Latvian photography in the focus of an American researcher. Interview with Maria Garth

Maria Garth is a PhD candidate in Art History at the Rutgers University where she specializes in the history of photography and Russian and Soviet art. Her research and writing are focused on issues of gender and politics in photography. The University is also home to the Zimmerli Art Museum and the Norton and Nancy Dodge art collection, which has the biggest Latvian art collection outside Latvia. By researching the collection, she curated a show at the Zimmerli entitled Communism Through the Lens: Everyday Life Captured by Women Photographers in the Dodge Collection (May 1-Oct 17, 2021), which includes the work of Latvian photographers Māra Brašmane, Zenta Dzividzinska, and Ina Stūre.

How did your interest in Soviet art originate?

I am a PhD candidate in art history at the Rutgers University, and I specialize in Soviet art. I’ve been working on this for quite a few years now, as part of my dissertation research. This exhibition also dovetailed really closely with what I’ve been interested in, which is the history of photography, and how that relates to Soviet photography, in particular. In most mainstream histories of photography, like in the US, Soviet photography often is ignored, it’s marginal. Even with the focus on global photography, within art history, Soviet photography is still something that not a lot of people know about. I’m also really interested in women in Soviet art history. The history of Soviet photography has always focused on male photographers. Everyone knows all the major names like Alexander Rodchenko but women were also there. They were just as active in making work at that time, and they were active members in photography clubs and organizations. And we don’t really hear a lot about that. Learning more about that history and trying to share it with others has always been my interest.

How come an art museum in New Jersey – the Zimmerli Art Museum – has the biggest Latvian art collection outside Latvia? How did this collection come to be?

Latvian art and photography collection at the Zimmerli is a part of a bigger collection that belongs to the collectors Norton and Nancy Dodge. Norton Dodge passed away, but Nancy Dodge, his wife, is a trustee of the Zimmerli Board, and she’s still active. Norton Dodge was a professor of economics at the University of Maryland. I think his first trip to the Soviet Union was in the 1950s, or the 1960s, and he became really interested in Soviet art and began collecting. This collection was put together over multiple decades beginning in the 1960s, and then through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. The collection was donated to the Zimmerli in the 1990s by Norton and Nancy Dodge. But Norton Dodge continued collecting and they also had a lot of works that were stored at their farm, Cremona in Maryland. These works continued to enter the collection, we’re still adding works from Cremona. Norton Dodge was really interested in creating a global representation of Soviet art. He didn’t want to just collect Russian art, he wanted to collect art from all of the Soviet Republics. He traveled to many of those countries himself or he met people who were experts in the art of that country. For the Latvian photography, Norton Dodge worked with Mark Svede, PhD, who is a professor of art history at the Ohio State University now. He was really instrumental in gathering a lot of Latvian art, he’s a specialist in modern and contemporary Latvian art.

What Latvian photographers are included in this collection?

There are so many artists and photographers – Zenta Dzividzinska, Māra Brašmane, Ina Stūre, Jānis Borgs, Valdis Celms, Andris Grinbergs among others. The Zimmerli has done a lot of work to digitize its collection in recent years. Even before the pandemic, they wanted to make it as publicly accessible as possible. So, a lot of it is online. I would strongly encourage people to look through the Zimmerli Museum collection. I think it’s a really interesting and varied representation of Latvian art from the 1960s through the 1980s. The Zimmerli is trying to add more images. Right now, all of the photographers and artists are listed, but not all the images are represented online yet.

How and why did you choose this theme for the exhibition?

I’m a Dodge fellow, it’s a program where graduate students can work at the Museum through their studies. One of the centerpieces of the fellowship is that you do research on the collection and pick a focus for your exhibition. I researched the collection in consultation with the Zimmerli’s curators – Jane Sharp, Research Curator of the collection, and Julia Tulovsky, Curator at the Zimmerli Art Museum. Since my interest was women in the history of Soviet photography, of course, I started looking at the photography holdings of the Zimmerli. I narrowed it down to looking at works by women, and created a list of different photographers from different Soviet Republics of the Soviet Union. And so that became kind of the basis for the exhibition.

Were there any challenges in making the exhibition?

The collection is wonderful, and it’s very big. Before I came to the Museum, I didn’t even know how large the collection was; it was difficult to know even where to start. The first part of the challenge is just familiarizing yourself with the collection, and figuring out what you’re interested in. But that was just a normal part in curating, everyone does that. But more recently, the pandemic presented a really major challenge – not being able to physically go to the Museum and look at works. It’s something unexpected when you go from working in person to having to work exclusively online. Thus, much of the curating work was done online through accessing the Museum database and working with the Museum staff virtually. That’s a challenge that a lot of curators have faced in the last two years, trying to figure out how to transition to working online. And it’s been a great challenge, I’ve learned a lot from it. The pandemic revealed just how important it is for museums and cultural institutions to make their collections and the work of their staff easily accessible online. I think it is creating a lot of opportunities, hopefully pushing museums to put more work online. I think more museums are realizing that they’re serving not just the people in their immediate communities, but that they have audiences all over the world. This exhibition has been something that is interesting to people outside of New Brunswick, New Jersey. Scholars from all over the US and in Europe and Russia have contacted me about it. It’s important for curators, and for museums and academics, anyone who works with this sort of public facing element to really consider what the role and importance of virtual exhibitions is, and to really try to make work more accessible to the public in a way that doesn’t require people to physically go to a location. There’s, of course, so many benefits to physically doing an exhibition, or physically handling an object, you can’t ever really replace that. But I think for the sake of education, it is really important to make things available online. I’m really glad to see that. In the past two years, museums and curators have really made an effort to show events virtually online. So many talks are available on YouTube; it’s been wonderful. I think in the past two years, I’ve probably watched more talks than I have ever in my life and I’ve tried to contribute to that as well.

Will it be possible to see this exhibition in presence in the Museum?

Yes, if the pandemic had not happened, it would have just been a traditional exhibition at the Museum. But then it became evident that the Museum would need to be closed and would only reopen next month. One of the things that we did was to create this virtual exhibition, and to try to do online events and create online programming in ways for people to be able to connect with the exhibition virtually. So right now, fortunately, I’m actually really happy with how this turned out. People can access that exhibition online and have sort of the full experience; nothing is left off. But for those who are in the area and want to visit the Museum, the Museum will be open to the public in September and October. I will also be giving tours in person.

What are the most surprising things that you have learned about Latvian photography, while working on this exhibition?

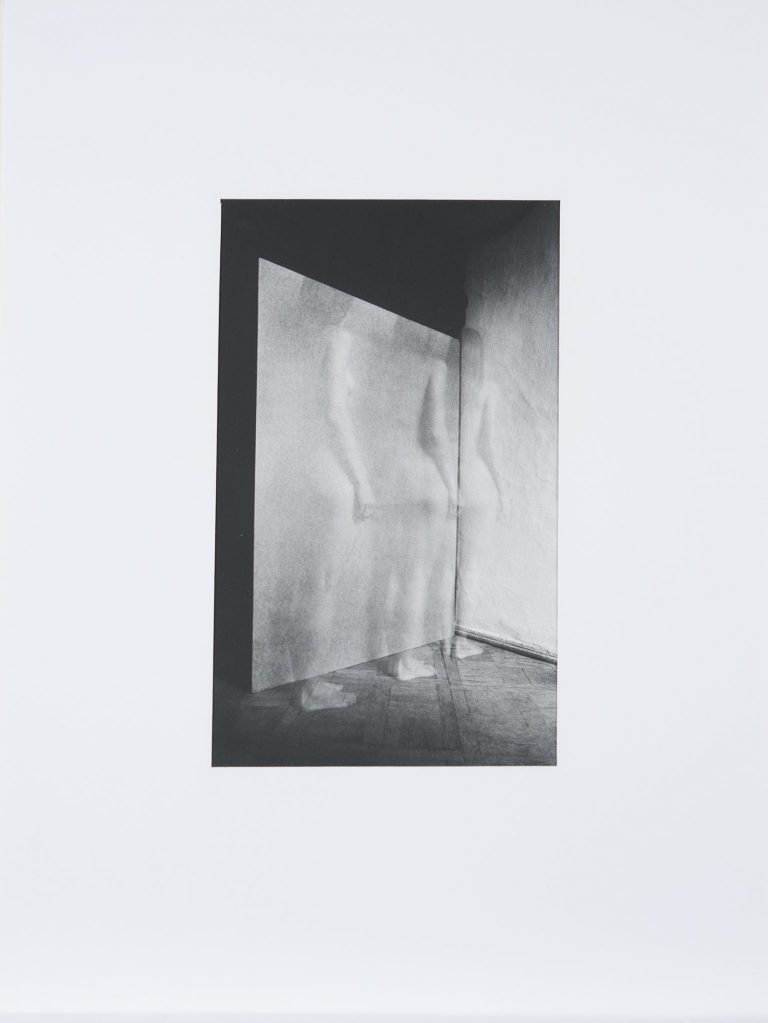

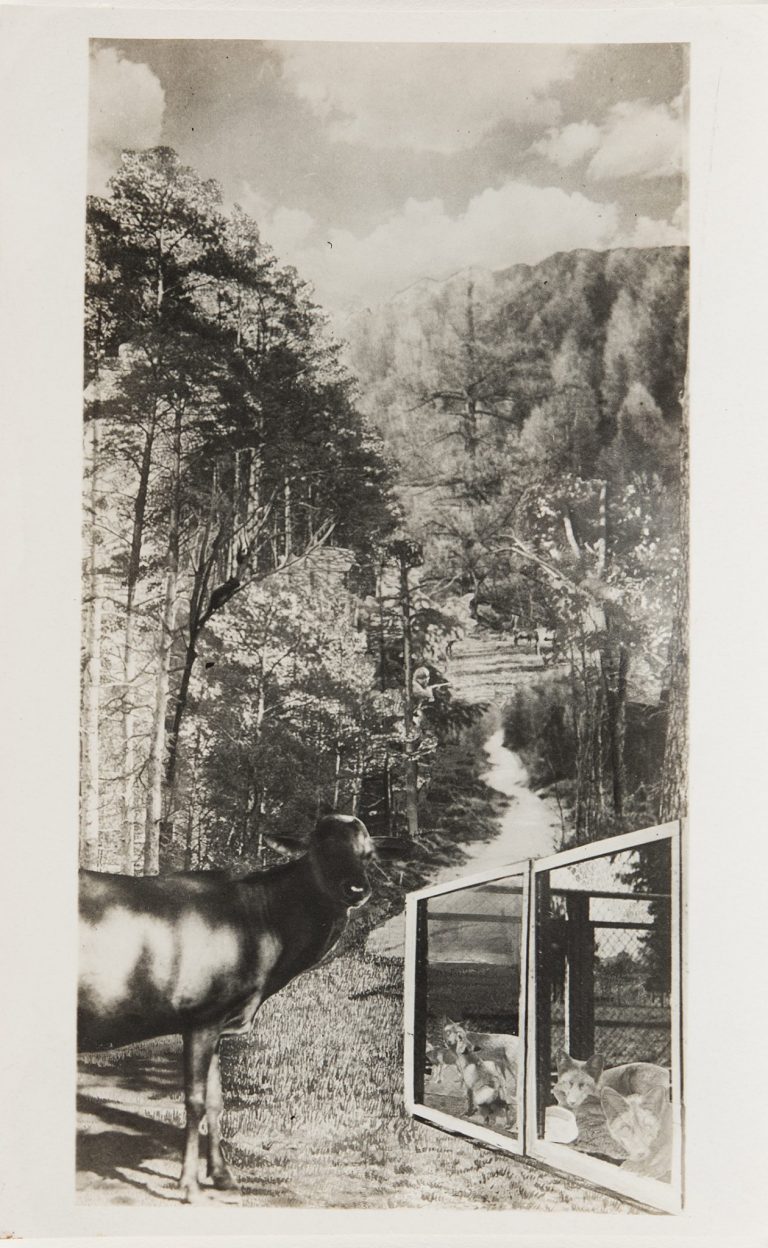

I am specialized in Russian art history, mostly, so I was not as familiar with Latvian photography or Latvian art. I’ve learned a lot about it through this process and it has been really interesting. I’m writing about Zenta Dzividzinska for my dissertation on Soviet women photographers. It’s a really great opportunity to do that, through this collection, I don’t know where else in the US, you could spend so much time with Latvian art. It’s interesting for me, as a specialist of Russian art, to see some of the differences between how photographers in Latvia were working during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s compared to Russian artists. The photography club culture was interesting. It was a major channel for photographers to connect, create and circulate work. That was pretty standard for all Soviet photographers, there were photography clubs everywhere. But within that network, every single location had its own unique way of doing it, its own culture. It’s very much about the individuals who were there. Alise Tīfentāle, of course, has done so much research on that and written books and articles about Latvian photography; her scholarship was really instrumental for me as a way of learning more about Latvian art history. I’m also interested in the way that women were included or made a place for themselves in Latvian photography. I think Zenta Dzividzinska and Māra Brašmane’s stories are really fascinating. They created their own unique approaches to photography under all of the constraints of the Soviet system. They exhibited internationally and were interested in creating connections with artists and photographers abroad. One of the remarkable things about the Photo Club Riga is the involvement of women in the Club from its very beginning, with the photographers Zenta Dzividzinska and Māra Brašmane getting their start in the Club during the 1960s. The Club is notable for fostering an array of approaches to photography, such as self-portraiture, experimentation with different in-camera and darkroom techniques, and nude photography which was very daring for the time, since nude photography was forbidden in the Soviet Union. I have to cite Alise Tifentale here, as she has written about this extensively in her publications.

What is your favorite piece in the collection of Latvian photography?

It’s a really hard question to answer. There are so many but I have to say that Zenta Dzividzinska’s work has been really interesting to me, especially the self-portraiture. I decided to include her in my dissertation after doing this research for the exhibition, her work is fascinating and I’m really glad that her work is getting more attention through the work that Alise Tīfentāle has been doing to preserve her estate. Other historians are also becoming interested in her work.

If you organized another show, what subjects would you be interested in exploring further?

I am close to the end of my fellowship; this project has taken some years to create. There are other Dodge fellows. Fortunately, the program is structured in such a way that there are multiple graduate students working on the collection, and they will have their shows and showcase their perspectives on the collection. As new people work on the collection, they’re always unearthing different aspects of the collection, and making different connections that other people haven’t made before. I’ve been interested in learning about the impact of women in the history of photography. I’m not sure whether I will have another opportunity to do another show but I’m interested in learning more about the history of women in Soviet and Latvian art. In the history of art in general, I think that there’s been a lot of scholarship in recent years on trying to clarify, make it more present in the history of photography. There’s a show right now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, called The New Woman International, that takes work from different women photographers globally, and tries to make an argument for why it’s important to create a history of photography that includes women. So that’s the kind of work I’m really interested in doing as well.

If you could, is there a piece or an artist that you would like to add to this collection?

That’s an interesting question. One of the things that I really like is that the curators Julia Tulovsky and Jane Sharp are always adding new works to the collection. It’s great that this is not just a historical collection, but something where the Museum is always adding new acquisitions and trying to stretch the collection. The Museum is trying to create new connections and to fill in gaps, where the works haven’t been included in the past, such as works by artists who are living in the former Soviet Republics and Russia. There’s an opportunity to make a connection between what people are doing now to how art was made; a lot of photographers are still alive and making work. It’s interesting, like with Zenta Dzividzinska’s show in Riga, to have a contemporary artist, somehow to collaborate with or investigate the work of someone who worked decades ago.