Interview with Marc Mouarkech

Marc Mouarkech is the director of the Arab Image Foundation, based in Beirut, Lebanon. Marc was in Latvia this summer as part of ISSP 2019 Photography and the World and gave a talk Politics of Representation.

The Arab Image Foundation (AIF) has been championing photographic material as a means to preserve the history of the Arab region since its establishment in 1997. From the beginning it has worked to create a dialogue between the archive and contemporary art practices. I met with Marc in Zaļenieki during ISSP. We spoke about the beginnings of the AIF in the context of Lebanon after the end of the civil war, questions of representation, as well as what is the AIF today and what are its goals for the future.

I would like to start with some background questions. Did you experience the Lebanese civil war?

No, I was born at the end of the civil war. I was born in 1988, and the civil war ended between 1991 and 1992. I was too young to remember anything from those three years, but I lived through the consequences. Everything that came after, how people dealt with what had happened, the collective memory, the amnesia.

We live in a country that is very, very complex. There are 18 different religions, a lot of diversity, and although we brag about being able to sustain that diversity, it’s sometimes really hard. It’s a constant power struggle.

That was also at the core of the conflict.

Part of it, but there were a lot of reasons [why the civil war started]. It’s a complicated history. The fact that we still don’t have a modern history written about the country, is because, nobody wants to admit or accept any responsibility. Different stories and histories come into play, and each serves a different group, so sometimes you actually wonder where is the truth. I think, that the people who try their best to bring out the truth are the artists. Artists are trying to find pieces of the puzzle and find a way to better understand why and how things happened.

What you are saying makes me think of Walid Raad’s practice. He’s made a lot of work about the Lebanese civil war and about the fact that some of the things that happened were so horrible, so traumatic, that they are ungraspable. For Raad it is impossible to coherently speak about the history of the civil war – facts can’t contain the experience of it.

I think this is a feeling that we all share. We express it differently. Walid has expressed it through creating fiction. Other artists have done it differently. But it is definitely a common feeling. It’s like you’re in pain, your body is in pain, but you just can’t find the right spot to heal it. So, every artist that has been interested in the civil war, its consequences, the collective memory, questions about identity, has been trying to find where the pain comes from. I don’t think we have the full answer yet.

Can you talk a bit about how the Arab Image Foundation started?

The foundation was founded in 1997 by three artists. It was Beirut after the civil war and there were a lot of initiatives taking place. A lot of people wanted to counter what happened during the war with culture. It was very much needed.

Those three artists worked with photography and were interested in the photographic collections that could have been lost, easily destroyed, or disappeared after the war. They realised that they needed to create an entity that could take care of this material. They started exploring different photographic practices not only in Lebanon, but also in the region to better understand the evolution of the medium in the region as well as the history. It was a mix of different ideas that bit by bit built up into what the foundation is today.

In 1997, members started joining the foundation, and they began travelling within the Arab region bringing collections back to Beirut based on their interests. In the first seven years, they brought 300 000 photographic objects. The foundation started being recognised and people started coming in with their own collections. So today we have 500 000 photographic objects divided into 305 collections. We keep the provenance of the collection as it is – we’re interested in the morphology and the structure of each collection, so sometimes the collection can be one single print, but it can go up to 50 000 negatives. We were interested in the memory of the collection as much as we are interested in the memory of the objects. We don’t restore, we don’t change things, we don’t even take off frames from the photographic objects that come in framed.

In the first couple of years they did what they could do – the people that worked at the foundation weren’t professionals in archival practices, and there were really none in the region. But they started learning, tried to collaborate with other institutions, and bit by bit the foundation grew to be actually a pioneer in archival practices. We were the first to create a cool storage room in the region in 2007. We also co-initiated and led a major project – MEPPI (Middle East Photograph Preservation Initiative), a collaboration between the Getty Conservation institute, University of Delaware, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art that helped train 92 professionals for 17 different countries on preservation and digitisation.

One of the major questions that we ask ourselves today is how to deal with such an archive? How do we deal with it responsibly and ethically? We hold 500 000 objects that are truth for many people. These are the memories, the histories, the representations of a lot of communities and a lot of diversity from the region. How do we deal with that responsibly?

In the beginning the organisation mostly focused on collecting and questions of preservation. Several exhibitions and publications were made, and this is what put the AIF on the international map. The first 10 years were the golden years of the foundation and then it ran into difficulties, especially when it came to raising money. The most difficult period was between 2014 and 2016, and then Clémence [Cottard Hachem], the co-director of the foundation, and I arrived. And since then we have been trying to re-shape things. The idea was to re-think our mission, set new objectives, think of our focus, and find a way to open up the AIF even more. We work today to push forward the engagement, reach out to the community, and find various ways for different kinds of people to interact with the archive.

How accessible is the archive for people who want to explore the collections and artists who might want to work with some of the material?

We’re eight people working at the foundation, so we lack human resources. Nevertheless, we decided to open up our doors again with limited times and today the foundation is open two days per week. During those two days, the public is welcomed. We give access to a resource library with 2400 publications dedicated to photography, archival practices, and research books from the region; our contact prints – all the negatives that are part of the collection have been hand printed, we have a 175 000 contact prints, which are a great entry to the collections; – as well as our old data base where we have 35 000 digitised images.

We also have two stations where researchers and artists can work. We have people who can help them out with their research. And whenever we are there, we try to communicate with them more about their research, try to help them out, put them in contact with whoever brought the collection, who owns it or is part of it. Our collections have not been documented fully – that has been a big task as well. Sometimes a collection is very well documented and you have tons of information related to it, but other times we only have basic documentation. Whenever we find interest in a specific collection, we try to develop our knowledge about it, and bring in information as much as we can.

Pretty soon we are going to have opportunities for residencies. For the time being we have received artists who have come to work in the foundation but they have funded their own residency.

Do you also allow artists to use the material within their work?

Yes. This was one of the many important things, that gave the foundation its own identity. We work at the intersection of archival practices and contemporary art. Our aim is to link the archive to contemporary discourses and narratives.

Our contract clearly states that all artists or researchers can use the images from the archive in their own work as long as they acknowledge clearly that either it is a fictional context or whatever is being made is not damaging to the people, the photographer, the owners of the collection. We try to follow up on the artwork that is being produced. We cannot control everything – people have downloaded low resolution images and used them. Recently we ran into this problem – people used images from the AIF to promote homophobic ideas. They posted images from a collection on Instagram, where there is no need for high resolution files, and they weren’t interested in the copyrights at all. They used the images in a way where they totally separated them from their real context and started spreading ideas around them.

Can you talk a bit more about the residency and educational program you are starting?

Our focus in the next three years is based on three main acts: accessibility, activation and education. Accessibility means that we’re working on our digitisation plan, everything is going to be on the platform we launched two months ago. It’s still in the beta version, so there are a lot of bugs, but the idea is to launch also an interactive/lab section, where we would invite people for online residencies, and they could show their own projects.

Activation is how we’re going to push the material that we have towards artists and cultural practitioners. This is to think of new ways to present it to the public, extract new ideas from the collections, new thoughts, new readings. To be able to activate the collection we need to create opportunities. For us that is linked to residencies, exhibitions, commissioning artists to produce works, publications, working with artists, writers, critics, with journalists, organising conferences, talks, possibilities to hold seminars and workshops in universities. All of this is in preparation right now. It requires funds which is something we’ve been working on and hopefully we will get there.

The idea is to organise residencies in Beirut and outside of Beirut to de-centralise a bit. Give the possibility for artists to come and work with the archive. We’re not always concerned with the outcome but are interested in the thought process – how artists can look, think, and interact differently with the collections.

Our educational program aims to give access to courses inexistent in Lebanon but also create a true community around photography and the archive on the local and regional level. It will enhance the capacities and know-how of interested parties and give better chances to students and professionals in the job market. It will open up new horizons. I am not able to delve into details, but we will announce the program and all its components very soon.

You took over the organisation together with Clémence in 2016. How did that happen?

The foundation was going through a difficult phase. The governance of it is very simple. We have members and out of these members a board of directors is elected. The board of directors then hires a director. In 2016 the opportunity for directorship opened up.

I used to be the director of a contemporary art gallery based in Beirut, which focused a lot on photography. I developed a huge interest in contemporary photography. Clémence is a specialist in 19th century photography, and she worked with a private collection in Lebanon. She also worked with different institutions in France before she came to Beirut. When the AIF wanted to hire a director, we decided to propose a co-directorship. I believe that the work the AIF does necessitates two people. Clémence is heading the collection and the conservation activities. I am handling the administrative aspect that is crucial for the survival of the foundation, and we both think of its artistic and contemporary activities.

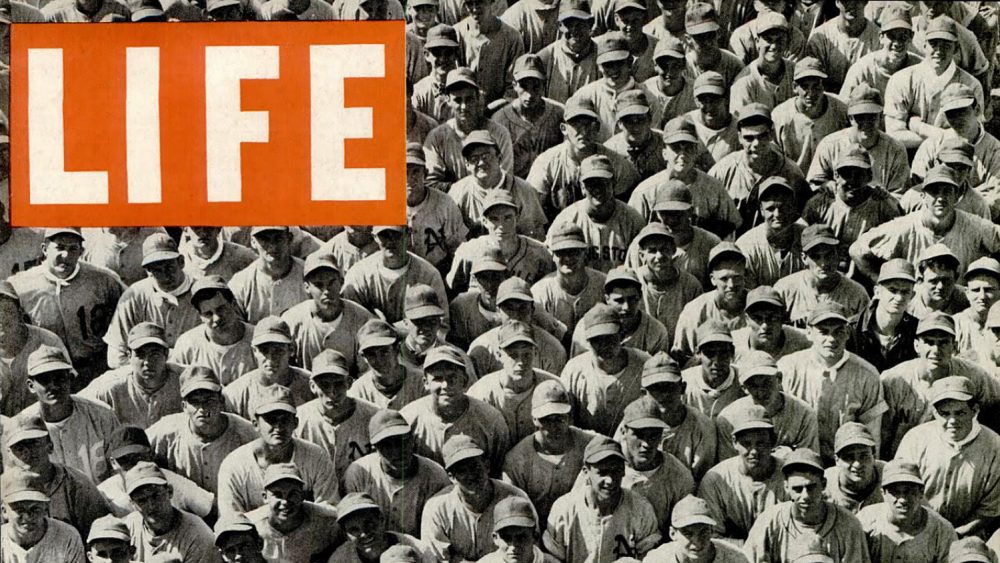

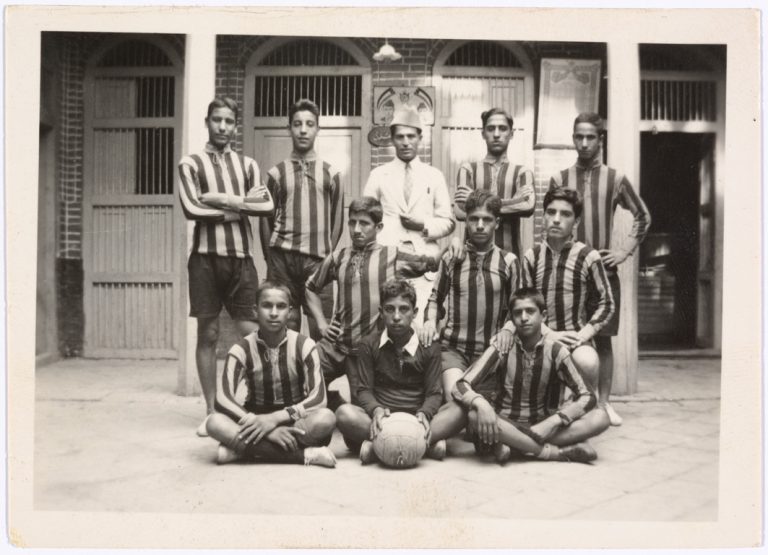

During your ISSP talk you showed an image of an Iraqi volleyball team that AI had interpreted as a military photograph. This is a good example of how biased algorithms are. As you spoke about the foundation holding different truths about how things are and have been, in what ways do you think we can fight against really stereotyped readings of imagery?

I think it starts with very small things. We can instigate change. The exhibition we did in Arles is supposed to plant seeds in people’s minds. We wanted to confront the public with a certain reality on the way we look at images, how we see things based on what is being given to us and how our heads are programmed. In the end, we see daily a lot of images, we’re bombarded with visuals, and we just can’t digest it anymore.

At the foundation, we ask ourselves the tough questions. We started reviewing the ways we should tag, what should we take in consideration, how the communities are being represented, what are the words that we can use today, what are the words that we shouldn’t use, how open should we be or how conservative, should we have a political position or not, should we have a specific way of presenting things or not, should we keep things subjective or objective?

These are questions that came to us when we started dealing with tagging. Should we use AI or not? Will this lead us to stereotypical tagging? While, in terms of time, it does facilitate a lot. If you see an image of this landscape, you wouldn’t want to just type in: “tree”, “cabana”, “palace”. This is something that the AI software can do really quickly. The problem arises whenever you talk about identities. It’s not about things that you see, but what is behind.

What we’re trying to do with the platform, is crowdsource the documentation of our objects while giving the chance to the public to interact directly with those images. We want them to engage in the mission of the foundation, understand that the collections represent them and that they are also responsible for transferring their knowledge to the future generations.

There has been a lot of interest in archives within the art world in the last couple of years. How has that influenced the way that the foundation works?

I’d like to think that the foundation set that pace a long time ago. 22 years ago, when it started, all of it was very instinctive, very intuitive, and I think that the people who founded and worked at the foundation were brilliant in the way they shaped the organisation and how it has been transformed today.

But there’s definitely a hype around the archive now. I think that people want to understand things differently. Through archives today, we can raise questions, and then try to find answers. Sometimes we will and sometimes we won’t, but the idea is to always try, to think of things differently, and use the objects of an archive as a tool to a better understanding.

How do you see the role of the AIF in the context of the Beirut and Lebanese art scene?

I believe the foundation received international recognition rather quickly from its beginning. On a local level, the foundation is very well known within the cultural sphere yet the broader public has yet to discover who we are. While the foundation’s activities and practice deal with elements of cultural heritage that spans across the region, we are a private non-profit organisation with a public vocation. We need to continue producing knowledge, preserving histories and building the archive of the future.