more about the gender roles. What are the issues on artists’ work in this piece?

First and foremost, it is referring to female labour. The piece was actually made for the March 8th and referring to this post-Soviet custom of bringing flowers to women and forgetting the original meaning of the international women’s day. It’s also logical to see it used in the art context because artists are very often not getting paid for their work. This is maybe a far cry, but if you think about openings, people are bringing you flowers. As a result, a lot of people bring me flowers to the opening but immediately apologize: “I know that you don’t eat the flowers, but I still brought you these.”

You have worked a lot on issues of the 20th century – labour, equal pay, women’s rights, women’s body and others. And a lot of them are still problematic today. Is there anything particular to the contemporary world you are interested in addressing?

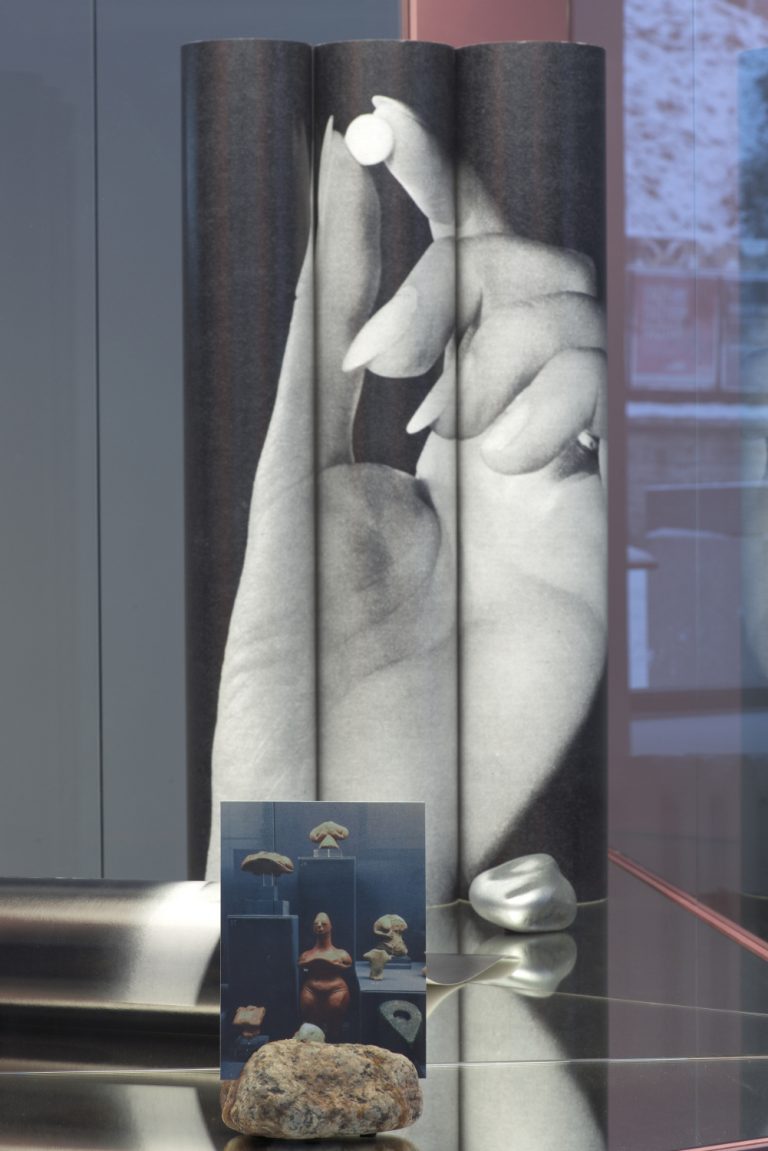

I’m very interested in reproductive issues. It started through another work about the representation of diamonds, and how the narrative of the romantic love has been used in order to promote and sell the diamonds, mostly in the Western world. In this installation, which was related to diamonds, I also use some of the images of the fertility statues, which were made of clay and carved out of stone in the Neolithic period. They are these very voluptuous statues, women being proud of the body and holding their breasts. I started to think about the fertility and also the connections between fertility and controlling the fertility and being independent. This exhibition was taking from the ads that were promoting diamonds for women. Not anymore for men to buy them for women, but the women getting their own diamonds; independent power was promoted with these images. It was a shift in the marketing strategy. I was thinking, what makes one an independent woman and came to the conclusion that it’s the ability to control her own fertility. I’m still very interested in how fertility has been represented in different cultures and in different times. And also, now in these struggles that are happening in Poland, for instance. It’s our neighbouring country and it’s unbelievable that things can go this far.

Diamonds and Pearls are Made for Girls – how harmful is a myth that women need to accessorize?

I think it’s as harmful as any other myths about female beauty. I think it’s all connected, like beauty products that are advertised and aimed at women and this whole industry that is promoting it. And through promoting it, they promote certain narratives, which are very narrow, and very normative. Pearls and gems are not bad for themselves. Right? I’ve never held a very expensive gem in my hand, but when I see the images, I think that they are really beautiful. It’s a complicated work and I don’t think that they shouldn’t be making jewellery and that jewellery shouldn’t be worn, but I think that the narratives coming with these accessories, need to be reconsidered and reconfigured.

And then there is a whole unfortunate truth behind acquiring the diamonds and gems too. None of the big companies would mention that it is a dirty business.

Yes, this is even a more profound issue which is related to capitalism, the way capitalism really works and how exploitative its mechanisms are. Creating and promoting the myth, and spreading them through marketing, it’s part of this system. Then there is the hidden part of capitalism such as labour conditions, exploitation and colonization.

What is the role of photography in the production of consumption and gender roles?

I think photography has a very big role in it. It has been for already almost 200 years now, that’s why I’m also very fascinated by it. The historical and the mid-century images that I’m using in my work have meta levels how photography has worked in order to bring those narratives to us, and how photography has been a very important part of constructing the gender roles and the representations that are actually creating inequality.

Is there inequality and inequity in art?

I think it’s another very serious issue. There is a lot of inequality in arts, people working in the arts and in the art institutions, they have to work in order to transform it. That is the only way how it can be changed.

Do you feel any inequality as being a woman artist?

I have been asked this question before. I remember when I was younger, I said that I didn’t feel any difference. I was wrong. Of course, there is a big difference, whether you’re a female artist or a male artist, for a lot of reasons, but I think there has been more awareness during the past 10 years about this issue. For instance, there are now a lot of initiatives that bring in the focus the aspect of people having families, raising children and having different kinds of needs. There was a webpage made (artist-parents.com), a proposal for institutions, how to take into consideration artists who are parents, what kind of needs they have; it could be read as a manifesto. I was posting on Facebook that I wish that it existed 10 years ago when my child was small, but I’m happy that these discussions are finally happening. It’s a really big change and I really hope that these changes continue, so that the art world wouldn’t be only aimed at single, independent operators, constantly ready to travel.

What does it mean to be a feminist in the 21st century?

I think it’s the same as being a feminist in the 20th century. Of course, there are different challenges. Because of the former movements, a lot of the issues have been are already, if not solved, then at least, considered. I just remembered that about 10 or 15 years ago, there was a group of French students in Tallinn and they came to meet me. I was talking about my work and also mentioned that my perspective is a feminist perspective. And then one of those students, a female student, was so bothered with this word. She asked me if it was feminism like in the 1970s. So I had to ask if she really thought that all the issues for women were already solved in the 1970s. I think I was considered anachronistic, blindly clinging to the past.

If we categorize anything, your work could be considered feminist.

Yes, of course. And I’m not against it at all, it has been a very conscious decision. I would like to think that nowadays some of those issues that my work is tackling are not so obscure anymore, that we already have some common ground that everybody agrees on, or, at least, understands that structural inequality has been existing historically. When I started as an artist, I had a discussion with some older male colleagues, and they denied this structural equality. It is a “I say, you say” conversation. Right now, we can still disagree but because we have a common ground, we have smarter, more inclusive conversations.

Do you believe that art can have an impact? Can it create change?

In general, the visuals, especially nowadays, but also historically, they have been very powerful on many levels and, in many struggles. In that sense, I think art also has a transformative power. I really believe in it.

If you would remake the slogan “Women of the world, raise your right hand!” that you use in your video work WoW and in the exhibition Stones Against Diamonds, Diamonds Against Stones what would it be and what would it stand for?

What this advertising slogan is based on is basically a paraphrase of the proletariat’s “Workers of the world, unite!” I think I would just turn it back, and I would say: “Women of the world, unite!” I think it has been already used but I think it’s a nice slogan. It’s calling on solidarity. It is much more important than buying stuff.