In black and white you have all the colors – interview with Italian photographer John R. Pepper

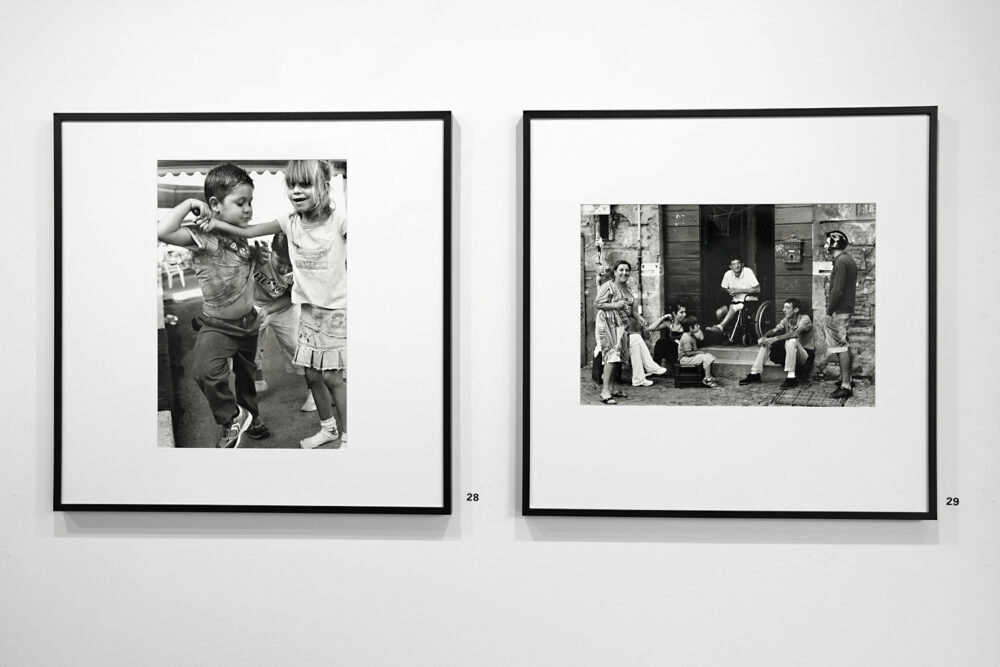

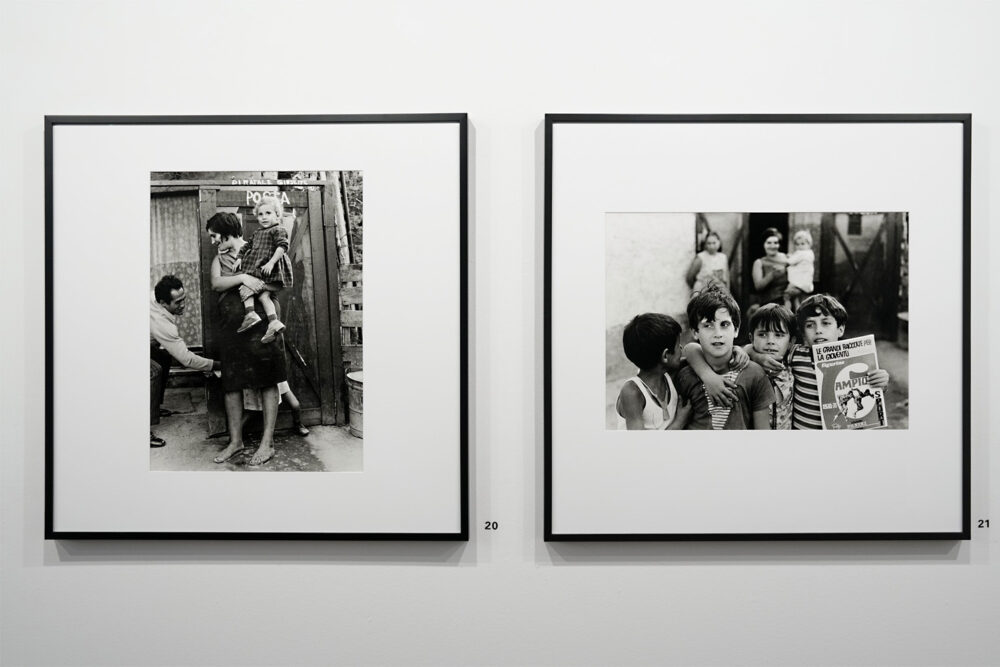

From March 15 to April 19, an exhibition titled ‘Italy, 40 Years: 1970–2010’ by John R. Pepper is taking place at the Latvian Academy of Arts. In the exhibition, featuring 41 photographs, the artist has not included dates on the photographs, as he aims to create a generalization about what Italy is and believes that nothing has changed since the time when he, as a 12-year-old boy, took his first photographs with a Pentax camera.

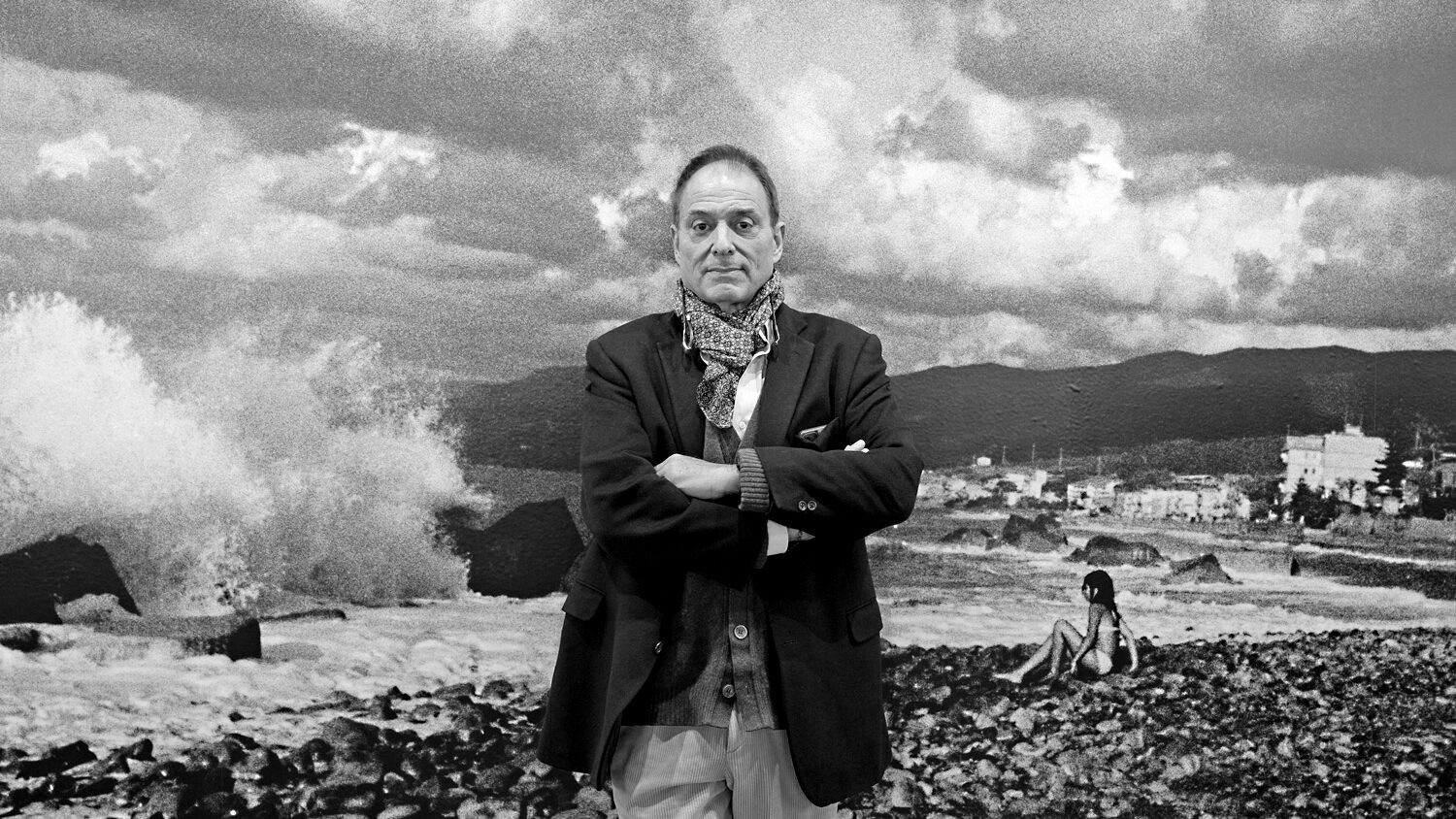

John Randolph Pepper is an Italian photographer born in 1958. He was raised in a family of intellectuals and artists. His father, Curtis Bill Pepper, served as the head of the Rome bureau for ‘Newsweek’ magazine, while his mother, Beverly Pepper, was a sculptor. John grew up in Rome, Italy, alongside his sister, poet Jorie Graham, who has received a Pulitzer Prize for her poetry.

In 1976, John graduated with a degree in History of Art from Princeton University, where he primarily studied painting. He then pursued further studies at The American Film Institute in Los Angeles, CA, where he was admitted as a ‘Directing Fellow’ and embarked on his career as an assistant director.

Apart from his work in film, John Pepper is also a dedicated theater director, having directed plays in various locations including Paris, France, Europe, and Russia. His interest in photography began during an apprenticeship with Ugo Mulas and continued to develop alongside his work in theater and film.

In 2008, he curated the exhibition ‘Rome: 1969 – An Homage to Italian Neo-Realist Cinema’, which toured several venues in the USA and France. Three years later, in 2011, his first book titled ‘Sans Papier’ was published, accompanied by exhibits in cities such as Rome, Venice, Saint Petersburg, Paris, and Palermo. Since then, John has held numerous exhibitions worldwide, showcasing his diverse body of work.

How would you present yourself?

Well, first of all, I would simply introduce myself as an artist. Like all artists, I engage in various activities at times. But I am primarily a photographer, and that’s all I’m focused on at the moment. I no longer direct theater, except on very rare occasions. I directed theater for a long time because working with people is my forte, you see? I photograph people, I direct people. If someone were to ask me what my profession is on the frontier, I would say photographer. That’s what I do. And I only do that. I exclusively work in black and white. I use film, not digital. My equipment includes a Leica M6 and a 35-millimeter lens, and I prefer Ilford hp5 film, which someone is supposed to give me today. I don’t engage in any post-production, any Photoshop, anything like that. What you see on the print is what’s on the negative. However, I would also say that as a photographer, I am also a storyteller.

Why black and white?

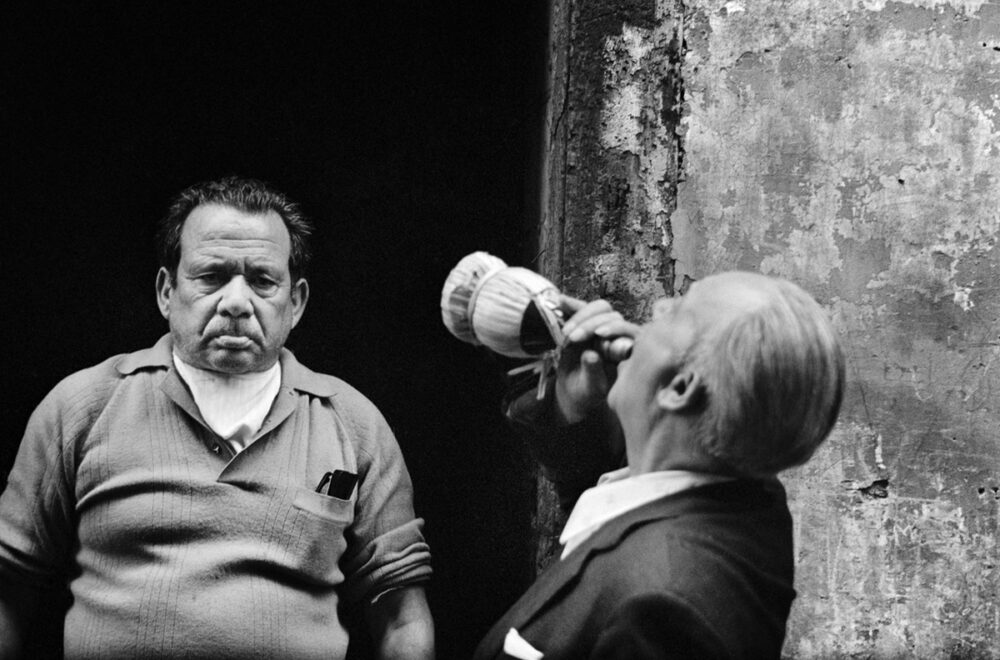

In another language, the answer is really easy – потому что. Because I believe that in black and white, you have all the colors. Colors are fantastic, but color today is often manipulated. I come from the school of Ugo Mulas, Henri Cartier-Bresson, of photojournalists, not street photographers. Because street photography is different; it’s a reductive term. Black and white offers a range from 0 to 9. Color is straightforward. I believe in black and white. When people look at it, they can project their own imagination onto it. Black and white allows for more interpretation. Color gives you the answer.

Tell me about the exhibition. What will people see there? Why Italy?

Why am I showcasing this particular body of work, ’40 Years of Italy,’ rather than other works? Well, for a simple reason: I am Italian, and this exhibition is sponsored by the Italian embassy, led by Ambassador Alessandro Monti. Additionally, over the last decade or so, I have had the privilege of working worldwide, often with sponsorship or support from Italian cultural institutes, embassies, and consulates. I’m immensely proud of this, as it allows me to act as a cultural ambassador for Italy. Italians, as you know, are not a threat to anyone; we’re often perceived as jovial and light-hearted. However, Italy’s cultural heritage extends far beyond the stereotypes of spaghetti, pizza, or famous entertainers like Al Bano or Celentano. Italy has been the cradle of some of the world’s most influential artists, and I believe it’s important to showcase contemporary artists as well. As an artist myself, I feel a deep sense of responsibility to represent my country and remind people that Italy’s cultural richness goes beyond superficial associations.

Why is this exhibition titled ’40 Years of Italy’? Well, it all started when my father, a photojournalist at the time, gave me my first camera—a Pentax—when I was just twelve years old. He was transitioning to a Nikon and passed down his camera along with some basic photography lessons. Often, my mother, a sculptor, would encourage my father to take me along on his assignments, giving me early exposure to the world of photography. Some of the earliest photographs in this exhibition are those I captured at the age of twelve.

In 2010, I returned to Rome from Paris, where I had been living with my family. I felt a strong urge to reconnect with my roots and explore the city where I had spent my childhood—the city where I roamed freely, barefoot, in what felt like a small village. Despite Italy’s transition into the 21st century, the essence of the Italian people and their way of life seemed timeless. It reminded me of the famous line from ‘The Leopard’: ‘For everything to remain the same, everything must change.’ Italy is a paradox—it has evolved, yet it remains unchanged in many ways. Therefore, when I arrange the photographs for this exhibition, I intentionally refrain from including dates. The presentation is deliberately deconstructed, allowing viewers to ponder the temporal ambiguity of the images. A supplementary sheet will guide them through the narrative without the constraints of time.

Where is your home now?

Currently, I split my time between Paris and Todi, a charming medieval town nestled halfway between Rome and Florence, near Perugia. In Paris, I reside in a rather unique setting—a historic establishment called Hotel La Louisiane. It’s quite renowned, akin to the iconic Chelsea Hotel in New York during the 1960s and 70s. La Louisiane has been a haven for numerous great artists over the past century. The hotel’s owner purchased around 70 or 80 of my photographs, intending to adorn the rooms with them. Realizing the potential to assist the hotel’s restoration efforts, I proposed an unconventional arrangement—I offered to exchange nights at the hotel for my artworks. It was agreed upon, and now, I find myself living in this historic hotel. Paris serves as my base as I prepare for my upcoming project.

Tell me about your next big project!

It’s called ‘From Miami to Patagonia.’ I’ve purchased a camper—a 1970s Volkswagen model equipped with a bed, a small bathroom, two cookers, and everything I need for the journey. I’m having it shipped to Miami. Speaking of color… I’ve decided on a distinctive hue for the camper. To maintain its discreet appearance, reminiscent of my own, I’ve chosen canary yellow. To make a dramatic entrance, I’ve arranged for the camper to be lowered onto the Miami port using a traditional rope method, much like in the ancient times.

The journey’s beginning will serve as the opening photograph, captured in vibrant color. As I traverse through various landscapes, documenting my journey, most photographs will be in black and white. However, the final image will be taken in Patagonia, amidst the snowy terrain, with black and white penguins bustling around, all captured in color.

My route will take me through the southern United States, including states like Alabama and Louisiana, which present both beauty and complexity from a racial standpoint. From there, I’ll cross the Rio Grande into Texas, then continue through Mexico, Central America, and down the western coast of South America, eventually reaching Patagonia.

This project will undoubtedly take time, and I’m not yet certain what I’ll be photographing or what the primary focus will be.

What is the future of photography, considering that nowadays AI (artificial intelligence) can create a photo for you, and Photoshop can easily edit and alter images, making it sometimes difficult to distinguish a real photograph from a fake one?

Like many people around the world, I’m both very excited and somewhat concerned about AI. You’re posing this question to someone who still writes letters with a fountain pen on paper. When I have a significant issue with someone, I prefer to write them a letter and mail it. Even when I have people working with me and they’re taking notes on their phones, I request that they use paper instead. And as for reading, I prefer physical books over Kindle. Well, let me begin by saying that I believe there’s good news for analog photography. I truly believe this. Karin Kaufmann and her husband, Andreas Kaufmann, are the owners of Leica. Karin Kaufmann oversees the Leica galleries worldwide. They’ve opened 26 galleries and plan to open four more globally. While Leica does produce digital cameras, through their efforts and exhibitions, analog photography, much like vinyl records, is experiencing a resurgence.

In terms of my work, or for people like me who work in analog, we don’t need to worry about AI. My main concern lies with the terminology of digital photography rather than AI. I view digital as an art form, and it’s entirely legitimate. Of course, if you’re a journalist in today’s world, digital is often necessary due to its efficiency, especially when time is of the essence. However, I believe that digital photography should be referred to as digital imagery. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a suitable translation for this term in French, Italian, or other languages. It works perfectly in English and has a nice ring to it. But the crux of the matter is, it all comes down to what the old-school photographers would call ‘capturing the moment’ or ‘capturing a magical moment.’ ‘Capturing’ is the key word.

And we could easily take photos on the street; people didn’t come to you saying, ‘I’m not okay with my picture being published or even taken.’

You’re absolutely right. In the old days, when you were taking photographs, people would be happy. You had to tell them, ‘Just forget me, don’t look at me.’ They would comply and then move on, forgetting about you. Today, however, people assert their rights to their image.

Once, I was in New York, and I captured an interesting photograph of a father and son. After taking their picture, they approached me and said, ‘Let me see the picture you took. I’m not sure I’m comfortable with you taking my picture.’ I responded, ‘Actually, I didn’t take your picture. I was aiming the camera in your direction, but I was photographing the wall above you.’ Another approach is when you work with Leica; you have control over depth of field. By adjusting the focus, you can capture scenes without drawing attention. By the time I’ve taken the picture and moved on, people don’t even realize it.

But if you publish this picture somewhere, do you have the rights to do so?

All I know is that I’ve never encountered that kind of problem, you know, but it’s also true that when I undertake a project involving people, I have them sign a release.

But the question I often ask myself is, would all the great photographers like Capa, Shaw, Smith, or Dorothea Lange have been able to do their work today with all these issues?

Here’s another way of answering the question: In many cultures, taking someone’s photograph is seen as stealing a bit of their soul. Because it is. I aim to capture a piece of their essence, and in a sense, I am taking it from them. But what am I doing when I display it on a wall in a museum, gallery, or someone’s home? I am giving it back to people. In fact, your soul is enriching other people’s souls. So it’s a cycle. It’s almost like the cycle of life. And that’s the only way I can fulfill my role.

When I give masterclasses or work with people, I always emphasize that when photographing people, it’s all in the eyes. You have to focus on the eyes because they speak volumes. By focusing on the eyes, you delve into the soul. If we believe that the eyes are the windows to the soul, then you’ll understand. But I can’t do my job if I don’t delve into that.

So yes, sorry, it’s what I have to do, and that’s how I do it. After I completed a project called ‘Evaporations’, which was very successful and traveled worldwide, I kept hearing about street photography. I found that term reductive. Cartier-Bresson was not just a street photographer; he used the street as his studio. So, I embarked on a different project. I went to the deserts and spent three years there.

What did I discover? Even in those pictures of deserts, stones, yucca cacti, or rocks, if you look at them in a certain way, anthropological figures emerge.

How would you define a good photo?

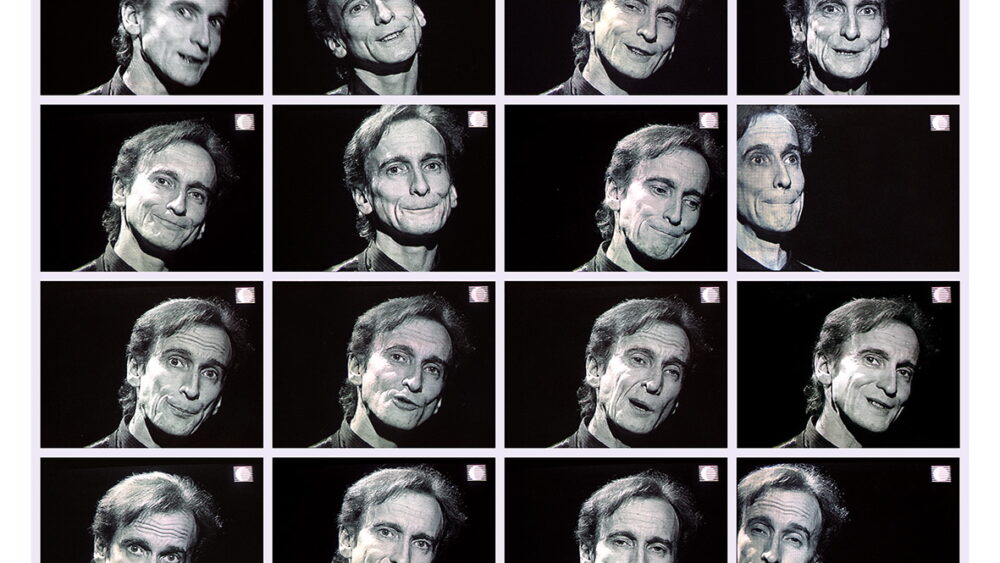

A good photograph must possess two key elements. Firstly, it should tell a story, even if it’s as simple as a dog and a flower. There must be some narrative within the image. Secondly, it should capture a moment. For example, if I have multiple photos of you, some with your gaze directed slightly to the left, others to the right, and perhaps one where you turn your head, I would choose the one that I believe captures you the best. Which one is interesting? Which one tells the story about you? Because if I’m going to display your image on a wall for someone to purchase—because I also need people to buy my photographs—you must engage with me, the viewer. You must be present and connect with the observer.

Additionally, a good photo involves considerations of construction, balance, and aesthetics. Both of my parents are artists, so I grew up with a greater appreciation for artistic freedom. However, when I was a young boy, my father, a journalist, received advice from a man with a French accent—later revealed to be Cartier-Bresson. The man told my father, whose name is Bill, that for a photograph to truly function, it must be able to work even when turned upside down, with its construction remaining sound. If it functions well in this manner, then the photograph’s construction is deemed good. Only after this consideration should one assess the narrative aspect of the photo. Sometimes, however, you just have to trust your eye.

What inspires you?

That’s a good question. I’ll answer it with a metaphor, and through that, I’ll likely arrive at the answer. When I conduct a masterclass or workshop, participants often come and share their portfolios with me. My first question to each of them is: If you could never take another photograph again in your life, what would you do? If their response is that they would feel lost, devoid of purpose, or unable to express themselves without photography, then they belong here.

My identity is deeply intertwined with my work. I come to understand myself better through the images I create. People often ask me how I find certain photographs, what the idea or concept behind them is. My answer is simple: I don’t know. The photographs find me. I’m walking, I see something, and I feel compelled to capture it.

The other day, while working on an exhibition in Paris, I confided in someone: ‘Je ne suis pas bien dans ma peau et je ne comprends pas pourquoi’ (I am not comfortable in my own skin). It dawned on me that I hadn’t brought my camera with me. It felt akin to being a writer without a pencil and notebook. The absence of my tool, the means through which I express myself, left me unsettled. The following day, I made sure to bring my camera. Though I may not have taken any photographs, its presence reassured me that if an opportunity arose, I would be ready to capture it.